Head

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 5 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 5 min

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

In anatomy, the head of an animal is the rostral part (from anatomical position) that usually comprises the brain, eyes, ears, nose, and mouth (all of which aid in various sensory functions, such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste). Some very simple animals may not have a head, but many bilaterally symmetric forms do.

Anatomy in humans[edit | edit source]

Bones of the head[edit | edit source]

The skull is divided into the cranium (all the skull bones except the mandible) and the mandible (or jawbone). One feature that distinguishes mammals and non-mammals is that there are also three ear bones (called ossicles):

These ossicles are important components in the sense of hearing in mammals. Other animals have a single bone that is usually called the columella.

The cranium can be divided into a skull cap (or calvarium) and base. The cranium consists of several bones which fuse together at junctions called sutures. Several sutures join to form a pterion. This process of bone fusion occurs in utero to protect the most important organ in the body, the brain. Although most fusing is complete before birth, there are large areas of fibrous tissue (called fontanelles) where fusion is incomplete until puberty. The fontanelle above the forehead in newborns and young children is particularly easy to identify by touch. The adult cranium is separated into several bones, several of which are mirrored on the right and left sides of the skull. Descriptions of these bones often use terms of anatomical position to more accurately depict how the bones relate to each other:

- two maxillae (one on each side of the head) that cover the inferior and medial to the eye socket (or orbit)

- two zygomatic bones, inferior and lateral to the orbit

- two temporal bones, covering an area where the ears are located

- a single frontal bone, superior to the orbit

- two parietal bones, posterior to the frontal bone and superior to the temporal bone

- an occipital bone at the back of the head

- several more internal bones which are not easily seen which are

- a sphenoid bone

- an ethmoid bone

- two lacrimal bones

- two nasal bones

- two palatine bones

- two nasal conchae

- a vomer

There are a total of 14 bones in the face.

The rest of the skull is the mandible, a bone attached to the cranium at the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). This important joint allows the mandible to move, using the TMJ as a pivot to achieve actions such as chewing (mastication), eating, and speech.

When viewed from below (inferiorly) the skull contains several holes (or foramina), the largest of which is the foramen magnum through which the spinal cord passes. Other holes allow for the passage of arteries, veins, and nerves (the cranial nerves). When the skull cap (or calvarium) is removed, the base of the skull is viewed from above, there are three clear impressions or fossa. The most anterior of these is the anterior cranial fossa, where, amongst other things, upon which the frontal lobe of the brain lies. The butterfly-shaped middle cranial fossa is the second most anterior depression, the wings of which serve as a base for the brain's temporal lobes. The body of the butterfly houses an important structure, the sella turcica (Latin for Turkish saddle), which encapsulates the pituitary gland, one of the major organs of the endocrine system. The posterior cranial fossa is where the foramen magnum is located and where the posterior lobe of the brain and the cerebellum lie.

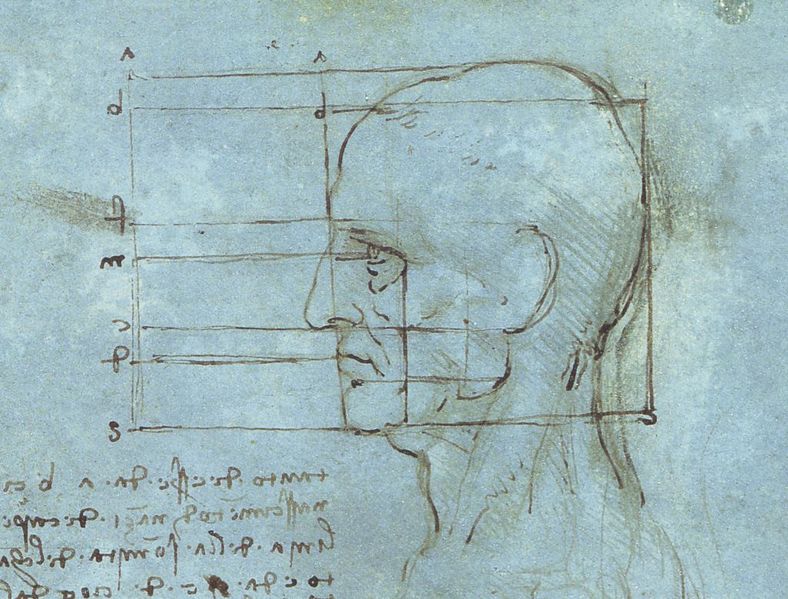

Anatomy of the face[edit | edit source]

Anatomically, the face stretches from the point of the chin to the roots of hair. The skin of the face is quite pliable and loose. Owing to the face's lack of deep fascia, facial wounds tend to bleed rather freely.

There are five orifices on the face: two for the eyes, two nostrils, and the mouth.

The blood supply to the face and indeed the most of the scalp comes mainly from the external carotid artery.

The sensory supply to the face comes solely from the trigeminal nerve (the fifth cranial nerve), so named because it branches into three divisions. The ophthalmic division covers an area above the eyes, including the forehead and most of the nose. The maxillary division covers an area below the eyes but above the mouth, including the cheeks and some of the nose. The mandibular division covers an area below the mouth and to the sides of the cheeks to the ears. This area does not cover the mandibular angle (the protrusion on the jawbone), which is innervated by the second cervical spinal nerve.

The muscles in the face include the nasal muscles, zygomatic muscles, muscles of mastication (chewing), and those of facial expression. The frontal part of the large occipitofrontalis muscle contains two parts, the occipital part (or occipitalis) and the frontal part (or frontalis). Although the two muscles are separate and supplied by different nerves, they are connected by fibromuscular tissue (called the galea aponeurotica) that stretches across the top half of the head to form the scalp. This arrangement of two different muscles attached together constitutes a digastric muscle, the actions of which are to wrinkle the forehead and raise the eyebrow. The muscle is attached to the skin of the forehead and eyebrow in front (anteriorly) and to the superior nuchal line in back (posteriorly). The frontal belly of the digastric muscle is supplied by the temporal nerve, a branch of the facial nerve (the seventh cranial nerve) while the occipital belly is supplied by another branch of the facial nerve, the posterior auricular nerve.

Anatomy in non-humans[edit | edit source]

Bilateral symmetry[edit | edit source]

The very simplest animals do not have a head, but many bilaterally symmetric forms do. In vertebrates the contents of the head are protected by an enclosure of bone called the skull, which is attached to the spine.

Clothing[edit | edit source]

In many cultures, covering the head is seen as a sign of respect. Often, some or all of the head must be covered and veiled when entering holy places, or places of prayer. For many centuries, women in Europe, the Middle East, and parts of Asia, have covered their hair as a sign of modesty. This trend has changed drastically in Europe in the 20th Century, although is still observed in other parts of the world. In addition, a number of religious paths require men to wear specific head clothing- such as the Jewish skullcap, or the sikh turban; or Muslim women, who cover their hair, ears and neck with a scarf.

Different headpieces can also signify status, origin, religious/spiritual beliefs, social grouping, occupation, and fashion choices.

Pseudoscientific study of the human head[edit | edit source]

Because the human head is the location of the thinking organ, it has been the subject of intense study. Some of the early modern research on the human head by German physician Franz Joseph Gall has resulted in the pseudoscience of phrenology, which reached its peak in the 19th century. It attributes character traits and mental abilities to the shape of the head. The measurement of the human head and skull, known as craniometry, gained popularity at the same time. Some, notably in Nazi Germany, have used these measurements and other comparative research as the underpinnings of racist, pseudoscientific theories.

The procedure of trepanation has also been advocated and practiced for pseudoscientific reasons.

References[edit | edit source]

- Campbell, Bernard Grant. Human Evolution: An Introduction to Man's Adaptations (4th edition), ISBN 0-202-02042-8

See also[edit | edit source]

- Headless

- Head and neck anatomy

External links[edit | edit source]

Template:Head and neck general

als:Kopf

ar:رأس

br:Penn

bg:Глава

cs:Hlava (člověk)

cy:Pen

da:Hoved

pdc:Kopp

de:Kopf

eo:Kapo

eu:Buru

gd:Ceann

gl:Cabeza

io:Kapo

id:Kepala

ia:Capite

is:Höfuð

it:Testa

he:ראש

kg:Ntu

ht:Tèt

la:Caput

ln:Motó

jbo:stedu

ml:തല

nl:Hoofd (anatomie)

no:Hode

qu:Uma

scn:Testa

simple:Head

sl:Glava

su:Sirah

fi:Pää

sv:Huvud

te:తల

tl:ulo

uk:Голова

yi:קאפ

tl:Ulo

KSF

KSF