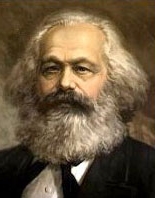

Karl Marx

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 15 min

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 15 min

| Join the party! Communism |

| Opiates for the masses |

| From each |

| To each |

“”The world would not be in such a snarl had Marx been Groucho instead of Karl.

|

| —Irving Berlin |

“”The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.

|

| —Karl Marx |

Karl Marx[note 1] (1818–1883) was the godfather of all pinko commie scum; he co-wrote the Communist Manifesto (with Friedrich Engels) and wrote Das Kapital. He was a German born philosopher, economist, political activist, and writer, and is considered the grandfather of sociology and political economy.

His ghost subjects Ayn Rand's to eternal wage slavery as she burns in hell.[citation NOT needed]

Life[edit]

Marx was born in 1818 in Prussia to a middle-class family. After he finished university, he worked as a journalist. In the 1840s, he met Friedrich Engels in France, which led to a lifelong friendship between the two. He co-authored The Communist Manifesto with Engels and the two collaborated often. He married Jenny von Westphalen and had six children. He lived and worked Paris, Cologne, and Brussels, before settling in London. Later in life, Engels supported Marx's work through his health issues and financial troubles. Marx was working on a sort of magnum opus, Das Kapital, subtitled "A Critique of Political Economy", a several-volume treatise on the economics of capitalism. He was only able to publish the first two volumes in his lifetime. Marx died in 1883 in London.

Ancestry[edit]

Marx was of Jewish descent, which was the original prompt by conspiracy theorists to tie Marxism in with the theory of the international Jewish conspiracy, claiming that communism was made to advance Jewish domination of the world (oddly, those clever Joos failed to foresee this and perhaps use a non-Joo to publicly expound upon their great conspiracy). However, Marx's relationship with his Jewish identity is a great deal more complex than all that. His father, Herschel Mordechai, came from a long line of rabbis but received a secular German education himself and converted to Lutheranism around the time of Marx's birth, changing his name to Heinrich Marx. This was a career move; Herschel was a lawyer, but the German government had made it illegal for Jews to practice law. Karl Marx was baptized into the Lutheran church at age six and grew up to be a well-known atheist. Later in life he wrote an essay, On the Jewish Question, in which he drew on stereotypes of money-worshiping "huckster" Jews and stated that as a part of the development of capitalism, "Christians [had] become Jews" (i.e., the "Jewish" culture of capitalism had assimilated all the old cultures of Europe), and there is considerable debate about how serious that essay is about all that.

Thought[edit]

Marx's body of work is highly nuanced and highly discussed, with many differing opinions, from opponents and Marxists alike, coming to different conclusions on his work. As such, it can be difficult to summarize Marx's thought without stepping on any toes. These incredibly basic tenets, however, are almost universally agreed upon:

- A materialist view of the world; that history and thus society is formed by material, physical realities, such as nature, labor, and technology, and that things like ideology and religion, are a "superstructure" shaped by material conditions. This is often called "historical materialism"

- A dialectic model of history – directly influenced by Hegelian dialectics – where society progressively evolves and changes over the course of human history based on material conditions, and that "the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles"

- Classes act primarily to serve their own economic and material interests

- Under capitalism, the working class is exploited by the ruling class through the extraction of surplus value (the profit that goes unpaid to workers)

- Capitalism, as the successor of feudalism, was/is unstable and would/will be revolted against due to the intrinsic contradiction between the bourgeoisie (the capitalist class) who own the means of production and the proletariat (the working class) who work the means of production – "means of production" are assets, like land, machinery, or capital, that are used to make products[note 2]

- The revolt against the bourgeoisie by the proletariat should/will take control of the means of production and establish socialism, where the workers control the means of production

- Communism, the eventual, final form of society, will come after socialism, and it will be classless, currency-less, and stateless

Again, this barely scratches the surface, but these general beliefs serve as the foundation of a great deal of Marx's thought. Marx has received a great deal of attention in both academia and public discourse, more than his collaborator Engels, by a wide range of audiences, and his work has been interpreted and utilized in different fields. Political theorists, philosophers, social scientists, economists, activists, post-colonial scholars, feminists, and even literary theorists all take different things away from Marx and talk about his work in different ways.

Religion[edit]

Karl Marx was famous as an atheist, coining the phrase "opium of the masses" in Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right:

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.

Criticism has plucked the imaginary flowers on the chain not in order that man shall continue to bear that chain without fantasy or consolation, but so that he shall throw off the chain and pluck the living flower. The criticism of religion disillusions man, so that he will think, act, and fashion his reality like a man who has discarded his illusions and regained his senses, so that he will move around himself as his own true Sun. Religion is only the illusory Sun which revolves around man as long as he does not revolve around himself.[3]

More than just an atheist, this passage shows that Marx had in fact an anti-theist bent, believing that the emancipation of the people was furthered by the critique of religion, and perhaps even its abolition. This anti-theism was taken up by Lenin and Stalin and enforced; as such, Marx and communism are often associated, in the reactionary worldview, with a tyrannical, godless despotism.

Darwin and Marx[edit]

Karl Marx was deeply interested in the work of his contemporary Charles Darwin. He was an admirer of Darwin and sent copies of Das Kapital, in which he was cited, to him. (Darwin never read it.)[4] Indeed, despite their differences, both theories can be seen as rejections of essentialism, just applied to very different fields. Marx saw Darwin's theory of evolution as a signal that his theories were headed in the right direction: that humankind is the product of historical changes. He wrote in a letter to Ferdinand Lasalle![]() :

:

Darwin's book is very important and serves me as a basis in natural science for the class struggle in history. One has to put up with the crude English method of development, of course. Despite all deficiencies, not only is the death-blow dealt here for the first time to "teleology" in the natural sciences but their rational meaning is empirically explained.[5]

Marx was not uncritical of Darwin, however, and took many issues with his arguments. The notion that Marx and Engels were attempting to co-opt Darwinian evolution for their own political project does not reflect how they related to the theory. Still, at Marx's graveside, Engels remarked, “Just as Darwin discovered the law of development of organic nature, so Marx discovered the law of development of human history.”[6]

Misconceptions[edit]

Marx and Engels did not invent the idea of socialism or even communism. There were communist and socialist trade unions and political parties prior to the pair publishing anything on political economy. Small-scale communes are so old that there is a rather well-known one in the New Testament.[7] Additionally, Marx and Engels didn't invent philosophical theorizing about socialism, either. There were plenty of contemporary thinkers on the topic who published just as many books as Marx and Engels and with whom Marx debated publicly. Contrary to popular belief, Marx did not create the phrase "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need"; he merely popularized the phrase, which was said to have been originated by Étienne-Gabriel Morelly![]() in his 1755 book, Code de la nature, ou de véritable esprit de ses lois.

in his 1755 book, Code de la nature, ou de véritable esprit de ses lois.

Marx was a theory-guy who had little regard for concrete political suggestions. One exception being a single chapter of the Communist Manifesto, where he and Friedrich Engels suggest that advanced countries abolish all private land ownership, implement a progressive tax, do away with inheritance, implement free education, confiscate the property of emigrants and anti-communist rebels, implement heavy state centralization, and make everyone legally responsible to work.[8] Though he went through a somewhat authoritarian phase in the middle of his life, Marx's work did not advocate anything remotely approaching the authoritarianism advocated and then carried out by Stalin or by Mao. As Marx grew older, he returned to the more libertarian (no, not that kind of libertarian) tendencies of his youth.

Marx's bigotry[edit]

Those who read Marx in depth will notice the repeated and sometimes extreme prejudice involved in his insults and general opinions. Many modern Marxists try to deny his racism. It should, of course, be remembered that everyone is a product of their time. After all, Marx's philosophy emphasizes the influence of material and historical conditions influencing people's lives, and the man himself was no exception. Marx exposed deep prejudices in both personal letters and in his published writing. He expressed numerous horrendous comments on Slavs, ‘Negroes’, Bedouins, Jews, Chinese and many others.[9] At the same time, these prejudices are often used by bad faith critics to dismiss all of Marx's work without actually engaging with it at all.

One of the most controversial of his bigotries was Marx’s antisemitism. Despite his Jewish heritage, Marx didn’t identify as a Jew and wasn’t raised as one. He went on to write disdainful comments on Jews throughout his career. "On the Jewish Question",[10] in which he argues against Bruno Bauer that a secular state would not emancipate people from their material conditions, is often considered his most antisemitic work. In it, he makes statements that describe Jews as money-grubbing hucksters, and how these ascribed temperaments relate to capitalism. Some scholars claim Marx was not antisemitic, and that he was being sarcastic, or that he wasn’t that bad. Others claim that this allegation comes from an anachronistic or superficial reading of "On the Jewish Question".[11] More antisemitism can be found in further writings and correspondences. He described Jews as greedy and once referred to them as “leper people.”[12]

Like virtually all Europeans of his era, Marx viewed those of African ancestry as more primitive than most other races.[13] For example, he said Black people were “a degree nearer to the rest of the animal kingdom than the rest of us”[14][15] and he referred to people with racial epithets.[16] Despite his racism, Marx was in favor of the abolition of slavery.

Marx wrote that he distrusted Russians and generally disdained Eastern Europeans.[17][18][19] Marx was also sort of pro-imperialism, seeing it as a natural and necessary stage in the evolution of world political economy. He wrote that he felt England had a duty to annihilate “old Asiatic society” in India.[20] When it comes to Chinese people, Marx criticized them, claiming that "It would seem as though history had first to make this whole people drunk before it could rouse them out of their hereditary stupidity".[21]

Influence and legacy[edit]

Despite his reputation in certain circles, Marx is perhaps the most influential economist of the 19th century. Not because of his impact on economics as a study, where his reputation is largely relegated to the heterodox Marxian school, but because of his political impact in the development of the communist bloc in the 20th century. Economists Magness and Makovi argued that the 1917 Russian Revolution - which transpired several decades after Marx's death - is responsible for elevating Marx’s fame and intellectual following above his contemporaries.[22]

Marx wrote for the New York Daily Tribune, and some believe Abraham Lincoln regularly read his columns,[23] given the language with which the president spoke about the changes then taking place in the American and world economies that he and the radical Republicans were dreading. Marx did, in fact, praise Lincoln for issuing the Emancipation Proclamation and congratulate him on his 1864 reelection and was probably entirely sincere while doing so, which should come as no surprise as Marx regarded wage-earning proletarians as still better off than slaves.

Marx and communist states[edit]

His fanboys have shown quite a tenacious resistance to the suggestion that something might be wrong with what he said (though given the large split between different factions, to the point where in the Spanish Civil War, Stalinists mostly killed Trotskyists, it is understandable), even as leaders professing his philosophy turn into dictators one after another, and the combined death toll from their regimes rises into the mid-to-high eight figures (largely attributed to Stalinist Russia and Maoist China).[note 3] One common response to this is to point out that certain anti-communists also racked up non-negligible skull counts in the name of fighting communism, notably Adolf Hitler (and his Axis allies such as Mussolini, Franco, and Pavelic), Suharto of Indonesia, Syngman Rhee of South Korea,[note 4], Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam, a succession of military dictators in Guatemala, the junta in El Salvador, the Somozas in Nicaragua, Augusto Pinochet of Chile, Jorge Rafael Videla of Argentina, Hissene Habre in Chad, François Duvalier![]() of Haiti, and Rafael Trujillo

of Haiti, and Rafael Trujillo![]() of the Dominican Republic, many of whom were backed by the United States throughout the Cold War. This is an instance of tu quoque,[note 5] although certain US politicians such as Jeane Kirkpatrick backed anti-communist regimes solely on the basis that they were not as bad as communist regimes, which is debatable as many anti-communist regimes killed an equal or higher per-capita number of those under their control.[note 6]

of the Dominican Republic, many of whom were backed by the United States throughout the Cold War. This is an instance of tu quoque,[note 5] although certain US politicians such as Jeane Kirkpatrick backed anti-communist regimes solely on the basis that they were not as bad as communist regimes, which is debatable as many anti-communist regimes killed an equal or higher per-capita number of those under their control.[note 6]

However, it is also worth noting that none of Marx's predicted "proletarian revolutions" occurred in industrialized nation-states, such as the United Kingdom[note 7] where he lived but, instead, in less-industrialized states such as Russia and China during periods of political and economic turmoil. Marx had written that industrial capitalism was a necessary precondition for communism. Marxist rhetoric is also appealing to post-colonial independence movements, even those which are largely agrarian and lacked an established working class. In some cases, such as Yugoslavia, Vietnam, and China, the communist revolutions had popular local support due to the roles they played in war; while in other cases, such as Eastern Europe and Afghanistan, communist governments were largely forced upon them, and such countries essentially functioned as puppet states of the Soviet Union. Of course, forcing a political regime on a largely-unwilling populace does not tend to engender much love and might end a tad bloody. It is also a fact of history that any government will overstay its welcome. If it is the government of a democratic state it will be voted out, except when it's not.![]() If not, too bad.[note 8]

If not, too bad.[note 8]

A frequent argument by Marxists[edit]

To get this out of the way, prior to the Russian Revolution (and again after 1991) most Marxists interpreted Marx differently from Lenin. While the non-Leninist interpretation says, basically, that full industrial development under a capitalist system is a precondition for communism (which would make the USSR not a communist state, at least not in Lenin's time), Lenin argued that given the right revolutionary leader (such as himself), a largely-agrarian state (such as Russia) could "skip" capitalism and become communist immediately. Thus, many modern Marxists have explained away the fall and the atrocities of Maoist China (which is now communist in name only) and the USSR as a consequence of their having been largely agrarian at the time of revolution, and hence not "really" communist. Whether this constitutes a no true Scotsman depends largely on your own views on capitalism, communism, and the various Leninist dictatorships.

Marx vs. Marxists[edit]

Whatever you may think of Marx and his fanclub, he did at the very least condemn the fanaticism when he witnessed it. A rather famous quote of Karl Marx reads:[25]

"What is certain is that I myself am not a Marxist." (Originally in French: Ce qu'il y a de certain c'est que moi, je ne suis pas Marxiste.)

He said this in reaction to Jules Guesde, a leader of French workers and vanguard of French Marxism, who visited Marx in London 1880. They had a disagreement about the political programme written for the Parti Ouvrier (Labour Party), in what seems to be the case in which Marx was in favor of pragmatic achievements within capitalism while his cult didn't want any reasonable concessions but just concern-troll the opposition (Marx called it "revolutionary phrase-mongering").[note 9]

Marx's influence today[edit]

The good[edit]

- Support for and instances of worker self-management are growing throughout the world. A number of Western and Latin American countries have adopted policies aimed to produce and support employee-owned firms. Other countries, such as Great Britain and Spain, are simply waiting to elect their left-wing parties to a majority in their parliament before doing so. Bernie Sanders included the idea on his platform,[26] but never brought it up during his campaign; he also never became POTUS, the poor bastard.

- The spread of reformist socialist ideologies like Social Democracy has rendered his central thesis—the only way to improve lives for the bottom half of society is armed revolution[citation needed]— less relevant in the modern day, though many would say that is a bad thing rather than a good one[citation needed].

- The threat of Marxist revolution scared a lot of governments into making positive reforms for the working class. People in power generally don't make concessions to people without power out of the goodness of their hearts...[citation needed]

The neutral[edit]

- Marx is still taught and studied in academia, and his influence is still felt in the study of sociology, political science, philosophy, and more.

- Marx's political theories have become increasingly popular with Millennials and Gen Z.[27]

The bad[edit]

- A hefty amount of strongmen from the "somewhat tolerable if you're desperate" to the "unfathomably horriffic" have justified their abuses by referring to his work. It happens too often when Marx-derived ideologies are implemented to be a regrettable coincidence.

- The spread of reformist socialist ideologies like Social Democracy has rendered his central thesis—the only way to improve lives for the bottom half of society is armed revolution[citation needed]— less relevant in the modern day, though many would say that is a good thing rather than a bad one[citation needed].

- Tankies still exist on the fringes of society in the present day.

See also[edit]

- Communism

- Socialism

- Das Kapital

- Communist Manifesto

- Conflict theory

- Social democracy - which is accused of being "communism" when it is clearly not socialist (it is a mixed market economy)

- Charles Fourier - an earlier socialist thinker

- Frankfurt School - a school of mid-20th Century philosophers influenced by Marx

External links[edit]

- Works of Karl Marx in German and English on Wikisource

- Marx and Engels' works at the Marxists Internet Archive (incomplete but extensive)

- Song about Karl Marx. from Histeria!

- Karl Marx in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Notes[edit]

- ↑ The name "Karl Heinrich Marx", used in various lexicons, is based on an error. His birth certificate says "Carl Marx", and elsewhere "Karl Marx" is used. "K. H. Marx" is used only in his poetry collections and the transcript of his dissertation; because Marx wanted to honor his father, who had died in 1838, he called himself "Karl Heinrich" in three documents. The article by Friedrich Engels "Marx, Karl Heinrich" in Handwörterbuch der Staatswissenschaften (Jena, 1892, column 1130 to 1133 see Marx/Engels Collected Works

Volume 22, pp. 337–345) does not justify assigning Marx a middle name. See Heinz Monz: Karl Marx. Grundlagen zu Leben und Werk. NCO-Verlag, Trier 1973, p. 214 and 354, respectively.

Volume 22, pp. 337–345) does not justify assigning Marx a middle name. See Heinz Monz: Karl Marx. Grundlagen zu Leben und Werk. NCO-Verlag, Trier 1973, p. 214 and 354, respectively.

- ↑ While capitalism has evolved, many of the same exploitative relationships still remain intact. The less sanitary elements just more often get exported to the Global South (think "cheap labor," that's because these countries have weak protections for labor) or are shoved out of sight. The American agriculture industry heavily uses undocumented immigrants as a source of labor,[1] but don't have the same protections (however nominal) legal American laborers do.[2]

- ↑ The number of deaths varies depending on whether famine deaths are included in the total. High-end estimates for the number of victims under Mao in the PRC include some 20,000,000 to 72,000,000 victims of the famine caused by the "Great Leap Forward", which stemmed from a bungled attempt to strengthen China's economy. If the criteria was narrowed to include only deliberate political murders and deaths in labor camps, the number would probably be in the millions-to-low tens of millions. Among Mao's atrocities were the mass killings of "counterrevolutionaries" and landlords during the early 1950s (2-5 million dead) and an estimated 400,000 to 3,000,000 killed between 1966 and 1976 in the "Cultural Revolution".

- ↑ During the Korean War, impoverished farmers were liquidated because they "might" have become communists in the future. Douglas MacArthur considered the matter to be an internal affair of America's anti-communist allies

- ↑ Unless, maybe, you also consider some argument about the supposed "moral superiority" of anti-communist regimes. But even that argument is debatable.

- ↑ 42,171 extrajudicial killings by security forces were recorded in El Salvador between 1978 and 1983, comprising nearly 1.0% of the population. A similar proportion was killed in Guatemala. These numbers may be a gross underestimate as many killings were unrecorded. In Timor-Leste, as much as 44% of the population may have perished due to the Indonesian Army's policy of massacres and enforced famine, a scale which is equal to or greater than Pol Pot's reign in Cambodia.

- ↑ Unless one counts the Paris Commune

of 1871, which was crushed by the reactionaries in less than two months, or the Spanish Revolution

of 1871, which was crushed by the reactionaries in less than two months, or the Spanish Revolution of the Spanish Civil War, which was ironically crushed by so-called communists, or the Hungarian Revolution

of the Spanish Civil War, which was ironically crushed by so-called communists, or the Hungarian Revolution , which was again crushed by the so-called communists, or the revolution Rosa Luxemburg led in Germany, which was crushed by a social-democratic regime

, which was again crushed by the so-called communists, or the revolution Rosa Luxemburg led in Germany, which was crushed by a social-democratic regime

- ↑ Danish historian Erling Bjøl deserves a quote here, speaking about Walter Ulbricht's durability as the leader of communist East Germany: „Ulbricht had Stalin's confidence. He turned the SED into a reliable instrument of power and disproved the old adage, that bayonets can be used for everything, except sitting on them.“

- ↑ Would Marx oppose Bernie-or-Bust? A mystery for the ages.

References[edit]

- ↑ Wisconsin’s Dairy Industry Relies on Undocumented Immigrants, but the State Won’t Let Them Legally Drive[a w], ProPublica

- ↑ They Got Hurt At Work — Then They Got Deported[a w], NPR

- ↑ Marx, Karl. "Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right". Marxist Internet Archive.

- ↑ https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/en/science/leading-figures/two-clashing-giants-marxism-and-darwinism/

- ↑ Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Marx-Engels Collected Works, Volume 40

- ↑ https://isreview.org/issue/65/marx-and-engelsand-darwin/index.html

- ↑ See Acts 4:32-35 and Acts 2:44-45.

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch02.htm

- ↑ van Ree, Erik (2019-01-02). "Marx and Engels’s theory of history: making sense of the race factor". Journal of Political Ideologies 24 (1): 54–73. doi

:10.1080/13569317.2019.1548094. ISSN 1356-9317.

:10.1080/13569317.2019.1548094. ISSN 1356-9317.

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/jewish-question/

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on On the Jewish Question.

- ↑ https://www.jewishpress.com/sections/features/features-on-jewish-world/karl-marx-a-self-hating-jew/2019/05/08/

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271216034_In_the_Interests_of_Civilization_Marxist_Views_of_Race_and_Culture_in_the_Nineteenth_Century

- ↑ https://www.newsherald.com/story/opinion/2020/08/16/many-marxists-dont-realize-their-hero-racist-and-anti-semite/3369024001/

- ↑ https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13569317.2019.1548094

- ↑ http://hiaw.org/defcon6/works/1862/letters/62_07_30a.html

- ↑ https://books.google.ch/books?id=FH-LCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT208&lpg=PT208&dq=I+do+not+trust+any+Russian.+As+soon+as+a+Russian+worms+his+way+in,+all+hell+breaks+loose.&source=bl&ots=mR1RfXqLqs&sig=ACfU3U1FGNu-dhds0z-NW75raMtyITBiAw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjeqs7zpf_qAhXGThUIHRZ4A6oQ6AEwAXoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=I%20do%20not%20trust%20any%20Russian.%20As%20soon%20as%20a%20Russian%20worms%20his%20way%20in%2C%20all%20hell%20breaks%20loose.&f=false

- ↑ https://www.international-communist-party.org/English/Texts/53FaRNen.htm

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/subject/russia/crimean-war.htm

- ↑ https://marxists.catbull.com/archive/marx/works/1853/07/22.htm

- ↑ "Karl Marx in New York Daily Tribune".

- ↑ Magness, Phil; Makovi, Michael (2022-11-09). "The Mainstreaming of Marx: Measuring the Effect of the Russian Revolution on Karl Marx’s Influence". Journal of Political Economy. doi

:10.1086/722933. ISSN 0022-3808.

:10.1086/722933. ISSN 0022-3808.

- ↑ Brockell, Gillian. You know who was into Karl Marx? No, not AOC. Abraham Lincoln. The Washington Post. July 27, 2019.

- ↑ https://www.focus.de/politik/deutschland/nach-protesten-in-den-usa-statuen-von-bismarck-oder-marx-wegen-rassismus-vorwuerfen-abbauen-so-denken-die-buerger_id_12111877.html

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/05/parti-ouvrier.htm#n5

- ↑ https://ourfuture.org/20150817/bernie-sanders-proposes-to-boost-worker-ownership-of-companies

- ↑ Jones, Owen. Eat the rich! Why millennials and generation Z have turned their backs on capitalism. The Guardian. September 20, 2021.

KSF

KSF