Sugar

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 12 min

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 12 min

| Potentially edible! Food woo |

| Fabulous food! |

| Delectable diets! |

| Bodacious bods! |

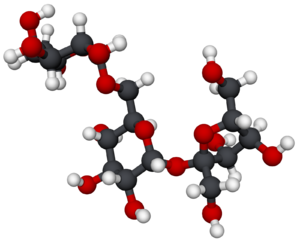

Sugar is a "sweet-tasting, short-chain, soluble carbohydrate"[1], and can refer to a number of related molecules including sucrose (cane sugar), fructose (fruit sugar), and glucose. Sugar is found in many foodstuffs, including candy/sweets/chocolate, non-diet carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks, many alcoholic drinks, breakfast cereals, fruit, milk, and a surprising number of processed foods.

Human beings appear to have an innate fondness for sweet foods, which made sense when that meant fruit or maybe honey, but today thanks to the cultivation of sugar cane (Saccharum officinarum) and sugar beet (Beta vulgaris), sugar is a cheap and almost ubiquitous product of industrialised agriculture.[2] Sugar is controversial in the field of public health. Along with other high-calorie foods, it is blamed for high rates of obesity and diabetes, but there are arguments over whether sugar, particularly fructose, is more dangerous than fat or starch. As yet, the evidence is inconclusive.

Taxes on sugar are increasingly being used to attempt to reduce sugar consumption. There is evidence that they reduce sales, but less as to their effect on health.

Types of sugar[edit]

Chemists know many different types of sugar. Most common are monosaccharides (simple sugars), and disaccharides, which comprise 2 monosaccharides bonded together in a single molecule. Oligosaccharides (which are found in plant fiber) typically include three to ten simple sugars, and may be difficult for mammals to digest without gassy by-products such as methane. A few of the more common sugars are listed below.

Monosaccharides[edit]

- Glucose

: Used directly in the human body for energy. For this reason it's often found in energy drinks, as well as being used in baking and sweet/candy-making. Most starch consumed is metabolised by the body to glucose.

: Used directly in the human body for energy. For this reason it's often found in energy drinks, as well as being used in baking and sweet/candy-making. Most starch consumed is metabolised by the body to glucose. - Fructose

: A very sweet sugar, obtained commercially by processing sugar cane, beet, or corn (maize, Zea mays). It is a key constituent of high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) but is also found in fruit. The body doesn't directly use fructose but requires some other processes to convert it to usable forms, which may place a strain in the liver. The amounts found in fruits are safe, as safe as 'natural' can really be, but the high concentrations found in HFCS and sucrose may be a bit much.

: A very sweet sugar, obtained commercially by processing sugar cane, beet, or corn (maize, Zea mays). It is a key constituent of high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) but is also found in fruit. The body doesn't directly use fructose but requires some other processes to convert it to usable forms, which may place a strain in the liver. The amounts found in fruits are safe, as safe as 'natural' can really be, but the high concentrations found in HFCS and sucrose may be a bit much. - Galactose

: A product of digesting lactose, galactose is less sweet than glucose or fructose, and is less important commercially. (Not to be confused with Galactus, the planet-eating Marvel villain.)

: A product of digesting lactose, galactose is less sweet than glucose or fructose, and is less important commercially. (Not to be confused with Galactus, the planet-eating Marvel villain.) - Ribose

: A sugar found present in virtually all life, as part of deoxyribonucleic acid, a.k.a., DNA. Doesn't taste very sweet at all.

: A sugar found present in virtually all life, as part of deoxyribonucleic acid, a.k.a., DNA. Doesn't taste very sweet at all. - Allulose

: A rare sugar found in some fruit, but it is mostly made by fermenting corn to convert the Glucose.

: A rare sugar found in some fruit, but it is mostly made by fermenting corn to convert the Glucose.

Disaccharides[edit]

- Sucrose

: Fructose-glucose. Table sugar, your basic standard sweetening agent like momma used, obtained from sugar cane and sugar beet. Traditionally used to sweeten tea or coffee and in baking.

: Fructose-glucose. Table sugar, your basic standard sweetening agent like momma used, obtained from sugar cane and sugar beet. Traditionally used to sweeten tea or coffee and in baking. - Lactose

: Galactose-glucose. One of the main constituents of milk (both cow and human). While (almost) all babies can digest it, people who are lactose-intolerant are unable to process it when they grow older.

: Galactose-glucose. One of the main constituents of milk (both cow and human). While (almost) all babies can digest it, people who are lactose-intolerant are unable to process it when they grow older. - Maltose

: Glucose-glucose. Malt sugar, often the result of processing grains for production of malt, to be processed into other, more useful products. Rice syrup, used as a sweetener in some pancake syrup, contains a lot of maltose.

: Glucose-glucose. Malt sugar, often the result of processing grains for production of malt, to be processed into other, more useful products. Rice syrup, used as a sweetener in some pancake syrup, contains a lot of maltose.

Trisaccharides[edit]

- Raffinose

: Galactose-glucose-fructose. A very common oligosaccharide, but only really notable for being indigestible to most mammals, and thus has... other results. It is infamously found in large quantities in beans and cabbage. The end result from ingesting these is quite a bit of gas, as while you can't digest it, your gut bacteria can. Raffinose is the largest input of methane from cattle and other farm animals, which contributes a fair bit to global warming. The gas can theoretically be reduced by using supplements that add enzymes to digest raffinose (also reducing the amount of food needed), or by genetically engineering animal feed to produce less raffinose or whatever.

: Galactose-glucose-fructose. A very common oligosaccharide, but only really notable for being indigestible to most mammals, and thus has... other results. It is infamously found in large quantities in beans and cabbage. The end result from ingesting these is quite a bit of gas, as while you can't digest it, your gut bacteria can. Raffinose is the largest input of methane from cattle and other farm animals, which contributes a fair bit to global warming. The gas can theoretically be reduced by using supplements that add enzymes to digest raffinose (also reducing the amount of food needed), or by genetically engineering animal feed to produce less raffinose or whatever. - Maltotriose

: Glucose-glucose-glucose. One of the intermediate breakdown products of starch, produced (along with maltose) by the amylase in human saliva.

: Glucose-glucose-glucose. One of the intermediate breakdown products of starch, produced (along with maltose) by the amylase in human saliva.

Polysaccharides[edit]

- Glycogen

: Tens to hundreds of glucose molecules bonded to a protein core, so technically this is a glycoprotein rather than a sugar. This is how animals (and fungi) store glucose for near-term use, largely in the muscles and liver. Excess blood sugar is dumped into your glycogen stores first, and when that's full it's to the fat cells. Likewise, when using energy, cells drain the sugar from your blood and glycogen stores get released to maintain blood sugar levels, and when that's low, fat cells release various fatty acids for the rest of the body to use (these metabolize slower, so your body is more sluggish during this time). Fat is used for long-term storage as Glycogen stores comparatively little energy for its weight. Each gram of glycogen also causes your body to hold 10 grams of water; this is the "water weight" you lose first when going on a diet. A human typically has 300g of glycogen (about 1200 calories) that need to be used up before actual fat loss occurs.

: Tens to hundreds of glucose molecules bonded to a protein core, so technically this is a glycoprotein rather than a sugar. This is how animals (and fungi) store glucose for near-term use, largely in the muscles and liver. Excess blood sugar is dumped into your glycogen stores first, and when that's full it's to the fat cells. Likewise, when using energy, cells drain the sugar from your blood and glycogen stores get released to maintain blood sugar levels, and when that's low, fat cells release various fatty acids for the rest of the body to use (these metabolize slower, so your body is more sluggish during this time). Fat is used for long-term storage as Glycogen stores comparatively little energy for its weight. Each gram of glycogen also causes your body to hold 10 grams of water; this is the "water weight" you lose first when going on a diet. A human typically has 300g of glycogen (about 1200 calories) that need to be used up before actual fat loss occurs. - Starch

: What plants use instead of glycogen. It's made of many many glucose monomers, but unlike glycogen it lacks a protein core.

: What plants use instead of glycogen. It's made of many many glucose monomers, but unlike glycogen it lacks a protein core. - Cellulose

: Also known as dietary fiber, this is what plants use in creating cell walls. Unlike starch, the glucose monomers in cellulose are bound by beta acetal linkages instead of alpha groups. This makes cellulose impossible for humans to digest, as we lack the necessary enzymes to break the glucose molecules apart. Since we can't digest it, cellulose hardens our stools, making our poop come out easier.

: Also known as dietary fiber, this is what plants use in creating cell walls. Unlike starch, the glucose monomers in cellulose are bound by beta acetal linkages instead of alpha groups. This makes cellulose impossible for humans to digest, as we lack the necessary enzymes to break the glucose molecules apart. Since we can't digest it, cellulose hardens our stools, making our poop come out easier.

Health implications[edit]

Obesity is associated with many health problems and risks. Excessive consumption of any high calorie food will result in weight gain. However, scientists argue whether sugar is more dangerous than other sources of energy like starch or fat. In the past health experts suggested people should avoid fat, but more recent research has failed to find serious health problems associated with many types of fat; this led to the promotion of low-carb diets such as Atkins.[3] Today sugar is the media's chief demon, associated with weight gain, diabetes and heart disease.

The moderate argument against sugar is that sugary drinks and snacks contain empty calories, meaning they contain lots of energy which leads to obesity, but have little nutritional value. Hence while they can be eaten in moderation, you will need lots of other more nutritious foods as part of a balanced diet.[4]

Pediatric endocrinologist Robert Lustig has argued that sugar — specifically fructose — is a "toxin" responsible for the high prevalence in Western societies of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, and many cancers. He claims sugars which contain fructose are metabolised differently from starch (which is broken down into glucose): fructose is metabolised by the liver while glucose is used directly by cells all over the body, meaning fructose stresses the liver. In lab rats, high levels of fructose are converted to fat and cause insulin resistance which leads to obesity, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes — this is however only proven in rats.[4] While high glucose levels are regulated by insulin and hunger-suppressant leptin in the human body, fructose does not have the same effect; indeed fructose may raise levels of ghrelin which encourages hunger.[2] High-dose cancer studies of sucrose in mice were negative.[5]

Other scientists contest Lustig's work; John White has pointed out that fructose consumption has actually been falling for the past decade, while obesity is increasing. And most of the research on the dangers of fructose is based on giving huge quantities to rats: as well as other biological differences, rats may metabolise fructose differently to humans. A study by John Sievenpiper found no effect of fructose on body weight, blood pressure, or uric acid levels. A small South African study showed a diet rich in fruit, and hence fructose, did not lead to weight gain.[2] A meta-analysis of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) in children (N=25,745) and adults (N=174,252) found that SSB consumption promoted weight gain.[6]

There are claims that galactose (found in milk) causes premature aging or ovarian cancer; however this is speculative and other studies have found nothing.[7] In particular, a 1990s Australian study found increased ovarian cancer risk was associated with full-fat dairy but not galactose consumption.[8]

Uncontroversially, sugar is also responsible for tooth decay. Aside from that, the science is uncertain so the best advice is probably to eat a balanced diet, avoid excessive amounts of any food, and brush after every meal. Or do what you like and have fun.

Sugar taxes as a tool for reducing consumption[edit]

A sugar tax is a tax on sugar, but typically it is limited to high-sugar foods such as soft drinks. Some countries have implemented or plan to implement such a tax. Others have a fat tax or a tax on high-calorie food, which will penalise sugar, starch, and fat.

Laws[edit]

In the UK, a sugar tax on soft drinks was proposed in the Budget on 16 March 2016. Drinks are divided into tax bands depending on sugar content. Those with between 5g and 8g per 100 ml will pay 18p per litre, and those above 8g will pay a higher rate of 24p per litre.[9]

Denmark had a sugar tax from the 1930s, which was abolished in 2003, along with a fat tax; Norway still has a sugar tax at 7.05 kroner/kg.[10] In 2011, France introduced a tax of 3 to 6 Euro cents per litre.[11]

Mexico has a tax on soft drinks of 10%, equivalent to 1 peso per litre, and an 8% tax on "junk food" or processed food that contains over 275 calories per 100g, both introduced in 2014.[12][13]

The liberal city of Berkeley, California became the first place in the USA to pass a sugar tax in 2014, when it implemented an excise tax of 1 cent per fluid oz (35 cents per litre).[14]

Unfortunately, the tax would only target added sugar in soft drinks, but not added sugar in other places you wouldn't normally expect. In the US, "cake" is routinely misspelled as "bread", with many varieties having sugar as the second most common ingredient. Ideally, the tax would be on the sugar itself, making it more expensive to use in the manufacturing process. In fact, that's exactly what happened; during the 1970's, President Jimmy Carter attempted to nip the obesity problem in the bud then and there by increasing the tariffs on imported sugar.[15] The response by corporations was to instead use totally-not-sugar High Fructose Corn Syrup. In everything. For reference, HFCS is called that specifically to avoid being called sugar, in the same way that companies are currently lobbying Congress to rename HFCS as "corn sugar" to avoid the negative association with fructose.[16] Once we take down HFCS, we can expect to see more things like "evaporated cane juice" in our foods.

Efficacy[edit]

There are three basic measures of efficacy for a sugar tax: price, consumption (or sales), and health effects, but the first two are easier to study.

Most taxes have raised prices somewhat, even if producers have taken some of the hit; in theory increased prices should affect customer behaviour. The Mexican tax on soft drinks reportedly reduced purchases by an average 6% in 2014, with lower-income households cutting purchases by 9%.[17]

Mike Rayner of the University of Oxford has modelled the potential effects in the UK. He estimated that a tax of 20% or 20p per litre would prevent or delay 200,000 cases of obesity.[17] Most sugar taxes have been in place for too little time for any judgement of whether they actually reduce obesity, diabetes, or other health problems.

Criticism[edit]

Liberals (and other groups loosely associated with the left) argue that as low income families tend to buy more sugary products, this tax will only put pressure on their budgets, regardless of health benefits.

Libertarians (and other groups loosely associated with the right) argue that the tax and other regulations are government overreach, interfering with how you want to live your life.

And this is before getting into candy manufacturers themselves complaining about lost profits, though health food producers would likely be in favor for the opposite reason.

Other reduction measures[edit]

A sugar tax is not the only way to reduce sugar consumption. There have been calls for restrictions on the advertising of sugary drinks and snack foods, and for manufacturers to voluntarily cut the amount of sugar in products.[18]

At one point, New York City limited the size of sugar-sweetened drinks to 16 fluid oz. (c.f. Sugary Drinks Portion Cap Rule![]() ), but this regulation was struck down in 2014.

), but this regulation was struck down in 2014.

Big Sugar[edit]

As with tobacco there is a lot of money in sugar production, and the food industry is generally opposed to restrictions on sugar, whether higher taxation, advertising bans, or health warnings on packaging. In 2016, it was revealed that the Sugar Research Foundation (now known as the Sugar Association) "paid nutrition experts from Harvard University to downplay studies linking sugar and heart disease" as part of a coverup of actual adverse health effects. The experts published a 1967 review in the New England Journal of Medicine, which wrongly influenced nutritionists for decades.[19][20]

The Coca-Cola company, one of the world's biggest manufacturers of flavored sugar water, insinuated itself into the Chinese government's anti-obesity campaign, making the focus on exercise to the exclusion diet.[21]

An advertisement from 1970, implying that one could lose weight by eating more sugar[22]

Advertisement from 1977: If sugar is so fattening, how come so many kids are thin?[23]

Other cautions[edit]

The production of cane sugar in the Americas was for a long time done by slaves in the Caribbean and South America. Even today the conditions of sugar workers can be horrible; a 2006 report found workers in the Dominican Republic living in squalid conditions with insufficient food, and with children working in the fields.[24] Luckily, nice Germans bred sugar beet and the Japanese invented high fructose corn syrup, so you can rot your teeth with moral superiority.

And if you want to cut down on sugar, other sweeteners are a whole different minefield.

Non-food uses of sugars[edit]

Sugars are among the most important base chemicals for many industrial processes, most famously the production of alcohol (both for drinking and for other purposes, such as driving Brazilian cars).

References[edit]

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on sugar.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Is Sugar Really Toxic? Sifting through the Evidence, Ferris Jabr, Scientific American, 15 July 2013

- ↑ What If It's All Been A Big Fat Lie?, Gary Taubes, New York Times, 7 July 2002

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Is Sugar Toxic?, Gary Taubes, New York Times, 13 April 2011

- ↑ The Carcinogenic Potency Database: Sucrose (CAS 57-50-1) (archived from April 27, 2017).

- ↑ Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis by V. S. Malik et al. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013 Oct;98(4):1084-102. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.058362. Epub 2013 Aug 21.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Galactose.

- ↑ Webb PM, Bain CJ, Purdie DM, Harvey PW, Green A. Milk consumption, galactose metabolism and ovarian cancer (Australia). Cancer Causes Control. 1998 Dec;9(6):637-44.

- ↑ Sugar tax: How it will work?, Nick Triggle, BBC, 16 March 2016

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on soda tax.

- ↑ France approves fat tax on sugary drinks such as Coca-Cola and Fanta, Daily Mail, 29 Dec 2011

- ↑ Mexico to tackle obesity with taxes on junk food and sugary drinks, The Guardian, 1 November 2013

- ↑ Mexico enacts soda tax in effort to combat world's highest obesity rate, The Guardian, 16 January 2014

- ↑ Nation’s First Soda Tax Passed in California City, Time, 5 Nov 2014

- ↑ Chicago Tribune, Nov 13th 1977

- ↑ HFCS lobby group hopes to change name, Popsugar.com

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Mexican soda tax cuts sales of sugary soft drinks by 6% in first year, Sarah Boseley, The Guardian, 18 June 2015

- ↑ Sugar is as dangerous as alcohol and tobacco, warn health experts, Daily Telegraph, 9 Jan 2014

- ↑ Sugar industry sought to sugarcoat causes of heart disease: Payments revealed to authors of influential 1967 report touting fat and cholesterol as problems by Laura Beil (9:00am, September 25, 2016) Science News.

- ↑ Sugar Industry and Coronary Heart Disease Research: A Historical Analysis of Internal Industry Documents by Christin E. Kearns et al. JAMA Intern. Med. September 12, 2016. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5394.

- ↑ Study: Coca-Cola Shaped China's Efforts To Fight Obesity by Jonathan Lambert (January 10, 201911:56 AM ET) NPR.

- ↑ 8 Insane Vintage Ads That Make Sugar Seem Like A Health Food by Lauren F. Friedman (Oct 29, 2014, 8:50 AM) Business Insider.

- ↑ Bringing disgust in through the backdoor in healthy food promotion: a phenomenological perspective" by Bas de Boer & Mailin Lemke (2021) Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 24:731–743. doi:10.1007/s11019-021-10037-0.

- ↑ Is sugar production modern day slavery?, CNN, 18 Dec 2006

KSF

KSF