Biofilm

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 8 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 8 min

|

WikiDoc Resources for Biofilm |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Biofilm |

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Biofilm at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Biofilm at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Biofilm

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Biofilm Risk calculators and risk factors for Biofilm

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Biofilm |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Overview[edit | edit source]

A biofilm is a complex aggregation of microorganisms marked by the excretion of a protective and adhesive matrix. Biofilms are also often characterized by surface attachment, structural heterogeneity, genetic diversity, complex community interactions, and an extracellular matrix of polymeric substances.

Single-celled organisms generally exhibit two distinct modes of behavior. The first is the familiar free floating, or planktonic, form in which single cells float or swim independently in some liquid medium. The second is an attached state in which cells are closely packed and firmly attached to each other and usually form a solid surface. A change in behavior is triggered by many factors, including quorum sensing, as well as other mechanisms that vary between species. When a cell switches modes, it undergoes a phenotypic shift in behavior in which large suites of genes are up- and down- regulated.

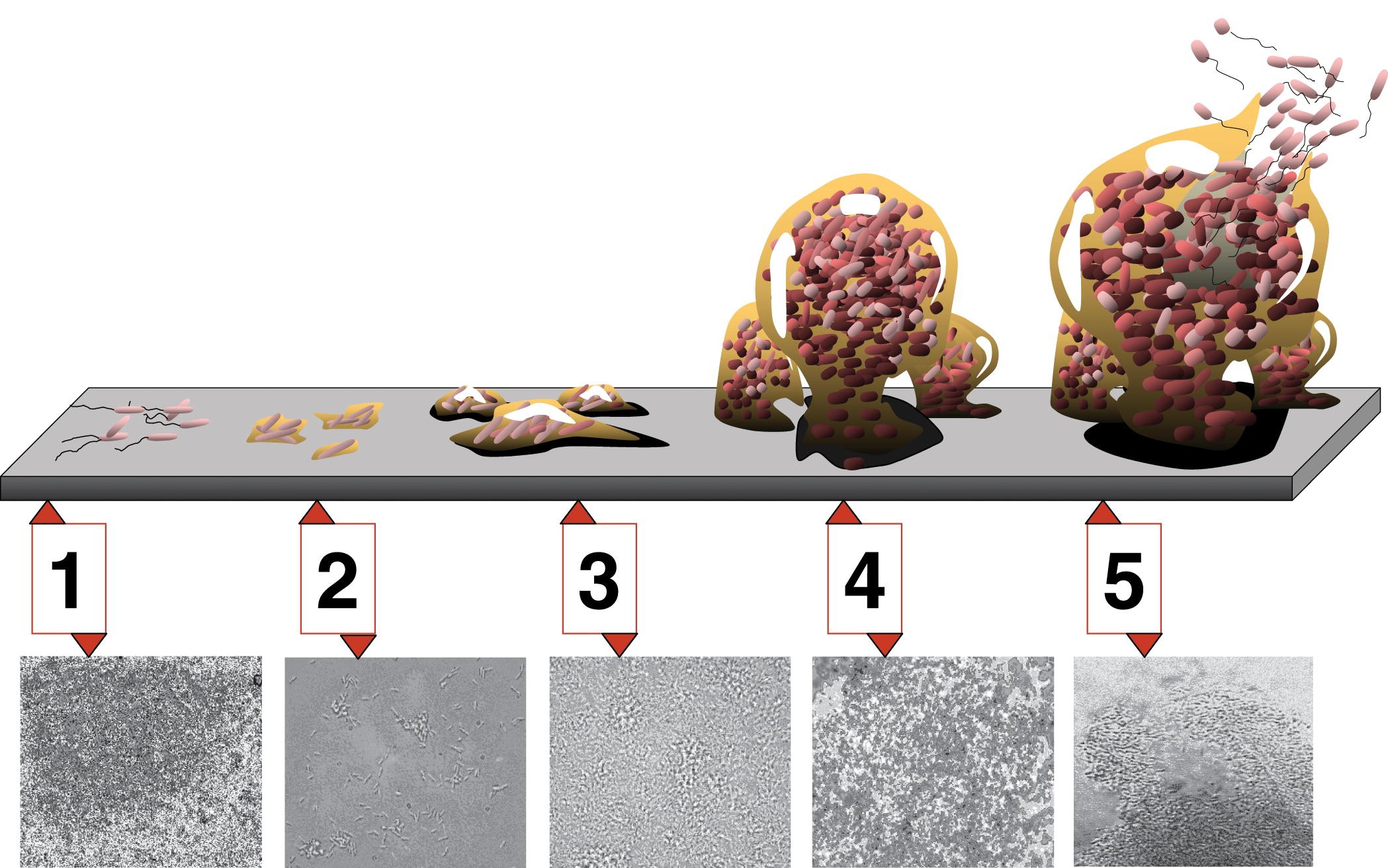

Formation[edit | edit source]

Formation of a biofilm begins with the attachment of free-floating microorganisms to a surface. These first colonists adhere to the surface initially through weak, reversible van der Waals forces. If the colonists are not immediately separated from the surface, they can anchor themselves more permanently using cell adhesion molecules such as pili.[1]

The first colonists facilitate the arrival of other cells by providing more diverse adhesion sites and beginning to build the matrix that holds the biofilm together. Some species are not able to attach to a surface on their own but are often able to anchor themselves to the matrix or directly to earlier colonists. It is during this colonization that the cells are able to communicate via quorum sensing. Once colonization has begun, the biofilm grows through a combination of cell division and recruitment. The final stage of biofilm formation is known as development, and is the stage in which the biofilm is established and may only change in shape and size. This development of biofilm allows for the cells to become more antibiotic resistant.

Properties[edit | edit source]

Biofilms are usually found on solid substrates submerged in or exposed to some aqueous solution, although they can form as floating mats on liquid surfaces and also on the surface of leaves, particularly in high humidity climates. Given sufficient resources for growth, a biofilm will quickly grow to be macroscopic. Biofilms can contain many different types of microorganism, e.g. bacteria, archaea, protozoa, fungi and algae; each group performing specialized metabolic functions. However, some organisms will form monospecies films under certain conditions.

Extracellular matrix[edit | edit source]

The biofilm is held together and protected by a matrix of excreted polymeric compounds called EPS. EPS is an abbreviation for either extracellular polymeric substance or exopolysaccharide. This matrix protects the cells within it and facilitates communication among them through biochemical signals. Some biofilms have been found to contain water channels that help distribute nutrients and signalling molecules. This matrix is strong enough that under certain conditions, biofilms can become fossilized.

Bacteria living in a biofilm usually have significantly different properties from free-floating bacteria of the same species, as the dense and protected environment of the film allows them to cooperate and interact in various ways. One benefit of this environment is increased resistance to detergents and antibiotics, as the dense extracellular matrix and the outer layer of cells protect the interior of the community. In some cases antibiotic resistance can be increased 1000 fold.[2]

Examples[edit | edit source]

Biofilms are ubiquitous. Nearly every species of microorganism, not only bacteria and archaea, have mechanisms by which they can adhere to surfaces and to each other.

- Biofilms can be found on rocks and pebbles at the bottom of most streams or rivers and often form on the surface of stagnant pools of water. In fact, biofilms are important components of foodchains in rivers and streams and are grazed by the aquatic invertebrates upon which many fish feed.

- Biofilms grow in hot, acidic pools in Yellowstone National Park (USA) and on glaciers in Antarctica.

- In industrial environments, biofilms can develop on the interiors of pipes, which can lead to clogging and corrosion. Biofilms on floors and counters can make sanitation difficult in food preparation areas. Biofilms in cooling water systems are known to reduce heat transfer[3] and harbour Legionella bacteria[4].

- Biofilms can also be harnessed for constructive purposes. For example, many sewage treatment plants include a treatment stage in which waste water passes over biofilms grown on filters, which extract and digest organic compounds. In such biofilms, bacteria are mainly responsible for removal of organic matter (BOD); whilst protozoa and rotifers are mainly responsible for removal of suspended solids (SS), including pathogens and other microorganisms. Slow sand filters rely on biofilm development in the same way to filter surface water from lake, spring or river sources for drinking purposes.

- Biofilms can help eliminate petroleum oil from contaminated oceans or marine systems. The oil is eliminated by the hydrocarbon-degrading activities of microbial communities, in particular by a remarkable recently discovered group of specialists, the so-called hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria (HCB).[5]

- Biofilms are also present on the teeth of most animals as dental plaque, where they may become responsible for tooth decay and gum disease.

Biofilms and infectious diseases[edit | edit source]

Biofilms have been found to be involved in a wide variety of microbial infections in the body, by one estimate 80% of all infections.[6] Infectious processes in which biofilms have been implicated include common problems such as urinary tract infections, catheter infections, middle-ear infections, formation of dental plaque[7], gingivitis[7], coating contact lenses[8], and less common but more lethal processes such as endocarditis, infections in cystic fibrosis, and infections of permanent indwelling devices such as joint prostheses and heart valves.[9][10]

It has recently been shown that biofilms are present on the removed tissue of 80% of patients undergoing surgery for chronic sinusitis. The patients with biofilms were shown to have been denuded of cilia and goblet cells, unlike the controls without biofilms who had normal cilia and goblet cell morphology.[11] Biofilms were also found on samples from two of 10 healthy controls mentioned. The species of bacteria from interoperative cultures did not correspond to the bacteria species in the biofilm on the respective patient's tissue. In other words, the cultures were negative though the bacteria were present.[12]

New staining techniques are being developed to differentiate bacterial cells growing in living animals, e.g. from tissues with allergy-inflammations .[13]

Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms[edit | edit source]

The achievements of medical care in industrialised societies are markedly impaired due to chronic opportunistic infections that have become increasingly apparent in immunocompromised patients and the aging population. Chronic infections remain a major challenge for the medical profession and are of great economic relevance because traditional antibiotic therapy is usually not sufficient to eradicate these infections. One major reason for persistence seems to be the capability of the bacteria to grow within biofilms that protects them from adverse environmental factors. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is not only an important opportunistic pathogen and causative agent of emerging nosocomial infections but can also be considered a model organism for the study of diverse bacterial mechanisms that contribute to bacterial persistence. In this context the elucidation of the molecular mechanisms responsible for the switch from planctonic growth to a biofilm phenotype and the role of inter-bacterial communication in persistent disease should provide new insights in P. aeruginosa pathogenicity, contribute to a better clinical management of chronically infected patients and should lead to the identification of new drug targets for the development of alternative anti-infective treatment strategies.[14]

Dental plaque[edit | edit source]

Dental plaque is the material that adheres to the teeth and consists of bacterial cells (mainly Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguis), salivary polymers and bacterial extracellular products. Plaque is a biofilm on the surfaces of the teeth. This accumulation of microorganisms subject the teeth and gingival tissues to high concentrations of bacterial metabolites which results in dental disease.[7]

See also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- Allison, D. (2000). Community Structure and Co-Operation in Biofilms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521793025.

- Lappin-Scott, Hilary (2003). Microbial Biofilms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052154212X.

- "A Friendly Guide to Biofilm Basics & the CBE". Center for Biofilm Engineering, Montana State University.

Footnotes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ JPG Images: niaid.nih.gov erc.montana.edu

- ↑ Stewart P, Costerton J (2001). "Antibiotic resistance of bacteria in biofilms". Lancet. 358 (9276): 135–8. PMID 11463434.

- ↑ W.G. Characklis, M.J. Nimmons and B.F. Picologlou, Influence of fouling biofilms on Heat transfer, Heat Trans. Eng. 3 (1981), pp. 23–37

- ↑ Murga et al, Microbiology (2001), 147; "Role of biofilms in the survival of Legionella pneumophila in a model potable-water system" pp3121–3126

- ↑ Martins VAP; et al. (2008). "Genomic Insights into Oil Biodegradation in Marine Systems". Microbial Biodegradation: Genomics and Molecular Biology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-17-2.

- ↑ "Research on microbial biofilms (PA-03-047)". NIH, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. December 20, 2002.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Rogers A H (editor). (2008). Molecular Oral Microbiology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-24-0 .

- ↑ Imamura Y, Chandra J, Mukherjee PK, Lattif AA, Szczotka-Flynn LB, Pearlman E, Lass JH, O'Donnell K, Ghannoum MA (2008). "Fusarium and Candida albicans Biofilms on Soft Contact Lenses: Model Development, Influence of Lens Type, and Susceptibility to Lens Care Solutions". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52 (1): 171–182. PMID 17999966.

- ↑ Lewis K (2001). "Riddle of biofilm resistance". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45 (4): 999–1007. PMID 11257008.

- ↑ Parsek M, Singh P (2003). "Bacterial biofilms: an emerging link to disease pathogenesis". Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57: 677–701. PMID 14527295.

- ↑ Sanclement J, Webster P, Thomas J, Ramadan H (2005). "Bacterial biofilms in surgical specimens of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis". Laryngoscope. 115 (4): 578–82. PMID 15805862.

- ↑ Sanderson A, Leid J, Hunsaker D (2006). "Bacterial biofilms on the sinus mucosa of human subjects with chronic rhinosinusitis". Laryngoscope. 116 (7): 1121–6. PMID 16826045.

- ↑ Leevy WM, Gammon ST, Jiang H, Johnson JR, Maxwell DJ, Jackson EN, Marquez M, Piwnica-Worms D, Smith BD (2006). "Optical imaging of bacterial infection in living mice using a fluorescent near-infrared molecular probe". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (51): 16476–7. PMID 17177377.

- ↑ Cornelis P (editor). (2008). Pseudomonas: Genomics and Molecular Biology (1st ed. ed.). Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-19-6 .

Further reading[edit | edit source]

- Ramadan H, Sanclement J, Thomas J (2005). "Chronic rhinosinusitis and biofilms". Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery. 132 (3): 414–7. PMID 15746854.

- Bendouah Z, Barbeau J, Hamad W, Desrosiers M (2006). "Biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa is associated with an unfavorable evolution after surgery for chronic sinusitis and nasal polyposis". Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery. 134 (6): 991–6. PMID 16730544.

KSF

KSF