Astrocytoma pathophysiology

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 10 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 10 min

|

Astrocytoma Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Study |

|

Astrocytoma pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Astrocytoma pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Astrocytoma pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Fahimeh Shojaei, M.D., Shivali Marketkar, M.B.B.S. [2], Ammu Susheela, M.D. [3]

Overview[edit | edit source]

The exact pathogenesis of astrocytoma is not completely understood but it is believed that this tumor has a close association with genetic mutations. Microscopic pathologic findings in pilocytic astrocytoma include normal cells with slow growth rate, biphasic pattern (dense fibrillar tissue within loose myxoid tissue), calcification, vascular hyalinization, and nested fibrotic pattern. In diffuse astrocytoma, we may see atypical cells, relatively slow mitosis rate, diffusely infiltrate neuropil and poorly defined cytoplasm. In anaplastic astrocytoma, we may see pleomorphic and malignant cells, high mitosis rate, hyperchromatosis, and prominent small vessels. In glioblastoma multiform, we may see pleomorphic cells, naked nuclei, multi-focal necrosis, pseudopalisading pattern, scattered pyknotic nuclear debris in the center, micro-vascular proliferation, and vascular thrombi.

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

- The exact pathogenesis of astrocytoma is not completely understood but it is believed that this tumor has a close association with genetic mutations.[1]

- The origin of this tumor is from neuroepithelial cells.

Associated conditions[edit | edit source]

- There are no conditions associated with astrocytoma.

Genetics[edit | edit source]

Low-Grade Astrocytomas[edit | edit source]

- Genomic alterations involving BRAF activation are very common in sporadic cases of pilocytic astrocytoma, resulting in activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway.[2][3][4][5]

- BRAF activation in pilocytic astrocytoma occurs most commonly through a KIAA1549-BRAF gene fusion, producing a fusion protein that lacks the BRAF regulatory domain.

- This fusion is seen in most infratentorial and midline pilocytic astrocytomas, but is present at lower frequency in supratentorial (hemispheric) tumors.[6][7][8][9][10]

- Presence of the BRAF-KIAA1549 fusion predicted for better clinical outcome (progression-free survival [PFS] and overall survival) in one report that described children with incompletely resected low-grade gliomas.[11]

- Other factors such as p16 deletion and tumor location may modify the impact of BRAF mutation on outcome.

- Progression to high-grade glioma is rare for pediatric low-grade glioma with the BRAF-KIAA1549 fusion.[12]

- BRAF activation through the KIAA1549-BRAF fusion has also been described in other pediatric low-grade gliomas (e.g.,pilomyxoid astrocytoma).

- Other genomic alterations in pilocytic astrocytomas that may also activate the ERK/MAPK pathway (e.g., alternative BRAF gene fusions, RAF1 rearrangements, RAS mutations, and BRAF V600E point mutations) are less commonly observed.[13]

- BRAF V600E point mutations are observed in nonpilocytic pediatric low-grade gliomas as well, including approximately two-thirds of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma patients and in ganglioglioma and desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma patients.

- A retrospective study of 53 children with gangliogliomas demonstrated BRAF V600E staining in approximately 40% of tumors.

- Five-year recurrence-free survival was worse in the V600E-mutated tumors (about 60%) than in the tumors that did not stain for V600E (about 80%).

- The frequency of the BRAF V600E mutation was significantly higher in pediatric low-grade glioma that transformed to high-grade glioma (8 of 18 cases) compared to the frequency of the mutation in cases that did not transform (10 of 167 cases).[14]

- As expected, given the role of NF1 deficiency in activating the ERK/MAPK pathway, activating BRAF genomic alterations are uncommon in pilocytic astrocytoma associated with NF1.

- Activating mutations in FGFR1 and PTPN11, as well as NTRK2 fusion genes, have also been identified in non-cerebellar pilocytic astrocytomas. In pediatric grade II diffuse astrocytomas, the most common alterations reported are rearrangements in the MYB family of transcription factors in up to 53% of tumors.[15]

High-Grade Astrocytomas[edit | edit source]

- Pediatric high-grade gliomas, especially glioblastoma multiforme, are biologically distinct from those arising in adults.[16][17][18][19]

- Pediatric high-grade gliomas, compared with adult tumors, are more frequently associated with PDGF/PDGFR genomic alterations and mutations in histone H3.3genes and less frequently with PTEN and EGFR genomic alterations.

- Although, it was believed that pediatric glioblastoma multiforme tumors were more closely related to adult secondary glioblastoma multiforme tumors in which there is step-wise transformation from lower-grade into higher-grade gliomas with tumors having IDH1 and IDH2 mutations, the latter mutations are rarely observed in childhood glioblastoma multiforme tumors.[20][21]

- Based on epigenetic patterns (DNA methylation), pediatric glioblastoma multiforme tumors are separated into relatively distinct subgroups with distinctive chromosome copy number gains/losses and gene mutations.[22]

- Two subgroups have identifiable recurrent H3F3A mutations, suggesting disrupted epigenetic regulatory mechanisms, with one subgroup having mutations at K27 (lysine 27) and the other group having mutations at G34 (glycine 34). The subgroups are the following:

- H3F3A mutation at K27: The K27 cluster occurs predominately in mid-childhood (median age, approximately 10 years), is mainly midline (thalamus, brainstem, and spinal cord), and carries a very poor prognosis. These tumors also frequently have TP53 mutations. Thalamic high-grade gliomas in older adolescents and young adults also show a high rate of H3F3A K27 mutations.

- H3F3A mutation at G34: The second H3F3A mutation tumor cluster, the G34 grouping, is found in older children and young adults (median age, 18 years), arises exclusively in the cerebral cortex, and carries a better prognosis. The G34 clusters also have TP53 mutations and widespread hypomethylation across the whole genome.

- The H3F3A K27 and G34 mutations appear to be unique to high-grade gliomas and have not been observed in other pediatric brain tumors.[23] Both mutations induce distinctive DNA methylation patterns compared with the patterns observed in IDH-mutated tumors, which occur in young adults.[24]

- Other pediatric glioblastoma multiforme subgroups include the RTK PDGFRA and mesenchymal clusters, both of which occur over a wide age range, affecting both children and adults.

- The RTK PDGFRA and mesenchymal subtypes are comprised predominantly of cortical tumors, with cerebellar glioblastoma multiforme tumors being rarely observed; they both carry a poor prognosis.

- Childhood secondary high-grade glioma (high-grade glioma that is preceded by a low-grade glioma) is uncommon (2.9% in a study of 886 patients).

- No pediatric low-grade gliomas with the BRAF-KIAA1549 fusion transformed to a high-grade glioma, whereas low-grade gliomas with the BRAF V600E mutations were associated with increased risk of transformation.

- Approximately 40% of patients (7 of 18) with secondary high-grade glioma had BRAF V600E mutations, with CDKN2A alterations present in 57% of cases (8 of 14).

| • Stem cell • Precursor cell • Glial cell | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • IDH1 mutation | • 10q loss • PTEN mutation • EGFR overexpression • MDM2 overexpression | • KIAA1549-BRAF fusion • MAPK/ERK abnormalities | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • p53 mutation • PDGF/PDGFRA overexpression | Primary glioblastoma grade IV | Pilocytic astrocytoma grade I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diffuse astrocytoma grade II | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chr 19q loss | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anaplastic astocytoma grade III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10q loss | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glioblastoma (secondary) grade IV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

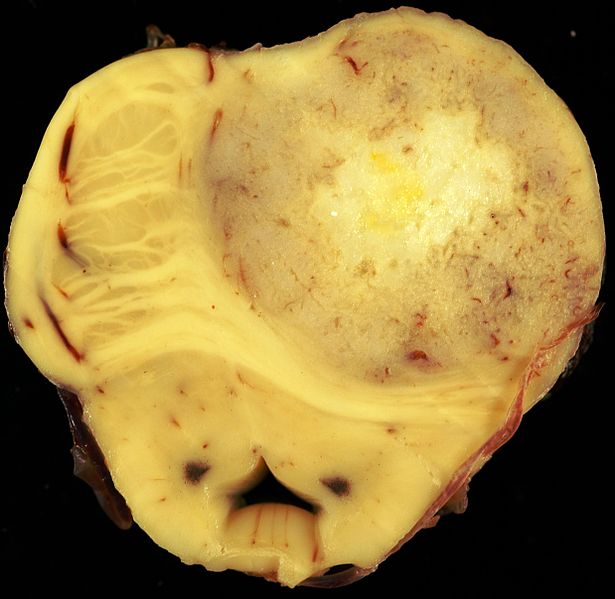

Gross Pathology[edit | edit source]

|

|

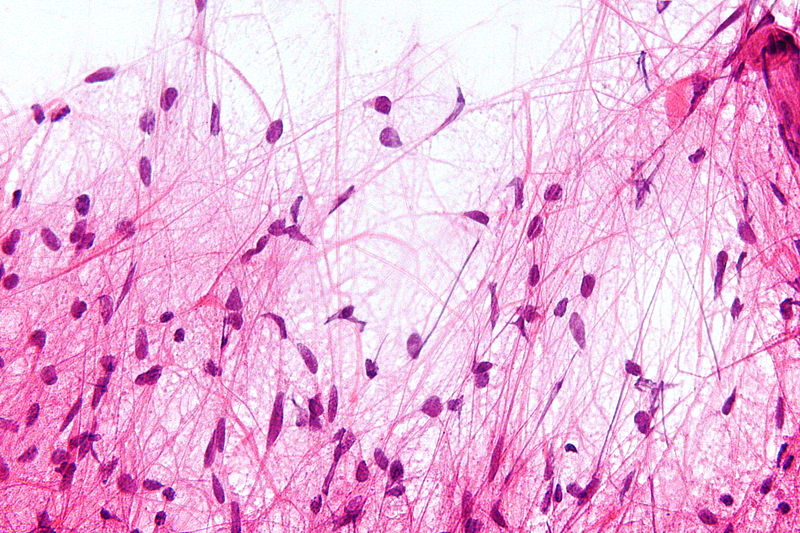

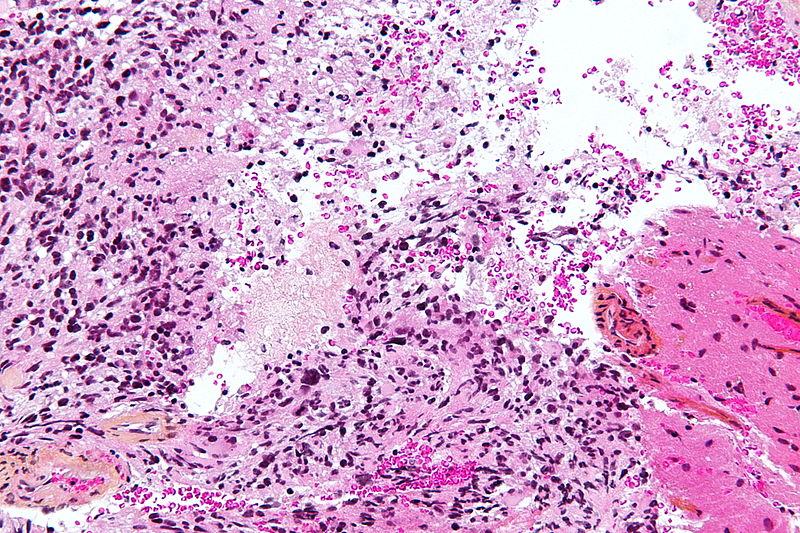

Microscopic Pathology[edit | edit source]

Pathological findings diagnostic of astrocytoma include:[26][27][28][29]

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Histopathological Video[edit | edit source]

Video[edit | edit source]

{{#ev:youtube|O0b4zyDQcyI}}

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Mattle, Heinrich (2017). Fundamentals of neurology : an illustrated guide. Stuttgart New York: Thieme. ISBN 9783131364524.

- ↑ Jones DT, Kocialkowski S, Liu L, Pearson DM, Ichimura K, Collins VP (2009). "Oncogenic RAF1 rearrangement and a novel BRAF mutation as alternatives to KIAA1549:BRAF fusion in activating the MAPK pathway in pilocytic astrocytoma". Oncogene. 28 (20): 2119–23. doi:10.1038/onc.2009.73. PMC 2685777. PMID 19363522.

- ↑ Jones DT, Kocialkowski S, Liu L, Pearson DM, Bäcklund LM, Ichimura K; et al. (2008). "Tandem duplication producing a novel oncogenic BRAF fusion gene defines the majority of pilocytic astrocytomas". Cancer Res. 68 (21): 8673–7. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2097. PMC 2577184. PMID 18974108.

- ↑ Forshew T, Tatevossian RG, Lawson AR, Ma J, Neale G, Ogunkolade BW; et al. (2009). "Activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway: a signature genetic defect in posterior fossa pilocytic astrocytomas". J Pathol. 218 (2): 172–81. doi:10.1002/path.2558. PMID 19373855.

- ↑ Bar EE, Lin A, Tihan T, Burger PC, Eberhart CG (2008). "Frequent gains at chromosome 7q34 involving BRAF in pilocytic astrocytoma". J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 67 (9): 878–87. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181845622. PMID 18716556.

- ↑ Korshunov A, Meyer J, Capper D, Christians A, Remke M, Witt H; et al. (2009). "Combined molecular analysis of BRAF and IDH1 distinguishes pilocytic astrocytoma from diffuse astrocytoma". Acta Neuropathol. 118 (3): 401–5. doi:10.1007/s00401-009-0550-z. PMID 19543740.

- ↑ Horbinski C, Hamilton RL, Nikiforov Y, Pollack IF (2010). "Association of molecular alterations, including BRAF, with biology and outcome in pilocytic astrocytomas". Acta Neuropathol. 119 (5): 641–9. doi:10.1007/s00401-009-0634-9. PMID 20044755.

- ↑ Yu J, Deshmukh H, Gutmann RJ, Emnett RJ, Rodriguez FJ, Watson MA; et al. (2009). "Alterations of BRAF and HIPK2 loci predominate in sporadic pilocytic astrocytoma". Neurology. 73 (19): 1526–31. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c0664a. PMC 2777068. PMID 19794125.

- ↑ Lin A, Rodriguez FJ, Karajannis MA, Williams SC, Legault G, Zagzag D; et al. (2012). "BRAF alterations in primary glial and glioneuronal neoplasms of the central nervous system with identification of 2 novel KIAA1549:BRAF fusion variants". J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 71 (1): 66–72. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e31823f2cb0. PMID 22157620.

- ↑ Hawkins C, Walker E, Mohamed N, Zhang C, Jacob K, Shirinian M; et al. (2011). "BRAF-KIAA1549 fusion predicts better clinical outcome in pediatric low-grade astrocytoma". Clin Cancer Res. 17 (14): 4790–8. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0034. PMID 21610142.

- ↑ Horbinski C, Nikiforova MN, Hagenkord JM, Hamilton RL, Pollack IF (2012). "Interplay among BRAF, p16, p53, and MIB1 in pediatric low-grade gliomas". Neuro Oncol. 14 (6): 777–89. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nos077. PMC 3367847. PMID 22492957.

- ↑ Mistry M, Zhukova N, Merico D, Rakopoulos P, Krishnatry R, Shago M; et al. (2015). "BRAF mutation and CDKN2A deletion define a clinically distinct subgroup of childhood secondary high-grade glioma". J Clin Oncol. 33 (9): 1015–22. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3922. PMC 4356711. PMID 25667294.

- ↑ Janzarik WG, Kratz CP, Loges NT, Olbrich H, Klein C, Schäfer T; et al. (2007). "Further evidence for a somatic KRAS mutation in a pilocytic astrocytoma". Neuropediatrics. 38 (2): 61–3. doi:10.1055/s-2007-984451. PMID 17712732.

- ↑ Dahiya S, Haydon DH, Alvarado D, Gurnett CA, Gutmann DH, Leonard JR (2013). "BRAF(V600E) mutation is a negative prognosticator in pediatric ganglioglioma". Acta Neuropathol. 125 (6): 901–10. doi:10.1007/s00401-013-1120-y. PMID 23609006.

- ↑ Zhang J, Wu G, Miller CP, Tatevossian RG, Dalton JD, Tang B; et al. (2013). "Whole-genome sequencing identifies genetic alterations in pediatric low-grade gliomas". Nat Genet. 45 (6): 602–12. doi:10.1038/ng.2611. PMC 3727232. PMID 23583981.

- ↑ Paugh BS, Qu C, Jones C, Liu Z, Adamowicz-Brice M, Zhang J; et al. (2010). "Integrated molecular genetic profiling of pediatric high-grade gliomas reveals key differences with the adult disease". J Clin Oncol. 28 (18): 3061–8. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7252. PMC 2903336. PMID 20479398.

- ↑ Bax DA, Mackay A, Little SE, Carvalho D, Viana-Pereira M, Tamber N; et al. (2010). "A distinct spectrum of copy number aberrations in pediatric high-grade gliomas". Clin Cancer Res. 16 (13): 3368–77. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0438. PMC 2896553. PMID 20570930.

- ↑ Ward SJ, Karakoula K, Phipps KP, Harkness W, Hayward R, Thompson D; et al. (2010). "Cytogenetic analysis of paediatric astrocytoma using comparative genomic hybridisation and fluorescence in-situ hybridisation". J Neurooncol. 98 (3): 305–18. doi:10.1007/s11060-009-0081-4. PMID 20052518.

- ↑ Pollack IF, Hamilton RL, Sobol RW, Nikiforova MN, Lyons-Weiler MA, LaFramboise WA; et al. (2011). "IDH1 mutations are common in malignant gliomas arising in adolescents: a report from the Children's Oncology Group". Childs Nerv Syst. 27 (1): 87–94. doi:10.1007/s00381-010-1264-1. PMC 3014378. PMID 20725730.

- ↑ Schwartzentruber J, Korshunov A, Liu XY, Jones DT, Pfaff E, Jacob K; et al. (2012). "Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma". Nature. 482 (7384): 226–31. doi:10.1038/nature10833. PMID 22286061.

- ↑ Wu G, Broniscer A, McEachron TA, Lu C, Paugh BS, Becksfort J; et al. (2012). "Somatic histone H3 alterations in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas and non-brainstem glioblastomas". Nat Genet. 44 (3): 251–3. doi:10.1038/ng.1102. PMC 3288377. PMID 22286216.

- ↑ Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, Khuong-Quang DA, Jones DT, Konermann C; et al. (2012). "Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma". Cancer Cell. 22 (4): 425–37. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.024. PMID 23079654.

- ↑ Gielen GH, Gessi M, Hammes J, Kramm CM, Waha A, Pietsch T (2013). "H3F3A K27M mutation in pediatric CNS tumors: a marker for diffuse high-grade astrocytomas". Am J Clin Pathol. 139 (3): 345–9. doi:10.1309/AJCPABOHBC33FVMO. PMID 23429371.

- ↑ Khuong-Quang DA, Buczkowicz P, Rakopoulos P, Liu XY, Fontebasso AM, Bouffet E; et al. (2012). "K27M mutation in histone H3.3 defines clinically and biologically distinct subgroups of pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas". Acta Neuropathol. 124 (3): 439–47. doi:10.1007/s00401-012-0998-0. PMC 3422615. PMID 22661320.

- ↑ "National Caner Institute Astrocytoma".

- ↑ Mattle, Heinrich (2017). Fundamentals of neurology : an illustrated guide. Stuttgart New York: Thieme. ISBN 9783131364524.

- ↑ Nafussi, Awatif (2005). Tumor diagnosis : practical approach and pattern analysis. London New York: Arnold Distributed in the U.S.A. by Oxford University Press. ISBN 0340809442.

- ↑ Schniederjan, Matthew (2011). Biopsy interpretation of the central nervous system. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health. ISBN 9780781799935.

- ↑ Mattle, Heinrich (2017). Fundamentals of neurology : an illustrated guide. Stuttgart New York: Thieme. ISBN 9783131364524.

KSF

KSF