Breast cancer laboratory tests

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 28 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 28 min

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Soroush Seifirad, M.D.[2], Ammu Susheela, and Mirdula Sharma

|

Breast Cancer Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Breast cancer laboratory tests On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Breast cancer laboratory tests |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Breast cancer laboratory tests |

Overview[edit | edit source]

Laboratory studies play a crucial role in prevention, diagnosis, staging, treatment planning, management, determining prognosis and follow up of patients with breast cancer. Among them are single gene studies (i. e. BRCA1, BRCA2, and HER2), multiple gene panels (i.e. Oncotype DX), tumor markers (Ki67), and metastatic markers such as serum alkaline phosphatase as a marker of bone metastasis. A variety of other blood chemistry tests are also used in the management process of patients with breast cancer, among them are liver function tests (alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST) , bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase) and markers of kidney function (BUN, creatinine).

HER2[edit | edit source]

- HER2 is a member of the human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER/EGFR/ERBB) family.

- Amplification or over-expression of this oncogene has been shown to play an important role in the development and progression of certain aggressive types of breast cancer.

- In recent years the protein has become an important biomarker and target of therapy for approximately 30% of breast cancer patients.[1] HER2 has several names among them are:

- Receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2

- CD340 (cluster of differentiation 340)

- proto-oncogene Neu

- Erbb2 (rodent), or ERBB2 (human)

- HER2 (from human epidermal growth factor receptor 2)

- HER2/neu [2][3][4]

Signaling pathways[edit | edit source]

- Signaling pathways activated by HER2 include:[5]

- mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)

- phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K/Akt)

- phospholipase C γ

- protein kinase C (PKC)

- Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)

- In a nutshell, signaling through the ErbB family of receptors promotes cell proliferation and opposes apoptosis, and therefore must be tightly regulated to prevent uncontrolled cell growth from occurring.

Cancer biopsy[edit | edit source]

- HER2 testing is performed in breast cancer patients to assess prognosis and to determine suitability for trastuzumab therapy.

- Trastuzumab has been associated with cardiac toxicity.[6]

- Tests are usually performed on biopsy samples obtained by either fine-needle aspiration, core needle biopsy, vacuum-assisted breast biopsy, or surgical excision.

- Immunohistochemistry is used to measure the amount of HER2 protein present in the sample.

- Examples of this assay include HercepTest, Dako, Glostrup, and Denmark. T

- he sample is given a score based on the cell membrane staining pattern. Specimens with equivocal IHC results should then be validated using fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH).

- FISH can be used to measure the number of copies of the gene which are present and is thought to be more reliable than IHC.[7]

Serum[edit | edit source]

- The extracellular domain of HER2 can be shed from the surface of tumour cells and enter the circulation.

- Measurement of serum HER2 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) offers a far less invasive method of determining HER2 status than a biopsy and consequently has been extensively investigated.

- Results so far have suggested that changes in serum HER2 concentrations may be useful in predicting response to trastuzumab therapy.[8]

- However, its ability to determine eligibility for trastuzumab therapy is less clear.[9]

Cancer[edit | edit source]

- Amplification, also known as the over-expression of the ERBB2 gene, occurs in approximately 15-30% of breast cancers.[1][10]

- It is strongly associated with increased disease recurrence and a poor prognosis.[11]

- HER2 is colocalised and most of the time, coamplified with the gene GRB7, which is a proto-oncogene associated with breast, testicular germ cell, gastric, and eosophageal tumours.

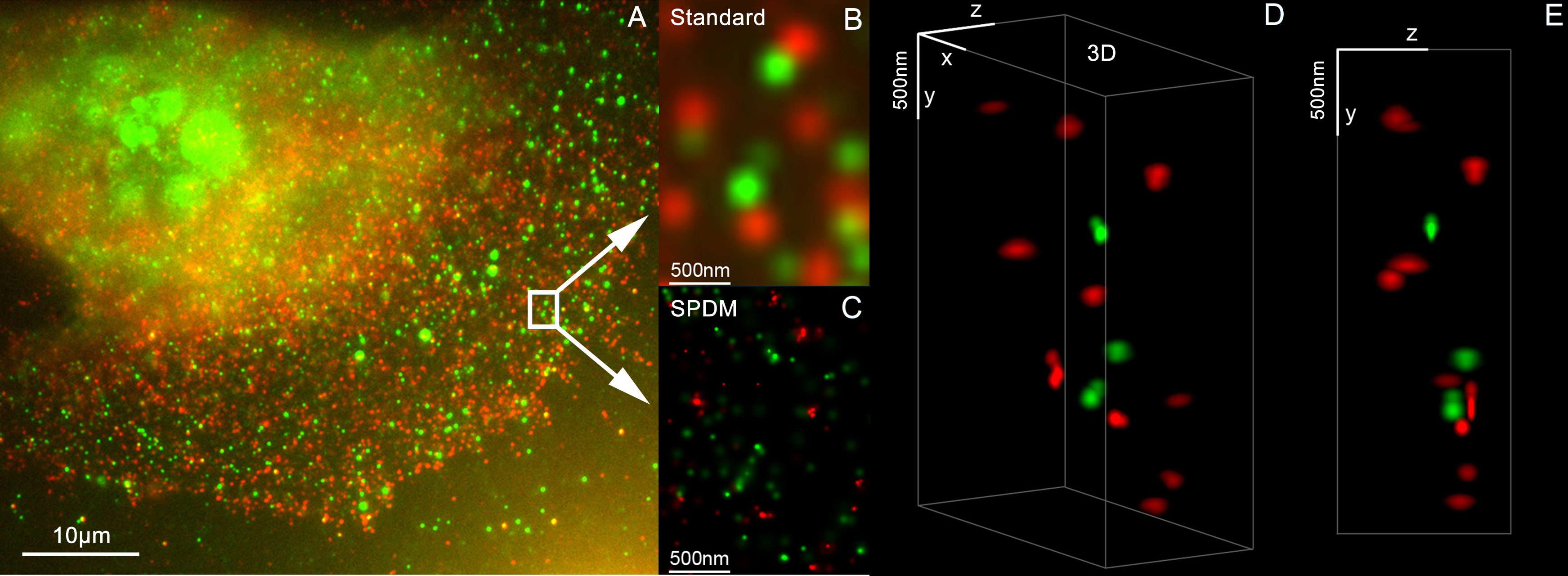

- HER2 proteins have been shown to form clusters in cell membranes that may play a role in tumorigenesis.[12][13]

- Recent evidence has implicated HER2 signaling in resistance to the EGFR-targeted cancer drug cetuximab.[14]

Mutations[edit | edit source]

- Furthermore, diverse structural alterations have been identified that cause ligand-independent firing of this receptor, doing so in the absence of receptor over-expression.

- HER2 is found in a variety of tumours and some of these tumors carry point mutations in the sequence specifying the transmembrane domain of HER2.

- Substitution of a valine for a glutamic acid in the transmembrane domain can result in the constitutive dimerization of this protein in the absence of a ligand.[15]

- HER2 mutations have been found in non-small-cell lung cancers (NSCLC) and can direct treatment.[16]

As a drug target[edit | edit source]

- HER2 is the target of the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab (marketed as Herceptin).

- Trastuzumab is effective only in cancers where HER2 is over-expressed.

- One year of trastuzumab therapy is recommended for all patients with HER2-positive breast cancer who are also receiving chemotherapy.[17] Twelve months of trastuzumab therapy is optimal. Randomized trials have demonstrated no additional benefit beyond 12 months, whereas 6 months has been shown to be inferior to 12.

- Trastuzumab is administered intravenously weekly or every 3 weeks.[18]

- An important downstream effect of trastuzumab binding to HER2 is an increase in p27, a protein that halts cell proliferation.[19]

- Another monoclonal antibody, Pertuzumab, which inhibits dimerisation of HER2 and HER3 receptors, was approved by the FDA for use in combination with trastuzumab in June 2012.

- As of November 2015, there are a number of ongoing and recently completed clinical trials of novel targeted agents for HER2+ metastatic breast cancer, e.g. margetuximab.[20]

- Additionally, NeuVax (Galena Biopharma) is a peptide-based immunotherapy that directs "killer" T cells to target and destroy cancer cells that express HER2. It has entered phase 3 clinical trials.

- It has been found that patients with ER+ (Estrogen receptor positive)/HER2+ compared with ER-/HER2+ breast cancers may actually benefit more from drugs that inhibit the PI3K/AKT molecular pathway.[21]

- Over-expression of HER2 can also be suppressed by the amplification of other genes. Research is currently being conducted to discover which genes may have this desired effect.

- The expression of HER2 is regulated by signaling through eostrogen receptors.

- Normally, estradiol and tamoxifen acting through the eostrogen receptor down-regulate the expression of HER2. However, when the ratio of the coactivator AIB-3 exceeds that of the corepressor PAX2, the expression of HER2 is upregulated in the presence of tamoxifen, leading to tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer.[22][23]

Multiple gene panels[edit | edit source]

- Oncotype DX®:

- For small hormone receptor-positive tumors that have not spread to more than 3 lymph nodes

- Also may be used for more advanced tumors

- Might be used for DCIS (ductal carcinoma in situ or stage 0 breast cancer). as well looks at a set of 21 genes in tumor biopsy samples to get a “recurrence score,” which is a number between 0 and 100.

- The score reflects the risk of breast cancer coming back (recurring) in the next 10 years and how likely you will benefit from getting chemo after surgery.

- The lower the score (usually 0-10) the lower the risk of recurrence.

- Benefit from chemotherapy is in doubt in most women with low scores

- An intermediate score (usually 11-25): intermediate risk of recurrence.

- Benefit from chemotherapy is in doubt in most women with intermediate-recurrence scores,

- Nevertheless chemotherapy is believed to be beneficial for women younger than 50 with a higher intermediate score (16-25)

- The possible risks and benefits of chemo should be weighted and discussed prior to decision making.

- A high score (usually 26-100): higher risk of recurrence.Chemotherapy is recommended for women with high scores in order to help lower the chance of cancer *recurrence.

- OncotypeDx is the only multigene panel with level I of evidence, and hence has been incorporated in the AJCC staging system

- MammaPrint®:

- To determine the likelihood of cancer recurrence in a distant part of the body after treatment.

- May be used in any type of breast cancer with stage 1 or 2 that has spread to no more than 3 lymph nodes.

- Hormone and HER2 status are also evaluated in this test. Seventy different genes are examined in this test to determine the 10 years cancer recurrence

- The test results are reported as either “low risk” or “high risk.”

- Unlike OncotypeDx has not been incorporated in the AJCC staging system yet.

BRCA1/BRCA2[edit | edit source]

BRCA1[edit | edit source]

- The human BRCA1 gene is located on the long (q) arm of chromosome 17 at region 2 band 1, from base pair 41,196,312 to base pair 41,277,500 (Build GRCh37/hg19) (map).[24]

- BRCA1 orthologs have been identified in most vertebrates for which complete genome data are available [25].

Function and mechanism[edit | edit source]

- BRCA1 is part of a complex that repairs double-strand breaks in DNA. Th

- In the nucleus of many types of normal cells, the BRCA1 protein interacts with RAD51 during repair of DNA double-strand breaks.[26]

- These breaks can be caused by natural radiation or other exposures, but also occur when chromosomes exchange genetic material (homologous recombination, e.g., "crossing over" during meiosis). TBy influencing DNA damage repair, these three proteins play a role in maintaining the stability of the human genome.

- BRCA1 is also involved in another type of DNA repair, termed mismatch repair.

- BRCA1 interacts with the DNA mismatch repair protein MSH2.[27]

- MSH2, MSH6, PARP and some other proteins involved in single-strand repair are reported to be elevated in BRCA1-deficient mammary tumors.[28]

- A protein called valosin-containing protein (VCP, also known as p97) plays a role to recruit BRCA1 to the damaged DNA sites.

- After ionizing radiation, VCP is recruited to DNA lesions and cooperates with the ubiquitin ligase RNF8 to orchestrate assembly of signaling complexes for efficient DSB repair.[29]

- BRCA1 interacts with VCP.[30]

- BRCA1 also interacts with c-Myc, and other proteins that are critical to maintain genome stability.[31]

- BRCA1 directly binds to DNA, with higher affinity for branched DNA structures. This ability to bind to DNA contributes to its ability to inhibit the nuclease activity of the MRN complex as well as the nuclease activity of Mre11 alone.[32]

- This may explain a role for BRCA1 to promote lower fidelity DNA repair by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ).[33]

- BRCA1 also colocalizes with γ-H2AX (histone H2AX phosphorylated on serine-139) in DNA double-strand break repair foci, indicating it may play a role in recruiting repair factors.[34][35]

- Formaldehyde and acetaldehyde are common environmental sources of DNA cross links that often require repairs mediated by BRCA1 containing pathways.[36][37]

- This DNA repair function is essential; mice with loss-of-function mutations in both BRCA1 alleles are not viable, and as of 2015 only two adults were known to have loss-of-function mutations in both alleles; both had congenital or developmental issues, and both had cancer. One was presumed to have survived to adulthood because one of the BRCA1 mutations was hypomorphic.[38]

- Certain variations of the BRCA1 gene lead to an increased risk for breast cancer as part of a hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndrome.

- Researchers have identified hundreds of mutations in the BRCA1 gene, many of which are associated with an increased risk of cancer.

- Females with an abnormal BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene have up to an 80% risk of developing breast cancer by age 90; increased risk of developing ovarian cancer is about 55% for females with BRCA1 mutations and about 25% for females with BRCA2 mutations.[39]

- These mutations can be changes in one or a small number of DNA base pairs (the building-blocks of DNA), and can be identified with PCR and DNA sequencing.

- In some cases, large segments of DNA are rearranged. Those large segments, also called large rearrangements, can be a deletion or a duplication of one or several exons in the gene.

- Classical methods for mutation detection (sequencing) are unable to reveal these types of mutation.[40]

- Other methods have been proposed: traditional quantitative PCR,[41] Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA),[42] and Quantitative Multiplex PCR of Short Fluorescent Fragments (QMPSF).[43]

- Newer methods have also been recently proposed: heteroduplex analysis (HDA) by multi-capillary electrophoresis or also dedicated oligonucleotides array based on comparative genomic hybridization (array-CGH).[44]

- Some results suggest that hypermethylation of the BRCA1 promoter, which has been reported in some cancers, could be considered as an inactivating mechanism for BRCA1 expression.[45]

- A mutated BRCA1 gene usually makes a protein that does not function properly

- . Researchers believe that the defective BRCA1 protein is unable to help fix DNA damage leading to mutations in other genes.

- These mutations can accumulate and may allow cells to grow and divide uncontrollably to form a tumor. Thus, BRCA1 inactivating mutations lead to a predisposition for cancer.

- BRCA1 mRNA 3' UTR can be bound by an miRNA, Mir-17 microRNA. It has been suggested that variations in this miRNA along with Mir-30 microRNA could confer susceptibility to breast cancer.[46]

- In addition to breast cancer, mutations in the BRCA1 gene also increase the risk of ovarian and prostate cancers. Moreover, precancerous lesions (dysplasia) within the Fallopian tube have been linked to BRCA1 gene mutations. Pathogenic mutations anywhere in a model pathway containing BRCA1 and BRCA2 greatly increase risks for a subset of leukemias and lymphomas.[47]

- Females who have inherited a defective BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene are at a greatly elevated risk to develop breast and ovarian cancer.

- Their risk of developing breast and/or ovarian cancer is so high, and so specific to those cancers, that many mutation carriers choose to have prophylactic surgery.

- There has been much conjecture to explain such apparently striking tissue specificity.

- Major determinants of where BRCA1/2 hereditary cancers occur are related to tissue specificity of the cancer pathogen, the agent that causes chronic inflammation or the carcinogen.

- The target tissue may have receptors for the pathogen, may become selectively exposed to an inflammatory process or to a carcinogen.

- An innate genomic deficit in a tumor suppressor gene impairs normal responses and exacerbates the susceptibility to disease in organ targets.

- This theory also fits data for several tumor suppressors beyond BRCA1 or BRCA2. A major advantage of this model is that it suggests there may be some options in addition to prophylactic surgery.[48]

Low expression of BRCA1 in breast and ovarian cancers[edit | edit source]

- BRCA1 expression is reduced or undetectable in the majority of high grade, ductal breast cancers.[49]

- It has long been noted that loss of BRCA1 activity, either by germ-line mutations or by down-regulation of gene expression, leads to tumor formation in specific target tissues.

- In particular, decreased BRCA1 expression contributes to both sporadic and inherited breast tumor progression.[50]

- Reduced expression of BRCA1 is tumorigenic because it plays an important role in the repair of DNA damages, especially double-strand breaks, by the potentially error-free pathway of homologous recombination.[51]

- Since cells that lack the BRCA1 protein tend to repair DNA damages by alternative more error-prone mechanisms, the reduction or silencing of this protein generates mutations and gross chromosomal rearrangements that can lead to progression to breast cancer.[51]

- Similarly, BRCA1 expression is low in the majority (55%) of sporadic epithelial ovarian cancers (EOCs) where EOCs are the most common type of ovarian cancer, representing approximately 90% of ovarian cancers.[52]

- In serous ovarian carcinomas, a sub-category constituting about 2/3 of EOCs, low BRCA1 expression occurs in more than 50% of cases.[53]

- Bowtell[54] reviewed the literature indicating that deficient homologous recombination repair caused by BRCA1 deficiency is tumorigenic.

- In particular this deficiency initiates a cascade of molecular events that sculpt the evolution of high-grade serous ovarian cancer and dictate its response to therapy.

- Especially noted was that BRCA1 deficiency could be the cause of tumorigenesis whether due to BRCA1 mutation or any other event that causes a deficiency of BRCA1 expression.

Mutation of BRCA1 in breast and ovarian cancer[edit | edit source]

- Only about 3%–8% of all women with breast cancer carry a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2.[55] Similarly, BRCA1 mutations are only seen in about 18% of ovarian cancers (13% germline mutations and 5% somatic mutations).[56]

- Thus, while BRCA1 expression is low in the majority of these cancers, BRCA1 mutation is not a major cause of reduced expression.

BRCA1 promoter hypermethylation in breast and ovarian cancer[edit | edit source]

- BRCA1 promoter hypermethylation was present in only 13% of unselected primary breast carcinomas.[57] Similarly, BRCA1 promoter hypermethylation was present in only 5% to 15% of EOC cases.[52]

- Thus, while BRCA1 expression is low in these cancers, BRCA1 promoter methylation is only a minor cause of reduced expression.

MicroRNA repression of BRCA1 in breast cancers[edit | edit source]

- There are a number of specific microRNAs, when overexpressed, that directly reduce expression of specific DNA repair proteins (see MicroRNA section DNA repair and cancer) In the case of breast cancer, microRNA-182 (miR-182) specifically targets BRCA1.[58]

- Almost all types of breast cancer were found to have an average of about 100-fold increase in miR-182, compared to normal breast tissue.[59]

- In breast cancer cell lines, there is an inverse correlation of BRCA1 protein levels with miR-182 expression.[58]

- Thus it appears that much of the reduction or absence of BRCA1 in high grade ductal breast cancers may be due to over-expressed miR-182.

- In addition to miR-182, a pair of almost identical microRNAs, miR-146a and miR-146b-5p, also repress BRCA1 expression.

- These two microRNAs are over-expressed in triple-negative tumors and their over-expression results in BRCA1 inactivation.[60]

- Thus, miR-146a and/or miR-146b-5p may also contribute to reduced expression of BRCA1 in these triple-negative breast cancers.

MicroRNA repression of BRCA1 in ovarian cancers[edit | edit source]

- In both serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (the precursor lesion to high grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HG-SOC)), and in HG-SOC itself, miR-182 is overexpressed in about 70% of cases.[61]

- In cells with over-expressed miR-182, BRCA1 remained low, even after exposure to ionizing radiation (which normally raises BRCA1 expression).[61]

- Thus much of the reduced or absent BRCA1 in HG-SOC may be due to over-expressed miR-182.

- Another microRNA known to reduce expression of BRCA1 in ovarian cancer cells is miR-9.[52] Among 58 tumors from patients with stage IIIC or stage IV serous ovarian cancers (HG-SOG), an inverse correlation was found between expressions of miR-9 and BRCA1,[52] so that increased miR-9 may also contribute to reduced expression of BRCA1 in these ovarian cancers.

| Population or subgroup | BRCA1 mutation(s)[62] | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| African-Americans | 943ins10, M1775R | [63] |

| Afrikaners | E881X | [64] |

| Ashkenazi Jewish | 185delAG, 188del11, 5382insC | [65][66] |

| Austrians | 2795delA, C61G, 5382insC, Q1806stop | [67] |

| Belgians | 2804delAA, IVS5+3A>G | [68][69] |

| Dutch | Exon 2 deletion, exon 13 deletion, 2804delAA | [68][70][71] |

| Finns | 3745delT, IVS11-2A>G | [72][73] |

| French | 3600del11, G1710X | [74] |

| French Canadians | C4446T | [75] |

| Germans | 5382insC, 4184del4 | [76][77] |

| Greeks | 5382insC | [78] |

| Hungarians | 300T>G, 5382insC, 185delAG | [79] |

| Italians | 5083del19 | [80] |

| Japanese | L63X, Q934X | [81] |

| Native North Americans | 1510insG, 1506A>G | [82] |

| Northern Irish | 2800delAA | [83] |

| Norwegians | 816delGT, 1135insA, 1675delA, 3347delAG | [84][85] |

| Pakistanis | 2080insA, 3889delAG, 4184del4, 4284delAG, IVS14-1A>G | [86] |

| Polish | 300T>G, 5382insC, C61G, 4153delA | [87][88] |

| Russians | 5382insC, 4153delA | [89] |

| Scottish | 2800delAA | [83][90] |

| Spanish | R71G | [91][92] |

| Swedish | Q563X, 3171ins5, 1201del11, 2594delC | [63][93] |

BRCA2[edit | edit source]

- BRCA2 and BRCA1 are normally expressed in the cells of breast and other tissue, where they help repair damaged DNA or destroy cells if DNA cannot be repaired.

- They are involved in the repair of chromosomal damage with an important role in the error-free repair of DNA double strand breaks.[94][95]

- If BRCA1 or BRCA2 itself is damaged by a BRCA mutation, damaged DNA is not repaired properly, and this increases the risk for breast cancer.[96][47]

- BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been described as "breast cancer susceptibility genes" and "breast cancer susceptibility proteins".

- The predominant allele has a normal tumor suppressive function whereas high penetrance mutations in these genes cause a loss of tumor suppressive function, which correlates with an increased risk of breast cancer.[97]

- The BRCA2 gene is located on the long (q) arm of chromosome 13 at position 12.3 (13q12.3).[98] The human reference BRCA 2 gene contains 27 exons, and the cDNA has 10,254 base pairs[99] coding for a protein of 3418 amino acids.[100][101]

- Certain variations of the BRCA2 gene increase risks for breast cancer as part of a hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndrome.

- Researchers have identified hundreds of mutations in the BRCA2 gene, many of which cause an increased risk of cancer. BRCA2 mutations are usually insertions or deletions of a small number of DNA base pairs in the gene.

- As a result of these mutations, the protein product of the BRCA2 gene is abnormal, and does not function properly. Researchers believe that the defective BRCA2 protein is unable to fix DNA damage that occurs throughout the genome.

- As a result, there is an increase in mutations due to error-prone translesion synthesis past un-repaired DNA damage, and some of these mutations can cause cells to divide in an uncontrolled way and form a tumor.

- In general, strongly inherited gene mutations (including mutations in BRCA2) account for only 5-10% of breast cancer cases; the specific risk of getting breast or other cancer for anyone carrying a BRCA2 mutation depends on many factors.[102]

- All germline BRCA2 mutations identified to date have been inherited, suggesting the possibility of a large "founder" effect in which a certain mutation is common to a well-defined population group and can theoretically be traced back to a common ancestor.

- Given the complexity of mutation screening for BRCA2, these common mutations may simplify the methods required for mutation screening in certain populations

- . Analysis of mutations that occur with high frequency also permits the study of their clinical expression.[103] A

- striking example of a founder mutation is found in Iceland, where a single BRCA2 (999del5) mutation accounts for virtually all breast/ovarian cancer families.[104][105]

- This frame-shift mutation leads to a highly truncated protein product. In a large study examining hundreds of cancer and control individuals, this 999del5 mutation was found in 0.6% of the general population

- . Of note, while 72% of patients who were found to be carriers had a moderate or strong family history of breast cancer, 28% had little or no family history of the disease.

- This strongly suggests the presence of modifying genes that affect the phenotypic expression of this mutation, or possibly the interaction of the BRCA2 mutation with environmental factors. Additional examples of founder mutations in BRCA2 are given in the table below.

| Population or subgroup | BRCA2 mutation(s)[103][62] | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Ashkenazi Jewish | 6174delT | [106] |

| Dutch | 5579insA | [71] |

| Finns | 8555T>G, 999del5, IVS23-2A>G | [72][73] |

| French Canadians | 8765delAG, 3398delAAAAG | [75][107][108] |

| Hungarians | 9326insA | [79] |

| Icelanders | 999del5 | [104][105] |

| Italians | 8765delAG | [109] |

| Northern Irish | 6503delTT | [83] |

| Pakistanis | 3337C>T | [86] |

| Scottish | 6503delTT | [83] |

| Slovenians | IVS16-2A>G | [110] |

| Spanish | 3034delAAAC(codon936), 9254del5 | [111] |

| Swedish | 4486delG | [63] |

Commercial BRCA mutation tests[edit | edit source]

- The sensitivity of commercial BRCA mutation tests like 23andMe is debated.

- For example, 23andMe’s testing formula is based on solely three genetic variants, most prevalent among Ashkenazi Jews, while most people carry other mutations of the gene.

- This will result in false negative results.

- 23andMe is a commercial BRCA1 screening test, with more than 10 million customers.

- Even if only a small percentage take the test, that’s thousands who could be misled.

- As accurately stated by Prof. Mary-Claire King, who discovered the BRCA1, “The F.D.A. should not have permitted this out-of-date approach to be used for medical purposes. Misleading, falsely reassuring results from their incomplete testing can cost women’s lives.”

Blood chemistry[edit | edit source]

Blood chemistry tests measure certain chemicals in the blood. They show how well certain organs are functioning and can also be used to detect abnormalities. They are used to stage breast cancer. [112]

- Urea (blood urea nitrogen or BUN) and creatinine may be measured to check kidney function. Kidney function is checked before chemotherapy is given and may be rechecked during or after treatment.

- Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST) and alkaline phosphatase may be measured to check liver function.

- Increased levels could indicate that cancer has spread to the liver.

- Alkaline phosphatase can also be used to check for cancer in the bone.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mitri Z, Constantine T, O'Regan R (2012). "The HER2 Receptor in Breast Cancer: Pathophysiology, Clinical Use, and New Advances in Therapy". Chemotherapy Research and Practice. 2012: 743193. doi:10.1155/2012/743193. PMC 3539433. PMID 23320171.

- ↑ "ERBB2 erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-06-14.

- ↑ Reference, Genetics Home. "ERBB2". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ↑ Barh D, Gunduz M (2015-01-22). Noninvasive Molecular Markers in Gynecologic Cancers. CRC Press. p. 427. ISBN 9781466569393.

- ↑ Roy V, Perez EA (November 2009). "Beyond trastuzumab: small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors in HER-2-positive breast cancer". The Oncologist. 14 (11): 1061–9. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0142. PMID 19887469.

- ↑ Telli ML, Hunt SA, Carlson RW, Guardino AE (August 2007). "Trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity: calling into question the concept of reversibility". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 25 (23): 3525–33. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0106. PMID 17687157.

- ↑ Giuliano AE, Hurvitz SA (2019). "Breast Disorder". In Papadakis MA, McPhee SJ, Rabow MW. Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Ali SM, Carney WP, Esteva FJ, Fornier M, Harris L, Köstler WJ, Lotz JP, Luftner D, Pichon MF, Lipton A (September 2008). "Serum HER-2/neu and relative resistance to trastuzumab-based therapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer". Cancer. 113 (6): 1294–301. doi:10.1002/cncr.23689. PMID 18661530.

- ↑ Lennon S, Barton C, Banken L, Gianni L, Marty M, Baselga J, Leyland-Jones B (April 2009). "Utility of serum HER2 extracellular domain assessment in clinical decision making: pooled analysis of four trials of trastuzumab in metastatic breast cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 27 (10): 1685–93. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8351. PMID 19255335.

- ↑ Burstein HJ (October 2005). "The distinctive nature of HER2-positive breast cancers". The New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (16): 1652–4. doi:10.1056/NEJMp058197. PMID 16236735.

- ↑ Tan M, Yu D (2007). "Molecular mechanisms of erbB2-mediated breast cancer chemoresistance". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 608: 119–29. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-74039-3_9. ISBN 978-0-387-74037-9. PMID 17993237.

- ↑ Nagy P, Jenei A, Kirsch AK, Szöllosi J, Damjanovich S, Jovin TM (June 1999). "Activation-dependent clustering of the erbB2 receptor tyrosine kinase detected by scanning near-field optical microscopy". Journal of Cell Science. 112 (11): 1733–41. PMID 10318765.

- ↑ Kaufmann R, Müller P, Hildenbrand G, Hausmann M, Cremer C (April 2011). "Analysis of Her2/neu membrane protein clusters in different types of breast cancer cells using localization microscopy". Journal of Microscopy. 242 (1): 46–54. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2818.2010.03436.x. PMID 21118230.

- ↑ Yonesaka K, Zejnullahu K, Okamoto I, Satoh T, Cappuzzo F, Souglakos J, et al. (September 2011). "Activation of ERBB2 signaling causes resistance to the EGFR-directed therapeutic antibody cetuximab". Science Translational Medicine. 3 (99): 99ra86. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3002442. PMC 3268675. PMID 21900593.

- ↑ Brandt-Rauf PW, Rackovsky S, Pincus MR (November 1990). "Correlation of the structure of the transmembrane domain of the neu oncogene-encoded p185 protein with its function". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (21): 8660–4. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.8660B. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.21.8660. PMC 55017. PMID 1978329.

- ↑ Mazières J, Peters S, Lepage B, Cortot AB, Barlesi F, Beau-Faller M, et al. (June 2013). "Lung cancer that harbors an HER2 mutation: epidemiologic characteristics and therapeutic perspectives". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 31 (16): 1997–2003. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.45.6095. PMID 23610105.

- ↑ Mates M, Fletcher GG, Freedman OC, Eisen A, Gandhi S, Trudeau ME, Dent SF (March 2015). "Systemic targeted therapy for her2-positive early female breast cancer: a systematic review of the evidence for the 2014 Cancer Care Ontario systemic therapy guideline". Current Oncology. 22 (Suppl 1): S114–22. doi:10.3747/co.22.2322. PMC 4381787. PMID 25848335.

- ↑ Jameson; et al. (2018). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 20th ed. McGraw-Hill Education. pp. Chapter 75: Breast Cancer. ISBN 978-1-259-64403-0.

- ↑ Le XF, Pruefer F, Bast RC (January 2005). "HER2-targeting antibodies modulate the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 via multiple signaling pathways". Cell Cycle. 4 (1): 87–95. doi:10.4161/cc.4.1.1360. PMID 15611642.

- ↑ Jiang H, Rugo HS (November 2015). "Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive (HER2+) metastatic breast cancer: how the latest results are improving therapeutic options". Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology. 7 (6): 321–39. doi:10.1177/1758834015599389. PMC 4622301. PMID 26557900.

- ↑ Loi S, Sotiriou C, Haibe-Kains B, Lallemand F, Conus NM, Piccart MJ, Speed TP, McArthur GA (2009). "Gene expression profiling identifies activated growth factor signaling in poor prognosis (Luminal-B) estrogen receptor positive breast cancer". BMC Medical Genomics. 2: 37. doi:10.1186/1755-8794-2-37. PMC 2706265. PMID 19552798. Lay summary – ScienceDaily.

- ↑ "Study sheds new light on tamoxifen resistance". Cordis News. Cordis. 2008-11-13. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- ↑ Hurtado A, Holmes KA, Geistlinger TR, Hutcheson IR, Nicholson RI, Brown M, Jiang J, Howat WJ, Ali S, Carroll JS (December 2008). "Regulation of ERBB2 by oestrogen receptor-PAX2 determines response to tamoxifen". Nature. 456 (7222): 663–6. Bibcode:2008Natur.456..663H. doi:10.1038/nature07483. PMC 2920208. PMID 19005469.

- ↑ National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine EntrezGene reference information for BRCA1 breast cancer 1, early onset (Homo sapiens)

- ↑ "BRCA1 gene tree". Ensembl.

- ↑ Boulton SJ (November 2006). "Cellular functions of the BRCA tumour-suppressor proteins". Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34 (Pt 5): 633–45. doi:10.1042/BST0340633. PMID 17052168.

- ↑ Wang Q, Zhang H, Guerrette S, Chen J, Mazurek A, Wilson T, Slupianek A, Skorski T, Fishel R, Greene MI (August 2001). "Adenosine nucleotide modulates the physical interaction between hMSH2 and BRCA1". Oncogene. 20 (34): 4640–9. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204625. PMID 11498787.

- ↑ Warmoes M, Jaspers JE, Pham TV, Piersma SR, Oudgenoeg G, Massink MP, Waisfisz Q, Rottenberg S, Boven E, Jonkers J, Jimenez CR (July 2012). "Proteomics of mouse BRCA1-deficient mammary tumors identifies DNA repair proteins with potential diagnostic and prognostic value in human breast cancer". Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 11 (7): M111.013334. doi:10.1074/mcp.M111.013334. PMC 3394939. PMID 22366898.

- ↑ Meerang M, Ritz D, Paliwal S, Garajova Z, Bosshard M, Mailand N, Janscak P, Hübscher U, Meyer H, Ramadan K (November 2011). "The ubiquitin-selective segregase VCP/p97 orchestrates the response to DNA double-strand breaks". Nat. Cell Biol. 13 (11): 1376–82. doi:10.1038/ncb2367. PMID 22020440.

- ↑ Zhang H, Wang Q, Kajino K, Greene MI (2000). "VCP, a weak ATPase involved in multiple cellular events, interacts physically with BRCA1 in the nucleus of living cells". DNA Cell Biol. 19 (5): 253–263. doi:10.1089/10445490050021168. PMID 10855792.

- ↑ Wang Q, Zhang H, Kajino K, Greene MI (October 1998). "BRCA1 binds c-Myc and inhibits its transcriptional and transforming activity in cells". Oncogene. 17 (15): 1939–48. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202403. PMID 9788437.

- ↑ Paull TT, Cortez D, Bowers B, Elledge SJ, Gellert M (2001). "Direct DNA binding by Brca1". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (11): 6086–6091. doi:10.1073/pnas.111125998. PMC 33426. PMID 11353843.

- ↑ Durant ST, Nickoloff JA (2005). "Good timing in the cell cycle for precise DNA repair by BRCA1". Cell Cycle. 4 (9): 1216–22. doi:10.4161/cc.4.9.2027. PMID 16103751.

- ↑ Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedStarita2003 - ↑ Ye Q, Hu YF, Zhong H, Nye AC, Belmont AS, Li R (2001). "BRCA1-induced large-scale chromatin unfolding and allele-specific effects of cancer-predisposing mutations". The Journal of Cell Biology. 155 (6): 911–922. doi:10.1083/jcb.200108049. PMC 2150890. PMID 11739404.

- ↑ Friedenson B (November 2011). "A common environmental carcinogen unduly affects carriers of cancer mutations: carriers of genetic mutations in a specific protective response are more susceptible to an environmental carcinogen". Med. Hypotheses. 77 (5): 791–7. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2011.07.039. PMID 21839586.

- ↑ Ridpath JR, Nakamura A, Tano K, Luke AM, Sonoda E, Arakawa H, Buerstedde JM, Gillespie DA, Sale JE, Yamazoe M, Bishop DK, Takata M, Takeda S, Watanabe M, Swenberg JA, Nakamura J (December 2007). "Cells deficient in the FANC/BRCA pathway are hypersensitive to plasma levels of formaldehyde". Cancer Res. 67 (23): 11117–22. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3028. PMID 18056434.

- ↑ Prakash R, Zhang Y, Feng W, Jasin M (April 2015). "Homologous recombination and human health: the roles of BRCA1, BRCA2, and associated proteins". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 7 (4): a016600. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a016600. PMC 4382744. PMID 25833843.

- ↑ "Genetics". Breastcancer.org. 2012-09-17.

- ↑ Mazoyer S (May 2005). "Genomic rearrangements in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes". Hum. Mutat. 25 (5): 415–22. doi:10.1002/humu.20169. PMID 15832305.

- ↑ Barrois M, Bièche I, Mazoyer S, Champème MH, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Lidereau R (February 2004). "Real-time PCR-based gene dosage assay for detecting BRCA1 rearrangements in breast-ovarian cancer families". Clin. Genet. 65 (2): 131–6. doi:10.1111/j.0009-9163.2004.00200.x. PMID 14984472.

- ↑ Hogervorst FB, Nederlof PM, Gille JJ, McElgunn CJ, Grippeling M, Pruntel R, Regnerus R, van Welsem T, van Spaendonk R, Menko FH, Kluijt I, Dommering C, Verhoef S, Schouten JP, van't Veer LJ, Pals G (April 2003). "Large genomic deletions and duplications in the BRCA1 gene identified by a novel quantitative method". Cancer Res. 63 (7): 1449–53. PMID 12670888.

- ↑ Casilli F, Di Rocco ZC, Gad S, Tournier I, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Frebourg T, Tosi M (September 2002). "Rapid detection of novel BRCA1 rearrangements in high-risk breast-ovarian cancer families using multiplex PCR of short fluorescent fragments". Hum. Mutat. 20 (3): 218–26. doi:10.1002/humu.10108. PMID 12203994.

- ↑ Rouleau E, Lefol C, Tozlu S, Andrieu C, Guy C, Copigny F, Nogues C, Bieche I, Lidereau R (September 2007). "High-resolution oligonucleotide array-CGH applied to the detection and characterization of large rearrangements in the hereditary breast cancer gene BRCA1". Clin. Genet. 72 (3): 199–207. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00849.x. PMID 17718857.

- ↑ Tapia T, Smalley SV, Kohen P, Muñoz A, Solis LM, Corvalan A, Faundez P, Devoto L, Camus M, Alvarez M, Carvallo P (2008). "Promoter hypermethylation of BRCA1 correlates with absence of expression in hereditary breast cancer tumors". Epigenetics. 3 (1): 157–63. doi:10.1186/bcr1858. PMID 18567944.

- ↑ Shen J, Ambrosone CB, Zhao H (March 2009). "Novel genetic variants in microRNA genes and familial breast cancer". Int. J. Cancer. 124 (5): 1178–82. doi:10.1002/ijc.24008. PMID 19048628.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Friedenson B (2007). "The BRCA1/2 pathway prevents hematologic cancers in addition to breast and ovarian cancers". BMC Cancer. 7: 152. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-7-152. PMC 1959234. PMID 17683622.

- ↑ Levin B, Lech D, Friedenson B (2012). "Evidence that BRCA1- or BRCA2-associated cancers are not inevitable". Mol Med. 18 (9): 1327–37. doi:10.2119/molmed.2012.00280. PMC 3521784. PMID 22972572.

- ↑ Wilson CA, Ramos L, Villaseñor MR, Anders KH, Press MF, Clarke K, Karlan B, Chen JJ, Scully R, Livingston D, Zuch RH, Kanter MH, Cohen S, Calzone FJ, Slamon DJ (1999). "Localization of human BRCA1 and its loss in high-grade, non-inherited breast carcinomas". Nat. Genet. 21 (2): 236–40. doi:10.1038/6029. PMID 9988281.

- ↑ Mueller CR, Roskelley CD (2003). "Regulation of BRCA1 expression and its relationship to sporadic breast cancer". Breast Cancer Res. 5 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1186/bcr557. PMC 154136. PMID 12559046.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Jacinto FV, Esteller M (2007). "Mutator pathways unleashed by epigenetic silencing in human cancer". Mutagenesis. 22 (4): 247–53. doi:10.1093/mutage/gem009. PMID 17412712.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 Sun C, Li N, Yang Z, Zhou B, He Y, Weng D, Fang Y, Wu P, Chen P, Yang X, Ma D, Zhou J, Chen G (2013). "miR-9 regulation of BRCA1 and ovarian cancer sensitivity to cisplatin and PARP inhibition". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 105 (22): 1750–8. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt302. PMID 24168967.

- ↑ McMillen BD, Aponte MM, Liu Z, Helenowski IB, Scholtens DM, Buttin BM, Wei JJ (2012). "Expression analysis of MIR182 and its associated target genes in advanced ovarian carcinoma". Mod. Pathol. 25 (12): 1644–53. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2012.118. PMID 22790015.

- ↑ Bowtell DD (2010). "The genesis and evolution of high-grade serous ovarian cancer". Nat. Rev. Cancer. 10 (11): 803–8. doi:10.1038/nrc2946. PMID 20944665.

- ↑ Brody LC, Biesecker BB (1998). "Breast cancer susceptibility genes. BRCA1 and BRCA2". Medicine (Baltimore). 77 (3): 208–26. doi:10.1097/00005792-199805000-00006. PMID 9653432.

- ↑ Pennington KP, Walsh T, Harrell MI, Lee MK, Pennil CC, Rendi MH, Thornton A, Norquist BM, Casadei S, Nord AS, Agnew KJ, Pritchard CC, Scroggins S, Garcia RL, King MC, Swisher EM (2014). "Germline and somatic mutations in homologous recombination genes predict platinum response and survival in ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinomas". Clin. Cancer Res. 20 (3): 764–75. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2287. PMC 3944197. PMID 24240112.

- ↑ Esteller M, Silva JM, Dominguez G, Bonilla F, Matias-Guiu X, Lerma E, Bussaglia E, Prat J, Harkes IC, Repasky EA, Gabrielson E, Schutte M, Baylin SB, Herman JG (2000). "Promoter hypermethylation and BRCA1 inactivation in sporadic breast and ovarian tumors". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92 (7): 564–9. doi:10.1093/jnci/92.7.564. PMID 10749912.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Moskwa P, Buffa FM, Pan Y, Panchakshari R, Gottipati P, Muschel RJ, Beech J, Kulshrestha R, Abdelmohsen K, Weinstock DM, Gorospe M, Harris AL, Helleday T, Chowdhury D (2011). "miR-182-mediated downregulation of BRCA1 impacts DNA repair and sensitivity to PARP inhibitors". Mol. Cell. 41 (2): 210–20. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.005. PMC 3249932. PMID 21195000.

- ↑ Krishnan K, Steptoe AL, Martin HC, Wani S, Nones K, Waddell N, Mariasegaram M, Simpson PT, Lakhani SR, Gabrielli B, Vlassov A, Cloonan N, Grimmond SM (2013). "MicroRNA-182-5p targets a network of genes involved in DNA repair". RNA. 19 (2): 230–42. doi:10.1261/rna.034926.112. PMC 3543090. PMID 23249749.

- ↑ Garcia AI, Buisson M, Bertrand P, Rimokh R, Rouleau E, Lopez BS, Lidereau R, Mikaélian I, Mazoyer S (2011). "Down-regulation of BRCA1 expression by miR-146a and miR-146b-5p in triple negative sporadic breast cancers". EMBO Mol Med. 3 (5): 279–90. doi:10.1002/emmm.201100136. PMC 3377076. PMID 21472990.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Liu Z, Liu J, Segura MF, Shao C, Lee P, Gong Y, Hernando E, Wei JJ (2012). "MiR-182 overexpression in tumourigenesis of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma". J. Pathol. 228 (2): 204–15. doi:10.1002/path.4000. PMID 22322863.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 den Dunnen JT, Antonarakis SE (2000). "Mutation nomenclature extensions and suggestions to describe complex mutations: a discussion". Human Mutation. 15 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<7::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-N. PMID 10612815.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Neuhausen SL (2000). "Founder populations and their uses for breast cancer genetics". Cancer Research. 2 (2): 77–81. doi:10.1186/bcr36. PMC 139426. PMID 11250694.

- ↑ Reeves MD, Yawitch TM, van der Merwe NC, van den Berg HJ, Dreyer G, van Rensburg EJ (July 2004). "BRCA1 mutations in South African breast and/or ovarian cancer families: evidence of a novel founder mutation in Afrikaner families". Int. J. Cancer. 110 (5): 677–82. doi:10.1002/ijc.20186. PMID 15146556.

- ↑ Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedStruewing1995 - ↑ Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedTonin1995 - ↑ Wagner TM, Möslinger RA, Muhr D, Langbauer G, Hirtenlehner K, Concin H, Doeller W, Haid A, Lang AH, Mayer P, Ropp E, Kubista E, Amirimani B, Helbich T, Becherer A, Scheiner O, Breiteneder H, Borg A, Devilee P, Oefner P, Zielinski C (1998). "BRCA1-related breast cancer in Austrian breast and ovarian cancer families: specific BRCA1 mutations and pathological characteristics". International Journal of Cancer. 77 (3): 354–360. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19980729)77:3<354::AID-IJC8>3.0.CO;2-N. PMID 9663595.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Peelen T, van Vliet M, Petrij-Bosch A, Mieremet R, Szabo C, van den Ouweland AM, Hogervorst F, Brohet R, Ligtenberg MJ, Teugels E, van der Luijt R, van der Hout AH, Gille JJ, Pals G, Jedema I, Olmer R, van Leeuwen I, Newman B, Plandsoen M, van der Est M, Brink G, Hageman S, Arts PJ, Bakker MM, Devilee P (1997). "A high proportion of novel mutations in BRCA1 with strong founder effects among Dutch and Belgian hereditary breast and ovarian cancer families". American Journal of Human Genetics. 60 (5): 1041–1049. PMC 1712432. PMID 9150151.

- ↑ Claes K, Machackova E, De Vos M, Poppe B, De Paepe A, Messiaen L (1999). "Mutation analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in the Belgian patient population and identification of a Belgian founder mutation BRCA1 IVS5 + 3A > G". Disease Markers. 15 (1–3): 69–73. doi:10.1155/1999/241046. PMC 3851655. PMID 10595255.

- ↑ Petrij-Bosch A, Peelen T, van Vliet M, van Eijk R, Olmer R, Drüsedau M, Hogervorst FB, Hageman S, Arts PJ, Ligtenberg MJ, Meijers-Heijboer H, Klijn JG, Vasen HF, Cornelisse CJ, van 't Veer LJ, Bakker E, van Ommen GJ, Devilee P (1997). "BRCA1 genomic deletions are major founder mutations in Dutch breast cancer patients". Nature Genetics. 17 (3): 341–345. doi:10.1038/ng1197-341. PMID 9354803.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Verhoog LC, van den Ouweland AM, Berns E, van Veghel-Plandsoen MM, van Staveren IL, Wagner A, Bartels CC, Tilanus-Linthorst MM, Devilee P, Seynaeve C, Halley DJ, Niermeijer MF, Klijn JG, Meijers-Heijboer H (2001). "Large regional differences in the frequency of distinct BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in 517 Dutch breast and/or ovarian cancer families". European Journal of Cancer. 37 (16): 2082–2090. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00244-1. PMID 11597388.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Huusko P, Pääkkönen K, Launonen V, Pöyhönen M, Blanco G, Kauppila A, Puistola U, Kiviniemi H, Kujala M, Leisti J, Winqvist R (1998). "Evidence of founder mutations in Finnish BRCA1 and BRCA2 families". American Journal of Human Genetics. 62 (6): 1544–1548. doi:10.1086/301880. PMC 1377159. PMID 9585608.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Pääkkönen K, Sauramo S, Sarantaus L, Vahteristo P, Hartikainen A, Vehmanen P, Ignatius J, Ollikainen V, Kääriäinen H, Vauramo E, Nevanlinna H, Krahe R, Holli K, Kere J (2001). "Involvement of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in breast cancer in a western Finnish sub-population". Genetic Epidemiology. 20 (2): 239–246. doi:10.1002/1098-2272(200102)20:2<239::AID-GEPI6>3.0.CO;2-Y. PMID 11180449.

- ↑ Muller D, Bonaiti-Pellié C, Abecassis J, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Fricker JP (2004). "BRCA1 testing in breast and/or ovarian cancer families from northeastern France identifies two common mutations with a founder effect". Familial Cancer. 3 (1): 15–20. doi:10.1023/B:FAME.0000026819.44213.df. PMID 15131401.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Tonin PN, Mes-Masson AM, Narod SA, Ghadirian P, Provencher D (1999). "Founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in French Canadian ovarian cancer cases unselected for family history". Clinical Genetics. 55 (5): 318–324. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.550504.x. PMID 10422801.

- ↑ Backe J, Hofferbert S, Skawran B, Dörk T, Stuhrmann M, Karstens JH, Untch M, Meindl A, Burgemeister R, Chang-Claude J, Weber BH (1999). "Frequency of BRCA1 mutation 5382insC in German breast cancer patients". Gynecologic Oncology. 72 (3): 402–406. doi:10.1006/gyno.1998.5270. PMID 10053113.

- ↑ "Mutation data of the BRCA1 gene". KMDB/MutationView (Keio Mutation Databases). Keio University.

- ↑ Ladopoulou A, Kroupis C, Konstantopoulou I, Ioannidou-Mouzaka L, Schofield AC, Pantazidis A, Armaou S, Tsiagas I, Lianidou E, Efstathiou E, Tsionou C, Panopoulos C, Mihalatos M, Nasioulas G, Skarlos D, Haites NE, Fountzilas G, Pandis N, Yannoukakos D (2002). "Germ line BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Greek breast/ovarian cancer families: 5382insC is the most frequent mutation observed". Cancer Letters. 185 (1): 61–70. doi:10.1016/S0304-3835(01)00845-X. PMID 12142080.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Van Der Looij M, Szabo C, Besznyak I, Liszka G, Csokay B, Pulay T, Toth J, Devilee P, King MC, Olah E (2000). "Prevalence of founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among breast and ovarian cancer patients in Hungary". International Journal of Cancer. 86 (5): 737–740. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000601)86:5<737::AID-IJC21>3.0.CO;2-1. PMID 10797299.

- ↑ Baudi F, Quaresima B, Grandinetti C, Cuda G, Faniello C, Tassone P, Barbieri V, Bisegna R, Ricevuto E, Conforti S, Viel A, Marchetti P, Ficorella C, Radice P, Costanzo F, Venuta S (2001). "Evidence of a founder mutation of BRCA1 in a highly homogeneous population from southern Italy with breast/ovarian cancer". Human Mutation. 18 (2): 163–164. doi:10.1002/humu.1167. PMID 11462242.

- ↑ Sekine M, Nagata H, Tsuji S, Hirai Y, Fujimoto S, Hatae M, Kobayashi I, Fujii T, Nagata I, Ushijima K, Obata K, Suzuki M, Yoshinaga M, Umesaki N, Satoh S, Enomoto T, Motoyama S, Tanaka K (2001). "Mutational analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 and clinicopathologic analysis of ovarian cancer in 82 ovarian cancer families: two common founder mutations of BRCA1 in Japanese population". Clinical Cancer Research. 7 (10): 3144–3150. PMID 11595708.

- ↑ Liede A, Jack E, Hegele RA, Narod SA (2002). "A BRCA1 mutation in Native North American families". Human Mutation. 19 (4): 460. doi:10.1002/humu.9027. PMID 11933205.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 83.3 The Scottish/Northern Irish BRCA1/BRCA2 Consortium (2003). "BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Scotland and Northern Ireland". British Journal of Cancer. 88 (8): 1256–1262. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600840. PMC 2747571. PMID 12698193.

- ↑ Borg A, Dørum A, Heimdal K, Maehle L, Hovig E, Møller P (1999). "BRCA1 1675delA and 1135insA account for one third of Norwegian familial breast-ovarian cancer and are associated with later disease onset than less frequent mutations". Disease Markers. 15 (1–3): 79–84. doi:10.1155/1999/278269. PMC 3851406. PMID 10595257.

- ↑ Heimdal K, Maehle L, Apold J, Pedersen JC, Møller P (2003). "The Norwegian founder mutations in BRCA1: high penetrance confirmed in an incident cancer series and differences observed in the risk of ovarian cancer". European Journal of Cancer. 39 (15): 2205–2213. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00548-3. PMID 14522380.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Liede A, Malik IA, Aziz Z, Rios Pd Pde L, Kwan E, Narod SA (2002). "Contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations to Breast and Ovarian Cancer in Pakistan". American Journal of Human Genetics. 71 (3): 595–606. doi:10.1086/342506. PMC 379195. PMID 12181777.

- ↑ Górski B, Byrski T, Huzarski T, Jakubowska A, Menkiszak J, Gronwald J, Pluzańska A, Bebenek M, Fischer-Maliszewska L, Grzybowska E, Narod SA, Lubiński J (2000). "Founder mutations in the BRCA1 gene in Polish families with breast-ovarian cancer". American Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (6): 1963–1968. doi:10.1086/302922. PMC 1378051. PMID 10788334.

- ↑ Perkowska M, BroZek I, Wysocka B, Haraldsson K, Sandberg T, Johansson U, Sellberg G, Borg A, Limon J (May 2003). "BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation analysis in breast-ovarian cancer families from northeastern Poland". Hum. Mutat. 21 (5): 553–4. doi:10.1002/humu.9139. PMID 12673801.

- ↑ Gayther SA, Harrington P, Russell P, Kharkevich G, Garkavtseva RF, Ponder BA (May 1997). "Frequently occurring germ-line mutations of the BRCA1 gene in ovarian cancer families from Russia". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 60 (5): 1239–42. PMC 1712436. PMID 9150173.

- ↑ Liede A, Cohen B, Black DM, Davidson RH, Renwick A, Hoodfar E, Olopade OI, Micek M, Anderson V, De Mey R, Fordyce A, Warner E, Dann JL, King MC, Weber B, Narod SA, Steel CM (February 2000). "Evidence of a founder BRCA1 mutation in Scotland". Br. J. Cancer. 82 (3): 705–11. doi:10.1054/bjoc.1999.0984. PMC 2363321. PMID 10682686.

- ↑ Vega A, Campos B, Bressac-De-Paillerets B, Bond PM, Janin N, Douglas FS, Domènech M, Baena M, Pericay C, Alonso C, Carracedo A, Baiget M, Diez O (June 2001). "The R71G BRCA1 is a founder Spanish mutation and leads to aberrant splicing of the transcript". Hum. Mutat. 17 (6): 520–1. doi:10.1002/humu.1136. PMID 11385711.

- ↑ Campos B, Díez O, Odefrey F, Domènech M, Moncoutier V, Martínez-Ferrandis JI, Osorio A, Balmaña J, Barroso A, Armengod ME, Benítez J, Alonso C, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Goldgar D, Baiget M (April 2003). "Haplotype analysis of the BRCA2 9254delATCAT recurrent mutation in breast/ovarian cancer families from Spain". Hum. Mutat. 21 (4): 452. doi:10.1002/humu.9133. PMID 12655574.

- ↑ Bergman A, Einbeigi Z, Olofsson U, Taib Z, Wallgren A, Karlsson P, Wahlström J, Martinsson T, Nordling M (October 2001). "The western Swedish BRCA1 founder mutation 3171ins5; a 3.7 cM conserved haplotype of today is a reminiscence of a 1500-year-old mutation". Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 9 (10): 787–93. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200704. PMID 11781691.

- ↑ Friedenson B (August 2007). "The BRCA1/2 pathway prevents hematologic cancers in addition to breast and ovarian cancers". BMC Cancer. 7: 152–162. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-7-152. PMC 1959234. PMID 17683622.

- ↑ Friedenson B (2008-06-08). "Breast cancer genes protect against some leukemias and lymphomas" (video). SciVee.

- ↑ "Breast and Ovarian Cancer Genetic Screening". Palo Alto Medical Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ↑ O'Donovan PJ, Livingston DM (April 2010). "BRCA1 and BRCA2: breast/ovarian cancer susceptibility gene products and participants in DNA double-strand break repair". Carcinogenesis. 31 (6): 961–7. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgq069. PMID 20400477.

- ↑ Wooster R, Neuhausen SL, Mangion J, Quirk Y, Ford D, Collins N, Nguyen K, Seal S, Tran T, Averill D (September 1994). "Localization of a breast cancer susceptibility gene, BRCA2, to chromosome 13q12-13". Science. 265 (5181): 2088–90. Bibcode:1994Sci...265.2088W. doi:10.1126/science.8091231. PMID 8091231.

- ↑ "BRCA2 breast cancer 2, early onset [Homo sapiens]". EntrezGene. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ↑ "Breast cancer type 2 susceptibility protein - Homo sapiens (Human)". P51587. UniProt.

- ↑ Williams-Jones B (2002). Genetic testing for sale: Implications of commercial brca testing in Canada (Ph.D.). The University of British Columbia.

- ↑ "High-Penetrance Breast and/or Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility Genes". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Lacroix M, Leclercq G (2005). "The "portrait" of hereditary breast cancer". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 89 (3): 297–304. doi:10.1007/s10549-004-2172-4. PMID 15754129.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 Thorlacius S, Olafsdottir G, Tryggvadottir L, Neuhausen S, Jonasson JG, Tavtigian SV, Tulinius H, Ogmundsdottir HM, Eyfjörd JE (1996). "A single BRCA2 mutation in male and female breast cancer families from Iceland with varied cancer phenotypes". Nature Genetics. 13 (1): 117–119. doi:10.1038/ng0596-117. PMID 8673089.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Thorlacius S, Sigurdsson S, Bjarnadottir H, Olafsdottir G, Jonasson JG, Tryggvadottir L, Tulinius H, Eyfjörd JE (1997). "Study of a single BRCA2 mutation with high carrier frequency in a small population". American Journal of Human Genetics. 60 (5): 1079–1085. PMC 1712443. PMID 9150155.

- ↑ Neuhausen S, Gilewski T, Norton L, Tran T, McGuire P, Swensen J, Hampel H, Borgen P, Brown K, Skolnick M, Shattuck-Eidens D, Jhanwar S, Goldgar D, Offit K (1996). "Recurrent BRCA2 6174delT mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish women affected by breast cancer". Nature Genetics. 13 (1): 126–128. doi:10.1038/ng0596-126. PMID 8673092.

- ↑ Oros KK, Leblanc G, Arcand SL, Shen Z, Perret C, Mes-Masson AM, Foulkes WD, Ghadirian P, Provencher D, Tonin PN (2006). "Haplotype analysis suggests common founders in carriers of recurrent BRCA2 mutation, 3398delAAAAG, in French Canadian hereditary breast and/ovarian cancer families". BMC Medical Genetics. 7 (23). doi:10.1186/1471-2350-7-23. PMC 1464093. PMID 16539696.

- ↑ Tonin PN (2006). "The limited spectrum of pathogenic BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in the French Canadian breast and breast-ovarian cancer families, a founder population of Quebec, Canada". Bull Cancer. 93 (9): 841–846. PMID 16980226.

- ↑ Pisano M, Cossu A, Persico I, Palmieri G, Angius A, Casu G, Palomba G, Sarobba MG, Rocca PC, Dedola MF, Olmeo N, Pasca A, Budroni M, Marras V, Pisano A, Farris A, Massarelli G, Pirastu M, Tanda F (2000). "Identification of a founder BRCA2 mutation in Sardinia". British Journal of Cancer. 82 (3): 553–559. doi:10.1054/bjoc.1999.0963. PMC 2363305. PMID 10682665.

- ↑ Krajc M, De Grève J, Goelen G, Teugels E (2002). "BRCA2 founder mutation in Slovenian breast cancer families". European Journal of Human Genetics. 10 (12): 879–882. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200886. PMID 12461697.

- ↑ Osorio A, Robledo M, Martínez B, Cebrián A, San Román JM, Albertos J, Lobo F, Benítez J (1998). "Molecular analysis of the BRCA2 gene in 16 breast/ovarian cancer Spanish families". Clin. Genet. 54: 142–7. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.1998.tb03717.x. PMID 9761393.

- ↑ Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedss

KSF

KSF