Leprosy causes

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 5 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 5 min

|

Leprosy Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Leprosy causes On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Leprosy causes |

|

|

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: João André Alves Silva, M.D. [2]

Overview

[edit | edit source]Mycobacterium leprae is a gram-positive obligate intracellular, acid-fast bacillus, responsible for the development of leprosy, or Hansen's disease. This organism has a very slow growth and has a predilection to affect colder parts of the body, such as the skin, superficial nerves and upper respiratory mucous membranes. Although a route of transmission has not been absolutely defined yet, studies are pointing to a colonization of the dermis and respiratory mucosa of the infected patients. It is an uncommon bacteria, since it has only been noticed to infect and grow in some species of primates and in the nine-banded armadillo.[1]

Taxonomy

[edit | edit source]Bacteria; Actinobacteria; Actinobacteria; Actinobacteridae; Actinomycetales; Corynebacterineae; Mycobacteriaceae; Mycobacterium[2][3]

- Mycobacterium leprae

- Mycobacterium leprae 3125609

- Mycobacterium leprae 7935681

- Mycobacterium leprae Br4923

- Mycobacterium leprae Kyoto-2

- Mycobacterium leprae TN

- Mycobacterium lepromatosis

Biology

[edit | edit source]Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium lepromatosis are the causative agents of leprosy. M. lepromatosis is a relatively newly identified mycobacterium isolated from a fatal case of diffuse lepromatous leprosy in 2008.[4][5]

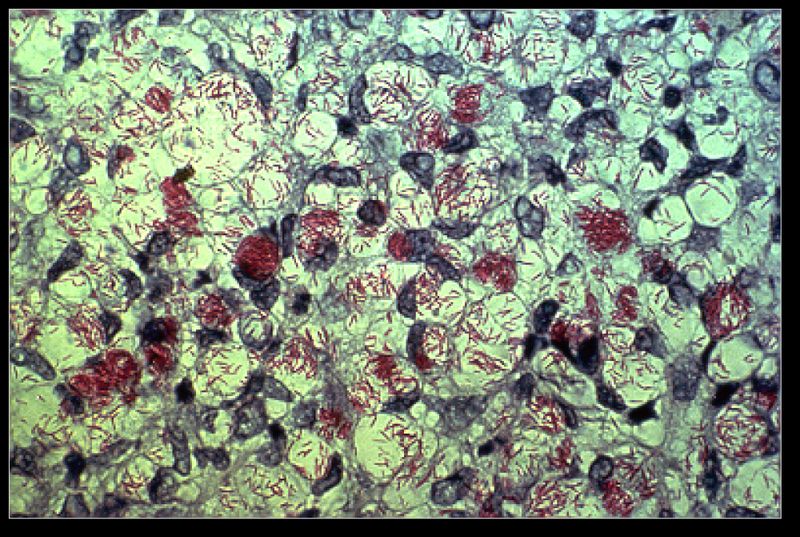

Mycobacterium leprae a gram-positive bacterium that causes leprosy (Hansen's disease).[5] It is an intracellular, pleomorphic, acid-fast bacterium.[6] M. leprae is a slow growing aerobic bacillus with a replication period that usually takes 11 - 13 days, surrounded by a characteristic waxy coating, unique to mycobacteria. In size and shape, it closely resembles Mycobacterium tuberculosis. [6]

Due to extensive loss of genes necessary for independent growth, M. leprae and M. lepromatosis are obligate intracellular parasites, and unculturable in the laboratory, a factor that leads to difficulty in definitively identifying the organism under a strict interpretation of Koch's postulates.[4][7] Due to the slow onset of leprosy and the absence of adequate immunological tools, it is not possible to know the specific incubation period for Mycobacterium leprae, however, according to multiple sources, this period may be settled between 3 to 10 years, since exposure to the viable bacteria.[1][8][9]

Studies performed in animal models show that the ideal temperature for growth of the M. leprae is at 27 - 33ºC, which is compatible with the preferred location in the body of this pathogen, the skin, mucous membranes and nerves close to the skin. This also explains the growth of bacteria in armadillos, since those animals have a core temperature of 34ºC.[10]

Origin

[edit | edit source]Leprosy, caused by Mycobacterium leprae is thought to have been originated in Middle Eastern countries, particularly in Egipt, around 2400 BC. Due to the lack of knowledge about the bacteria and treatment, the disease was then spread throughout the world. The Mycobacterium leprae would only be later discovered by G. H. Armauer Hansen in 1873, thereby being the first bacterium to be known as the cause of a human disease.[1]

Tropism

[edit | edit source]Mycobacterium leprae, unlike other mycobacteria, has tropism for cells of the peripheral nervous system, such as schwann cells, as well as for cells of the reticuloendothelial system.[11] This bacillus preferably infects macrophages, being collected in intracellular pockets called globi.[11]

Natural reservoir

[edit | edit source]Mycobacterium leprae is a bacillus with very specific needs for its growth. Until now, it has only been identified in 3 species of primates and in the nine-banded armadillo.[1][12]

While the causative organisms have been impossible to culture in vitro so far, it is possible to grow them in animals. Charles Shepard, chairman of the United States Leprosy Panel, successfully grew the organisms in the footpads of mice in 1960. This method was improved with the use of congenitally athymic mice (nude mice) in 1970 by Joseph Colson and Richard Hilson at St George's Hospital, London.

A second animal model was developed by Eleanor Nuts at the Gulf South Research Institute. Dr Storrs had worked on the nine-banded armadillo for her PhD, because this animal had a lower body temperature than humans and might therefore be a suitable animal model. These experiments proved unsuccessful, but additional work in 1970 with material provided by Chapman Binford, medical director of the Leonard's Wood Memorial, was successful. The papers describing this model led to a dispute of priority. Further controversy was generated when it was discovered that wild armadillos in Louisiana were naturally infected with leprosy.

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Bhat, Ramesh Marne; Prakash, Chaitra (2012). "Leprosy: An Overview of Pathophysiology". Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Infectious Diseases. 2012: 1–6. doi:10.1155/2012/181089. ISSN 1687-708X.

- ↑ "Taxonomy browser (Mycobacterium leprae)".

- ↑ "Taxonomy browser (Mycobacterium lepromatosis)".

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "New Leprosy Bacterium: Scientists Use Genetic Fingerprint To Nail 'Killing Organism'". ScienceDaily. 2008-11-28. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kenneth J. Ryan, C. George Ray, editors. (2004). Ryan KJ, Ray CG, ed. Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 451–3. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9. OCLC 52358530 61405904 Check

|oclc=value (help). - ↑ 6.0 6.1 McMurray DN (1996). "Mycobacteria and Nocardia.". In Baron S. et al., eds. Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ Bhattacharya S, Vijayalakshmi N, Parija SC (1 October 2002). "Uncultivable bacteria: Implications and recent trends towards identification". Indian journal of medical microbiology. 20 (4): 174–7. PMID 17657065.

- ↑ Han XY, Jessurun J (2013). "Severe leprosy reactions due to Mycobacterium lepromatosis". Am J Med Sci. 345 (1): 65–9. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31826af5fb. PMC 3529828. PMID 23111393.

- ↑ Gillis TP, Scollard DM, Lockwood DN (2011). "What is the evidence that the putative Mycobacterium lepromatosis species causes diffuse lepromatous leprosy?". Lepr Rev. 82 (3): 205–9. PMID 22125927.

- ↑ Scollard DM, Adams LB, Gillis TP, Krahenbuhl JL, Truman RW, Williams DL (2006). "The continuing challenges of leprosy". Clin Microbiol Rev. 19 (2): 338–81. doi:10.1128/CMR.19.2.338-381.2006. PMC 1471987. PMID 16614253.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Eichelmann, K.; González González, S.E.; Salas-Alanis, J.C.; Ocampo-Candiani, J. (2013). "Leprosy. An Update: Definition, Pathogenesis, Classification, Diagnosis, and Treatment". Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas (English Edition). 104 (7): 554–563. doi:10.1016/j.adengl.2012.03.028. ISSN 1578-2190.

- ↑ Lockwood, Diana; Moet, Fake J.; Schuring, Ron P.; Pahan, David; Oskam, Linda; Richardus, Jan Hendrik (2008). "The Prevalence of Previously Undiagnosed Leprosy in the General Population of Northwest Bangladesh". PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2 (2): e198. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000198. ISSN 1935-2735.

KSF

KSF