Diabetes mellitus cardiovascular disease

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 5 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 5 min

|

Diabetes mellitus Main page |

|

Patient Information |

|---|

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-In-Chief: Priyamvada Singh, M.B.B.S. [2]; Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [3]

Overview[edit | edit source]

Cardiovascular complications of diabetes include both microvascular disease, such as retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy and macrovascular disease such as coronary artery disease and stroke.

Cardiovascular Disease[edit | edit source]

Chronic elevation of blood glucose level leads to damage of blood vessels (angiopathy). The endothelial cells lining the blood vessels take in more glucose than normal, since they don't depend on insulin. They then form more surface glycoproteins than normal, and cause the basement membrane to grow thicker and weaker. In diabetes, the resulting problems are grouped under "microvascular disease" (due to damage to small blood vessels) and "macrovascular disease" (due to damage to the arteries).

Microvascular Disease[edit | edit source]

The damage to small blood vessels leads to a microangiopathy, which can cause one or more of the following:

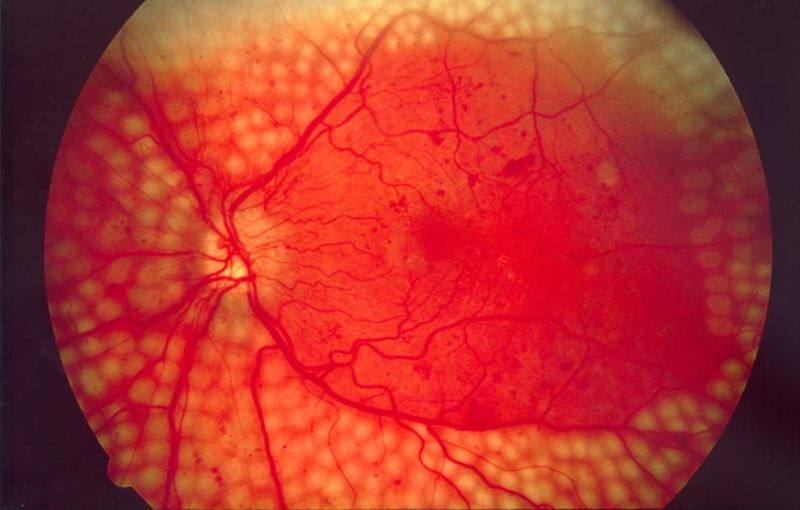

- Diabetic retinopathy, growth of friable and poor-quality new blood vessels in the retina as well as macular edema (swelling of the macula), which can lead to severe vision loss or blindness. Retinal damage (from microangiopathy) makes it the most common cause of blindness among non-elderly adults in the US.

- Diabetic neuropathy, abnormal and decreased sensation, usually in a 'glove and stocking' distribution starting with the feet but potentially in other nerves, later often fingers and hands. When combined with damaged blood vessels this can lead to diabetic foot (see below). Other forms of diabetic neuropathy may present as mononeuritis or autonomic neuropathy. Diabetic amyotrophy is muscle weakness due to neuropathy.

- Diabetic nephropathy, damage to the kidney which can lead to chronic renal failure, eventually requiring dialysis. Diabetes mellitus is the most common cause of adult kidney failure worldwide in the developed world.

Macrovascular Disease[edit | edit source]

Macrovascular disease leads to cardiovascular disease, to which accelerated atherosclerosis is a contributor:

- Coronary artery disease, leading to angina or myocardial infarction ("heart attack")

- Stroke (mainly the ischemic type)

- Peripheral vascular disease, which contributes to intermittent claudication (exertion-related leg and foot pain) as well as diabetic foot.

- Diabetic myonecrosis ('muscle wasting')

Diabetic foot, often due to a combination of neuropathy and arterial disease, may cause skin ulcer and infection and, in serious cases, necrosis and gangrene. It is why diabetics are prone to leg and foot infections and why it takes longer for them to heal from leg and foot wounds. It is the most common cause of adult amputation, usually of toes and or feet, in the developed world.

Carotid artery stenosis does not occur more often in diabetes, and there appears to be a lower prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm. However, diabetes does cause higher morbidity, mortality and operative risks with these conditions.[1]

Cardiovascular Disease and Gender[edit | edit source]

While population based studies have shown a higher risk of cardiovascular disorders in men , women with diabetes are faced with a higher risk of dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disorders than men with diabetes. This seems to be irrespective of menopause status. This could be partially explained by a higher fat tissue and a hyperactive immune system in women with diabetes.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death (DO NOT EDIT) [2][edit | edit source]

Recommendations for Endocrine Disorders and Diabetes[edit | edit source]

| Class I |

| "1. The management of ventricular arrhythmias secondary to endocrine disorders should address the electrolyte (potassium, magnesium, and calcium) imbalance and the treatment of the underlying endocrinopathy. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

| "2. Persistent life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias that develop in patients with endocrine disorders should be treated in the same manner that such arrhythmias are treated in patients with other diseases, including use of ICD and pacemaker implantation as required in those who are receiving chronic optimal medical therapy and who have reasonable expectation of survival with a good functional status for more than 1 y. (Level of Evidence: C)" |

| "3. Patients with diabetes with ventricular arrhythmias should generally be treated in the same manner as patients without diabetes. (Level of Evidence: A)" |

Primary Prevention[edit | edit source]

ACC/AHA Guidelines- ADA/AHA/ACCF Aspirin for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in People With Diabetes [3] (DO NOT EDIT)[edit | edit source]

| “ |

|

” |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Weiss J, Sumpio B (2006). "Review of prevalence and outcome of vascular disease in patients with diabetes mellitus". Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 31 (2): 143–50. PMID 16203161.

- ↑ Zipes DP, Camm AJ, Borggrefe M, Buxton AE, Chaitman B, Fromer M; et al. (2006). "ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society". Circulation. 114 (10): e385–484. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.178233. PMID 16935995.

- ↑ Pignone M, Alberts MJ, Colwell JA, Cushman M, Inzucchi SE, Mukherjee D; et al. (2010). "Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in people with diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association, a scientific statement of the American Heart Association, and an expert consensus document of the American College of Cardiology Foundation". Circulation. 121 (24): 2694–701. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181e3b133. PMID 20508178.

KSF

KSF