Autism (incidence)

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 6 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 6 min

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [4]

Overview[edit | edit source]

The reported incidence of autism varies considerably among countries and is complicated by varying criteria for diagnosing autism, different standards for reporting public health problems, and other possible variations.

Background[edit | edit source]

Autism was first characterised in 1943 by psychiatrist Dr. Leo Kanner of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, and almost simultaneously, in German, by Dr Hans Asperger. Both published case series of children with strikingly similar features.

The number of children born in each year diagnosed with autism in countries reporting figures is larger now than then. The populations of those countries have also increased but it is unclear what change in the incidence fraction has occurred. Public health organizations and researchers are not yet confident they have completely determined causes for all changes in the rate of reports of Autism (vide infra). Potential factors listed by the UK National Autistic Society include:[1]

- The underlying condition may have a changing incidence with time, i.e., more children (and/or more per thousand born) are affected by it;

- More complete pickup of autism (case finding), as a result of increased awareness and funding;

- Attempts in the US and UK to sue vaccine companies may have also increased case-reporting.

- The diagnosis being applied more broadly than before, as a result of the changing definition of the disorder, particularly changes in DSM-III-R;[2] and DSM-IV[3]

- Successively earlier diagnosis in each succeeding cohort of children including recognition in nursery (preschool) - this would affect apparent prevalence but not incidence

There has been public concern that the MMR vaccine or the vaccine preservative thiomersal have contributed to an increase in the incidence of autism; the consensus of the medical and scientific community is that there is no scientific evidence to support these hypotheses,[4] but decreasing uptake of vaccines has led to outbreaks of serious childhood diseases.[5]

Incidence[edit | edit source]

The incidence of a condition is the rate at which new cases occur in a population during a specified interval, e.g. "10 per year" or "12 in 1982". The prevalence of a condition is the proportion of a population that are cases at a point in time, e.g. "1 in 1000".[6]

Examples of the way information is collected to specifically measure incidence rather than prevalence include:

- Annual and age specific incidence for first recorded diagnoses of autism (that is, when the diagnosis of autism was first recorded);

- Annual, birth cohort specific risk of autism diagnosed[7]

Incidence in sub-groups[edit | edit source]

There have been suggestions that the incidence of autism may vary amongst particular groups defined by occupation, lifestyle or genetic isolation. Changes that made travel and communication easier, and the growth of the technological industries during the past decade, have been suggested as means for increase in the proportion of couples likely to produce an autistic child. None of these have been established.[8][9][10][11]

Geographical incidence[edit | edit source]

Denmark[edit | edit source]

In November 2002, a study reported a lower incidence of autism in Denmark than in the US and other countries. An incidence of 1 in 727 (738 out of 537,303) was reported, compared with up to 1 in 86 among primary school children in the United Kingdom and around 1 in 150 children in the USA. Danish authorities also reported a continued increase in the incidence of autism after 1992 after withdrawal of thiomersal-containing vaccines.[12] Data presented in 2003 shows a clear increase in incidence between 1990 and 1995 (before the criteria changed). Thus, the increased incidence of autism after the removal of thiomersal was not a measurement artefact.[13]

Japan[edit | edit source]

The Yokohama study in Japan (2005) examined the incidence of autism before and after the 1993 withdrawal of MMR, reporting 48 and 86 cases per 10,000 children in two sequential years before withdrawal, doubling to 97 and 161 per 10,000 afterwards in the two years afterwards.[14][15]

It studied over 30,000 children (278 cases) born in one district of Yokohama.[16]

United Kingdom[edit | edit source]

The National Autistic Society regarded the incidence and changes in incidence with time as unclear.[17] A 2001 review,[18] by the Medical Research Council, yielded an estimate of one in 166 in children under eight.

The reported autism incidence in the UK rose starting before the first introduction of the MMR vaccine in 1989.[19]

United States[edit | edit source]

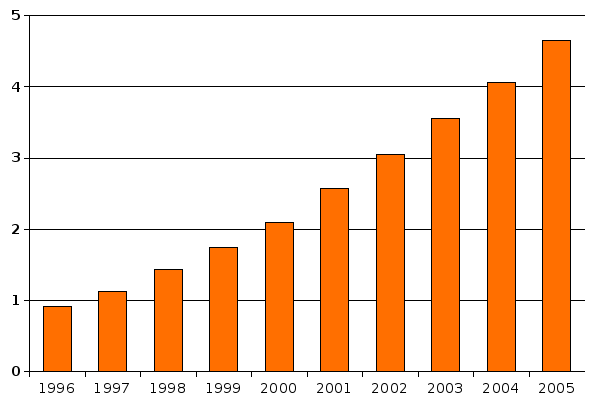

The number of diagnosed cases of autism grew dramatically in the U.S. in the 1990s and early 2000s. For example, in 1996, 21,669 children and students aged 6–11 years diagnosed with autism were served under Part B of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in the U.S. and outlying areas; by 2001 this number had risen to 64,094, and by 2005 to 110,529.[20]

Notes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Incidence National Autistic Society

- ↑ [http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/abstract/145/11/1404 DSM3 changes

- ↑ DSM4 changes

- ↑ Doja A, Roberts W (2006). "Immunizations and autism: a review of the literature". Can J Neurol Sci. 33 (4): 341–6. PMID 17168158.

- ↑ Rose D (2007-08-31). "Vaccine warning as measles cases triple". The Times. Retrieved 2007-09-06. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ British Medical Journal: Epidemiology for the Uninitiated 4th Ed: Quantifying diseases in populations BMJ

- ↑ Kaye JA, del Mar Melero-Montes M, Jick H (2001). "Mumps, measles, and rubella vaccine and the incidence of autism recorded by general practitioners: a time trend analysis". BMJ. 322 (7284): 460–3. PMID 11222420.

- ↑ Parental type

- ↑ BBC report Simon Baron-Cohen believes that "it has become easier for systemizers to meet each other, with the advent of international conferences, greater job opportunities and more women working in these fields."

- ↑ [1] Assortative mating has not been demonstrated in humans. The spouses of identical twins tended to find the other twin annoying rather than attractive.

- ↑ Mearns, Int. Paed. autistic individuals have a higher proportion of engineers as close family members than the rest of the population. Speculation on job choice and phenotype.

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Anne-Marie Plesner, Peter H. Andersen and Preben B. Mortensen Kreesten M. Madsen, Marlene B. Lauritsen, Carsten B. Pedersen, Poul Thorsen. Thimerosal and the Occurrence of Autism: Negative Ecological Evidence From Danish Population-Based Data. Pediatrics 2003;112;604-606. PMID 12949291

- ↑ Hideo Honda, Yasuo Shimizu and Michael Rutter (2005). "No effect of MMR withdrawal on the incidence of autism: a total population study". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 46 (6): 572. PMID 15877763 doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01425.x.

- ↑ Bandolier: incidence around 1993 http://www.jr2.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/booth/Vaccines/noMMR.html

- ↑ Cited in New Scientist[3] and reviewed in Bandolier with graph of main results.

- ↑ http://www.autism.org.uk/nas/jsp/polopoly.jsp?d=459&a=5576 Position statement, official website of National Autistic Society (UK) viewed March 2007

- ↑ http://www.mrc.ac.uk/OurResearch/ResearchFocus/Autism/ResearchStrategy/index.htm

- ↑ Kaye JA, del Mar Melero-Montes M, Jick H (2001). "Mumps, measles, and rubella vaccine and the incidence of autism recorded by general practitioners: a time trend analysis". BMJ. 322 (7284): 460–3. PMID 11222420.

- ↑ "Children and students served under IDEA, Part B, in the U.S. and outlying areas by age group, year and disability category: fall 1996 through fall 2005". U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs. 2006. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

37. Tebruegge M, Nandini V, Ritchie J. Does routine child health surveillance contribute to the early detection of children with pervasive developmental disorders? An epidemiological study in Kent, U.K. BMC Pediatr. 2004 Mar 3;4:4.

References[edit | edit source]

- CPA-APC.org - Diagnosis and Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders Lee Tidmarsh, MD, Fred R Volkmar, MD, The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, Vol 48 pp 517–525, 2003

- NIH.gov - 'The changing prevalence of autism in California', L.A. Croen, J.K. Grether, J Hoogstrate, S Selvin, Journal of Autism Developmental Disorders Vol 32, No 3, pp 207-15, June, 2002

- NIH.gov -'The epidemiology of autistic spectrum disorders: is the prevalence rising?', Lorna Wing, D. Potter, Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev, Vol 8, No 3, pp 151-61, 2002

- NIH.gov - 'The incidence of autism in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976-1997: results from a population-based study', W.J. Barbaresi, S.K Katusic, R.C. Colligan, A.L. Weaver, S.J. Jacobsen, Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, Vol 159, No 1, pp 37-44, January, 2005

- California DDS figures and reports: http://www.dds.ca.gov/FactsStats/quarterly.cfm , http://www.dds.ca.gov/autism/autism_main.cfm

Template:Pervasive developmental disorders

KSF

KSF