Autism epidemiology

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 13 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 13 min

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

[edit | edit source]The epidemiology of autism is the study of factors affecting autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Most recent reviews estimate a prevalence of one to two cases per 1,000 people for autism, and about six per 1,000 for ASD;[1] because of inadequate data, these numbers may underestimate ASD's true prevalence.[2] ASD averages a 4.3:1 male-to-female ratio. The number of children known to have autism has increased dramatically since the 1980s, at least partly due to changes in diagnostic practice; the question of whether actual prevalence has increased is unresolved,[1] and as-yet-unidentified contributing environmental risk factors cannot be ruled out.[3] The risk of autism is associated with several prenatal and perinatal factors, including advanced parental age and low birth weight.[4] ASD is associated with several genetic disorders[5] and with epilepsy,[6] and autism is associated with mental retardation.[7]

Autism and its causes

[edit | edit source]Autism is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder. Many causes have been proposed, but its theory of causation is still incomplete.[8] Autism is largely inherited, although the genetics of autism are complex and it is generally unclear which genes are responsible.[9] Although a link between autism and environmental exposures is plausible, little evidence exists to support associations with specific environmental exposures.[1] In rare cases, autism is strongly associated with agents that cause birth defects.[10] Other proposed causes, such as childhood vaccines, are controversial and the vaccine hypotheses lack convincing scientific evidence.[3]

Frequency

[edit | edit source]Although incidence rates measure autism risk directly, most epidemiological studies report other frequency measures, typically point or period prevalence, or sometimes cumulative incidence. Attention is focused mostly on whether prevalence is increasing with time.[1]

Incidence and prevalence

[edit | edit source]Epidemiology defines several measures of the frequency of occurrence of a disease or condition:[11]

- The incidence rate of a condition is the rate at which new cases occurred per person-year, for example, "2 new cases per 1,000 person-years".

- The cumulative incidence is the proportion of a population that became new cases within a specified time period, for example, "1.5 per 1,000 people became new cases during 2006".

- The point prevalence of a condition is the proportion of a population that had the condition at a single point in time, for example, "10 cases per 1,000 people at the start of 2006".

- The period prevalence is the proportion that had the condition at any time within a stated period, for example, "15 per 1,000 people had cases during 2006".

When studying how diseases are caused, incidence rates are the most appropriate measure of disease frequency as they assess risk directly. However, incidence can be difficult to measure with rarer chronic diseases such as autism.[11] In autism epidemiology, point or period prevalence is more useful than incidence, as the disorder starts long before it is diagnosed, and the gap between initiation and diagnosis is influenced by many factors unrelated to risk. Research focuses mostly on whether point or period prevalence is increasing with time; cumulative incidence is sometimes used in studies of birth cohorts.[1]

Frequency estimates

[edit | edit source]Estimates of the prevalence of autism vary widely depending on diagnostic criteria, age of children screened, and geographical location.[12] Most recent reviews tend to estimate a prevalence of 1–2 per 1,000 for autism and close to 6 per 1,000 for ASD;[1] PDD-NOS is the vast majority of ASD, Asperger's is about 0.3 per 1,000 and the atypical forms childhood disintegrative disorder and Rett syndrome are much rarer.[13] A 2006 study of nearly 57,000 British nine- and ten-year-olds reported a prevalence of 3.89 per 1,000 for autism and 11.61 per 1,000 for ASD; these higher figures could be associated with broadening diagnostic criteria.[14] Studies based on more-detailed information, such as direct observation rather than examination of medical records, identify higher prevalence; this suggests that published figures may underestimate ASD's true prevalence.[2]

Changes with time

[edit | edit source]Attention has been focused on whether the prevalence of autism is increasing with time. Earlier prevalence estimates were lower, centering at about 0.5 per 1,000 for autism during the 1960s and 1970s and about 1 per 1,000 in the 1980s, as opposed to today's 1–2 per 1,000.[1]

The number of reported cases of autism increased dramatically in the 1990s and early 2000s, prompting investigations into several potential reasons:[16]

- More children may have autism; that is, the true frequency of autism may have increased.

- There may be more complete pickup of autism (case finding), as a result of increased awareness and funding. For example, attempts to sue vaccine companies may have increased case-reporting.

- The diagnosis may be applied more broadly than before, as a result of the changing definition of the disorder, particularly changes in DSM-III-R and DSM-IV.

- Successively earlier diagnosis in each succeeding cohort of children, including recognition in nursery (preschool), may have affected apparent prevalence but not incidence.

The reported increase is largely attributable to changes in diagnostic practices, referral patterns, availability of services, age at diagnosis, and public awareness.[1][3][15] A widely cited 2002 pilot study concluded that the observed increase in autism in California cannot be explained by changes in diagnostic criteria,[17] but a 2006 analysis found that special education data poorly measured prevalence because so many cases were undiagnosed, and that the 1994–2003 U.S. increase was associated with declines in other diagnostic categories, indicating that diagnostic substitution had occurred.[18] A 2007 study that modeled autism incidence found that broadened diagnostic criteria, diagnosis at a younger age, and improved efficiency of case ascertainment, can produce an increase in the frequency of autism ranging up to 29-fold depending on the frequency measure, suggesting that methodological factors may explain the observed increases in autism over time.[19] A small 2008 study found that a significant number of people diagnosed with language impairments as children in previous decades would now be given a diagnosis as autism.[20]

Several contributing environmental risk factors have been proposed to support the hypothesis that the actual frequency of autism has increased. These include certain foods, infectious disease, pesticides, MMR vaccine, and vaccines containing the preservative thiomersal, formerly used in several childhood vaccines in the U.S.[1] Although there is overwhelming scientific evidence against the MMR hypothesis and no convincing evidence for the thiomersal hypothesis, other as-yet-unidentified contributing environmental risk factors cannot be ruled out.[3] Although it is unknown whether autism's frequency has increased, any such increase would suggest directing more attention and funding toward changing environmental factors instead of continuing to focus on genetics.[21]

Geographical frequency

[edit | edit source]Australia

[edit | edit source]A 2008 Australian study reported wide variation and inconsistent results in prevalence estimates; for example, national estimates for the prevalence of ASD in Australia ranged from 1.21 to 3.57 per 1,000 for children aged 6–12 years. The study concluded that the prevalence of ASD in Australian children cannot be estimated accurately from existing data.[22]

China

[edit | edit source]A 2008 Hong Kong study reported an ASD incidence rate similar to those reported in Australia and North America, and lower than Europeans. It also reported a prevalence of 1.68 per 1,000 for children under 15 years.[23]

Denmark

[edit | edit source]A 2003 study reported that the cumulative incidence of autism in Denmark began a steep increase starting around 1990, and continued to grow until 2000, despite the withdrawal of thiomersal-containing vaccines in 1992. For example, for children aged 2–4 years, the cumulative incidence was about 0.5 new cases per 10,000 children in 1990 and about 4.5 new cases per 10,000 children in 2000.[24]

Germany

[edit | edit source]A 2008 study found that inpatient admission rates for children with ASD increased 30% from 2000 to 2005, with the largest rise between 2000 and 2001 and a decline between 2001 and 2003. Inpatient rates for all mental disorders also rose for ages up to 15 years, so that the ratio of ASD to all admissions rose from 1.3% to 1.4%.[25]

Japan

[edit | edit source]A 2005 study of a part of Yokohama with a stable population of about 300,000 reported a cumulative incidence to age 7 years of 48 cases of ASD per 10,000 children in 1989, and 86 in 1990. After the vaccination rate of MMR vaccine dropped to near zero, the incidence rate grew to 97 and 161 cases per 10,000 children in 1993 and 1994, respectively, indicating that MMR vaccine did not cause autism.[26]

United Kingdom

[edit | edit source]The incidence and changes in incidence with time are unclear in the UK.[27] The reported autism incidence in the UK rose starting before the first introduction of the MMR vaccine in 1989.[28] A 2004 study found that the reported incidence of pervasive developmental disorders in a general practice research database in England and Wales grew steadily during 1988–2001 from 0.11 to 2.98 per 10,000 person-years, and concluded that much of this increase may be due to changes in diagnostic practice.[29]

United States

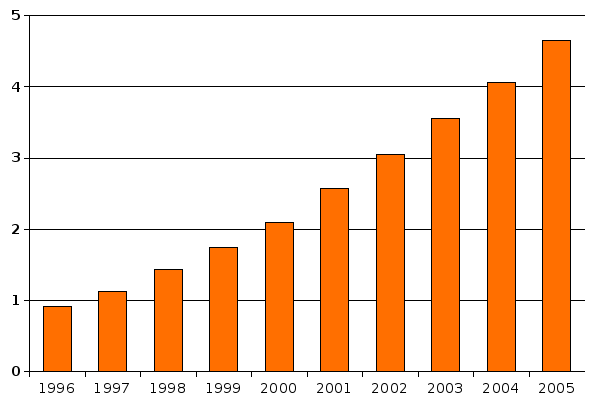

[edit | edit source]The number of diagnosed cases of autism grew dramatically in the U.S. in the 1990s and early 2000s. For example, in 1996, 21,669 children and students aged 6–11 years diagnosed with autism were served under Part B of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in the U.S. and outlying areas; by 2001 this number had risen to 64,094, and by 2005 to 110,529.[30] These numbers measure what is sometimes called "administrative prevalence", that is, the number of known cases per unit of population, as opposed to the true number of cases.[18]

A population-based study of one Minnesota county found that the cumulative incidence of autism grew eightfold from the 1980–83 period to the 1995–97 period. The increase occurred after the introduction of broader, more-precise diagnostic criteria, increased service availability, and increased awareness of autism.[31]

Venezuela

[edit | edit source]A 2008 study reported a prevalence of 1.1 per 1000 for autism and 1.7 per 1000 for ASD.[32]

Genetics

[edit | edit source]As late as the mid-1970s there was little evidence of a genetic role in autism; evidence from genetic epidemiology studies now suggests that it is one of the most heritable of all psychiatric conditions.[33] The first studies of twins estimated heritability to be more than 90%; in other words, that genetics explains more than 90% of autism cases.[9] When only one identical twin is autistic, the other often has learning or social disabilities. For adult siblings, the risk of having one or more features of the broader autism phenotype might be as high as 30%,[34] much higher than the risk in controls.[35] About 10–15% of autism cases have an identifiable Mendelian (single-gene) condition, chromosome abnormality, or other genetic syndrome,[34] and ASD is associated with several genetic disorders.[5]

Since heritability is less than 100% and symptoms vary markedly among identical twins with autism, environmental factors are most likely a significant cause as well. If some of the risk is due to gene-environment interaction the 90% heritability estimate may be too high;[1] new twin data and models with structural genetic variation are needed.[36]

Genetic linkage analysis has been inconclusive; many association analyses have had inadequate power.[36] Studies have examined more than 100 candidate genes; many genes must be examined because more than a third of genes are expressed in the brain and there are few clues on which are relevant to autism.[1]

Risk factors

[edit | edit source]Boys are at higher risk for autism than girls. The ASD sex ratio averages 4.3:1 and is greatly modified by cognitive impairment: it may be close to 2:1 with mental retardation and more than 5.5:1 without. Recent studies have found no association with socioeconomic status, and have reported inconsistent results about associations with race or ethnicity.[1]

The risk of autism is associated with several prenatal and perinatal risk factors. A 2007 review of risk factors found associated parental characteristics that included advanced maternal age, advanced paternal age, and maternal place of birth outside Europe or North America, and also found associated obstetric conditions that included low birth weight and gestation duration, and hypoxia during childbirth.[4]

A large 2008 population study of Swedish parents of children with autism found that the parents were more likely to have been hospitalized for a mental disorder, that schizophrenia was more common among the mothers and fathers, and that depression and personality disorders were more common among the mothers.[37]

Comorbid conditions

[edit | edit source]Autism is associated with mental retardation: a 2001 British study of 26 autistic children found about 30% with intelligence in the normal range (IQ above 70), 50% with mild to moderate retardation, and about 20% with severe to profound retardation (IQ below 35). For ASD other than autism the association is much weaker: the same study reported about 94% of 65 children with PDD-NOS or Asperger's had normal intelligence.[7] ASD is also associated with epilepsy, with variations in risk of epilepsy due to age, cognitive level, and type of language disorder; 5–38% of children with autism have comorbid epilepsy, and only 16% of these have remission in adulthood.[6] Several metabolic defects, such as phenylketonuria, are also associated with autistic symptoms.[38] Phobias, depression and other psychopathological disorders have often been described along with ASD but this has not been assessed systematically.[39]

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Newschaffer CJ, Croen LA, Daniels J; et al. (2007). "The epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders". Annu Rev Public Health. 28: 235–58. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144007. PMID 17367287.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Caronna EB, Milunsky JM, Tager-Flusberg H (2008). "Autism spectrum disorders: clinical and research frontiers". Arch Dis Child. 93 (6): 518–23. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.115337. PMID 18305076.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Rutter M (2005). "Incidence of autism spectrum disorders: changes over time and their meaning". Acta Paediatr. 94 (1): 2–15. PMID 15858952.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kolevzon A, Gross R, Reichenberg A (2007). "Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for autism". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 161 (4): 326–33. doi:10.1001/archpedi.161.4.326. PMID 17404128.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Zafeiriou DI, Ververi A, Vargiami E (2007). "Childhood autism and associated comorbidities". Brain Dev. 29 (5): 257–72. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2006.09.003. PMID 17084999.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Levisohn PM (2007). "The autism-epilepsy connection". Epilepsia. 48 (Suppl 9): 33–5. PMID 18047599.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Chakrabarti S, Fombonne E (2001). "Pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children". JAMA. 285 (24): 3093–9. doi:10.1001/jama.285.24.3093. PMID 11427137.

- ↑ Trottier G, Srivastava L, Walker CD (1999). "Etiology of infantile autism: a review of recent advances in genetic and neurobiological research". J Psychiatry Neurosci. 24 (2): 103–15. PMID 10212552.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Freitag CM (2007). "The genetics of autistic disorders and its clinical relevance: a review of the literature". Mol Psychiatry. 12 (1): 2–22. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001896. PMID 17033636.

- ↑ Arndt TL, Stodgell CJ, Rodier PM (2005). "The teratology of autism". Int J Dev Neurosci. 23 (2–3): 189–99. doi:10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.11.001. PMID 15749245.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Coggon D, Rose G, Barker DJP (1997). "Quantifying diseases in populations". Epidemiology for the Uninitiated (4th edition ed.). BMJ. ISBN 0727911023.

- ↑ Williams JG, Higgins JPT, Brayne CEG (2006). "Systematic review of prevalence studies of autism spectrum disorders". Arch Dis Child. 91 (1): 8–15. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.062083. PMID 15863467.

- ↑ Fombonne E (2005). "Epidemiology of autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders". J Clin Psychiatry. 66 (Suppl 10): 3–8. PMID 16401144.

- ↑ Baird G, Simonoff E, Pickles A; et al. (2006). "Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP)". Lancet. 368 (9531): 210–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69041-7. PMID 16844490.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Prevalence and changes in diagnostic practice:

- Fombonne E (2003). "The prevalence of autism". JAMA. 289 (1): 87–9. doi:10.1001/jama.289.1.87. PMID 12503982.

- Wing L, Potter D (2002). "The epidemiology of autistic spectrum disorders: is the prevalence rising?". Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 8 (3): 151–61. doi:10.1002/mrdd.10029. PMID 12216059.

- ↑ Wing L, Potter D (1999). "Notes on the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders". National Autistic Society. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ↑ Template:Cite paper

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Shattuck PT (2006). "The contribution of diagnostic substitution to the growing administrative prevalence of autism in US special education". Pediatrics. 117 (4): 1028–37. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1516. PMID 16585296. Lay summary (2006-04-03).

- ↑ Wazana A, Bresnahan M, Kline J (2007). "The autism epidemic: fact or artifact?". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 46 (6): 721–30. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e31804a7f3b. PMID 17513984.

- ↑ Bishop DVM, Whitehouse AJO, Watt HJ, Line EA (2008). "Autism and diagnostic substitution: evidence from a study of adults with a history of developmental language disorder". Dev Med Child Neurol. 50 (5): 341–5. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.02057.x. PMID 18384386.

- ↑ Szpir M (2006). "Tracing the origins of autism: a spectrum of new studies". Environ Health Perspect. 114 (7): A412–8. PMID 16835042.

- ↑ Williams K, Macdermott S, Ridley G, Glasson EJ, Wray JA (2008). "The prevalence of autism in Australia. Can it be established from existing data?". J Paediatr Child Health. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2008.01331.x. PMID 18564076.

- ↑ Wong VCN, Hui SLH (2008). "Epidemiological study of autism spectrum disorder in China". J Child Neurol. 23 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1177/0883073807308702. PMID 18160559.

- ↑ Madsen KM, Lauritsen MB, Pedersen CB; et al. (2003). "Thimerosal and the occurrence of autism: negative ecological evidence from Danish population-based data". Pediatrics. 112 (3): 604–6. doi:10.1542/peds.112.3.604. PMID 12949291.

- ↑ Bölte S, Poustka F, Holtmann M (2008). "Trends in autism spectrum disorder referrals". Epidemiology. 19 (3): 519–20. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816a9e13. PMID 18414094.

- ↑ Honda H, Shimizu Y, Rutter M (2005). "No effect of MMR withdrawal on the incidence of autism: a total population study". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 46 (6): 572–9. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01425.x. PMID 15877763. Lay summary – Bandolier (2005).

- ↑ "Incidence of autism". National Autistic Society. 2004. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ↑ Kaye JA, del Mar Melero-Montes M, Jick H (2001). "Mumps, measles, and rubella vaccine and the incidence of autism recorded by general practitioners: a time trend analysis". BMJ. 322 (7284): 460–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7284.460. PMID 11222420.

- ↑ Smeeth L, Cook C, Fombonne E; et al. (2004). "Rate of first recorded diagnosis of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders in United Kingdom general practice, 1988 to 2001". BMC Med. 2: 39. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-2-39. PMID 15535890.

- ↑ "Children and students served under IDEA, Part B, in the U.S. and outlying areas by age group, year and disability category: fall 1996 through fall 2005". U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs. 2006. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ↑ Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Jacobsen SJ (2005). "The incidence of autism in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976-1997: results from a population-based study". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 159 (1): 37–44. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.1.37. PMID 15630056.

- ↑ Montiel-Nava C, Peña JA (2008). "Epidemiological findings of pervasive developmental disorders in a Venezuelan study". Autism. 12 (2): 191–202. doi:10.1177/1362361307086663. PMID 18308767.

- ↑ Szatmari P, Jones MB (2007). "Genetic epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders". In Volkmar FR. Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders (2nd ed ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 157–78. ISBN 0521549574.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Folstein SE, Rosen-Sheidley B (2001). "Genetics of autism: complex aetiology for a heterogeneous disorder". Nat Rev Genet. 2 (12): 943–55. doi:10.1038/35103559. PMID 11733747.

- ↑ Bolton P, Macdonald H, Pickles A; et al. (1994). "A case-control family history study of autism". J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 35 (5): 877–900. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb02300.x. PMID 7962246.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Sykes NH, Lamb JA (2007). "Autism: the quest for the genes". Expert Rev Mol Med. 9 (24): 1–15. doi:10.1017/S1462399407000452. PMID 17764594.

- ↑ Daniels JL, Forssen U, Hultman CM; et al. (2008). "Parental psychiatric disorders associated with autism spectrum disorders in the offspring". Pediatrics. 121 (5): e1357–62. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2296. PMID 18450879. Lay summary – UNC News (2008-05-05).

- ↑ Manzi B, Loizzo AL, Giana G, Curatolo P (2007). "Autism and metabolic diseases". J Child Neurol. doi:10.1177/0883073807308698. PMID 18079313.

- ↑ Matson JL, Nebel-Schwalm MS (2007). "Comorbid psychopathology with autism spectrum disorder in children: an overview". Res Dev Disabil. 28 (4): 341–52. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2005.12.004. PMID 16765022.

KSF

KSF