Intracranial pressure

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 21 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 21 min

| Intracranial pressure | |

| |

|---|---|

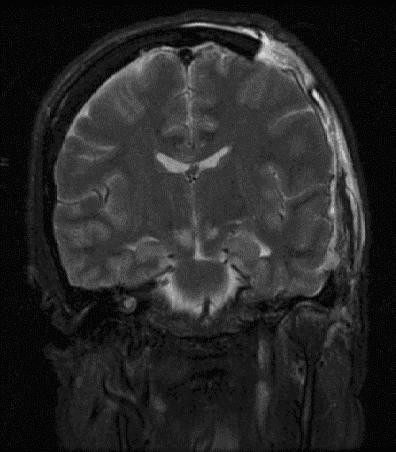

| Severely high ICP can cause herniation. |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Luke Rusowicz-Orazem, B.S., Sabeeh Islam, MBBS[2]

Overview[edit | edit source]

Intracranial pressure, (ICP), is the pressure exerted by three structures inside the cranium; brain parenchyma, CSF and blood. The norma ICP is 10-15 mmHg and is usually maintained by equilibrium of the intracranial contents. Intracranial hypertension ( IH), is elevation of the pressure in the cranium. It typically occurs when the ICP is >20 mmHg. Hans Queckenstedt's was the first person to use lumbar needle for ICP monitoring. Intracranial hypertension is generally categorized as acute or chronic. The Monro-Kellie hypothesis explains the relationship between the contents of the cranium and intracranial pressure. It explains the underlying pathophysiology of elevated intracranial pressure or intracranial hypertension. Several pathophysiologic mechanisms are thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of Increased Intracaranial pressure (ICP) or Intracranial hypertension (ICH). All mechanisms eventually lead to brain injury from brain stem compression and decreased cerebral blood supply or ischemia. Increased Intracaranial pressure (ICP) or Intracranial hypertension (ICH) must be differentiated from other diseases that cause headache, nausea, vomiting and neurologic deficits such as tumor, abscess or space occupying lesion, venous sinus thrombosis, neck surgery, Obstructive hydrocephalus, meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, choroid plexus papilloma, and Malignant systemic hypertension. The diagnosis of Increased Intracaranial pressure (ICP) or Intracranial hypertension (ICH) is made when ICP is >20 mmHg. CT scan or MRI may be considered initial diagnostic investigations. Intracranial hypertension is considered to be emergency condition. Treatment includes resuscitative measures and specific directed therapy. Resuscitative measures include oxygen, blood pressure and ICP monitoring, osmotic diuresis, head elevation up to 30 degrees, therapeutic hypothermia and seizure prophylaxis.

Historical Perspective[edit | edit source]

- In 1950s, therapeutic hypothermia (goal core temperature of 32-34C) was first introduced as a treatment for brain injury. [1]

- In early 1800s, the Monro-Kellie hypothesis and the CSF physiology was first introduced by Alexander Monro and George Kellie.

- Hans Queckenstedt's was the first person to use lumbar needle for ICP monitoring.

Classification[edit | edit source]

- Elevated intracranial pressure or Intracranial hypertension may be classified into two subtypes/groups:

- Acute

- Chronic

- Intracranial hypertension may also be classified as various stages:

- Stage 1: Minimal increases in ICP due to compensatory mechanisms

- Stage 2:

- Any change in volume greater than 100–120 mL

- Exhaustion of compensatory mechanisms

- Compromise of neuronal oxygenation and systemic arteriolar vasoconstriction to increase MAP and CP

- Stage 3:

- Sustained increased ICP

- Dramatic changes in ICP with small changes in volume

- The ICP approaches the MAP

Intracranial pressure, (ICP), is the pressure exerted by three structures inside the cranium; brain parenchyma, CSF and blood. The norma ICP is 10-15 mmHg and is usually maintained by equilibrium of the intracranial contents.

Intracranial hypertension ( IH), is elevation of the pressure in the cranium. It typically occurs when the ICP is >20 mmHg.

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Intracranial components and their proportions:[edit | edit source]

- Brain parenchyma volume: 1400 ml (80%)[2]

- CSF volume: 10 ml (10%)

- Blood volume: 10 ml (10%)

The Monro-Kellie Hypothesis:[edit | edit source]

- The Monro-Kellie hypothesis explains the relationship between the contents of the cranium and intracranial pressure. It explains the underlying pathophysiology of elevated intracranial pressure or intracranial hypertension.

- In normal physiological state, intracranial contents (the brain tissue, the blood, and the cerebrospinal fluid) maintain an equilibrium state and keep the ICP within normal range by acting as compensatory mechanisms for small volume changes.[3]

- Compensatory mechanisms are being exhausted by large volume changes, eventually causing significantly elevated intracranial pressures and potential herniation.[4]

Intracranial compliance:[edit | edit source]

- There is an inverse relationship between intracranial components and the compliance.

- Generally the normal compliance is maintained by compensatory mechanisms such as

- Increased CSF reabsorption via thecal sac

- Increased venoconstriction to decrease cerebral venous flow

- Decreased cerebral venous flow via increased extracranial drainage

Cerebral Blood Flow (Ohm's Law):[edit | edit source]

- Cerebral blood flow is generally assessed by subtracting jugular venous pressure from carotid arterial pressure and dividing by cerebrovascular resistance, as follows:[5][6][7]

- CBF = (CAP - JVP) ÷ CVR

- Cerebral perfusion is assessed by cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP). CPP is calculated by subtracting ICP from mean arterial pressure, as follows:

- CPP = MAP - ICP[8]

- In normal physiological states, ICP and CPP is maintained by autoregulation.[4]

Several pathophysiologic mechanisms are thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of Increased Intracaranial pressure (ICP) or Intracranial hypertension (ICH). All mechanisms eventually lead to brain injury from brain stem compression and decreased cerebral blood supply or ischemia. These mechanisms are as follows:

- Mass effect

- It can occur secondary to brain tumor, contusions, subdural or epidural hematoma, or abscess[9]

- Cerebral edema or Generalized brain swelling

- It can occur secondary to ischemic-anoxia states, hypertensive encephalopathy, pseudotumor cerebri, and hypercarbia.

- These conditions tend to decrease the cerebral perfusion pressure but with minimal tissue shifts.

- Increase in venous pressure

- Secondary to venous sinus thrombosis, heart failure, neck surgery or obstruction of superior mediastinal or jugular veins.

- Obstruction to CSF flow

- Secondary to hydrocephalus, extensive meningeal disease (e.g., infectious, carcinomatous, granulomatous, or hemorrhagic), or obstruction in cerebral convexities and superior sagittal sinus (decreased absorption).

- Increased CSF production

- Meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or choroid plexus tumor.

- Increased cerebral blood flow (CBF)

- Increased CBF is generally seen in conditions associated with hypercapnia and hypoxia

- Drugs

- Idiopathic

- Mass effect

Causes[edit | edit source]

Common Causes[edit | edit source]

- Aneurysm

- Arnold-chiari malformation

- Behçet's disease

- Brain tumor

- Cerebral edema

- Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis

- Choroid plexus tumor

- Chronic kidney disease

- Colloid cyst of third ventricle

- Contusions

- Crouzon craniofacial dysostosis

- Cushing's syndrome

- Dural arteriovenous fistula

- Encephalitis

- Epidural haemorrhage

- Epidural hematoma

- Erdheim-chester disease

- Excess cerebrospinal fluid

- Head trauma

- Hydrocephalus

- Hypertensive brain hemorrhage

- Hypertensive encephalopathy

- Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

- Insulin like growth factor 1

- Intracranial granuloma

- Intracranial haemorrhage

- Intraventricular hemorrhage

- Meningioma

- Meningitis

- Meningoencephalitis

- Multiple hamartoma syndrome

- Obstruction of superior mediastinal veins

- Obstruction of jugular veins

- Status epilepticus

- Stroke

- Subarachnoid haemorrhage

- Subdural haemorrhage

- Subdural hematoma

- Vasculitis

- Venous sinus thrombosis

Differential Diagnosis of Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP)[edit | edit source]

- Increased Intracaranial pressure (ICP) or Intracranial hypertension (ICH) must be differentiated from other diseases that cause headache, nausea, vomiting and neurologic deficits such as tumor, abscess or space occupying lesion, venous sinus thrombosis, neck surgery, Obstructive hydrocephalus, meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, choroid plexus papilloma, and Malignant systemic hypertension.

Differentiating Increased Intracaranial pressure (ICP) or Intracranial hypertension (ICH) from Other Diseases on the Basis of Seizure, Visual disturbance, and Constitutional Symptoms[edit | edit source]

On the basis of seizure, visual disturbance, and constitutional symptoms, meningioma must be differentiated from oligodendroglioma, astrocytoma, hemangioblastoma, pituitary adenoma, schwannoma, primary CNS lymphoma, medulloblastoma, ependymoma, craniopharyngioma, pinealoma, AV malformation, brain aneurysm, bacterial brain abscess, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, hydatid cyst, CNS cryptococcosis, CNS aspergillosis, and brain metastasis.

| Diseases | Clinical manifestations | Para-clinical findings | Gold standard |

Additional findings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Physical examination | |||||||||

| Lab Findings | MRI | Immunohistopathology | ||||||||

| Head- ache |

Seizure | Visual disturbance | Constitutional | Focal neurological deficit | ||||||

| Adult primary brain tumors | ||||||||||

| Meningioma [10][11][12] |

+ | +/− | +/− | − | + | − |

|

|

| |

| Glioblastoma multiforme [13][14][15] |

+ | +/− | +/− | − | + | − |

|

|

| |

| Oligodendroglioma [16][17][18] |

+ | + | +/− | − | + | − |

|

|

| |

| Hemangioblastoma [19][20][21][22] |

+ | +/− | +/− | − | + | − |

|

| ||

| Pituitary adenoma [23][24][15] |

− | − | + Bitemporal hemianopia | − | − |

|

|

|

| |

| Schwannoma [25][26][27][28] |

− | − | − | − | + | − |

|

|

| |

| Primary CNS lymphoma [29][30] |

+ | +/− | +/− | − | + | − |

|

|

| |

| Childhood primary brain tumors | ||||||||||

| Pilocytic astrocytoma [31][32][33] |

+ | +/− | +/− | − | + | − |

|

|

| |

| Medulloblastoma [34][35][36] |

+ | +/− | +/− | − | + | − |

|

|

| |

| Ependymoma [37][15] |

+ | +/− | +/− | − | + | − |

|

|

| |

| Craniopharyngioma [38][39][40][15] |

+ | +/− | + Bitemporal hemianopia | − | + |

|

|

|

| |

| Pinealoma [41][42][43] |

+ | +/− | +/− | − | + vertical gaze palsy |

|

|

|

| |

| Vascular | ||||||||||

| AV malformation [44][45][15] |

+ | + | +/− | − | +/− | − |

|

| ||

| Brain aneurysm [46][47][48][49][50] |

+ | +/− | +/− | − | +/− | − |

|

|

|

|

| Infectious | ||||||||||

| Bacterial brain abscess [51][52] |

+ | +/− | +/− | + | + |

|

|

|

|

|

| Tuberculosis [53][15][54] |

+ | +/− | +/− | + | + |

|

|

|

|

|

| Toxoplasmosis [55][56] |

+ | +/− | +/− | − | + |

|

|

|

|

|

| Hydatid cyst [57][15] |

+ | +/− | +/− | +/− | + |

|

|

|

|

|

| CNS cryptococcosis [58] |

+ | +/− | +/− | + | + |

|

|

|

|

|

| CNS aspergillosis [59] |

+ | +/− | +/− | + | + |

|

|

|

|

|

| Other | ||||||||||

| Brain metastasis [60][15] |

+ | +/− | +/− | + | + | − |

|

|

|

|

ABBREVIATIONS

CNS=Central nervous system, AV=Arteriovenous, CSF=Cerebrospinal fluid, NF-2=Neurofibromatosis type 2, MEN-1=Multiple endocrine neoplasia, GFAP=Glial fibrillary acidic protein, HIV=Human immunodeficiency virus, BhCG=Human chorionic gonadotropin, ESR=Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, AFB=Acid fast bacilli, MRA=Magnetic resonance angiography, CTA=CT angiography

Epidemiology and Demographics[edit | edit source]

- The prevalence of intracranial hypertension is approximately 1.0 per 100,000 individuals worldwide.

Gender[edit | edit source]

- Idiopathic ICH is more prevalent among women of childbearing age.

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

- Common risk factors in the development of Increased Intracaranial pressure (ICP) or Intracranial hypertension (ICH) include underlying pathologies such as; mass lesions, abscesses, and hematomas.

- Other risk factors include

- Obesity

- Chronic hypertension

- Women of childbearing age

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis[edit | edit source]

- Early clinical features include nausea, vomiting, and confusion.

- If left untreated, patients may progress to have severe neurologic consequences such as brain herniation, brain death, respiratory depression, brain infections, coma and death.

- Common complications of intracranial hypertension include brain herniation and neurologic deficits.

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic Criteria[edit | edit source]

- The diagnosis of Increased Intracaranial pressure (ICP) or Intracranial hypertension (ICH) is made when ICP is >20 mmHg.

History and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

- Symptoms of elevated intracranial pressure may include the following:

- Headache

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Hyperventilation (due to injury to brain stem or tegmentum is damaged.[61]

- Changes in your behavior

- Weakness or problems with moving or talking

- Lack of energy or sleepiness

- Seizure

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

- Physical examination may be remarkable for

- Ocular palsies (abducens palsy)

- Periorbital bruising[62]

- Altered level of consciousness

- Papilledema[63]

- Pupillary dilatation

- Cushing's triad ( Elevated systolic blood pressure, a widened pulse pressure, bradycardia, and an abnormal respiratory pattern.

- Cheyne-Stokes respiration

- Bulging of fontanels in infants

Laboratory Findings[edit | edit source]

- There are no specific laboratory findings associated with Increased Intracaranial pressure (ICP) or Intracranial hypertension (ICH).

Electrocardiogram[edit | edit source]

- There are no ECG findings associated with Increased Intracaranial pressure (ICP) or Intracranial hypertension (ICH).

X-ray[edit | edit source]

- There are no x-ray findings associated with Increased Intracaranial pressure (ICP) or Intracranial hypertension (ICH).

CT scan[edit | edit source]

- CT scan may be helpful in the diagnosis of Increased Intracaranial pressure (ICP) or Intracranial hypertension (ICH).

- Findings on CT scan suggestive of Increased Intracaranial pressure (ICP) or Intracranial hypertension (ICH) include presence of mass lesions, midline shift or hemorrhage.

- CT scan is particularly helpful for people with acute rise in ICP.

MRI[edit | edit source]

- MR venography (MRV) is preferred over MRI for the diagnosis of cerebral venous thrombosis

- MRI has a greater sensitivity to detect subtle intracranial masses (eg, gliomatosis cerebri) and meningeal-based pathologies and should be done if no contraindications (eg, pacemakers, metallic clips in head, metallic foreign bodies) present

Other Diagnostic Studies[edit | edit source]

Other diagnostic studies for Increased Intracaranial pressure (ICP) or Intracranial hypertension (ICH) include invasive and non-invasive ICP monitoring, particularly preferred in patients with no CT or MRI findings, at risk of developing increased ICP, and comatosed.

- Invasive ICP monitoring usually involves 4 anatomic sites:[64][65][66][67][68]

- Noninvasive devices still need further large randomized trials to prove their clinical efficacy. They are not used in clinical practice but are still under investigation and include:[75][76]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Medical Therapy[edit | edit source]

- The management of intracranial hypertension is generally directed towards treating the cause/etiology of the raised intracranial pressure.

- Intracranial hypertension is considered a medical emergency and the management includes emergent resuscitative as well as specific treatment.

Resuscitation:[edit | edit source]

General principles for resuscitation include:[83][84][85][86][87][88][89]

- Maintain oxygen

- Head elevation

- Hyperventilation to achieve a PaCO2 of 26-30 mmHg

- Osmotic diuresis with intravenous mannitol and Lasix

- Appropriate sedation, if patient requires intubation. Propofol is considered to be the preferred agent.

- Therapeutic hypothermia to achieve a low metabolic state

- Appropriate choice of fluids to achieve euvolemic state. Avoid hypotonic agents

- Allow permissive hypertension. Treat hypertension only when CPP >120 mmHg and ICP >20 mmHg

- Seizure prophylaxis with anticonvulsant therapy.[90]

Other therapies for intracranial hypertension:[edit | edit source]

- Osmotic diuresis can be achieved by hypertonic saline bolus or mannitol. Hypertonic saline is usually considered to be more effective compared to mannitol for acute ICP reduction. Mannitol can be given as a bolus of 1 g/kg when prepared as 20% solution. The dose is usually repeated every 6-8 hours. It should be used cautiously in patients with renal insufficiency. Intravenous Lasix (0.5 to 1 mg/kg) is usually given with mannitol.[91][92]

- Glucocorticoids are usually preferred when the underlying etiologies brain tumor are underlying CNS infection. Their use is contraindicated in head injury, cerebral infarction and intracranial hemorrhage.[93]

- Phenobarbital is considered to have a neuroprotective effect by decreasing brain metabolism. It is given as a loading dose of 5 to 20 mg/kg, followed by 1 to 4 mg/kg per hour. EEG monitoring is used to guide therapy. A burst suppression seen on EEG indicates maximal dosing.[94]

Surgery[edit | edit source]

Surgical options for persistent intracranial hypertension include

- Surgical evacuation

- CSF drainage via ventriculostomy

- CSF is usually drained at a rate of 1 to 2 mL/minute for 2 to 3 minutes. The procedure is repeated after every 2 to 3 minutes, until ICP is less than 20mmHg

- Decompressive craniectomy[95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103]

Prevention[edit | edit source]

- Effective measures for the primary prevention of intracranial hypertension include early detection of underlying intracranial etiology such as tumor or congenital deformities.

- Once diagnosed and successfully treated, patients with intracranial hypertension are followed up every 6 months to 1 year with a head CT scan to prevent secondary complications.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Welch K (May 1980). "The intracranial pressure in infants". J. Neurosurg. 52 (5): 693–9. doi:10.3171/jns.1980.52.5.0693. PMID 7373397.

- ↑ Whedon JM, Glassey D (2009). "Cerebrospinal fluid stasis and its clinical significance". Altern Ther Health Med. 15 (3): 54–60. PMC 2842089. PMID 19472865.

- ↑ Bruce DA, Alavi A, Bilaniuk L, Dolinskas C, Obrist W, Uzzell B (February 1981). "Diffuse cerebral swelling following head injuries in children: the syndrome of "malignant brain edema"". J. Neurosurg. 54 (2): 170–8. doi:10.3171/jns.1981.54.2.0170. PMID 7452330.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Aldrich EF, Eisenberg HM, Saydjari C, Luerssen TG, Foulkes MA, Jane JA, Marshall LF, Marmarou A, Young HF (March 1992). "Diffuse brain swelling in severely head-injured children. A report from the NIH Traumatic Coma Data Bank". J. Neurosurg. 76 (3): 450–4. doi:10.3171/jns.1992.76.3.0450. PMID 1738026.

- ↑ Strandgaard S, Paulson OB (June 1989). "Cerebral blood flow and its pathophysiology in hypertension". Am. J. Hypertens. 2 (6 Pt 1): 486–92. doi:10.1093/ajh/2.6.486. PMID 2757806.

- ↑ Strandgaard S, Andersen GS, Ahlgreen P, Nielsen PE (1984). "Visual disturbances and occipital brain infarct following acute, transient hypotension in hypertensive patients". Acta Med Scand. 216 (4): 417–22. PMID 6516910.

- ↑ Enevoldsen EM, Jensen FT (May 1978). "Autoregulation and CO2 responses of cerebral blood flow in patients with acute severe head injury". J. Neurosurg. 48 (5): 689–703. doi:10.3171/jns.1978.48.5.0689. PMID 641549.

- ↑ Lassen NA, Agnoli A (October 1972). "The upper limit of autoregulation of cerebral blood flow--on the pathogenesis of hypertensive encepholopathy". Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 30 (2): 113–6. doi:10.3109/00365517209081099. PMID 4640619.

- ↑ Levin HS, Aldrich EF, Saydjari C, Eisenberg HM, Foulkes MA, Bellefleur M, Luerssen TG, Jane JA, Marmarou A, Marshall LF (September 1992). "Severe head injury in children: experience of the Traumatic Coma Data Bank". Neurosurgery. 31 (3): 435–43, discussion 443–4. doi:10.1227/00006123-199209000-00008. PMID 1407426.

- ↑ Zee CS, Chin T, Segall HD, Destian S, Ahmadi J (June 1992). "Magnetic resonance imaging of meningiomas". Semin. Ultrasound CT MR. 13 (3): 154–69. PMID 1642904.

- ↑ Shibuya M (2015). "Pathology and molecular genetics of meningioma: recent advances". Neurol. Med. Chir. (Tokyo). 55 (1): 14–27. doi:10.2176/nmc.ra.2014-0233. PMID 25744347.

- ↑ Begnami MD, Palau M, Rushing EJ, Santi M, Quezado M (September 2007). "Evaluation of NF2 gene deletion in sporadic schwannomas, meningiomas, and ependymomas by chromogenic in situ hybridization". Hum. Pathol. 38 (9): 1345–50. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2007.01.027. PMC 2094208. PMID 17509660.

- ↑ Sathornsumetee S, Rich JN, Reardon DA (November 2007). "Diagnosis and treatment of high-grade astrocytoma". Neurol Clin. 25 (4): 1111–39, x. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2007.07.004. PMID 17964028.

- ↑ Pedersen CL, Romner B (January 2013). "Current treatment of low grade astrocytoma: a review". Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 115 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.07.002. PMID 22819718.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 Mattle, Heinrich (2017). Fundamentals of neurology : an illustrated guide. Stuttgart New York: Thieme. ISBN 9783131364524.

- ↑ Smits M (2016). "Imaging of oligodendroglioma". Br J Radiol. 89 (1060): 20150857. doi:10.1259/bjr.20150857. PMC 4846213. PMID 26849038.

- ↑ Wesseling P, van den Bent M, Perry A (June 2015). "Oligodendroglioma: pathology, molecular mechanisms and markers". Acta Neuropathol. 129 (6): 809–27. doi:10.1007/s00401-015-1424-1. PMC 4436696. PMID 25943885.

- ↑ Kerkhof M, Benit C, Duran-Pena A, Vecht CJ (2015). "Seizures in oligodendroglial tumors". CNS Oncol. 4 (5): 347–56. doi:10.2217/cns.15.29. PMC 6082346. PMID 26478444.

- ↑ Lonser RR, Butman JA, Huntoon K, Asthagiri AR, Wu T, Bakhtian KD, Chew EY, Zhuang Z, Linehan WM, Oldfield EH (May 2014). "Prospective natural history study of central nervous system hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease". J. Neurosurg. 120 (5): 1055–62. doi:10.3171/2014.1.JNS131431. PMC 4762041. PMID 24579662.

- ↑ Hussein MR (October 2007). "Central nervous system capillary haemangioblastoma: the pathologist's viewpoint". Int J Exp Pathol. 88 (5): 311–24. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2613.2007.00535.x. PMC 2517334. PMID 17877533.

- ↑ Lee SR, Sanches J, Mark AS, Dillon WP, Norman D, Newton TH (May 1989). "Posterior fossa hemangioblastomas: MR imaging". Radiology. 171 (2): 463–8. doi:10.1148/radiology.171.2.2704812. PMID 2704812.

- ↑ Perks WH, Cross JN, Sivapragasam S, Johnson P (March 1976). "Supratentorial haemangioblastoma with polycythaemia". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 39 (3): 218–20. PMID 945331.

- ↑ Kucharczyk W, Davis DO, Kelly WM, Sze G, Norman D, Newton TH (December 1986). "Pituitary adenomas: high-resolution MR imaging at 1.5 T". Radiology. 161 (3): 761–5. doi:10.1148/radiology.161.3.3786729. PMID 3786729.

- ↑ Syro LV, Scheithauer BW, Kovacs K, Toledo RA, Londoño FJ, Ortiz LD, Rotondo F, Horvath E, Uribe H (2012). "Pituitary tumors in patients with MEN1 syndrome". Clinics (Sao Paulo). 67 Suppl 1: 43–8. PMC 3328811. PMID 22584705.

- ↑ Donnelly, Martin J.; Daly, Carmel A.; Briggs, Robert J. S. (2007). "MR imaging features of an intracochlear acoustic schwannoma". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 108 (12). doi:10.1017/S0022215100129056. ISSN 0022-2151.

- ↑ Feany MB, Anthony DC, Fletcher CD (May 1998). "Nerve sheath tumours with hybrid features of neurofibroma and schwannoma: a conceptual challenge". Histopathology. 32 (5): 405–10. PMID 9639114.

- ↑ Chen H, Xue L, Wang H, Wang Z, Wu H (July 2017). "Differential NF2 Gene Status in Sporadic Vestibular Schwannomas and its Prognostic Impact on Tumour Growth Patterns". Sci Rep. 7 (1): 5470. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-05769-0. PMID 28710469.

- ↑ Hardell, Lennart; Hansson Mild, Kjell; Sandström, Monica; Carlberg, Michael; Hallquist, Arne; Påhlson, Anneli (2003). "Vestibular Schwannoma, Tinnitus and Cellular Telephones". Neuroepidemiology. 22 (2): 124–129. doi:10.1159/000068745. ISSN 0251-5350.

- ↑ Chinn RJ, Wilkinson ID, Hall-Craggs MA, Paley MN, Miller RF, Kendall BE, Newman SP, Harrison MJ (December 1995). "Toxoplasmosis and primary central nervous system lymphoma in HIV infection: diagnosis with MR spectroscopy". Radiology. 197 (3): 649–54. doi:10.1148/radiology.197.3.7480733. PMID 7480733.

- ↑ Paulus, Werner (1999). "Classification, Pathogenesis and Molecular Pathology of Primary CNS Lymphomas". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 43 (3): 203–208. doi:10.1023/A:1006242116122. ISSN 0167-594X.

- ↑ Sathornsumetee S, Rich JN, Reardon DA (November 2007). "Diagnosis and treatment of high-grade astrocytoma". Neurol Clin. 25 (4): 1111–39, x. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2007.07.004. PMID 17964028.

- ↑ Pedersen CL, Romner B (January 2013). "Current treatment of low grade astrocytoma: a review". Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 115 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.07.002. PMID 22819718.

- ↑ Mattle, Heinrich (2017). Fundamentals of neurology : an illustrated guide. Stuttgart New York: Thieme. ISBN 9783131364524.

- ↑ Dorwart, R H; Wara, W M; Norman, D; Levin, V A (1981). "Complete myelographic evaluation of spinal metastases from medulloblastoma". Radiology. 139 (2): 403–408. doi:10.1148/radiology.139.2.7220886. ISSN 0033-8419.

- ↑ Fruehwald-Pallamar, Julia; Puchner, Stefan B.; Rossi, Andrea; Garre, Maria L.; Cama, Armando; Koelblinger, Claus; Osborn, Anne G.; Thurnher, Majda M. (2011). "Magnetic resonance imaging spectrum of medulloblastoma". Neuroradiology. 53 (6): 387–396. doi:10.1007/s00234-010-0829-8. ISSN 0028-3940.

- ↑ Burger, P. C.; Grahmann, F. C.; Bliestle, A.; Kleihues, P. (1987). "Differentiation in the medulloblastoma". Acta Neuropathologica. 73 (2): 115–123. doi:10.1007/BF00693776. ISSN 0001-6322.

- ↑ Yuh, E. L.; Barkovich, A. J.; Gupta, N. (2009). "Imaging of ependymomas: MRI and CT". Child's Nervous System. 25 (10): 1203–1213. doi:10.1007/s00381-009-0878-7. ISSN 0256-7040.

- ↑ Brunel H, Raybaud C, Peretti-Viton P, Lena G, Girard N, Paz-Paredes A, Levrier O, Farnarier P, Manera L, Choux M (September 2002). "[Craniopharyngioma in children: MRI study of 43 cases]". Neurochirurgie (in French). 48 (4): 309–18. PMID 12407316.

- ↑ Prabhu, Vikram C.; Brown, Henry G. (2005). "The pathogenesis of craniopharyngiomas". Child's Nervous System. 21 (8–9): 622–627. doi:10.1007/s00381-005-1190-9. ISSN 0256-7040.

- ↑ Kennedy HB, Smith RJ (December 1975). "Eye signs in craniopharyngioma". Br J Ophthalmol. 59 (12): 689–95. PMC 1017436. PMID 766825.

- ↑ Ahmed SR, Shalet SM, Price DA, Pearson D (September 1983). "Human chorionic gonadotrophin secreting pineal germinoma and precocious puberty". Arch. Dis. Child. 58 (9): 743–5. PMID 6625640.

- ↑ Sano, Keiji (1976). "Pinealoma in Children". Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1159/000119602. ISSN 1016-2291.

- ↑ Baggenstoss, Archie H. (1939). "PINEALOMAS". Archives of Neurology And Psychiatry. 41 (6): 1187. doi:10.1001/archneurpsyc.1939.02270180115011. ISSN 0096-6754.

- ↑ Kucharczyk, W; Lemme-Pleghos, L; Uske, A; Brant-Zawadzki, M; Dooms, G; Norman, D (1985). "Intracranial vascular malformations: MR and CT imaging". Radiology. 156 (2): 383–389. doi:10.1148/radiology.156.2.4011900. ISSN 0033-8419.

- ↑ Fleetwood, Ian G; Steinberg, Gary K (2002). "Arteriovenous malformations". The Lancet. 359 (9309): 863–873. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07946-1. ISSN 0140-6736.

- ↑ Chapman, Arlene B.; Rubinstein, David; Hughes, Richard; Stears, John C.; Earnest, Michael P.; Johnson, Ann M.; Gabow, Patricia A.; Kaehny, William D. (1992). "Intracranial Aneurysms in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 327 (13): 916–920. doi:10.1056/NEJM199209243271303. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ↑ Castori M, Voermans NC (October 2014). "Neurological manifestations of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome(s): A review". Iran J Neurol. 13 (4): 190–208. PMC 4300794. PMID 25632331.

- ↑ Schievink, W. I.; Raissi, S. S.; Maya, M. M.; Velebir, A. (2010). "Screening for intracranial aneurysms in patients with bicuspid aortic valve". Neurology. 74 (18): 1430–1433. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dc1acf. ISSN 0028-3878.

- ↑ Germain DP (May 2017). "Pseudoxanthoma elasticum". Orphanet J Rare Dis. 12 (1): 85. doi:10.1186/s13023-017-0639-8. PMC 5424392. PMID 28486967.

- ↑ Farahmand M, Farahangiz S, Yadollahi M (October 2013). "Diagnostic Accuracy of Magnetic Resonance Angiography for Detection of Intracranial Aneurysms in Patients with Acute Subarachnoid Hemorrhage; A Comparison to Digital Subtraction Angiography". Bull Emerg Trauma. 1 (4): 147–51. PMC 4789449. PMID 27162847.

- ↑ Haimes, AB; Zimmerman, RD; Morgello, S; Weingarten, K; Becker, RD; Jennis, R; Deck, MD (1989). "MR imaging of brain abscesses". American Journal of Roentgenology. 152 (5): 1073–1085. doi:10.2214/ajr.152.5.1073. ISSN 0361-803X.

- ↑ Brouwer, Matthijs C.; Tunkel, Allan R.; McKhann, Guy M.; van de Beek, Diederik (2014). "Brain Abscess". New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (5): 447–456. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1301635. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ↑ Morgado, Carlos; Ruivo, Nuno (2005). "Imaging meningo-encephalic tuberculosis". European Journal of Radiology. 55 (2): 188–192. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2005.04.017. ISSN 0720-048X.

- ↑ Be NA, Kim KS, Bishai WR, Jain SK (March 2009). "Pathogenesis of central nervous system tuberculosis". Curr. Mol. Med. 9 (2): 94–9. PMC 4486069. PMID 19275620.

- ↑ Chinn RJ, Wilkinson ID, Hall-Craggs MA, Paley MN, Miller RF, Kendall BE, Newman SP, Harrison MJ (December 1995). "Toxoplasmosis and primary central nervous system lymphoma in HIV infection: diagnosis with MR spectroscopy". Radiology. 197 (3): 649–54. doi:10.1148/radiology.197.3.7480733. PMID 7480733.

- ↑ Helton KJ, Maron G, Mamcarz E, Leventaki V, Patay Z, Sadighi Z (November 2016). "Unusual magnetic resonance imaging presentation of post-BMT cerebral toxoplasmosis masquerading as meningoencephalitis and ventriculitis". Bone Marrow Transplant. 51 (11): 1533–1536. doi:10.1038/bmt.2016.168. PMID 27348541.

- ↑ Taslakian B, Darwish H (September 2016). "Intracranial hydatid cyst: imaging findings of a rare disease". BMJ Case Rep. 2016. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-216570. PMC 5030532. PMID 27620198.

- ↑ McCarthy M, Rosengart A, Schuetz AN, Kontoyiannis DP, Walsh TJ (July 2014). "Mold infections of the central nervous system". N. Engl. J. Med. 371 (2): 150–60. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1216008. PMC 4840461. PMID 25006721.

- ↑ McCarthy M, Rosengart A, Schuetz AN, Kontoyiannis DP, Walsh TJ (July 2014). "Mold infections of the central nervous system". N. Engl. J. Med. 371 (2): 150–60. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1216008. PMC 4840461. PMID 25006721.

- ↑ Pope WB (2018). "Brain metastases: neuroimaging". Handb Clin Neurol. 149: 89–112. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-811161-1.00007-4. PMC 6118134. PMID 29307364.

- ↑ Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedsgo - ↑ Hadjikoutis S, Carroll C, Plant GT (August 2004). "Raised intracranial pressure presenting with spontaneous periorbital bruising: two case reports". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 75 (8): 1192–3. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.016006. PMC 1739150. PMID 15258230.

- ↑ Binder DK, Lyon R, Manley GT (April 2004). "Transcranial motor evoked potential recording in a case of Kernohan's notch syndrome: case report". Neurosurgery. 54 (4): 999–1002, discussion 1002–3. doi:10.1227/01.neu.0000115674.15497.09. PMID 15046669.

- ↑ Rosner MJ, Rosner SD, Johnson AH (December 1995). "Cerebral perfusion pressure: management protocol and clinical results". J. Neurosurg. 83 (6): 949–62. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.6.0949. PMID 7490638.

- ↑ Lane PL, Skoretz TG, Doig G, Girotti MJ (December 2000). "Intracranial pressure monitoring and outcomes after traumatic brain injury". Can J Surg. 43 (6): 442–8. PMC 3695200. PMID 11129833.

- ↑ Bulger EM, Nathens AB, Rivara FP, Moore M, MacKenzie EJ, Jurkovich GJ (August 2002). "Management of severe head injury: institutional variations in care and effect on outcome". Crit. Care Med. 30 (8): 1870–6. doi:10.1097/00003246-200208000-00033. PMID 12163808.

- ↑ Mauritz W, Steltzer H, Bauer P, Dolanski-Aghamanoukjan L, Metnitz P (July 2008). "Monitoring of intracranial pressure in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: an Austrian prospective multicenter study". Intensive Care Med. 34 (7): 1208–15. doi:10.1007/s00134-008-1079-7. PMID 18365169.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 Bratton SL, Chestnut RM, Ghajar J, McConnell Hammond FF, Harris OA, Hartl R, Manley GT, Nemecek A, Newell DW, Rosenthal G, Schouten J, Shutter L, Timmons SD, Ullman JS, Videtta W, Wilberger JE, Wright DW (2007). "Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. VII. Intracranial pressure monitoring technology". J. Neurotrauma. 24 Suppl 1: S45–54. doi:10.1089/neu.2007.9989. PMID 17511545.

- ↑ Mayhall CG, Archer NH, Lamb VA, Spadora AC, Baggett JW, Ward JD, Narayan RK (March 1984). "Ventriculostomy-related infections. A prospective epidemiologic study". N. Engl. J. Med. 310 (9): 553–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM198403013100903. PMID 6694707.

- ↑ Holloway KL, Barnes T, Choi S, Bullock R, Marshall LF, Eisenberg HM, Jane JA, Ward JD, Young HF, Marmarou A (September 1996). "Ventriculostomy infections: the effect of monitoring duration and catheter exchange in 584 patients". J. Neurosurg. 85 (3): 419–24. doi:10.3171/jns.1996.85.3.0419. PMID 8751626.

- ↑ Ostrup RC, Luerssen TG, Marshall LF, Zornow MH (August 1987). "Continuous monitoring of intracranial pressure with a miniaturized fiberoptic device". J. Neurosurg. 67 (2): 206–9. doi:10.3171/jns.1987.67.2.0206. PMID 3598682.

- ↑ Gambardella G, d'Avella D, Tomasello F (November 1992). "Monitoring of brain tissue pressure with a fiberoptic device". Neurosurgery. 31 (5): 918–21, discussion 921–2. doi:10.1227/00006123-199211000-00014. PMID 1436417.

- ↑ Bochicchio M, Latronico N, Zappa S, Beindorf A, Candiani A (October 1996). "Bedside burr hole for intracranial pressure monitoring performed by intensive care physicians. A 5-year experience". Intensive Care Med. 22 (10): 1070–4. doi:10.1007/BF01699230. PMID 8923072.

- ↑ Miller JD, Bobo H, Kapp JP (August 1986). "Inaccurate pressure readings for subarachnoid bolts". Neurosurgery. 19 (2): 253–5. doi:10.1227/00006123-198608000-00012. PMID 3748354.

- ↑ Manno EM (January 1997). "Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography in the neurocritical care unit". Crit Care Clin. 13 (1): 79–104. doi:10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70297-9. PMID 9012577.

- ↑ Edouard AR, Vanhille E, Le Moigno S, Benhamou D, Mazoit JX (February 2005). "Non-invasive assessment of cerebral perfusion pressure in brain injured patients with moderate intracranial hypertension". Br J Anaesth. 94 (2): 216–21. doi:10.1093/bja/aei034. PMID 15591334.

- ↑ Aaslid R, Markwalder TM, Nornes H (December 1982). "Noninvasive transcranial Doppler ultrasound recording of flow velocity in basal cerebral arteries". J. Neurosurg. 57 (6): 769–74. doi:10.3171/jns.1982.57.6.0769. PMID 7143059.

- ↑ Michaeli D, Rappaport ZH (June 2002). "Tissue resonance analysis; a novel method for noninvasive monitoring of intracranial pressure. Technical note". J. Neurosurg. 96 (6): 1132–7. doi:10.3171/jns.2002.96.6.1132. PMID 12066918.

- ↑ Moretti R, Pizzi B, Cassini F, Vivaldi N (December 2009). "Reliability of optic nerve ultrasound for the evaluation of patients with spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage". Neurocrit Care. 11 (3): 406–10. doi:10.1007/s12028-009-9250-8. PMID 19636971.

- ↑ Moretti R, Pizzi B (January 2009). "Optic nerve ultrasound for detection of intracranial hypertension in intracranial hemorrhage patients: confirmation of previous findings in a different patient population". J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 21 (1): 16–20. doi:10.1097/ANA.0b013e318185996a. PMID 19098619.

- ↑ Sheeran P, Bland JM, Hall GM (March 2000). "Intraocular pressure changes and alterations in intracranial pressure". Lancet. 355 (9207): 899. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(99)02768-3. PMID 10752710.

- ↑ Han Y, McCulley TJ, Horton JC (August 2008). "No correlation between intraocular pressure and intracranial pressure". Ann. Neurol. 64 (2): 221–4. doi:10.1002/ana.21416. PMID 18570302.

- ↑ Procaccio F, Stocchetti N, Citerio G, Berardino M, Beretta L, Della Corte F, D'Avella D, Brambilla GL, Delfini R, Servadei F, Tomei G (March 2000). "Guidelines for the treatment of adults with severe head trauma (part I). Initial assessment; evaluation and pre-hospital treatment; current criteria for hospital admission; systemic and cerebral monitoring". J Neurosurg Sci. 44 (1): 1–10. PMID 10961490.

- ↑ Procaccio F, Stocchetti N, Citerio G, Berardino M, Beretta L, Della Corte F, D'Avella D, Brambilla GL, Delfini R, Servadei F, Tomei G (March 2000). "Guidelines for the treatment of adults with severe head trauma (part II). Criteria for medical treatment". J Neurosurg Sci. 44 (1): 11–8. PMID 10961491.

- ↑ Davella D, Brambilla GL, Delfini R, Servadei F, Tomei G, Procaccio F, Stocchetti N, Citerio G, Berardino M, Beretta L, Della Corte F (March 2000). "Guidelines for the treatment of adults with severe head trauma (part III). Criteria for surgical treatment". J Neurosurg Sci. 44 (1): 19–24. PMID 10961492.

- ↑ Robinson N, Clancy M (November 2001). "In patients with head injury undergoing rapid sequence intubation, does pretreatment with intravenous lignocaine/lidocaine lead to an improved neurological outcome? A review of the literature". Emerg Med J. 18 (6): 453–7. doi:10.1136/emj.18.6.453. PMC 1725712. PMID 11696494.

- ↑ Smith ER, Madsen JR (June 2004). "Neurosurgical aspects of critical care neurology". Semin Pediatr Neurol. 11 (2): 169–78. doi:10.1016/j.spen.2004.04.002. PMID 15259869.

- ↑ Smith ER, Madsen JR (June 2004). "Cerebral pathophysiology and critical care neurology: basic hemodynamic principles, cerebral perfusion, and intracranial pressure". Semin Pediatr Neurol. 11 (2): 89–104. doi:10.1016/j.spen.2004.04.001. PMID 15259863.

- ↑ Schmoker JD, Shackford SR, Wald SL, Pietropaoli JA (September 1992). "An analysis of the relationship between fluid and sodium administration and intracranial pressure after head injury". J Trauma. 33 (3): 476–81. doi:10.1097/00005373-199209000-00024. PMID 1404521.

- ↑ Gabor AJ, Brooks AG, Scobey RP, Parsons GH (June 1984). "Intracranial pressure during epileptic seizures". Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 57 (6): 497–506. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(84)90085-3. PMID 6202480.

- ↑ Bell BA, Smith MA, Kean DM, McGhee CN, MacDonald HL, Miller JD, Barnett GH, Tocher JL, Douglas RH, Best JJ (January 1987). "Brain water measured by magnetic resonance imaging. Correlation with direct estimation and changes after mannitol and dexamethasone". Lancet. 1 (8524): 66–9. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91908-8. PMID 2879175.

- ↑ Nath F, Galbraith S (July 1986). "The effect of mannitol on cerebral white matter water content". J. Neurosurg. 65 (1): 41–3. doi:10.3171/jns.1986.65.1.0041. PMID 3086519.

- ↑ Roberts I, Yates D, Sandercock P, Farrell B, Wasserberg J, Lomas G, Cottingham R, Svoboda P, Brayley N, Mazairac G, Laloë V, Muñoz-Sánchez A, Arango M, Hartzenberg B, Khamis H, Yutthakasemsunt S, Komolafe E, Olldashi F, Yadav Y, Murillo-Cabezas F, Shakur H, Edwards P (2004). "Effect of intravenous corticosteroids on death within 14 days in 10008 adults with clinically significant head injury (MRC CRASH trial): randomised placebo-controlled trial". Lancet. 364 (9442): 1321–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17188-2. PMID 15474134.

- ↑ Marshall LF, Shapiro HM, Rauscher A, Kaufman NM (1978). "Pentobarbital therapy for intracranial hypertension in metabolic coma. Reye's syndrome". Crit. Care Med. 6 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1097/00003246-197801000-00001. PMID 639524.

- ↑ Burkert W, Paver HD (1988). "[Decompressive trepanation in therapy refractory brain edema]". Zentralbl. Neurochir. (in German). 49 (4): 318–23. PMID 3075392.

- ↑ Burkert W, Plaumann H (1989). "[The value of large pressure-relieving trepanation in treatment of refractory brain edema. Animal experiment studies, initial clinical results]". Zentralbl. Neurochir. (in German). 50 (2): 106–8. PMID 2624017.

- ↑ Hatashita S, Hoff JT (October 1987). "The effect of craniectomy on the biomechanics of normal brain". J. Neurosurg. 67 (4): 573–8. doi:10.3171/jns.1987.67.4.0573. PMID 3655895.

- ↑ Hatashita S, Hoff JT (January 1988). "Biomechanics of brain edema in acute cerebral ischemia in cats". Stroke. 19 (1): 91–7. doi:10.1161/01.str.19.1.91. PMID 3336907.

- ↑ Rinaldi A, Mangiola A, Anile C, Maira G, Amante P, Ferraresi A (1990). "Hemodynamic effects of decompressive craniectomy in cold induced brain oedema". Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). 51: 394–6. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-9115-6_132. PMID 2089950.

- ↑ Gaab M, Knoblich OE, Fuhrmeister U, Pflughaupt KW, Dietrich K (1979). "Comparison of the effects of surgical decompression and resection of local edema in the therapy of experimental brain trauma. Investigation of ICP, EEG and cerebral metabolism in cats". Childs Brain. 5 (5): 484–98. doi:10.1159/000119844. PMID 477464.

- ↑ Dam Hieu P, Sizun J, Person H, Besson G (May 1996). "The place of decompressive surgery in the treatment of uncontrollable post-traumatic intracranial hypertension in children". Childs Nerv Syst. 12 (5): 270–5. doi:10.1007/BF00261809. PMID 8737804.

- ↑ Gower DJ, Lee KS, McWhorter JM (October 1988). "Role of subtemporal decompression in severe closed head injury". Neurosurgery. 23 (4): 417–22. doi:10.1227/00006123-198810000-00002. PMID 3200370.

- ↑ Guerra WK, Gaab MR, Dietz H, Mueller JU, Piek J, Fritsch MJ (February 1999). "Surgical decompression for traumatic brain swelling: indications and results". J. Neurosurg. 90 (2): 187–96. doi:10.3171/jns.1999.90.2.0187. PMID 9950487.

Additional Resources[edit | edit source]

- Monroe A. Observations on the structure and function of the nervous system, Edinburgh: Creech & Johnson; 1783.

- Kelly G. An account of the appearances observed in the dikssection of two of three individuals presumed to have perished in the storm of the 3rd, and whose bodies were deiscovered in the vicinity of the Leith on the morning of the 4th of November 1821, with some reflections on the pathology of the brain, Trans Med Chir Sci Edinb 1824;1:84–169.

External links[edit | edit source]

- Gruen P. 2002. "Monro-Kellie Model" Neurosurgery Infonet. USC Neurosurgery. Accessed January 4, 2007.

- National Guideline Clearinghouse. 2005. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. Firstgov. Accessed January 4, 2007.

KSF

KSF