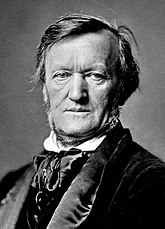

Richard Wagner

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 7 min

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 7 min

| Time to put on some Music |

| Soundtrack |

| Musicians |

“”Wagner's music is much better than it sounds.

|

| —Edgar Wilson Nye[1] |

Richard Wagner (1813–1883) was a German Romantic composer of opera. He was one of the most famous and influential opera composers in history; he essentially invented leitmotifs, a system of writing operatic music that serves as the basis of most modern film scores. He also was innovative in the complexity of his music, inspiring the atonal works of composers like Arnold Schoenberg and Igor Stravinsky, and invented various new ways to stage an opera.

Trivia[edit]

Wagner was a 19th century person through and through and he was born in one petty German kingdom (Saxony) and ultimately died in the employ of another German monarch (Ludwig II of Bavaria, of Neuschwanstein fame). He built a house in Bayreuth with the odd name Wahnfried and had a new opera house built that is still used exclusively for Wagner music once a year and sits empty during the rest of the year. If you say anything against Wagner in Bayreuth, the townsfolk will chase you out of their Wagner shrine with torches and pitchforks.

Music[edit]

“”Parsifal is the kind of opera that starts at six o'clock and after it has been running for three hours, you check your watch and it says 6:20.

|

| —David Randolph |

Wagner's compositions were mainly operas. He did write a few purely instrumental pieces; however, they are mostly considered insignificant next to the monoliths in music history that are his operas. His middle and late works are rich in their complex harmonies and orchestrations, as well as their elaborate use of leitmotifs. It is his operatic cycle in four parts Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung) that is his most famous work. Though some might not be aware, most people have heard his music, as he tends to be a popular choice for musical cues and stings:

- The Bridal Chorus from Lohengrin[2] (and less frequently Elsa's Procession to the Cathedral from the same)

- Vorspiel (Prelude) to Das Rheingold[3] (the first opera in the Ring cycle)

- Ride of the Valkyries from Die Walküre[4] (the second opera in the Ring cycle)

- Siegfried's Funeral March from Götterdämmerung[5] (the fourth opera in the Ring cycle), though not as famous as the above

- Apparently the only symphony Wagner completed, at that age that tends to be infused with a certain fernweh—nineteen years young[6]: Symphony in C Major.

He was also responsible for the creation of the instrument known as the Wagnertube (plural Wagnertuben, often mistranslated Wagner tuba/tubas), which fills the "hole" between the brassier sound of a trombone and the smoother sound of a horn.

Anti-Semitism[edit]

Outside of his lengthy music and distinct operatic style, Wagner is often remembered today as being anti-Semitic; he famously wrote a pamphlet called "Jewishness in Music",![]() decrying most Jewish composers and poets of his time as owing their success to hype, and not possessing any remarkable talent. These views didn't stop Gustav Mahler, a Jewish Austro-German contemporary of Wagner, from idolising him and respecting his music greatly. Both Wagner's views and music were said to become inspirational to Adolf Hitler (although this wasn't shared by all members of the Third Reich), who viewed them as quintessentially German. Of course, Hitler also viewed Chopin's music as inspirational. So, despite Chopin's Polish heritage, and Nazi view of the music of the Second Vienna School as degenerate because… umm... something (apparently he smelled one Jew too many).[note 1] Wagner's antisemitism and popularity among the Nazi leaders was the reason why his music can't really get a foot in the door in Israel to this day, even though pre-WWII, his music was rather popular among the Zionist movement in general and with Theodor Herzl and the Palestine Orchestra[note 2] in particular.

decrying most Jewish composers and poets of his time as owing their success to hype, and not possessing any remarkable talent. These views didn't stop Gustav Mahler, a Jewish Austro-German contemporary of Wagner, from idolising him and respecting his music greatly. Both Wagner's views and music were said to become inspirational to Adolf Hitler (although this wasn't shared by all members of the Third Reich), who viewed them as quintessentially German. Of course, Hitler also viewed Chopin's music as inspirational. So, despite Chopin's Polish heritage, and Nazi view of the music of the Second Vienna School as degenerate because… umm... something (apparently he smelled one Jew too many).[note 1] Wagner's antisemitism and popularity among the Nazi leaders was the reason why his music can't really get a foot in the door in Israel to this day, even though pre-WWII, his music was rather popular among the Zionist movement in general and with Theodor Herzl and the Palestine Orchestra[note 2] in particular.

Television and film star and National Treasure Stephen Fry is also a massive fan of Wagner despite also being culturally Jewish, and in 2010 made a documentary on the subject which focused partially on this disconnect between Fry's heritage and Wagner's views. Musicologists who think that it is impossible to separate the art from the artist are often confused by this, but evidently, it is possible.

Family connections to Nazis[edit]

One could, of course, theorize that Wagner would've been appalled by the Nazis since he was a socialist and Nazis are, well, you know, fascist.[8] However, many of Wagner's descendants and relations ended up being significantly involved in the Nazi movement, particularly after 1923, when Adolf Hitler visited Bayreuth. This visit resulted in the Wagner family becoming early members of the Nazi party over shared German nationalist sentiment, as well as Hitler's huge interest in Wagner's music (and the management of such by Wagner's family).[9][10] In particular, Winifred Wagner,![]() the wife of Wagner's bisexual [note 3] son Siegfried,

the wife of Wagner's bisexual [note 3] son Siegfried,![]() was very close to Hitler. In 1924, the Wagners traveled to America in order to raise money for the Bayreuth Festival

was very close to Hitler. In 1924, the Wagners traveled to America in order to raise money for the Bayreuth Festival![]() (the annual festival devoted to Wagner's music). During this visit, they also solicited money from Henry Ford to support Hitler's cause. Later that year, Winifred and Siegfried traveled to Munich to witness the Beer Hall Putsch.

(the annual festival devoted to Wagner's music). During this visit, they also solicited money from Henry Ford to support Hitler's cause. Later that year, Winifred and Siegfried traveled to Munich to witness the Beer Hall Putsch.![]() After Hitler was sent to prison for the failed putsch, Winifred wrote multiple supportive letters to him (along with parcels of items to support his prison stay).[12][13] Later, as Hitler increasingly visited Bayreuth and the Wagner family, Winifred gave Hitler the nickname "Wolf" and introduced him into her children's lives as a friendly uncle figure.[14] The closeness was to the point where gossips of the time speculated that Hitler was having an affair with Winifred (a widow since Siegfried's death in 1930), or even speculated that Hitler was having an affair with Winifred's youngest daughter, Verena Wagner Lafferentz.

After Hitler was sent to prison for the failed putsch, Winifred wrote multiple supportive letters to him (along with parcels of items to support his prison stay).[12][13] Later, as Hitler increasingly visited Bayreuth and the Wagner family, Winifred gave Hitler the nickname "Wolf" and introduced him into her children's lives as a friendly uncle figure.[14] The closeness was to the point where gossips of the time speculated that Hitler was having an affair with Winifred (a widow since Siegfried's death in 1930), or even speculated that Hitler was having an affair with Winifred's youngest daughter, Verena Wagner Lafferentz.![]() [14][15]

[14][15]

Synchronizing with the Wagner family's friendship with Hitler, the Bayreuth Festival increasingly was hijacked by the Völkisch movement during the rise of the Nazis in the 1920s, to the chagrin of Wagner fans that did not share this movement's ultra-nationalism and racism.[14][16] By 1934, the integration with Hitler had grown even stronger. Hitler was paying an annual subsidy of 100,000 marks a year to the Bayreuth festival, and making frequent weekend retreats there.[11][17] As a case in point, in July 1936, Hitler authorized German intervention on the side of Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War at Bayreuth, while on his way back to his guest quarters at Villa Wahnfried (the Wagner family residence), after attending a performance of Wagner's Siegfried.![]() Such was Hitler's devotion to Wagner that he code-named this effort Operation Feuerzauber

Such was Hitler's devotion to Wagner that he code-named this effort Operation Feuerzauber![]() ("Operation Magic Fire"), named after the "magic fire" music scene in another Wagner opera, Die Walküre.

("Operation Magic Fire"), named after the "magic fire" music scene in another Wagner opera, Die Walküre.![]() [18][19]

[18][19]

In addition, one of Wagner's daughters (Eva![]() ) married Houston Stewart Chamberlain in 1908. Houston Stewart Chamberlin was an English philosopher that became obsessed with Wagner after he attended an 1882 performance of Wagner's opera Parsifal

) married Houston Stewart Chamberlain in 1908. Houston Stewart Chamberlin was an English philosopher that became obsessed with Wagner after he attended an 1882 performance of Wagner's opera Parsifal![]() at Bayreuth. From that point forward, he fell into a circle of Wagner-devoted intellectuals, influenced by the anti-Semitic writings of Wagner late in life (which were derived, in part, by the scientific racism babble of Arthur de Gobineau). This led to him adapting all of the fundamental attitudes of the German Völkisch movement in the 1890s — a hatred of modernism (as represented by the city and the Jew), a fanatical belief in the need for racial purity, and a conviction that only the Germans could save the world and that to do so they must purify their own German stock and their own German faith. Ultimately, this culminated in the publication of the book The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century

at Bayreuth. From that point forward, he fell into a circle of Wagner-devoted intellectuals, influenced by the anti-Semitic writings of Wagner late in life (which were derived, in part, by the scientific racism babble of Arthur de Gobineau). This led to him adapting all of the fundamental attitudes of the German Völkisch movement in the 1890s — a hatred of modernism (as represented by the city and the Jew), a fanatical belief in the need for racial purity, and a conviction that only the Germans could save the world and that to do so they must purify their own German stock and their own German faith. Ultimately, this culminated in the publication of the book The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century![]() in 1899, a book that combined his occupation with racial purity with philosophical "Goethean science.

in 1899, a book that combined his occupation with racial purity with philosophical "Goethean science.![]() " Though by modern reviews this book seems turgid, rambling, repetitive, and "pretentious rubbish", the book was a best-seller of the time (selling over 100,000 books by 1915) due to Houston Chamberlain's ability to encode crass prejudice in a pseudo-intellectual, pseudo-scientific language. Essentially, it helped codify the philosophical underpinnings behind the formulation of Nazi ideology; indeed, Houston Chamberlain joined the Nazi party in 1923, and both Hitler and Joseph Goebbels attended Chamberlain's funeral in 1927.[20][21][22]

" Though by modern reviews this book seems turgid, rambling, repetitive, and "pretentious rubbish", the book was a best-seller of the time (selling over 100,000 books by 1915) due to Houston Chamberlain's ability to encode crass prejudice in a pseudo-intellectual, pseudo-scientific language. Essentially, it helped codify the philosophical underpinnings behind the formulation of Nazi ideology; indeed, Houston Chamberlain joined the Nazi party in 1923, and both Hitler and Joseph Goebbels attended Chamberlain's funeral in 1927.[20][21][22]

While Winifred remained devoted to Hitler long after the war ended, [14] this devotion did not completely extend to the rest of the family. Winifred's elder daughter Friedelind![]() was an outspoken opponent of Nazism, to the point where she had to flee Germany during the heart of World War II.[23]

was an outspoken opponent of Nazism, to the point where she had to flee Germany during the heart of World War II.[23]

Legacy[edit]

Wagner's influence on literature and philosophy is significant. Friedrich Nietzsche was a member of Wagner's inner circle during the early 1870s, and his first published work, The Birth of Tragedy![]() , proposed Wagner's music as the Dionysian "rebirth" of European culture in opposition to Apollonian rationalist "decadence". Nietzsche broke with Wagner following the first Bayreuth Festival, believing that Wagner's final phase represented a pandering to Christian pieties and a surrender to the new German Reich. Nietzsche expressed his displeasure with the later Wagner in "The Case of Wagner" and "Nietzsche contra Wagner".[24]

, proposed Wagner's music as the Dionysian "rebirth" of European culture in opposition to Apollonian rationalist "decadence". Nietzsche broke with Wagner following the first Bayreuth Festival, believing that Wagner's final phase represented a pandering to Christian pieties and a surrender to the new German Reich. Nietzsche expressed his displeasure with the later Wagner in "The Case of Wagner" and "Nietzsche contra Wagner".[24]

In the 20th century, W. H. Auden once called Wagner, "perhaps the greatest genius that ever lived", while Thomas Mann and Marcel Proust were heavily influenced by him and discussed Wagner in their novels. He is also discussed in some of the works of James Joyce. Wagnerian themes inhabit T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land, which contains lines from "Tristan und Isolde" and "Götterdämmerung", and Verlaine's poem on Parsifal.[25]

Many of Wagner's concepts, including his speculation about dreams, predated their investigation by Sigmund Freud. Wagner had publicly analysed the Oedipus myth before Freud was born in terms of its psychological significance, insisting that incestuous desires are natural and normal, and perceptively exhibiting the relationship between sexuality and anxiety. Georg Groddeck considered the Ring as the first manual of psychoanalysis.[26]

See also[edit]

- Friedrich Nietzsche, the other much-Godwinned one, completely undeservedly so.

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Bonus "w0t" value can be found in the fact that Wagner's complex harmonies, more or less unapologetic dissonances, and ambiguous tonalities are commonly viewed by music historians as a major milestone along the road to complete atonality as practiced by the Second Viennese School.

- ↑ Later the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra,

which had an effective ban on Wagner for five decades.[7]

which had an effective ban on Wagner for five decades.[7]

- ↑ Unsurprisingly, Siegfried's bisexuality was a significant source of contention at the time... not only due to family viewpoints, but due to the need to pay off newspapers to suppress stories that, due to the homophobic climate of the time, would have been seriously damaging.[11] A contemporaneous example of the type of scandal the Wagners would have been worried about is the Eulenburg affair.

References[edit]

- ↑ Quote Investigator

- ↑ See 3:23

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wiyoLa9z1ao

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7AlEvy0fJto

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a53s4jyCqqU

- ↑ https://classicalartsuniverse.com/richard-wagner-symphony-in-c-major/ “Considered to be the only symphony that Wagner completed”]

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/1991/12/16/arts/old-agonies-revive-israeli-philharmonic-to-perform-wagner.html

- ↑ "Richard Wagner"

- ↑ "Bayreuth and National Socialism", DW.com, 2012 July 24

- ↑ [Hamann, Brigitte. Winifred Wagner: A Life At the Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth Orlando: Harcourt, 2006. pp59-60

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "The Bayreuth Festival preview: Let the madness begin!" by Adrian Mourby, Independent, 2013 July 20

- ↑ [Hamann, Brigitte. Winifred Wagner: A Life At the Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth Orlando: Harcourt, 2006. pp63-71

- ↑ ‘My dear, dear friend and Führer!’ by Jeremy Adler, London Review of Books, 2006 July 6

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 "At home with the Wagners", by Lucasta Miller, Guardian, 2005 August 19

- ↑ "Verena Lafferentz, 98, Last of Wagner Grandchildren, Is Dead" by Sam Roberts, New York Times, 2019 April 23

- ↑ "A Widow’s Might" by Geoffrey Wheatcroft, New York Times, 2007 March 11

- ↑ "Music: Hitler Over Bayreuth", Time, 1934 January 8

- ↑ "These people are intolerable" by Richard J. Evans, London Review of Books, November 2015

- ↑ "Klingsor's Apprentices" by James Joll, New York Review, 1985 January 31

- ↑ "Ravings of a Renegade" by James Joll, New York Review, 1981 September 24

- ↑ [Johann Chapoutot, “From Humanism to Nazism: Antiquity in the Work of Houston Stewart Chamberlain”, Miranda [Online], 11|2015

- ↑ "Houston Stewart Chamberlain: was this British 'philosopher' the first Nazi?" by Rupert Christiansen, Telegraph, 2017 January 10

- ↑ "Obituary: Friedelind Wagner, 73, Opponent Of Nazism Despite Family's Ties" by John Rockwell, New York Times, 1991 May 9

- ↑ Magee (1988) 52

- ↑ Magee (1988) 47

- ↑ Picard (2010) 759

KSF

KSF