Congestive heart failure pathophysiology

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 11 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 11 min

| Title |

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ypYI_lmLD7g%7C350}} |

| Resident Survival Guide |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]; Saleh El Dassouki, M.D [3]; Atif Mohammad, MD

Overview

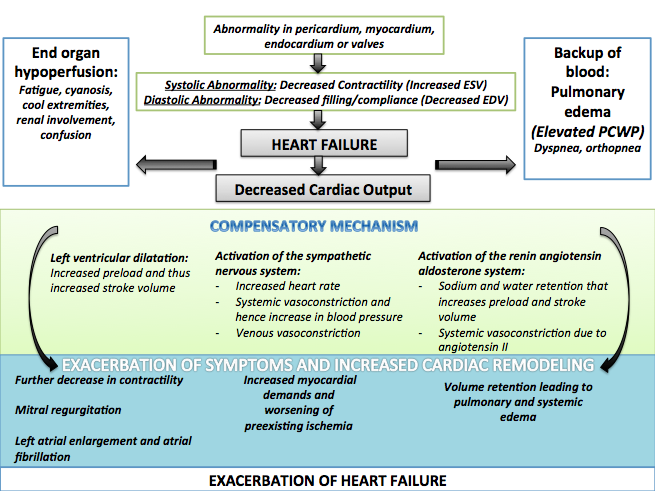

[edit | edit source]Heart failure is a complex syndrome whereby there is inadequate output of the heart to meet the metabolic demands of the body. Heart failure is caused by abnormal function of different anatomic parts of the heart including the pericardium, the myocardium, the endocardium, the heart valves and the great vessels. Heart failure is characterized by decreased cardiac output but not necessarily decreased ejection fraction. Symptoms of heart failure are due to a lack of both forward blood flow to the body, and backward flow into the lungs. The body tries to compensate for the low cardiac output by mechanisms that increase the preload and afterload. These mechanisms lead to exacerbation of the cardiac malfunction and symptoms associated with heart failure.

Pathophysiology

[edit | edit source]Decreased Cardiac Output

[edit | edit source]- Heart failure is defined as the inability of the heart to pump enough blood to meet the demands of the body.

- Therefore, heart failure is characterized by a reduced stroke volume as a result of a failure of systole, diastole or both:

- Systolic heart failure: Increased end systolic volume is usually caused by reduced contractility.

- Diastolic heart failure: Decreased end diastolic volume results from impaired ventricular filling, as occurs when the compliance of the ventricle falls (i.e. when the walls stiffen in diastolic dysfunction).

- Heart failure was once thought to be secondary to a depressed left ventricular ejection fraction. However, studies have shown that approximately 50% of patients who are diagnosed with heart failure have a normal ejection fraction (diastolic dysfunction). Patients may be broadly classified as having heart failure with depressed left ventricular ejection fraction (systolic dysfunction) or normal/preserved ejection fraction (diastolic dysfunction). Systolic and diastolic dysfunction commonly occur in conjunction with each other.

- Normally, blood flows from the lungs, into the pulmonary veins, into the left atrium, through the mitral valve, and finally into the left ventricle. When the left ventricle cannot be normally filled during diastole in both diastolic and systolic heart failure, blood will back up into the left atrium and, eventually, into the lungs. The result is a higher than normal pressure of blood within the vessels of the lung. As a result of hydrostatic forces, this high pressure leads to leaking of fluid (i.e. transudate) from the lung's vasculature into the air-spaces (alveoli) of the lungs. The result is pulmonary edema, a condition characterized by difficulty breathing, inadequate oxygenation of blood, and, if severe and untreated, death.

Underlying Cardiac Abnormalities Leading to Heart Failure

[edit | edit source]Heart failure may result from an abnormality or dysfunction of any one of the anatomical structures of the heart:

- Pericardium

- It can be damaged by infiltration of inflammatory cells (e.g. pericarditis) or fluid (pericardial effusion).

- Myocardium

- It can be damaged by ischemic injury (e.g. acute MI), toxins (e.g. chemotherapy), infiltration by inflammatory cells (e.g. myocarditis), pressure overload (e.g. hypertension or aortic stenosis), metabolic derangements, or volume overload (aortic insufficiency or mitral insufficiency).

- Endocardium

- It can be damaged by infiltration

- Valvular heart disease

- Valves can be damaged or dysfunctional from birth (bicuspid aortic valve) or can be acquired (e.g. endocarditis or rheumatic heart disease).

- Disorders of the great vessels

- Great vessels can be stiffened by atherosclerosis (e.g. hypertension) or can be chronically constricted (e.g. pulmonary hypertension)

Systolic versus Diastolic Dysfunction

[edit | edit source]Systolic Dysfunction

[edit | edit source]- Heart failure caused by systolic dysfunction is more readily recognized. It can be simplistically described as failure of the pump function of the heart.

- It is characterized by a decreased ejection fraction (less than 40%-45%). The strength of ventricular contraction is attenuated and inadequate for creating an adequate stroke volume, resulting in inadequate cardiac output. In general, this is caused by dysfunction or destruction of cardiac myocytes or their molecular components.

- In congenital diseases such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the molecular structure of individual myocytes is affected.

- Myocytes and their components can be damaged by inflammation (such as in myocarditis) or by infiltration (such as in amyloidosis).

- Toxins and pharmacological agents (such as ethanol, cocaine, and amphetamines) cause intracellular damage and oxidative stress.

- The most common mechanism of damage is ischemia causing infarction and scar formation.

- After myocardial infarction, dead myocytes are replaced by scar tissue, deleteriously affecting the function of the myocardium. On echocardiogram, this is manifest by abnormal or absent wall motion.

- Because the ventricle is inadequately emptied, ventricular end-diastolic pressure and volumes increase. This is transmitted to the atrium. On the left side of the heart, the increased pressure is transmitted to the pulmonary vasculature, and the resultant hydrostatic pressure favors extravasation of fluid into the lung parenchyma, causing pulmonary edema. On the right side of the heart, the increased pressure is transmitted to the systemic venous circulation and systemic capillary beds, favoring extravasation of fluid into the tissues of peripheral organs and extremities, resulting in dependent peripheral edema.

- Shown below is an image summarizing the pathophysiology of systolic heart failure.

Diastolic Dysfunction

[edit | edit source]- Heart failure caused by diastolic dysfunction is generally described as the failure of the ventricular chambers to adequately relax and results from stiffening of the ventricular walls. The consequence is reduced filling of chambers of the heart.

- The failure of ventricular relaxation also results in elevated end-diastolic pressures, and the end result is identical to the case of systolic dysfunction (pulmonary edema in left heart failure, peripheral edema in right heart failure.)

- Diastolic dysfunction can be caused by processes similar to those that cause systolic dysfunction, particularly causes that affect cardiac remodeling.

- Diastolic dysfunction typically becomes symptomatic in physiological conditions under which a high cardiac demand is required. Therefore, patients suffering from diastolic dysfunction are sensitive to increases in heart rate, and sudden bouts of tachycardia (which can be caused simply by physiological responses to exertion, fever, or dehydration, or by pathological tachyarrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response) which may result in flash pulmonary edema.

- Adequate rate control (usually with a pharmacological agent that slows down atrioventricular node conduction such as a calcium channel blocker or a beta-blocker) is therefore key to preventing decompensation.

- Left ventricular diastolic function can be determined through echocardiography by measurement of various parameters such as the E/A ratio (early-to-atrial left ventricular filling ratio), the E (early left ventricular filling) deceleration time, and the isovolumetric relaxation time.

Manifestations of Heart Failure

[edit | edit source]Pulmonary Edema

[edit | edit source]- The reduction in forward cardiac output leads to a rise in the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure. Rales usually develop if the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure is >25 mm Hg. Rales may not be present in the patient with chronic heart failure. Rales may develop at even lower pressures if left ventricular function deteriorates suddenly.

- Dyspnea and orthopnea occur due to interstitial edema within the lungs at lower pressures.

Hypotension

[edit | edit source]- Heart failure is characterized by decreased cardiac output and hence it causes low blood pressure.

Hypoperfusion

[edit | edit source]The reduction in forward cardiac output leads to hypoperfusion at rest which manifests as:

- Cool extremities

- Confusion and altered mentation

- Impaired renal perfusion and declining renal function (increased blood urea nitrogen [BUN] and serum creatinine [Cr] ; mostly leading to pre-renal failure [BUN:Cr > 20])

- Reduced perfusion of skeletal muscle causes atrophy of the muscle fibres. This can result in weakness, increased fatigue and decreased peak strength, all contributing to exercise intolerance and claudication.[1]

- In severe heart failure, the effects of decreased cardiac output and poor perfusion become more apparent, and patients will manifest symptoms of systemic hypoperfusion including generalized weakness, dizziness, and syncope.

Impaired Cardiac Reserve

[edit | edit source]As the heart works harder to meet normal metabolic demands, the amount cardiac output can increase in times of increased oxygen demand (e.g. exercise) is reduced. This contributes to the exercise intolerance commonly seen in heart failure. This translates to the loss of one's cardiac reserve. The cardiac reserve refers to the ability of the heart to work harder during exercise or strenuous activity. Since the heart has to work harder to meet the normal metabolic demands, it is incapable of meeting the metabolic demands of the body during exercise.

Compensatory Mechanisms and Their Associated Complications

[edit | edit source]- Shown below is an image summarizing the compensatory mechanisms of the heart along with their associated complications.

- Left ventricular systolic dysfunction is associated with a reduction in stroke volume, the amount of blood the heart ejects with each heart beat.

- The reduction in stroke volume leads to a reduction in cardiac output which is the stroke volume multiplied by the heart rate.

- There are several mechanisms to preserve forward cardiac output (the product of stroke volume and heart rate):

- Dilation of the left ventricle to increase the stroke volume and

- Increase in heart rate

Dilatation of the Left Ventricle:

[edit | edit source]- Dilation of the left ventricle increases volume and increases contractility up to a point (see Frank-Starling law of the heart). As further LV dilation occurs, however, contractility drops. This is due to reduced ability to cross-link actin and myosin filaments in over-stretched heart muscle.[2].

- As further dilation occurs, functional mitral regurgitation (MR) may develop despite an anatomically normal mitral valve.

- Left ventricular enlargement and lack of forward cardiac output can lead to left atrial enlargement. Left atrial dilation may lead to atrial fibrillation which occurs in 20% of patients with congestive heart failure. Atrial fibrillation diminishes left ventricular filling through the loss of the atrial kick (the atrial contraction) and due to an increase in the heart rate which reduces the time available for the left ventricle to fill.

Hypertrophy of the Myocardium:

[edit | edit source]- Hypertrophy (an increase in physical size) of the myocardium can develop, which is caused by the terminally differentiated heart muscle fibers increasing in size in an attempt to improve contractility. This may contribute to the increased stiffness and decreased ability to relax during diastole.

Activation of the Sympathetic Nervous System:

[edit | edit source]- Arterial blood pressure falls. This destimulates baroreceptors in the carotid sinus and aortic arch which link to the nucleus tractus solitarius. This center in the brain increases sympathetic activity, releasing catecholamines into the blood stream. Binding to alpha-1 receptors results in systemic arterial vasoconstriction. This helps restore blood pressure but also increases the total peripheral resistance, increasing the workload of the heart. Binding to beta-1 receptors in the myocardium increases the heart rate and make contractions more forceful, in an attempt to increase cardiac output. This also, however, increases the amount of work the heart has to perform.

- The increased heart rate, stimulated by increased sympathetic activity[3] maintains cardiac output. Initially, this helps compensate for heart failure by maintaining blood pressure and perfusion, but places further strain on the myocardium, increasing coronary perfusion requirements, which can lead to worsening of ischemic heart disease. Sympathetic activity may also cause potentially fatal arrhythmias.

- Increased sympathetic stimulation also causes the hypothalamus to secrete vasopressin (also known as antidiuretic hormone or ADH), which causes free water retention in the kidneys leading to hyponatremia. This free water retention increases total body blood volume and blood pressure.

Stimulation of the Renal / Adrenal / Sympathetic Axis:

[edit | edit source]- Reduced perfusion (blood flow) to the kidneys stimulates the release of renin – an enzyme which catalyses the production of the potent vasopressor angiotensin. Angiotensin and its metabolites cause further vasocontriction, and stimulate increased secretion of the steroid aldosterone from the adrenal glands. This promotes salt and fluid retention at the kidneys, also increasing the blood volume.

- The chronically high levels of circulating neuroendocrine hormones such as catecholamines, renin, angiotensin, and aldosterone affects the myocardium directly, causing structural remodelling of the heart over the long term. Many of these remodelling effects seem to be mediated by transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta), which is a common downstream target of the signal transduction cascade initiated by catecholamines[4] and angiotensin II,[5] and also by epidermal growth factor (EGF), which is a target of the signaling pathway activated by aldosterone[6]

- The increased peripheral resistance and greater blood volume place further strain on the heart and accelerates the process of damage to the myocardium. Vasoconstriction and fluid retention produce an increased hydrostatic pressure in the capillaries. This shifts the balance of forces in favour of interstitial fluid formation as the increased pressure forces additional fluid out of the blood, into the tissue. This results in edema (fluid build-up) in the tissues. In right-sided heart failure this commonly starts in the ankles where venous pressure is high due to the effects of gravity (although if the patient is bed-ridden, fluid accumulation may begin in the sacral region.) It may also occur in the abdominal cavity, where the fluid build-up is called ascites. In left-sided heart failure edema can occur in the lungs - this is called cardiogenic pulmonary edema. This reduces spare capacity for ventilation, causes stiffening of the lungs and reduces the efficiency of gas exchange by increasing the distance between the air and the blood. The consequences of this are shortness of breath, orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.

Right Heart Failure as a Result of Left Heart Failure

[edit | edit source]- The hypoxia caused by pulmonary edema causes vasoconstriction in the pulmonary circulation, which results in pulmonary hypertension. Since the right ventricle generates far lower pressures than the left ventricle (approximately 20 mmHg versus around 120 mmHg, respectively, in the healthy individual) but nonetheless generates cardiac output exactly equal to the left ventricle, this means that a small increase in pulmonary vascular resistance causes a large increase in amount of work the right ventricle must perform.

- Other mechanisms of right heart failure are mediated by neurohormonal activation.[7]

- Mechanical effects may also contribute. As the left ventricle distends, the intraventricular septum bows into the right ventricle, decreasing the filling capacity of the right ventricle.

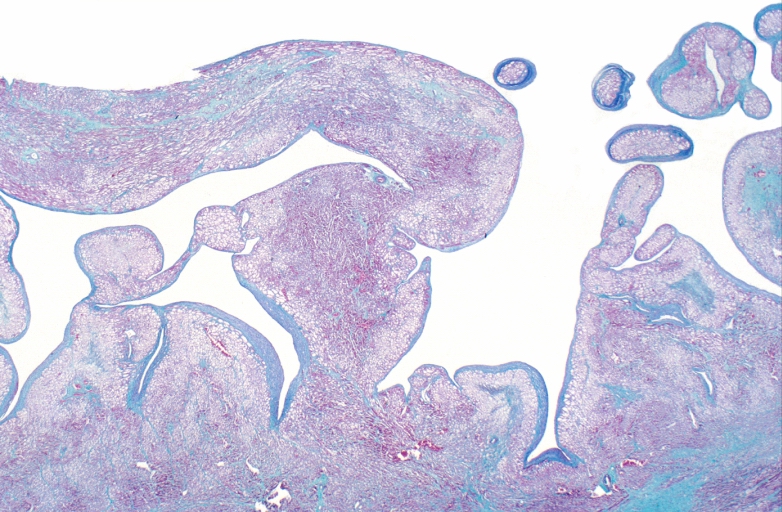

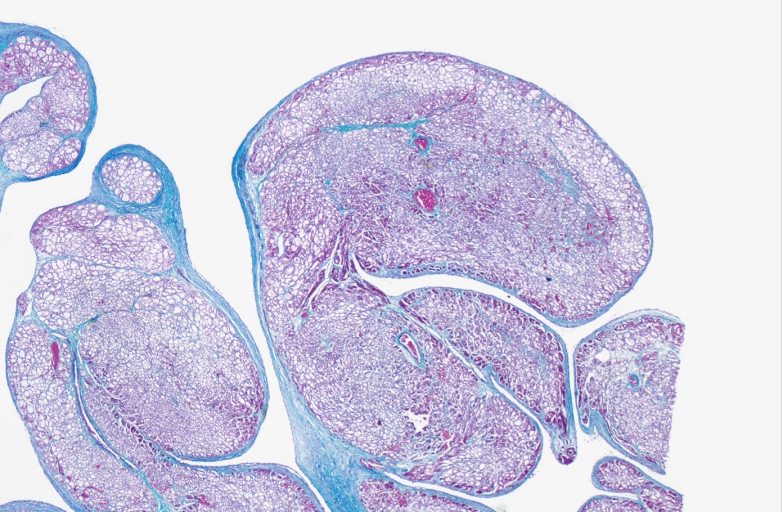

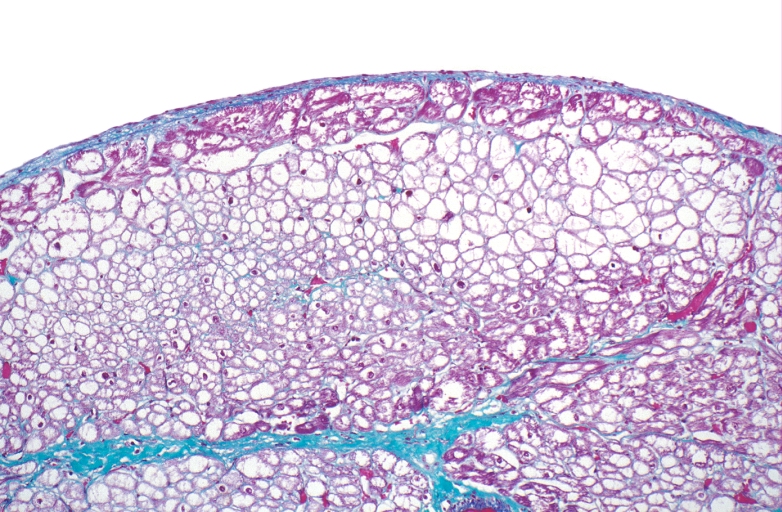

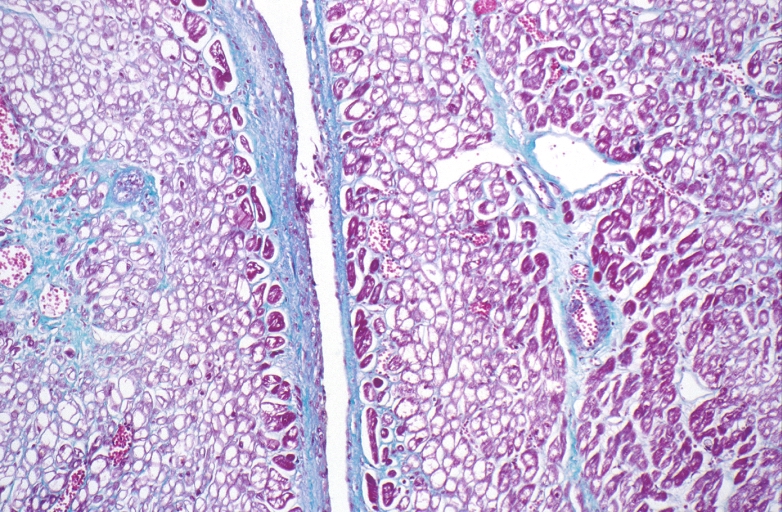

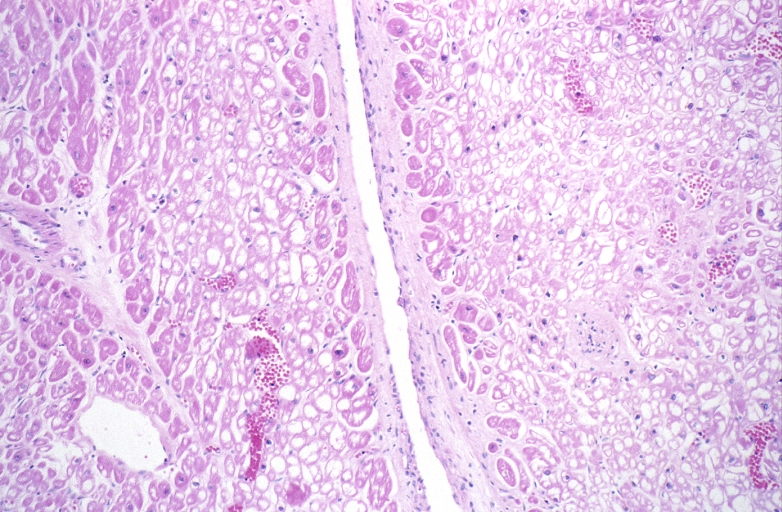

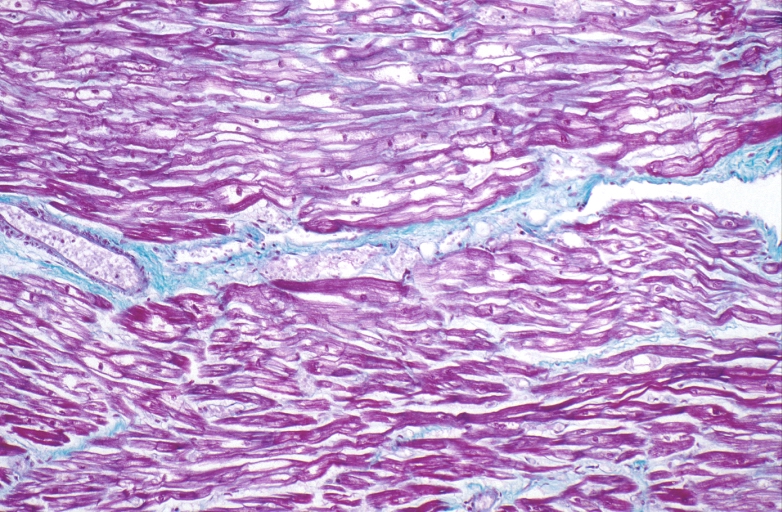

Microscopic Pathology

[edit | edit source]-

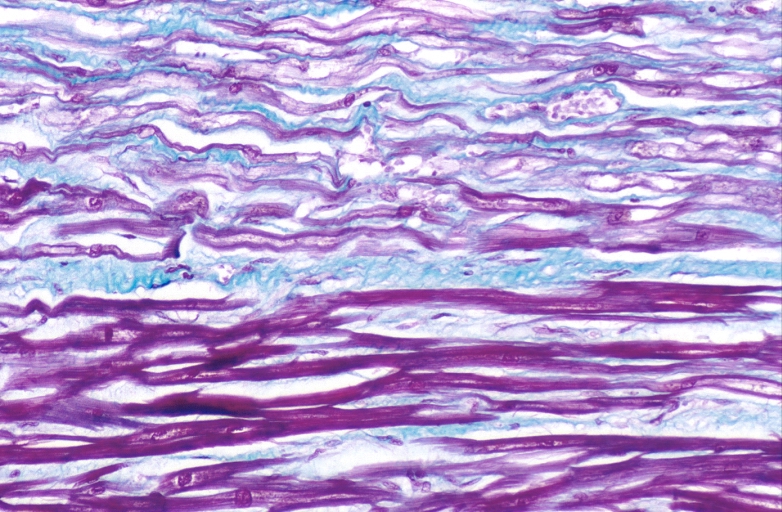

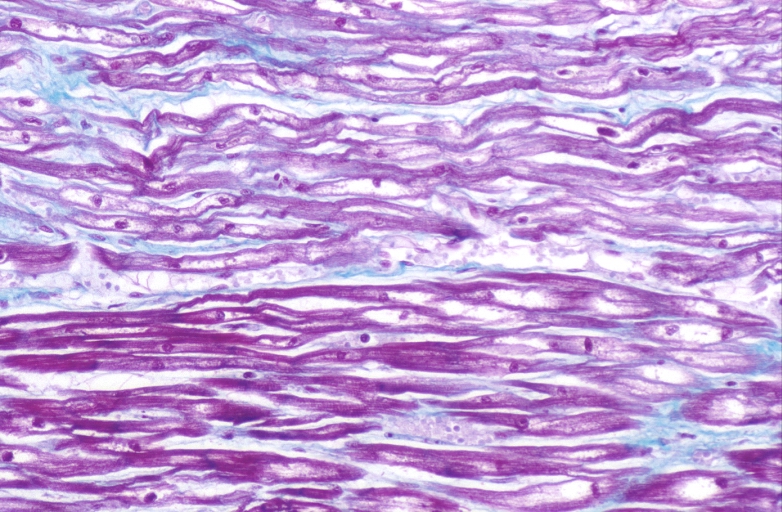

HEART: Congestive heart failure, hydropic change

-

HEART: Congestive heart failure, hydropic change

-

HEART: Congestive heart failure, hydropic change

-

HEART: Congestive heart failure, hydropic change

-

HEART: Congestive heart failure, hydropic change

-

HEART: Congestive heart failure, hydropic change

-

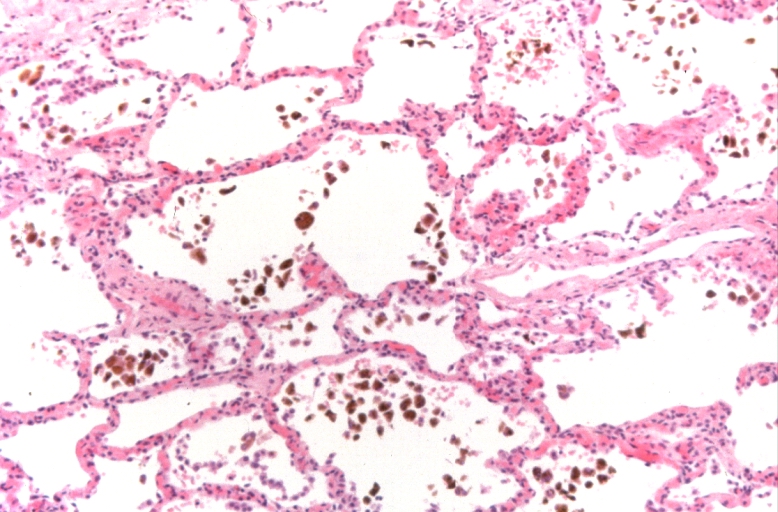

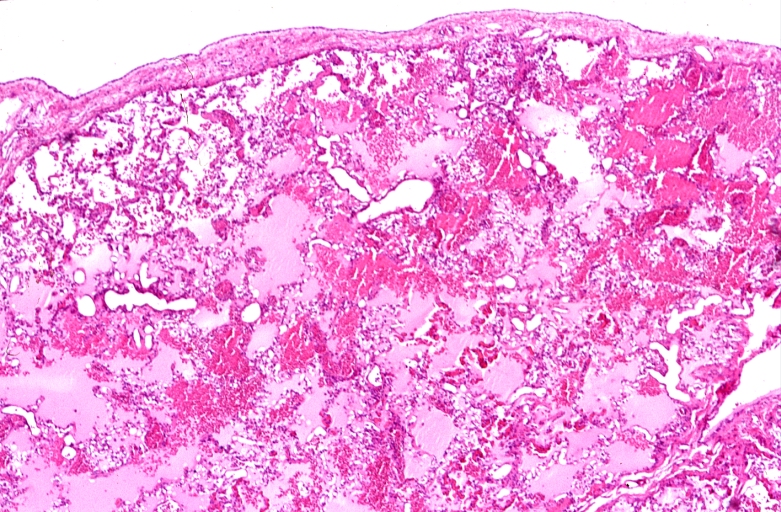

Lung, congestion, heart failure cells (hemosiderin laden macrophages)

-

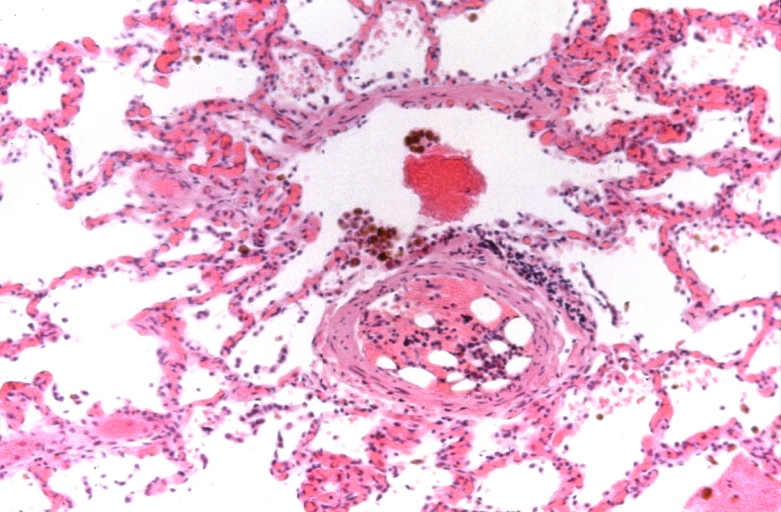

Lung, Congestive Heart Failure, bone marrow embolus

-

Lung, pulmonary edema in patient with congestive heart failure due to heart transplant rejection

-

HEART: Congestive heart failure, hydropic change

-

HEART Congestive heart failure, hydropic change

-

Spleen, congestion, congestive heart failure

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ Template:GPnotebook

- ↑ Boron and Boulpaep 2005 Medical Physiology Updated Edition p533 ISBN 0-7216-3256-4

- ↑ Rang HP (2003). Pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 127. ISBN 0-443-07145-4.

- ↑ Shigeyama J, Yasumura Y, Sakamoto A; et al. (2005). "Increased gene expression of collagen Types I and III is inhibited by beta-receptor blockade in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy". Eur. Heart J. 26 (24): 2698–705. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi492. PMID 16204268. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Tsutsui H, Matsushima S, Kinugawa S; et al. (2007). "Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker attenuates myocardial remodeling and preserves diastolic function in diabetic heart" (– Scholar search). Hypertens. Res. 30 (5): 439–49. doi:10.1291/hypres.30.439. PMID 17587756. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) [dead link] - ↑ Krug AW, Grossmann C, Schuster C; et al. (2003). "Aldosterone stimulates epidermal growth factor receptor expression". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (44): 43060–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.M308134200. PMID 12939263. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Hunter JG, Boon NA, Davidson S, Colledge NR, Walker B (2006). Davidson's principles & practice of medicine. Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. p. 544. ISBN 0-443-10057-8.

KSF

KSF