Mexican-American War

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 11 min

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 11 min

| It never changes War |

| A view to kill |

“”[A] thing for every right-minded American to be ashamed of...

|

| —Nicholas Trist, the US diplomat who negotiated the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo |

“”"I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory.

|

| —Ulysses S. Grant |

“”After the United States gobbled up California and half of Mexico, and we were stripped down to nothing, territorial expansion suddenly becomes a crime. It's been going on for centuries, and it will still go on.

|

| —Hermann Göring during the Nuremberg trials[2] |

The Mexican-American War took place between 1846 and 1848, and was unsurprisingly a war between Mexico and the United States of America. It's also a strong candidate for the prestigious "Most Bullshit War in American History" Award, although it faces stiff competition from that clusterfuck in Indochina (or that one in Afghanistan).

Shortly after the US annexation of Texas, President James K. Polk![]() offered to purchase Mexican land that had previously been claimed by the Texans. When the Mexicans refused, he moved US troops into the disputed area, provoking an attack which he then cited before Congress as an act of aggression. The resulting war ended with America seizing a huge tract of land from Mexico that now comprises multiple states including California, New Mexico, and Arizona.

offered to purchase Mexican land that had previously been claimed by the Texans. When the Mexicans refused, he moved US troops into the disputed area, provoking an attack which he then cited before Congress as an act of aggression. The resulting war ended with America seizing a huge tract of land from Mexico that now comprises multiple states including California, New Mexico, and Arizona.

This war doesn't really show up in media, nor is it often discussed. It's certainly not as popular as WWII. This is unsurprising, as it isn't exactly hard to argue that the US was the bad guy. A deliberately instigated war of conquest doesn't exactly fit with America's national image.

Origins[edit]

The first time Texas seceded from a nation to preserve slavery[edit]

“”Having lived in Texas as a youth and been forced to study Texas history, I thought I knew the story of its admission to the Union pretty well. But I never knew the profound importance of race to that history. In particular, I did not know that Mexico had abolished slavery and that this was a key reason for the war for Texas independence. The Texans were determined to keep their slaves and were willing to fight to the death for that right.

|

| —Bruce Bartlett, wingnut historian, has a stopped clock moment[3] |

Under the rule of Spain, Texas was only sparsely populated; after gaining independence Mexico sought to increase the territory's non-native population in order to bring it under control.[4] Mexico's sparse northern population left its frontier vulnerable to raids from Native Americans who stole livestock and sold it to the United States.[5] The Mexican government began granting American families land grants in Texas, beginning a steady stream of American migration southward.[6] As an additional incentive, Mexico permitted American farmers to keep their slaves, even though Mexico itself had previously abolished slavery.[7]

As the owner of a huge land grant, Stephen Austin[note 1] became one of the most influential Americans in Texas, and he defeated several political pushes to ban slavery in Texas.[8] He also led an unsuccessful attempt to make Texas an autonomous state within Mexico. As the Anglo-American population of Texas swelled, the Mexican government became concerned with the stability of the region.[9] The situation became more tense after Mexico banned Texan slavery in 1829; the government hoped to contain the Anglo-American anger by restricting further immigration from the United States.[10] However, in an amusing reversal, American settlers either ignored or circumvented these laws and entered Mexico anyways.[11]

Meanwhile, Mexican general Antonio López de Santa Anna[12] overthrew the Mexican president and established himself as a dictator. He hoped to end the semi-independence of Texas.[7] Stephen Austin retaliated by calling his fellow Texans to begin (1835) an armed revolt.[citation needed] At this point, the only thing the rebels truly wanted was a return to Mexico's federalist government and the autonomy of Texas. The main driving impulse both then and after was to force the Mexican government to re-legalize the institution of slavery.[13]

Regardless, hostilities began when Santa Anna crushed and massacred the rebel defenders of the Alamo (March 1836), creating a rallying cry for the (white) Texans and their allies.[14] Disagreement set in among the rebels as to what their exact goal was; their assembly in 1836 eventually decided on full independence.[15] The ensuing war resulted in Santa Anna's ultimate defeat at the hands of Texan general Sam Houston; Mexico had to acknowledge Texas' independence (1836).[7] Texas won some international recognition, but later agreed (1845) to be annexed by the United States.[16]

Manifest Destiny[edit]

“”The untransacted destiny of the American people is to subdue the continent... Divine task! immortal mission! Let us tread fast and joyfully the open trail before us! Let every American heart open wide for patriotism to glow undimmed, and confide with religious faith in the sublime and prodigious destiny of his well-loved country.

|

| —William Gilpin[17] |

The United States at this point also began to think seriously about acquiring California. California had also received high levels of immigration from the United States, and Santa Anna's shenanigans even resulted in an abortive attempt at a declaration of independence (June 1846) there.[18] Disagreements over a potential annexation of California caused divisions in the Democratic Party leading up to the election of 1844; James Polk came out on top, favoring annexation.[19] Particularly important in his campaign rhetoric was the concept of Manifest destiny, the idea that white Americans were destined to expand across the entire North American continent. Polk most especially coveted the city of San Francisco, site of North America's largest Pacific harbor, as he wanted to turn the city into America's trade hub with China, Japan and the rest of East Asia.[20]

The Nueces Strip dispute[edit]

“”We were sent to provoke a fight, but it was essential that Mexico should commence it. It was very doubtful whether Congress would declare war; but if Mexico should attack our troops, the Executive could announce, "Whereas, war exists by the acts of, etc.," and prosecute the contest with vigor. Once initiated there were but few public men who would have the courage to oppose it. ...

|

| —Ulysses S. Grant[21] |

Even after Texas' successful war for independence, its exact border with Mexico was never fully settled. Mexico insisted that Texas' southern boundary was the Nueces river, while Texas claimed everything north of the Rio Grande.[22] This dispute was not resolved after the annexation of Texas, and the territorial claim was more or less inherited by the United States. The inhabitants of the Nueces strip, meanwhile, were largely Native Americans and outlaws who weren't especially sympathetic to either party.[23] President Polk, however, didn't really care much for the little strip of desert. He sent Commissioner John Slidell to negotiate over the boundary, but also gave him instructions to primarily focus on an offer to buy California for $25 million.[24] This pissed the Mexicans right off, because they had expected the Americans to offer a settlement on the whole Texas issue but instead found that the Americans intended yet more territorial expansion at Mexico's expense. Polk likely expected negotiations to fall through, and he dispatched troops into the Nueces area with the deliberate intention of provoking a response from Mexico.[25] Mexico took the bait, and Polk got his war.

A Brief Summary of the War[edit]

The war was pretty short and straightforward, so rather than give an in-depth run-down of the war and its battles, here's a brief summary:

As mentioned earlier, President Polk basically had American troops wandering around Texas in the hopes that Mexican forces would rashly attack. He got his wish on April 25, 1846 when a large force of Mexican cavalry attacked a small American patrol near the Texas-Mexico border.[26] Polk used the attack as grounds for a declaration of war, which he got with little difficulty.[27] Thus the war began in earnest. The Mexicans followed up that initial skirmish by besieging a small American fort along the Texas-Mexico border.[28] The Americans responded by sending their navy to blockade Mexican ports in the Pacific and Gulf of Mexico, while also sending four armies to invade Mexican territory. The American plan more or less played out thusly:

- The first army, led by Stephen Kearny,

marched into what is now New Mexico and occupied it. While there, he set up a government and laws, and put down some rebellions.[29] Eventually he marched through Arizona and into southern California, which his army occupied.[30]

marched into what is now New Mexico and occupied it. While there, he set up a government and laws, and put down some rebellions.[29] Eventually he marched through Arizona and into southern California, which his army occupied.[30] - The second force, a smaller army led by John C. Fremont,

happened to be scouting around northern Utah/California when it got word that the war had begun. The army proceeded to march to San Francisco, California where it linked up with naval forces.[31] American settlers launched a "bear flag revolt" similar to what had happened in Texas oh so recently, and helped overthrow the Mexican government in California.[32] The US forces, consisting of naval troops under Robert F. Stockton,

happened to be scouting around northern Utah/California when it got word that the war had begun. The army proceeded to march to San Francisco, California where it linked up with naval forces.[31] American settlers launched a "bear flag revolt" similar to what had happened in Texas oh so recently, and helped overthrow the Mexican government in California.[32] The US forces, consisting of naval troops under Robert F. Stockton, the Bear Flag rebels, and the small armies led by Fremont and Kearny, made a separate peace treaty with the local Mexican forces[33] and occupied the region.

the Bear Flag rebels, and the small armies led by Fremont and Kearny, made a separate peace treaty with the local Mexican forces[33] and occupied the region. - The third force, led by Zachary Taylor, attacked and drove back the Mexican forces in southern Texas and launched an invasion of northern Mexico.[34] The army probably should've been defeated in the Battle of Buena Vista;

however, even though it was winning, the significantly larger Mexican army was starving and exhausted, and with rumors of a rebellion breaking out elsewhere, it chose to simply leave.[35] The Americans of course claimed victory, as one does, and Taylor was suddenly a war hero.[note 2] The army proceeded to occupy a large swath of northeastern Mexico.

however, even though it was winning, the significantly larger Mexican army was starving and exhausted, and with rumors of a rebellion breaking out elsewhere, it chose to simply leave.[35] The Americans of course claimed victory, as one does, and Taylor was suddenly a war hero.[note 2] The army proceeded to occupy a large swath of northeastern Mexico. - The fourth and largest army, led by Winfield Scott,

was sent to Mexico by sea and conducted the U.S.'s largest amphibious assault until World War II when it landed near the important Mexican port city of Veracruz.

was sent to Mexico by sea and conducted the U.S.'s largest amphibious assault until World War II when it landed near the important Mexican port city of Veracruz. The army subsequently besieged and captured the city, after which Scott's force marched west toward Mexico City. Not far from Veracuz at Cerro Gordo

The army subsequently besieged and captured the city, after which Scott's force marched west toward Mexico City. Not far from Veracuz at Cerro Gordo Scott's army decisively defeated that Mexican army[note 3] that had walked away from the battle at Buena Vista, leaving Mexico City unprotected.[36] Scott's army occupied the capital after a handful of short, lopsided battles.

Scott's army decisively defeated that Mexican army[note 3] that had walked away from the battle at Buena Vista, leaving Mexico City unprotected.[36] Scott's army occupied the capital after a handful of short, lopsided battles. [37] Like Taylor, Scott was suddenly a war hero.

[37] Like Taylor, Scott was suddenly a war hero.

With large portions of Mexico under American occupation, and the Mexican capital having just fallen, the fighting largely ended. The Mexicans were forced to sue for peace after only about a year and a half of getting their asses kicked. On February 2nd, 1848, about four months after the fall of Mexico City, the peace treaty was signed and the war was officially over.

Domestic reaction in the US[edit]

“”"Allow the President to invade a neighboring nation whenever he shall deem it necessary to repel an invasion, and you allow him to do so whenever he may choose to say he deems it necessary for such purpose, and you allow him to make war at pleasure. Study to see if you can fix any limit to his power in this respect, after having given him so much as you propose.

|

| —Abraham Lincoln[38] |

The abolitionists in the North saw the Mexican-American War for what it really was: a cynical attempt by Polk to expand the US on false pretenses. Whig and Liberty Party members were convinced that Polk was conspiring to make whatever territory he got from Mexico into new slave states in order to expand the political power of The South.[39] Abraham Lincoln, a freshman Whig in the House of Representatives, was a highly vocal opponent of the war. He famously challenged Polk's claim that "American blood has been shed on American soil" by demanding that Polk "show me the spot where American blood was shed" while introducing eight resolutions questioning the war's constitutionality.[40] Lincoln's unpatriotic stance on the war was unpopular with his Illinois constituents; he was given the nickname "Spotty Lincoln," called a disgrace, and finally declined to run for office.[41] Abraham Lincoln, the first Republican Party president, is to this day a popular figure in Mexico.[40]

In 1846, amidst the ongoing war, President Polk proposed an appropriation measure that would allocate $2 million to purchase any land that Mexico might happen to suddenly offer on sale.[42] This was Polk's first public admission that there might be more to the Mexican-American War than his national defense story. However, Northern Democratic Representative David Wilmot foiled the plan by offering an amendment on the bill which would permanently forbid slavery in any land ceded to the United States by Mexico.[43] The Wilmot Proviso, as it was called, was supported by an unusual bipartisan coalition of abolitionist Whigs and Northern Democrats who still resented Polk for gaining the presidential nomination over Martin Van Buren and wanted to fuck him over.[42] Although Wilmot's amendment sank in the Southerner-dominated Senate, it was a sign of the increasing strength of the abolitionist movement.

Resolution and Aftermath[edit]

Territorial changes[edit]

“”In the Mexican War itself, in case you don't know it, we appropriated 60 percent of the land area of Mexico as it was then defined through the Spanish Conquest. So we increased the size of the United States by 40 percent and reduced Mexico by 60 percent.

|

| —Henry Jaffa, American Civil War historian[44] |

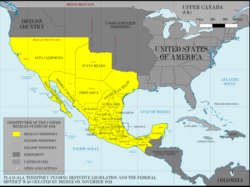

Heavily outmatched, and with many of its major cities occupied, Mexico had no choice but to agree to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ending the war. Mexico ceded the present-day states of California, Nevada, and Utah, most of New Mexico, Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming in exchange for $15 million, less than half of what Polk had originally offered.[45] The fact that the US actually paid (a relative pittance) for the territory led the Whig-run National Intelligencer to sarcastically declare, "we take nothing by conquest.... Thank God."[46] To lessen the blow on Mexico even further, the US government promised in the treaty to wipe out the Comanche and Apache tribes, who had been attacking northern Mexico.[47] Uh, that was nice of them? Of course, even though killing Indians was the US's favorite pastime, even then they squirmed out of that obligation during the Gadsden Purchase.![]() [48]

[48]

Setting the stage for civil war[edit]

“”The Southern rebellion was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican war. Nations, like individuals, are punished for their transgressions. We got our punishment in the most sanguinary and expensive war of modern times.

|

| —Ulysses S. Grant[49] |

Most of the major military figures of the American Civil War got their first taste of the action as junior officers in the Mexican war.[50] Ulysses S. Grant, George B. McClellan, William T. Sherman, George Meade, and Ambrose Burnside were among those on the Union side who served in Mexico. Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, James Longstreet, Joseph E. Johnston, Braxton Bragg, Sterling Price, and the future Confederate President Jefferson Davis represented the South.

The bitter partisan conflict over the war also led to the rise of Lincoln's Republican Party and greatly exacerbated national tensions over slavery.

See also[edit]

More bullshit American wars[edit]

- American Indian Wars

- War of 1812

- U.S. conquest of Hawaii

- Spanish-American War

- Vietnam War

- Iraq War

- Afghanistan War

Notes[edit]

- ↑ For whom the capital of Texas is named

- ↑ Taylor would use his war hero status to win the 1848 U.S. presidential election.

- ↑ Which was personally led by the Mexican president, General Antonio López de Santa Anna

References[edit]

- ↑ Morgan, Robert. Lions of the West: Heroes and Villains of the Westward Expansion. North Carolina: Algonquin Books. p. 390. ISBN 978-1-61620-189-0.

- ↑ Hermann Göring Quote

- ↑ Mexican-American War Wikiquote

- ↑ Pedro Santoni, "U.S.-Mexican War" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 1511

- ↑ DeLay, Brian (Feb 2007), "Independent Indians and the U.S. Mexican War," The American Historical Review, Vol. 112, No. 2, p. 3.

- ↑ Jesús F. de la Teja, "Texas Secession" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, 1403-04.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Texas Revolution Britannica

- ↑ Stephen Austin Britannica

- ↑ Lack, Paul D. (1992). The Texas Revolutionary Experience: A Political and Social History 1835–1836. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 0-89096-497-1. p. 5

- ↑ Edmondson, J.R. (2000). The Alamo Story: From Early History to Current Conflicts. Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press. ISBN 1-55622-678-0. p. 80

- ↑ Baptist, Edward (2014). The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04966-0. p. 266.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Antonio López de Santa Anna.

- ↑ Chang, Robert S. "Forget the Alamo: Race Courses as a Struggle over History and Collective Memory." Berkeley La Raza Law Journal 13.Article 1 (2015). Print.

- ↑ 15 Facts About the Battle of the Alamo Minster, Christopher. ThoughtCo, January 25, 2019

- ↑ Roberts, Randy; Olson, James S. (2001). A Line in the Sand: The Alamo in Blood and Memory. The Free Press. ISBN 0-684-83544-4. p. 98

- ↑ Republic of Texas Texas State Historical Association, archived.

- ↑ William Gilpin Wikiquote

- ↑ The Annexation of California from Mexico Study.com

- ↑ Mark R. Cheathem; Terry Corps (2016). Historical Dictionary of the Jacksonian Era and Manifest Destiny. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 139. ISBN 9781442273207

- ↑ President Polk and the Taking of the West Constitutional Rights Foundation.

- ↑ Personal Memoirs Chapter IV.

- ↑ Nueces Strip

- ↑ Teague, Wells (2000). Calling Texas Home: A Lively Look at What It Means to Be a Texan. Council Oak Books. pp. 23–24. ISBN 9781885171382.

- ↑ Commissioner John Slidell PBS.

- ↑ James K. Polk and the U.S. Mexican War: A Policy Appraisal A Conversation With David M. Pletcher, Indiana University. PBS.

- ↑ The Thornton Affair — The First Bloodshed of the Mexican-American War, American History Central

- ↑ The Senate Votes for War against Mexico, The U.S. Senate

- ↑ Fort Texas / Fort Brown, National Park Service

- ↑ Taos, New Mexico Revolt, Legends of America

- ↑ Stephen Kearny – Father of the U.S. Cavalry, Legends of America

- ↑ This week in history: John C. Frémont is court-martialed for mutiny, Deseret Times

- ↑ Bear Flag Revolt, History.com

- ↑ Capitulation of Cahuenga, Los Angeles Almanac

- ↑ Zachary Taylor, PBS

- ↑ Battle of Buena Vista, February 1847, Landmark Events

- ↑ Mexican-American War 170th: Battle of Cerro Gordo, Emerging Civil War

- ↑ General Winfield Scott captures Mexico City, History.com

- ↑ Abraham Lincoln's Warning About Presidents and War

- ↑ Mexican War Ohio History Central.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Why Abraham Lincoln Was Revered in Mexico Smithsonian Magazine

- ↑ Congressman Lincoln 1847-1849 National Park Service.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 The Wilmot Proviso American Battlefield Trust

- ↑ Wilmot Proviso Britannica

- ↑ The Real Abraham Lincoln

- ↑ Mills, Bronwyn. U.S.-Mexican War. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8160-4932-5.

- ↑ "We take nothing by conquest, thank God."

- ↑ Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo; February 2, 1848 Avalon Project

- ↑ DeLay, Brian (2008). War of a thousand deserts: Indian raids and the U.S.-Mexican War. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 302.

- ↑ Ulysses S. Grant Wikiquote

- ↑ 10 Civil War Generals Who Served in the Mexican-American War ThoughtCo

KSF

KSF