Mali

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 9 min

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 9 min

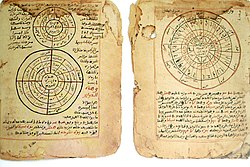

“”At its zenith in the middle of the 15th Century Timbuktu was known all over the world as a repository for all sorts of knowledge, including Arabic Islamic writing, science, maths and history. What is so important about Timbuktu's literary patrimony is that it is a challenge to Western ideas that Africa is a land of song and dance and oral tradition. It reveals a continent with an immensely rich literary and scientific heritage.

|

| —Lydia Syson, British historian of Africa.[1] |

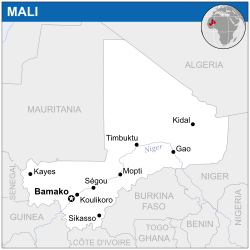

The Republic of Mali is a landlocked state in Saharan Africa. Its capital is Bamako, and the country's northern borders reach deep into the interior of the Sahara Desert. Its southern regions host most of the country's population, clustered around the Niger and Senegal rivers. The vast majority of its population follows Islam.

Mali was home to three powerful empires that controlled the lucrative trans-Saharan trade routes. The largest of these empires was Mali, where present-day Mali takes its name. The name "Mali" means "place where the king lives".[2] As the hub of the trans-Saharan trade, Mali became a rich center of science, mathematics, architecture, literature, and art.[3][4] This activity was mainly concentrated in the famous city of Timbuktu.

During the Scramble for Africa, France seized control of Mali and incorporated it into the French colonial empire. Mali regained its independence in 1960, becoming a dictatorship until a 1991 military coup led to the establishment of Mali's current dysfunctional democracy. In January 2012, Tuareg tribal peoples rebelled in northern Mali, trying to secede and establish an independent state. Around the same time, another coup took place, complicating and exacerbating the civil war. In 2013, France decided to give that "African adventurism" another try and launched a counter-terrorism operation to root out the Tuaregs. The operation succeeded in retaking most of northern Mali and restoring Mali's legitimate government.

Mali still struggles with terrorism and ethnic violence. During the Tuareg conflicts, many Malians fled the country and have stayed abroad in places like Mauritania, Niger, and Burkina Faso.[5] Mali is still in the bottom 25 poorest countries globally, and its economy is mainly dependent on gold mining and cotton exports.

The United States State Department currently maintains a Level 4 travel advisory against Mali, citing the extreme risk of violent crime and terrorism and warning that US government employees are restricted from entering northern Mali due to safety concerns.[6]

Historical overview[edit]

Imperial age[edit]

Mali was once part of three powerful West African empires which drew their power and wealth from lucrative trans-Saharan trade in gold, salt, slaves, and other precious commodities. The earliest of these empires was Ghana, which rose in the Sixth Century CE. Ghana had nothing to do with the modern state of Ghana; its territory actually overlapped far more with the modern state of Guinea. If that's confusing to you, blame colonialism.

Ghana benefited because its lands had abundant gold, copper, ivory, and easy access to the major Niger and Senegal rivers.[7] During this time, Islam began to spread throughout Ghana's lands, introduced by Muslim merchants traveling from North Africa. The empire stockpiled vast amounts of wealth, becoming known across Africa and even Europe as a land of fabulous wealth. Eventually, however, the empire collapsed following droughts and civil wars.[7] So it goes. The empire lasted until the Twelfth Century.

Legendary figure Sundiata Keita, prince of the Malinke tribe, went on a series of conquests in the mid-1200s to reunite the shattered lands of the old Ghana Empire.[8] He established his capital in the city of Niani, took the title Mansa, and became the founder of the Mali Empire. Although this historical figure likely existed, African oral traditions have transformed him from a historical conqueror into a mythic warrior-magician figure.[8] Notably, contemporary Islamic scholars disagreed with the oral traditions over whether Sundiata himself converted to Islam or not.

Regardless, Mali gradually converted to Islam, playing a major role in spreading the religion across western Africa. One of the empire's most important trade centers was Timbuktu, becoming home of the "great mosque", also known as Djinguereber or Jingereber, designed by the famous architect Ishak al-Tuedjin, who had been enticed to move to Mali from Cairo, Egypt.[9] Trade caused the city to explode in size, as warehouses needed to be built to store goods and inns had to be built to house weary merchants. Mansa Musa I famously went on a hajj to Mecca around 1324 CE, traveling with a huge entourage and throwing around so much gold that he crashed the markets across Egypt for twelve years.[10] Arab historian Al-Makrizi wrote about the king's visit to Cairo, describing Musa as "a young man with a brown skin, a pleasant face and good figure... His gifts amazed the eye with their beauty and splendour."[10] Musa then brought home many Arab architects, artists, and scholars.

Due to civil wars and disasters, the Mali Empire eventually collapsed around the mid-Seventeenth Century. They were replaced by the ascendant Songhai Empire, which began to struggle due to competition from European traders using sea lanes to transport goods from the east to the Mediterranean rather than using the Sahara's trade routes.[11] This empire also crumbled from within, and much of its northern territory was subsequently conquered by Morocco.

This marked the end of Mali's imperial period.

French colonial rule[edit]

After Mali's great empires fell, the region stagnated for a while. Rival warring states kept ransacking each other, and these wars and the resulting refugee exoduses meant that agriculture and production declined for centuries.[12]

French military invasions of the Soudan (France's name for the area) began around 1880, and France started making a serious effort to occupy the continental interior around 1890.[13] The French were motivated by the wave of colonial competition called the Scramble for Africa. France seized most of Mali's great cities by the end of the century—Timbuktu in 1894 and Gao in 1898.[12]

Malians were required to produce raw materials for France, especially cotton and peanuts. The French built infrastructure to transport these goods to the coastline of Africa, but they made no effort at all to develop Mali beyond this.[12] Indeed, the French did all they could to prevent Mali's development, fearing that the Malian people would potentially cast off French rule. That's why communication and education were kept to the bare minimum. However, in the 1930s, to build up the local cotton industry to feed French textiles, France established an irrigation program that flooded areas (thereby displacing Malian villages) of the Niger River Valley, using a labor regime that amounted to plantation slavery.[14]

The French justified their actions with typical colonialist language. French statesman Jules Ferry spoke for many when he proudly proclaimed: "The higher races have a right over the lower races, they have a duty to civilize the inferior races."[14] Despite their brutal rule, the French still had the gall to recruit Malians into fighting their wars. About 10,000 Malians died in the trenches of World War I, fighting in a conflict that had nothing to do with their interests.[14] Malians also participated in World War II. Once again, they did not understand why. Says Baby Sy, a veteran from Burkina Faso, "People didn't understand when they heard talk of fascism. We were just told that the Germans had attacked us and considered us Africans to be apes. As soldiers we could prove that we were human beings. That was it. That was all the political explanation there was at the time."[15]

Post-independence[edit]

Mali agreed to the new French Loi Cadre in 1956, which granted the colony more power over its internal affairs.[12] Mali then became independent in 1960.

President Modibo Keita, Mali's new leader, immediately transformed the country into a single-party socialist state and aligned with the Eastern Bloc.[12] This was relatively short-lived, as a military coup led by Moussa Traoré turned Mali away from party dictatorship and toward a military dictatorship. Yippee! The junta's attempts at economic reform failed, and their promises to establish a civilian government went unfulfilled. Despite facing harsh government crackdowns, student unrest in the 1980s and 1990 managed to succeed in forcing the government to adopt democratic reforms.[12] A group of 17 military officers arrested Mali's dictator in 1991 and then created the Transitional Committee for the Salvation of the People. This story ended happily, as the provisional government handed power off to civilian authorities, who then held elections. Mali's current constitution was approved by referendum in 1992.[12]

2012 war[edit]

In 2012, separatists and Islamists from the long-marginalized Tuareg ethnic group declared an independent state, Azawad, covering the vast desert in northern Mali. No legitimate country has recognized this breakaway state. The Tuareg began their rebellion because Mali's borders were drawn by the French, who had French colonial interests and not the interests of the region's people in mind. The Tuareg had engaged in several failed rebellions before 2012 but that year proved to be their golden opportunity, mainly due to the instability in Libya. During the Arab Spring and the Libyan Civil War, Tuareg mercenaries came across the Sahara to fight against Muammar Gaddafi. While there, they gained weapons and battlefield experience and picked up some new allies, including Jihadi groups Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and Ansar Dine, which were also fighting to topple Gaddafi. After Gaddafi was toppled, foreign fighters were no longer welcome in Libya. The Tuareg and their new allies slipped back into Mali with their weapons since Mali's northern border is an imaginary line in the Sahara.

In January 2012, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) launched its latest rebellion against Mali. With their al-Qaeda allies, the Tuareg made significant strides, especially since the Malian Army's response was total shit ineffectual. In March, a military coup in Bamako, with the stated intention of preserving Malian unity, displaced the democratically elected government but failed to stem the rebels' advance.

The Tuareg, however, discovered too late that they had made a Faustian bargain for their victory. By July, the Islamists had gained ascendancy and began imposing a strict and harsh interpretation of Sharia on the Tuareg, for whom such practices were foreign (their ideas of Sharia are much more moderate). This was akin to what happened in Afghanistan as the Taliban gained power there. The Islamists destroyed the highly culturally significant and internationally protected burial shrines contrary to Islam, although they were erected by an Islamic civilization present in the region for centuries. This cultural vandalism brings to mind the demolition of Afghanistan's Bamiyan Buddhas by the Taliban in 2001.

Europe was naturally concerned that these developments could turn Mali into a safe haven for terrorists - a new late 1990s Afghanistan. In January 2013, France began airstrikes in their former colony to prop the government, especially after the jihadists managed to take control of the strategic town of Konna. Along with the French, several other African countries (with their borders drawn by Europeans and with ethnic minorities that don't quite like being constrained within those borders) also sent reinforcements. The MNLA, realizing it would be destroyed if it sided with the jihadists, decided to change sides in the conflict, declaring a truce with the government for now.

Military rule[edit]

In 2020, president Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta was overthrown by the army, which began government by a military junta. After pressure from neighboring states including economic sanctions, elections are scheduled for 2024.[16] The increasingly unpopular French military left in February 2022, with the government instead relying on Russian mercenary group Wagner to impose order.[17] Wagner have been linked with a series of massacres of civilians, most seriously the deaths of between 350 and 380 people in Moura in March 2022, although Malian troops have also shown themselves willing to fire on unarmed civilians.[18]

Gallery[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Mali: Timbuktu heritage may be threatened, Unesco says. BBC News.

- ↑ Wolny, Philip (15 December 2013). Discovering the Empire of Mali. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 7. ISBN 9781477718896.

- ↑ Sankore University. International Museum of Muslim Cultures.

- ↑ The Empire of Mali (1230-1600). South African History Online.

- ↑ CIA World Factbook: Mali. CIA.

- ↑ Mali Travel Advisory. US State Department.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ghana Empire. Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Sundiata Keita. Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Timbuktu. Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Mansa Musa I. Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Songhai Empire. Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Mali - History. Global Security.

- ↑ A Brief History of Mali. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Mali: When France Ruled West Africa. International Business Times.

- ↑ Africa in World War II - the Forgotten Veterans. Dépêches du Mali

- ↑ Mali coup: How junta got Ecowas economic sanctions lifted, BBC News, 6 July 2022

- ↑ Why are French troops leaving Mali, and what will it mean for the region?, BBC News, 26 April 2022

- ↑ "Russian mercenaries linked to civilian massacres in Mali", The Guardian, 4 May 2022

KSF

KSF