Bone

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 11 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 11 min

|

WikiDoc Resources for Bone |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Bone at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Bone at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Bone

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Bone Risk calculators and risk factors for Bone

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

[edit | edit source]

Bones are rigid organs that form part of the endoskeleton of vertebrates. They function to move, support, and protect the various organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells and store minerals. Because bones come in a variety of shapes and have a complex internal and external structure, they are lightweight, yet strong and hard, in addition to fulfilling their many other functions. One of the types of tissues that makes up bone is the mineralized osseous tissue, also called bone tissue, that gives it rigidity and honeycomb-like three-dimensional internal structure. Other types of tissue found in bones include marrow, endosteum and periosteum, nerves, blood vessels and cartilage. There are 206 bones in the adult body, and about 300 bones in a infants body.

Functions

[edit | edit source]Bones have eight main functions:

- Protection — Bones can serve to protect internal organs, such as the skull protecting the brain or the ribs protecting the heart and lungs.

- Shape — Bones provide a frame to keep the body supported.

- Blood production — The marrow, located within the medullary cavity of long bones and the interstices of cancellous bone, produces blood cells in a process called haematopoiesis.

- Mineral storage — Bones act as reserves of minerals important for the body, most notably calcium and phosphorus.

- Movement — Bones, skeletal muscles, tendons, ligaments and joints function together to generate and transfer forces so that individual body parts or the whole body can be manipulated in three-dimensional space. The interaction between bone and muscle is studied in biomechanics.

- Acid-base balance — Bone buffers the blood against excessive pH changes by absorbing or releasing alkaline salts.

- Detoxification — Bone tissues can also store heavy metals and other foreign elements, removing them from the blood and reducing their effects on other tissues. These can later be gradually released for excretion.

- Sound transduction — Bones are important in the mechanical aspect of hearing.

Characteristics

[edit | edit source]The primary tissue of bone, osseous tissue, is a relatively hard and lightweight composite material, formed mostly of calcium phosphate in the chemical arrangement termed calcium hydroxylapatite (this is the osseous tissue that gives bones their rigidity). It has relatively high compressive strength but poor tensile strength, meaning it resists pushing forces well, but not pulling forces. While bone is essentially brittle, it does have a significant degree of elasticity contributed chiefly by collagen. All bones consist of living cells embedded in the mineralised organic matrix that makes up the osseous tissue.

Macrostructure

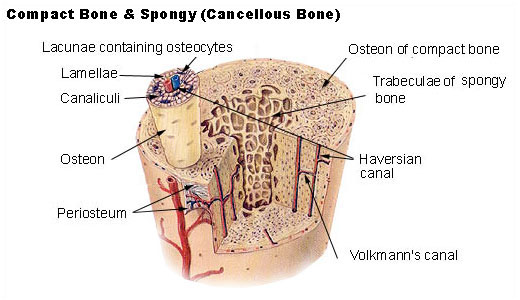

[edit | edit source]Bone is not a uniformly solid material, but rather has some spaces between its hard elements.

Compact bone

[edit | edit source]The hard outer layer of bones is composed of compact bone tissue, so-called due to its minimal gaps and spaces. This tissue gives bones their smooth, white, and solid appearance, and accounts for 80% of the total bone mass of an adult skeleton. Compact bone may also be referred to as dense bone or cortical bone.

Trabecular bone

[edit | edit source]Filling the interior of the organ is the trabecular bone tissue (an open cell porous network also called cancellous or spongy bone) which is comprised of a network of rod- and plate-like elements that make the overall organ lighter and allowing room for blood vessels and marrow. Trabecular bone accounts for the remaining 20% of total bone mass, but has nearly ten times the surface area of compact bone.

Cellular structure

[edit | edit source]There are several types of cells constituting the bone;

- Osteoblasts are mononucleate bone-forming cells which descend from osteoprogenitor cells. They are located on the surface of osteoid seams and make a protein mixture known as osteoid, which mineralizes to become bone. Osteoid is primarily composed of Type I collagen. Osteoblasts also manufacture hormones, such as prostaglandins, to act on the bone itself. They robustly produce alkaline phosphatase, an enzyme that has a role in the mineralisation of bone, as well as many matrix proteins. Osteoblasts are the immature bone cells.

- Bone lining cells are essentially inactive osteoblasts. They cover all of the available bone surface and function as a barrier for certain ions.

- Osteocytes originate from osteoblasts which have migrated into and become trapped and surrounded by bone matrix which they themselves produce. The spaces which they occupy are known as lacunae. Osteocytes have many processes which reach out to meet osteoblasts probably for the purposes of communication. Their functions include to varying degrees: formation of bone, matrix maintenance and calcium homeostasis. They possibly act as mechano-sensory receptors—regulating the bone's response to stress. They are mature bone cells.

- Osteoclasts are the cells responsible for bone resorption (remodeling of bone to reduce its volume). Osteoclasts are large, multinucleated cells located on bone surfaces in what are called Howship's lacunae or resorption pits. These lacunae, or resorption pits, are left behind after the breakdown of bone and often present as scalloped surfaces. Because the osteoclasts are derived from a monocyte stem-cell lineage, they are equipped with engulfment strategies similar to circulating macrophages. Osteoclasts mature and/or migrate to discrete bone surfaces. Upon arrival, active enzymes, such as tartrate resistant acid phosphatase, are secreted against the mineral substrate.

Molecular structure

[edit | edit source]Matrix

[edit | edit source]The matrix is the major constituent of bone, surrounding the cells. It has inorganic and organic parts.

Inorganic

[edit | edit source]The inorganic is mainly crystalline mineral salts and calcium, which is present in the form of hydroxyapatite. The matrix is initially laid down as unmineralized osteoid (manufactured by osteoblasts). Mineralisation involves osteoblasts secreting vesicles containing alkaline phosphatase. This cleaves the phosphate groups and acts as the foci for calcium and phosphate deposition. The vesicles then rupture and act as a centre for crystals to grow on.

Organic

[edit | edit source]The organic part of matrix is mainly Type I collagen. This is made intracellularly as tropocollagen and then exported. It then associates into fibrils. Also making up the organic part of matrix include various growth factors, the functions of which are not fully known. Other factors present include glycosaminoglycans, osteocalcin, osteonectin, bone sialo protein and Cell Attachment Factor. One of the main things that distinguishes the matrix of a bone from that of another cell is that the matrix in bone is hard.

Woven or lamellar

[edit | edit source]

Bone is first deposited as woven bone, in a disorganized structure with a high proportion of osteocytes in young and in healing injuries. Woven bone is weaker, with a small number of randomly oriented collagen fibers, but forms quickly. It is replaced by lamellar bone, which is highly organized in concentric sheets with a low proportion of osteocytes. Lamellar bone is stronger and filled with many collagen fibers parallel to other fibers in the same layer. The fibers run in opposite directions in alternating layers, much like plywood, assisting in the bone's ability to resist torsion forces. After a break, woven bone quickly forms and is gradually replaced by slow-growing lamellar bone on pre-existing calcified hyaline cartilage through a process known as "bony substitution."

Five types of bones

[edit | edit source]

There are five types of bones in the human body: long, short, flat, irregular and sesamoid.

- Long bones are longer than they are wide, consisting of a long shaft (the diaphysis) plus two articular (joint) surfaces, called epiphyses. They are comprised mostly of compact bone, but are generally thick enough to contain considerable spongy bone and marrow in the hollow centre (the medullary cavity). Most bones of the limbs (including the three bones of the fingers) are long bones, except for the kneecap (patella), and the carpal, metacarpal, tarsal and metatarsal bones of the wrist and ankle. The classification refers to shape rather than the size.

- Short bones are roughly cube-shaped, and have only a thin layer of compact bone surrounding a spongy interior. The bones of the wrist and ankle are short bones, as are the sesamoid bones.

- Flat bones are thin and generally curved, with two parallel layers of compact bones sandwiching a layer of spongy bone. Most of the bones of the skull are flat bones, as is the sternum.

- Irregular bones do not fit into the above categories. They consist of thin layers of compact bone surrounding a spongy interior. As implied by the name, their shapes are irregular and complicated. The bones of the spine and hips are irregular bones.

- Sesamoid bones are bones embedded in tendons. Since they act to hold the tendon further away from the joint, the angle of the tendon is increased and thus the force of the muscle is increased. Examples of sesamoid bones are the patella and the pisiform

Formation

[edit | edit source]The formation of bone during the fetal stage of development occurs by two methods: intramembranous and endochondral ossification.

Intramembranous ossification

[edit | edit source]Intramembranous ossification mainly occurs during formation of the flat bones of the skull; the bone is formed from mesenchyme tissue. The steps in intramembranous ossification are:

- Development of ossification center

- Calcification

- Formation of trabeculae

- Development of periosteum

Endochondral ossification

[edit | edit source]

Endochondral ossification, on the other hand, occurs in long bones, such as limbs; the bone is formed from cartilage. The steps in endochondral ossification are:

- Development of cartilage model

- Growth of cartilage model

- Development of the primary ossification center

- Development of medullary cavity

- Development of the secondary ossification center

- Formation of articular cartilage and epiphyseal plate

Endochondral ossification begins with points in the cartilage called "primary ossification centers." They mostly appear during fetal development, though a few short bones begin their primary ossification after birth. They are responsible for the formation of the diaphyses of long bones, short bones and certain parts of irregular bones. Secondary ossification occurs after birth, and forms the epiphyses of long bones and the extremities of irregular and flat bones. The diaphysis and both epiphyses of a long bone are separated by a growing zone of cartilage (the epiphyseal plate). When the child reaches skeletal maturity (18 to 25 years of age), all of the cartilage is replaced by bone, fusing the diaphysis and both epiphyses together (epiphyseal closure).

Bone marrow

[edit | edit source]There are two types of bone marrow, yellow and red, most commonly seen is red Bone marrow can be found in almost any bone that holds cancellous tissue. In newborns, all such bones are filled exclusively with red marrow (or hemopoietic marrow), but as the child ages it is mostly replaced by yellow, or fatty marrow. In adults, red marrow is mostly found in the flat bones of the skull, the ribs, the vertebrae and pelvic bones.

Remodeling

[edit | edit source]Remodeling or bone turnover is the process of resorption followed by replacement of bone with little change in shape and occurs throughout a person's life. Osteoblasts and osteoclasts, coupled together via paracrine cell signalling, are referred to as bone remodeling units.

Purpose

[edit | edit source]The purpose of remodeling is to regulate calcium homeostasis, repair micro-damaged bones (from everyday stress) but also to shape and sculpture the skeleton during growth.

Calcium balance

[edit | edit source]The process of bone resorption by the osteoclasts releases stored calcium into the systemic circulation and is an important process in regulating calcium balance. As bone formation actively fixes circulating calcium in its mineral form, removing it from the bloodstream, resorption actively unfixes it thereby increasing circulating calcium levels. These processes occur in tandem at site-specific locations.

Repair

[edit | edit source]Repeated stress, such as weight-bearing exercise or bone healing, results in the bone thickening at the points of maximum stress (Wolff's law). It has been hypothesized that this is a result of bone's piezoelectric properties, which cause bone to generate small electrical potentials under stress.

Medical conditions related to bones

[edit | edit source]Osteology

[edit | edit source]The study of bones and teeth is referred to as osteology. It is frequently used in anthropology, archeology and forensic science for a variety of tasks. This can include determining the nutritional, health, age or injury status of the individual the bones were taken from. Preparing fleshed bones for these types of studies can involve maceration - boiling fleshed bones to remove large particles, then hand-cleaning.

Typically anthropologists and archeologists study bone tools made by Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis. Bones can serve a number of uses such as projectile points or artistic pigments, and can be made from endoskeletal or external bones such as antler or tusk.

Alternatives to bony endoskeletons

[edit | edit source]There are several evolutionary alternatives to mammilary bone; though they have some similar functions, they are not completely functionally analogous to bone.

- Exoskeletons offer support, protection and levers for movement similar to endoskeletal bone. Different types of exoskeletons include shells, carapaces (consisting of calcium compounds or silica) and chitinous exoskeletons.

- A true endoskeleton (that is, protective tissue derived from mesoderm) is also present in Echinoderms. Porifera (sponges) possess simple endoskeletons that consist of calcareous or siliceous spicules and a spongin fiber network.

Exposed bone

[edit | edit source]Bone penetrating the skin and being exposed to the outside can be both a natural process in some animals, and due to injury:

- A deer's antlers are composed of bone

- The extinct predatory fish Dunkleosteus, instead of teeth, had sharp edges of hard exposed bone along its jaws

- A compound fracture occurs when the edges of a broken bone punctures the skin

- Though not strictly speaking exposed, a bird's beak is primarily bone covered in a layer of keratin

Terminology

[edit | edit source]Several terms are used to refer to features and components of bones throughout the body:

| Bone feature | Definition |

|---|---|

| articular process | A projection that contacts an adjacent bone. |

| articulation | The region where adjacent bones contact each other—a joint. |

| canal | A long, tunnel-like foramen, usually a passage for notable nerves or blood vessels. |

| condyle | A large, rounded articular process. |

| crest | A prominent ridge. |

| eminence | A relatively small projection or bump. |

| epicondyle | A projection near to a condyle but not part of the joint. |

| facet | A small, flattened articular surface. |

| foramen | An opening through a bone. |

| fossa | A broad, shallow depressed area. |

| fovea | A small pit on the head of a bone. |

| labyrinth | A cavity within a bone. |

| line | A long, thin projection, often with a rough surface. Also known as a ridge. |

| malleolus | One of two specific protuberances of bones in the ankle. |

| meatus | A short canal. |

| process | A relatively large projection or prominent bump.(gen.) |

| ramus | An arm-like branch off the body of a bone. |

| sinus | A cavity within a cranial bone. |

| spine | A relatively long, thin projection or bump. |

| suture | Articulation between cranial bones. |

| trochanter | One of two specific tuberosities located on the femur. |

| tubercle | A projection or bump with a roughened surface, generally smaller than a tuberosity. |

| tuberosity | A projection or bump with a roughened surface. |

Several terms are used to refer to specific features of long bones:

| Bone feature | Definition |

|---|---|

| diaphysis | The long, relatively straight main body of a long bone; region of primary ossification. Also known as the shaft. |

| epiphysis | The end regions of a long bone; regions of secondary ossification. |

| epiphyseal plate | Also known as the growth plate or physis. In a long bone it is a thin disc of hyaline cartilage that is positioned transversely between the epiphysis and metaphysis. In the long bones of humans, the epiphyseal plate disappears by twenty years of age. |

| head | The proximal articular end of the bone. |

| metaphysis | The region of a long bone lying between the epiphysis and diaphysis. |

| neck | The region of bone between the head and the shaft. |

References

[edit | edit source]- Marieb, E.N. (1998). Human Anatomy & Physiology, 4th ed. Menlo Park, California: Benjamin/Cummings Science Publishing.

- Netter, Frank H. (1987), Musculoskeletal system: anatomy, physiology, and metabolic disorders, Summit, New Jersey: Ciba-Geigy Corporation.

- Tortora, G. J. (1989), Principles of Human Anatomy, 5th ed. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers.

See also

[edit | edit source]External links

[edit | edit source]- Review (including references) of piezoelectricity and bone remodelling

- A good basic overview of bone biology from the Science Creative Quarterly

- Bone Health at Got Bones?

- Osteopathic physicians

Template:Bone and cartilage Template:Facial bones Template:Cranium Template:Sutures Template:Bones of upper extremity Template:Spine Template:Bones of lower extremity Template:Pelvis

af:Been

ar:عظم

ay:Ch'aka

bs:Kosti

br:Askorn

bg:Кост

ca:Os

cs:Kost

cy:Asgwrn

da:Knogle (anatomi)

de:Knochen

el:Οστό

eo:Osto

eu:Hezur

gd:Cnàmh

gl:Óso

ko:뼈

hr:Kosti

io:Osto

id:Tulang

is:Bein

it:Osso

he:עצם

la:Os (ossis - anatomia)

lv:Kauli

lt:Kaulas

ln:Mokúwa

hu:Csont

mk:Коска

nl:Bot (anatomie)

qu:Tullu

simple:Bone

sk:Kosť

sl:Kost

sr:Кост

sh:Kosti

su:Tulang

fi:Luu

sv:Ben (skelett)

tl:Buto (anatomiya)

ta:எலும்பு

th:กระดูก

uk:Кістка

KSF

KSF