Thirty Years War

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 13 min

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 13 min

| Christ died for our articles about Christianity |

| Schismatics |

| Devil's in the details |

“”♫Religion and greed,

♫Cause millions to bleed. ♫Three decades of war! |

| —Sabaton, "A Lifetime of War" |

“”First came the Greycoats to eat all my swine, Next came the Bluecoats to make my sons fight, Next came the Greencoats to make my wife whore, Next came the Browncoats to burn down my home. I have naught but my life, now come the Blackcoats to rob me of that.

|

| — Anonymous poet |

The Thirty Years' War was a massive European religious clusterfuck fought between 1618 and 1648. So it's quite aptly named. It is (and will hopefully remain) the deadliest religious conflict ever to have taken place in Europe,[1] killing somewhere between five and ten million people.[2] It is also the longest continuously fought war in history, squeezing in ahead of other creatively named conflicts like the Hundred Years' War and the Eighty Years War, where the belligerents would occasionally take a coffee break.

Given the nature of politics at the time, the causes of the war are complex, but for the most part, they all stem from the angst which had been slowly building between Protestants and Catholics following the Protestant Reformation. Tensions reached a boiling point when a bunch of rowdy Bohemians tossed some Catholic Hapsburg officials out of a window. From that point on, the Holy Roman Empire (the highly decentralized predecessor state to modern Germany) was sucked into a perfect storm. Previously existing problems, like tensions between the Holy Roman Emperor and his princes, Swedish expansionism, rivalry between France and the Hapsburgs, the ongoing Spanish-Dutch war, and anger over feudalism fed that perfect storm until it became a white-hot lava hurricane which left Central Europe in ruins. The war is also generally infamous for the atrocities committed against civilian peasants, which resulted in deadly famines and plagues.

Of course, the defining question of whether Protestants or Catholics were God's favorite children was answered with a predictable "Ehhhhhhh…"![]()

Origins[edit]

Religious tensions[edit]

By the time the 17th century rolled around the corner, the Holy Roman Empire had long since degraded into a fractured collection of independent duchies, kingdoms, electorates, bishoprics, and archbishoprics. The whole thing looked like nothing so much as vomit on a map.[3] Most of these dukes and princes were independent enough to choose their own religions for their realms to follow, a right which had been explicitly granted to them with the Peace of Augsburg in 1555.[4] That created problems, however, as every instance of disputed succession became a religious crisis resulting in violence, creating incidents like the War of the Jülich Succession.![]() However, the recently-elected Emperor Ferdinand II sought to change this, as he was far more extreme in his Catholic beliefs than most of his predecessors, zealously promoting the Counter-Reformation and coming to the throne pre-packaged with a reputation for oppressing Protestants.[5] With the highly-delicate situation evolving in the German lands, Ferdinand II ended up being exactly the wrong person at the wrong time.

However, the recently-elected Emperor Ferdinand II sought to change this, as he was far more extreme in his Catholic beliefs than most of his predecessors, zealously promoting the Counter-Reformation and coming to the throne pre-packaged with a reputation for oppressing Protestants.[5] With the highly-delicate situation evolving in the German lands, Ferdinand II ended up being exactly the wrong person at the wrong time.

Power of the Hapsburgs[edit]

Despite the title of "Holy Roman Emperor" largely being empty, the House of Hapsburg had become the most dominant political entity in Europe by using the interesting tactic of marrying everything that moved and inheriting all of their shit.[6] By this time, the Hapsburgs controlled large swathes of valuable territory, directly ruling Austria and Bohemia and holding the throne of the Kingdom of Hungary. Meanwhile, another branch of the Hapsburg family held the crown of Spain, which included the Spanish Netherlands, southern Italy, and a vast colonial empire. However, you never get to the top without making enemies, and the Hapsburgs had their fair share, including the Bourbons in France to the west and the Ottomans to the south. These rivals were quite thrilled to have an opportunity to screw Europe's first family (without the marriage thing, obviously).

Side angst[edit]

Along with this stew of awfulness, there was also the Eighty Years' War, which had been raging since 1568, largely concerning the Spanish Netherlands' revolt against Spanish rule. Surprise, surprise, a big cause of the war was Spain's insistence on enforcing Catholicism in the heavily Protestant Dutch provinces. In the background, there was yet another war, this time between Sweden and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth,![]() which became integral to the story of the Thirty Years' War when Sweden invaded the Holy Roman Empire. Denmark and Sweden also hated each other, and they would later go off to fight a separate war

which became integral to the story of the Thirty Years' War when Sweden invaded the Holy Roman Empire. Denmark and Sweden also hated each other, and they would later go off to fight a separate war![]() between 1643 and 1645. Because why the hell not? Lastly, England was largely spared from the war, as while the King wanted to join the fighting, Parliament refused to give him the money to do so, much to his annoyance. Unfortunately for them, the English Civil War broke out between the King (and his supporters) and Parliament (and its supporters), and soon spread to Scotland and Ireland. The war ultimately led to the King's defeat and execution, and his replacement by a military dictatorship.

between 1643 and 1645. Because why the hell not? Lastly, England was largely spared from the war, as while the King wanted to join the fighting, Parliament refused to give him the money to do so, much to his annoyance. Unfortunately for them, the English Civil War broke out between the King (and his supporters) and Parliament (and its supporters), and soon spread to Scotland and Ireland. The war ultimately led to the King's defeat and execution, and his replacement by a military dictatorship.

God's war[edit]

Just to make things a little easier on future historians, God decided to split this war into nice, relatively clean, acts. Keep in mind, this is all happening against a backdrop of near-constant slaughtering in Germany.

The Bohemian Revolt (1618-1625)[edit]

The War proper is considered to have begun with an incident called the Defenestration of Prague,[7] a small bit of unpleasantness kicked off by Ferdinand II sending his goons to shut down Protestant chapels. That's not the kind of stunt you want to pull in one of Empire's most religiously diverse areas. In response, Protestant authorities held an assembly in the city of Prague and held a show trial which convicted the Emperor's men of violating imperial law, following this up by tossing them out of a third-story window (defenestration, noun). Several instances of brinksmanship later, Bohemia had a shiny new Calvinist king and some shiny new allies, and Austria was mobilizing an army to sort everything out before the situation got out of hand.[8] Austria utterly wrecked the Bohemian forces,[9] but the strategic victory and the following executions of Czech aristocrats convinced the other Protestant powers to intervene.

Danish intervention (1625-1630)[edit]

Following a string of Imperial victories in the German lands, Denmark-Norway, under the Lutheran King Christian IV, feared for its own sovereignty and finally joined the war in 1620 to support the Protestant cause, along with financial aid from the French.[10] Thanks to tolls on shipping through the Baltic, Denmark-Norway had become a rich and powerful nation.[10] Meanwhile, Ferdinand recruited Albrecht von Wallenstein, a Bohemian nobleman, to lead an army against the Danes.[11] Christian IV began to employ a bold strategy of losing horribly to Wallenstein's forces whenever they met, eventually being forced to flee to his homeland, losing most of northern Germany in the process.[10] Denmark-Norway was finally forced out of the war, abandoning its support for the Protestant cause. The Holy Roman Empire would need to wait for a different Protestant savior.

Swedish intervention (1630-1635)[edit]

By this point, Imperial forces had a heavy presence in northern Germany, and this threatened yet another Scandinavian power: Sweden. Swedish king Gustav II Adolph, known as Gustavus Adolphus, or the "Lion of the North," entered the war to create an alliance of Protestant German states under his protection.[12] Having been previously embroiled in war against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Swedes were unable to intervene before this until Gustav managed to enlist Russian help in exchange for land.[13] With financial and materiel aid from the French, Sweden invaded the Empire through Pomerania, a duchy on the Baltic coast.

In a daring split from the Danish strategy, Gustavus Adolphus mixed things up a bit by employing the tactic of actually winning for a change, smashing the Catholic forces at the Battle of Breitenfeld,[14] Much of his success can be attributed to his usage of lightweight artillery, which could be towed around the battlefield with relative ease.[15] He also encouraged the usage of lighter weapons, more agile formations, and initiative among junior officers.[16] After several more clashes, all of which ended in Swedish victories, Ferdinand sent Wallenstein back into the fold, resulting in another battle![]() which Gustavus Adolphus won. His victory didn't stop him from being killed in action, however, and without his leadership, Swedish forces quickly folded, and their ability to continue the war became very doubtful. The Protestants had to wait for yet another country to save them.

which Gustavus Adolphus won. His victory didn't stop him from being killed in action, however, and without his leadership, Swedish forces quickly folded, and their ability to continue the war became very doubtful. The Protestants had to wait for yet another country to save them.

French intervention (1635-1648)[edit]

In the previous phases, one may have noticed France's name cropping up every now and then. Indeed, France, despite also being Roman Catholic, viewed the Hapsburgs as a threat due to their enormous power and territorial holdings across France's northern, eastern and southern borders. Dissatisfied with the performance of their proxies, the French joined the war themselves by opening several offensives in the Low Countries.[17] At this point, the war moved away from its origins as a religious conflict and became an extension of France's efforts to contain the influence of the Hapsburgs. With the Swedes reorganized, the war carried on, and the tide slowly turned against the Spaniards, finally culminating in their defeat in the Battle of Rocroi![]() in 1643. At this point, the belligerent powers began to negotiate a peace settlement. Sadly, it took them a long damn time to get around to agreeing on one.

in 1643. At this point, the belligerent powers began to negotiate a peace settlement. Sadly, it took them a long damn time to get around to agreeing on one.

The Peace of Westphalia (1648)[edit]

The Peace of Westphalia is a term which refers to two peace treaties signed in Münster and Osnabrück which formally ended hostilities in the Thirty Years' War.

Immediate effects[edit]

A wide-ranging series of agreements extended to all of the belligerent powers; the treaties of Westphalia mandated a large number of immediate changes to the European power system. They are:

- Confirmation of the Treaty of Augsburg allowing Holy Roman princes to choose the state religion of their own realms.

- Guaranteeing limited rights for religious minorities.[18]

- Spanish recognition of independence for the Netherlands, and Dutch recognition of Spanish ownership of modern-day Belgium. Imperial recognition of Swiss independence.

- General amnesty for everyone who participated in the fighting.[18]

- French annexation of Alsace-Lorraine.[18]

- Alterations to the election procedures in determining future Holy Roman Emperors.

- Sheer destruction in Germany causing the loss of a third of its population. Seriously, prior to World War II, this was the war most Germans associated with apocalyptic destruction.

Long term consequences[edit]

Despite being a dusty old war that no one gives a shit about, the Thirty Years' War created much of the world we know today. With the devastating nature of the war and the revolutionary nature of the peace, long-term effects were numerous and vitally important to European politics.

- Over the next decades and centuries, the experiences of the religious war led to increasing secularization in Europe and the birth of the Enlightenment.[19]

- The unstated acknowledgement of Westphalian sovereignty, the principle of international law that each state de jure has sovereignty over its domestic policies (de facto being another matter). The concept went unchallenged until about the mid-20th century.[20][21]

- In acknowledging religious sovereignty inside the Holy Roman Empire, the Peace of Westphalia finalized its collapse as a single entity. The HRE would be little more than a name on paper until Napoleon finally put it out of its misery in 1806.

- The introduction of limited religious freedom caused the decline of Catholicism in northern Europe and lessening of papal influence on secular affairs.[22]

- France rose to prominence as an economic and military great power, and Sweden as a military great power. Having failed to regain their most productive provinces and enterprises, the Spanish Habsburgs continued to decline.[22]

- The acceleration of feudalism's slow death in Europe.[23]

- The creation of the modern fiscal state and modern banking and the pursuit of overseas colonies and trading outposts by England, The Netherlands, and France to fund warfare. Leading to...

- The birth of capitalism and capitalist morality, including moral justifications of lending with interest (previously usury, a sin).[24]

- French annexation of Alsace-Lorraine would turn into a festering wound of hostility between France and the successive German states up to World War II. The land is currently under French control and, for the first time since the Thirty Years' War, not being disputed between France and Germany.

Atrocities and other fun stuff[edit]

Crimes against humanity[edit]

As one could expect, the Thirty Years' War caused a horrifying number of civilian deaths, particularly due to famine and disease.[25] That being said, the soldiers did a fair amount of killing on their own; the Thirty Years' War is heavily characterized by the barbarity committed against civilian populations, including massacres, looting, mass rape, and desecration of corpses.[26] The conflict also saw an expanded use of mercenary forces by all parties along with a general increase in the average size of their armies. Unfortunately for anyone who wasn't a noble, those armies still lived off the land by raiding farms, stealing livestock, looting villages, and slaughtering anyone who resisted.[27] This happened irrespective of national loyalties or religious faith; soldiers in this war were always the enemy of civilians.[28] With the strict requirements for quartering troops and offering them supplies, even friendly armies would drive the surrounding lands into famine and death. The lofty goals and principles of people like Gustavus Adolphus and Ferdinand II did jack all to affect how the soldiers conducted themselves.

Mercenaries[edit]

The heavy reliance on mercenary forces also had a detrimental effect on the quality of soldiers in general, as mercenary captains would fill out their rosters by levying troops from the civilian population.[29] The Thirty Years' War represented a major step backward in military tactics and professionalism, although this could be a contributing factor to the rise of truly professional fighting forces in the next century. Meanwhile, the moral standards of war were also vastly different from today, with it generally being accepted even among the most liberal theorists that innocent civilians are legitimate targets and that soldiers were entitled to take "spoils" from the populations they victimized.[30] This also led to a widely-held desire to make the war "profitable," for if an army could sustain itself by looting, costs of maintenance would decrease and profit margins would vastly increase. Indeed, Albrecht von Wallenstein, one of the most influential Catholic commanders, made his personal fortune using this exact same theory.[30] By the last phase of the war, it had actually become cheaper to keep fighting, because mercenary companies would charge a severance fee upon being released and then happily join the enemy's side.

Famine and disease[edit]

Because most of the fighting occurred on Holy Roman territory and due to the back-and-forth nature of the war, the same areas were often occupied and re-occupied for decades on end, resulting in completely razed land, thousands of depopulated villages, and desperate shortages of grain and livestock. This, shockingly, led to hideous famines.[30] Being a war conducted before disease was truly understood, the conditions in army camps were almost universally squalid, and soldiers would carry plagues with them wherever they traveled.[30] This is ultimately much of what made the war so lethal. Epidemics ravaged the millions weakened by starvation.

Witch hunts[edit]

“”There are still four hundred in the city, high and low, of every rank and sex — nay, even clerics — so strongly accused that they may be arrested any hour. Some out of all offices and faculties must be executed; clerics, counselors, doctors, city officials and court assessors. There are law students to be arrested. The prince-bishop has over forty students here who are to be pastors; thirteen or fourteen of these are said to be witches. A few days ago a dean was arrested; two others who were summoned have fled. The notary of our church consistory, a very learned man, was yesterday arrested and put to torture. In a word, a third part of the city is involved.

|

| — Chancellor for the bishop of Würzburg, 1629[31] |

Oh, you didn't think we could have an article about the most bullshit religious war in history without bringing witch hunts into it, did you?

Unfortunately, hysteria over the existence of witches was present among both Protestants and Catholics in Europe. Against the backdrop of the war, paranoia of an attack, famine, or epidemic spurred many areas to begin hunting down witches to prevent these calamities.[32] Most of the actual trials and executions occurred in the quieter areas of the war, as everyone else was too busy being slaughtered. The sheer volume of trials and executions marked this period as the absolute height of Europe's witch obsession.[33]

Witch trials targeted intellectuals and individuals society already held in suspicion, and confessions were extracted by means of torture.[31] They also occurred for political reasons, such as in the Bishopric of Würzburg, where the Catholic authorities used them to solidify their own authority through a mass purge.[34] Bamberg was one of the witch hunt capitals of Europe, as there are records for the deaths of almost 900 people, beginning with early victims but spreading to the city's well-to-do and anyone who legally opposed the trials.[35] Ultimately, however, the true motivating factor behind the witch trials was religious competition. As the Reformation kicked into full swing, Catholics and Protestants alike fueled popular fear of witches and terrifyingly persecuted people in order to gain converts and frighten them into sticking around.[36] This is why France and Spain, reliably Catholic nations, rarely saw the witch furor of Germany.[36] Economists Peter Leeson and Jacob Russ of George Mason University in Virginia found a greater historical context, saying,[36]

“The phenomenon we document – using public trials to advertise superior power along some dimension as a competitive strategy – is much broader than the prosecution of witches in early modern Europe. It appears in different forms elsewhere in the world at least as far back as the ninth century, all the way up to the 20th and Stalin’s show trials’ in the Soviet Union.”

Ultimately, Europe's religious wars resulted in around 40,000 deaths due to witch trials.[36]

Belligerents[edit]

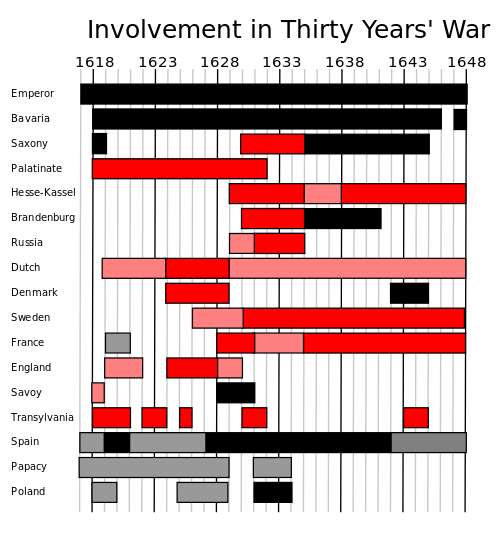

This graph shows the timeline of each nation's involvement in the war. Timelines in red show nations fighting against the Emperor, and timelines in black show nations supporting the Emperor. Note the often changing loyalties.

As the graphic above indicates, the sides were not entirely "Catholic vs. Protestant," contrary to public opinion. While the beginnings of the conflict were indeed mostly religious, the impetus for conflict in later stages was either fear of or support for Habsburg expansion. Post French Wars of Religion (1562-1598) France, which fought on what is commonly called the "Protestant" side, was and is a primarily Catholic nation. As such, the most accurate way to describe each side is pro- or anti-Habsburg.

See also[edit]

- Eighty Years War

- Crusades

- Inquisition

- Syrian Civil War

- Taiping Rebellion

- Lord's Resistance Army

- Massacres in the name of a peaceful faith

References[edit]

- ↑ Peter H. Wilson, Europe's Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years' War (London: Penguin, 2010), 787

- ↑ White, Matthew. "The Thirty Years' War (1618-48)". Necrometrics. ND.

- ↑ A Map of the HRE in 1618. Judge for yourself.

- ↑ The Peace of Ausburg German Culture. ND.

- ↑ Persecutor of the Protestants: Ferdinand II World of the Habsburgs. ND.

- ↑ House of Habsburg Britannica. ND.

- ↑ The Defenestration of Prague Britannica ND.

- ↑ Bohemia Britannica. ND.

- ↑ Battle of White Mountain Erin Naillon, Private Prague Guide Nd.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Lockhart, Paul Douglas (2007). Denmark, 1513–1660: the rise and decline of a Renaissance monarchy. Oxford University Press. p. 166. ISBN 0-19-927121-6. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20080405122000/http://www.prague-guide.co.uk/categories/Attractions%2C-What-to-See/Wallenstein-Palace-Gardens/ Wallenstein Palace Gardens

- ↑ "Lecture 6: Europe in the Age of Religious Wars, 1560–1715". historyguide.org. ND.

- ↑ Dukes, Paul, ed. (1995). Muscovy and Sweden in the Thirty Years' War 1630–1635. Cambridge University Press. p. [page needed]. ISBN 9780521451390.

- ↑ The Battle of Breitenfeld

- ↑ Gustavus Adolphus and His Army

- ↑ Military developments in the Thirty Years' War C N Trueman "Military Developments In The Thirty Years' War" historylearningsite.co.uk. The History Learning Site, 25 Mar 2015.

- ↑ Thion, S. French Armies of the Thirty Years' War (Auzielle: Little Round Top Editions, 2008).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Westphalia, Peace of Bardo Fassbender, Oxford Public International Law, Feb. 2011 (section B10)

- ↑ What was the Enlightenment? LiveScience Jessie Szalay Jul. 7, 2016.

- ↑ Henry Kissinger (2014). "Introduction and Chpt 1". World Order: Reflections on the Character of Nations and the Course of History. Allen Lane. ISBN 0241004268.

- ↑ Fassbender E18.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Consequences and Effects of the Thirty Years' War Nicole Smith, Dec 7, 2011

- ↑ Helmolt, Hans Ferdinand (1903). The World's History: Western Europe to 1800. W. Heinemann. p. 573. ISBN 0-217-96566-0.

- ↑ Graeber, David (2014). Debt: the First 5,000 Years. Melville House. pp.344-347 ISBN 978-1-61219-419-6

- ↑ The Thirty Years' War Produced Astonishing Casualties

- ↑ The Thirty Years' War

- ↑ Military developments in the Thirty Years' War C N Trueman "Military Developments In The Thirty Years' War" historylearningsite.co.uk. The History Learning Site, 25 Mar 2015.

- ↑ De iniustitia belli: Violence Against Civilians in the Thirty Years' War Berg, Joseph, "De iniustitia belli: Violence Against Civilians in the Thirty Years' War" (2016).Honors Thesis. 115. page 9.

- ↑ Geoff Mortimer, Eyewitness Accounts of the Thirty Years' War (Basingstoke, Hampshire: 5 Palgrave, 2002), 29.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 De iniustitia belli: Violence Against Civilians in the Thirty Years' War Berg, Joseph, "De iniustitia belli: Violence Against Civilians in the Thirty Years' War" (2016). Honors Thesis. 115. page 6.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Kors, A.C., Peters, E. (2001). Witchcraft in Europe, 400-1700: A Documentary History. 2nd Edition

- ↑ Witch Trials in the Thirty Years War Bartered History

- ↑ Briggs, Robin: Witches and Neighbors: The Social and Political Context of European Witchcraft Penguin Books, New York 1996

- ↑ Gary F. Jensen (2007). The Path of the Devil: Early Modern Witch Hunts. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742546974. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ Bamberg, Germany: The Early Modern Witch Burning Stronghold Connolly, Sharon Bennet History, the interesting bits 11.03.16

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 Why Europe’s wars of religion put 40,000 ‘witches’ to a terrible death Doward, Jamie. The Guardian. 06.01.18

KSF

KSF