Lucid dream

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 16 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 16 min

|

WikiDoc Resources for Lucid dream |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Lucid dream Most cited articles on Lucid dream |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Lucid dream |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Lucid dream at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Lucid dream at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Lucid dream

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Lucid dream Discussion groups on Lucid dream Patient Handouts on Lucid dream Directions to Hospitals Treating Lucid dream Risk calculators and risk factors for Lucid dream

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Lucid dream |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [2]

A lucid dream is a dream in which the person is aware that he or she is dreaming while the dream is in progress. During lucid dreams, it is often possible to exert conscious control over the dream characters and environment, as well as to perform otherwise physically impossible feats. Lucid dreams are known to be extremely real and vivid.

A lucid dream can begin in one of two ways. A dream-initiated lucid dream (DILD) starts as a normal dream, and the dreamer eventually concludes that he or she is dreaming, or a wake-initiated lucid dream (WILD) occurs when the dreamer goes from a normal waking state directly into a dream state with no apparent lapse in consciousness.

Lucid dreaming has been researched scientifically, and its existence is well established.[1][2] Scientists such as Allan Hobson, with his neurophysiological approach to dream research, have helped to push the understanding of lucid dreaming into a less speculative realm.

Scientific history[edit | edit source]

The first book on lucid dreams to recognize their scientific potential was Celia Green's 1968 study Lucid Dreams. Reviewing the past literature, as well as new data from subjects of her own, Green analyzed the main characteristics of such dreams, and concluded that they were a category of experience quite distinct from ordinary dreams. She predicted that they would turn out to be associated with REM sleep. Green was also the first to link lucid dreams to the phenomenon of false awakenings.

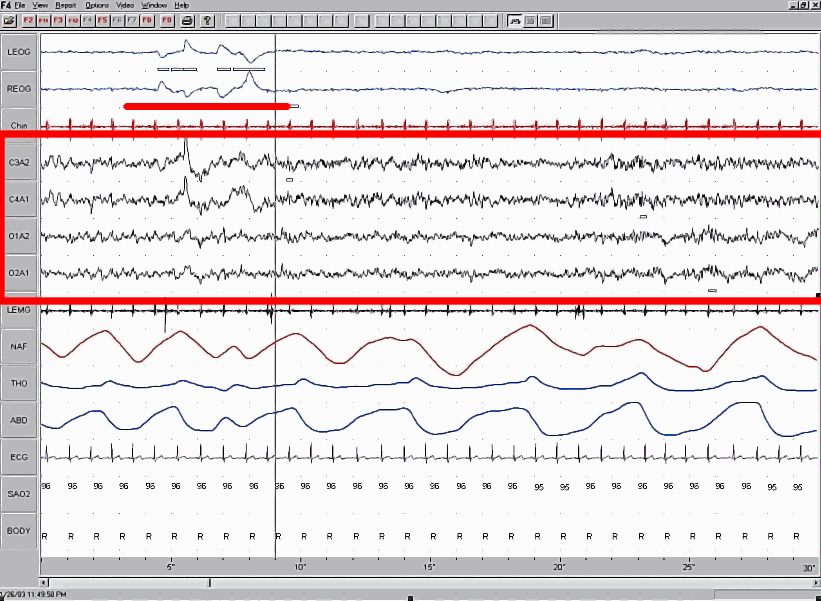

Philosopher Norman Malcolm's 1959 text Dreaming argued against the possibility of checking the accuracy of dream reports. However, the realisation that eye movements performed in dreams affected the dreamer's physical eyes provided a way to prove that actions agreed upon during waking life could be recalled and performed once lucid in a dream. The first evidence of this type was produced in the late 1970s by British parapsychologist Keith Hearne. A volunteer named Alan Worsley used eye movement to signal the onset of lucidity, which were recorded by a polysomnograph machine.

Hearne's results were not widely distributed. The first peer reviewed article was published some years later by Stephen LaBerge at Stanford University who had independently developed a similar technique as part of his doctoral dissertation.

During the 1980s, further scientific evidence to confirm the existence of lucid dreaming was produced as lucid dreamers were able to demonstrate to researchers that they were consciously aware of being in a dream state (again, primarily using eye movement signals). Additionally, techniques were developed which have been experimentally proven to enhance the likelihood of achieving this state.[3]

Research on techniques and effects of lucid dreaming continues at a number of universities and other centers such as LaBerge's The Lucidity Institute.

Research and clinical applications[edit | edit source]

Neurobiological model[edit | edit source]

Neuroscientist J. Allan Hobson has hypothesized as to what might be occurring in the brain while lucid. The first step to lucid dreaming is recognizing that one is dreaming. This recognition might occur in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex which is one of the few areas deactivated during REM sleep, and where working memory occurs. Once this area is activated and the recognition of dreaming occurs the dreamer must be cautious to let the dream delusions continue, but be conscious enough to recognize them. This process might be seen as the balance between reason and emotion. While maintaining this balance the amygdala and parahippocampal cortex might be less intensely activated.[4] To continue the intensity of the dream hallucinations it is expected the pons and the parieto-occipital junction cortex stay active. To verify this hypothesis it would be necessary to observe the brain during lucid dreaming using a method such as a PET scan, which captures a snapshot of the blood flow to the brain. No such experiment has yet been performed.[5]

Treatment for nightmares[edit | edit source]

People who suffer from nightmares would benefit from the ability to be aware they are dreaming. A pilot study was performed in 2006 that showed lucid dreaming treatment was successful in reducing nightmare frequency. This treatment consisted of exposure to the idea, mastery of the technique, and lucidity exercises. It was not clear what aspects of the treatment were responsible for the success of overcoming nightmares, though the treatment as a whole was successful.[6]

Perception of time while lucid dreaming[edit | edit source]

The rate that time passes while lucid dreaming has been shown to be about the same as while waking. In 1985 LaBerge performed a pilot study where lucid dreamers counted from one to ten (one-one thousand, two-one thousand, etc.) while dreaming, signaling the end of counting with a pre-arranged eye signal measured with Electrooculogram recording.[7] LaBerge's results were confirmed by German researchers in 2004. The German study, by Erlacher, D. & Schredl, M also studied motor activity and found that deep knee bends took 44% longer to perform while lucid dreaming.[8]

Near-death and out-of-body experiences[edit | edit source]

In a study of 14 lucid dreamers performed in 1991, people who perform wake initiated lucid dreams (WILD) reported experiences consistent with aspects of out-of-body experiences such as floating above their beds and the feeling of leaving their bodies.[9] Due to the phenomenological overlap between lucid dreams, near death experiences, and out of body experiences researchers say they believe a protocol could be developed to induce a lucid dream similar to a near death experience in the laboratory.[10]

Cultural history[edit | edit source]

Even though it has only come to the attention of the general public in the last few decades, lucid dreaming is not a modern discovery.

- In the fifth century, a very early example of lucid dreaming is in a letter written by St. Augustine of Hippo in 415 AD.[11]

- As early as the eighth century, Tibetan Buddhists were practicing a form of yoga supposed to maintain full waking consciousness while in the dream state.[12] This system is extensively discussed and explained in the book Dream Yoga and the Practice of Natural Light[13], one of the important messages of which has been the distinction between the Dzogchen meditation of Awareness and Dream Yoga or lucid dreaming. The Dzogchen Awareness meditation has also been referred to by the terms Rigpa Awareness, Contemplation, and Presence. Awareness during the sleep and dream states is associated with the Dzogchen practice of natural light, and lucid dreams may be a byproduct. In contrast, the more relative but still important experience of lucid dreaming is referred to as Dream yoga, and lucid dreaming is the goal. The lucidity experience, according to Buddhist teachers, assists in understanding the unreality of phenomena, which otherwise, during dream or the death experience, might be overwhelming.

- An early recorded lucid dreamer was the philosopher and physician Sir Thomas Browne (1605–1682). Browne was fascinated by the world of dreams and stated of his own ability to lucid dream in his Religio Medici: "... yet in one dream I can compose a whole Comedy, behold the action, apprehend the jests and laugh my self awake at the conceits thereof;"[14]

- Marquis d'Hervey de Saint-Denys was probably the first person to argue that it is possible for anyone to learn to dream consciously. In 1867, he published his book Les Reves et les Moyens de Les Diriger; Observations Pratiques (Dreams and How to Guide them; Practical Observations), in which he documented more than twenty years of his own research into dreams.

- The term "lucid dreaming" was coined by Dutch author and psychiatrist Frederik van Eeden in his 1913 article A Study of Dreams.[15] This book was highly anecdotal and not embraced by the scientific community. The term itself is considered by some to be a misnomer because it means much more than just "clear or vivid" dreaming.[16] A better term might have been "conscious dreaming". On the other hand, the term 'lucid' was used by van Eeden in its sense of 'having insight', as in the phrase 'a lucid interval' applied to someone in temporary remission from a psychosis, rather than as referring to the perceptual quality of the experience, which may or may not be clear and vivid. To that extent van Eeden's phrase may still be considered appropriate.

- In the 1950s the Senoi hunter-gatherers of Malaysia were reported to make extensive use of lucid dreaming to ensure mental health, although later studies refuted these claims.[17]

Induction methods[edit | edit source]

Many people report having experienced a lucid dream during their lives, often in childhood. Children seem to have lucid dreams more easily than adults. Although lucid dreaming is a conditioned skill,[18] achieving lucid dreams on a regular basis can be difficult and is uncommon, even with training. Over time, several techniques have been developed to achieve a lucid dreaming state intentionally. The following are common factors that influence lucid dreaming, and techniques that people use to help achieve a lucid dream:

Dream recall[edit | edit source]

Dream recall is simply the ability to remember dreams. Good dream recall is often described as the first step towards lucid dreaming. Better recall increases awareness of dreams in general; with limited dream recall any lucid dreams one has can be forgotten entirely.

The main technique used to improve dream recall is to keep a dream journal, writing down any dreams remembered the moment one awakes. It is important to record the dreams as quickly as possible as there is a strong tendency to forget what one has dreamt.[19] It is suggested that one's dream journal be recorded in the present tense. Describing an experience as if presently in it can help the writer to recall more accurately the events of their dream.

Dream recall can also be improved by staying still after waking up.[19] This may be something to do with REM atonia (the condition of REM sleep in which the motor neurons are not stimulated and thus the body's muscles do not move). If one purposely prevents motor neurons from firing immediately after waking from a dream, recalling said dream becomes easier. Similarly, if the dreamer changes positions in the night they may be able to recall certain events of their dream by testing different sleeping positions.

Mnemonic induction of lucid dreams (MILD)[edit | edit source]

The MILD technique is a common technique developed by Dr Stephen LaBerge, used to induce a lucid dream at will by setting an intention, while falling asleep, to remember to recognize that one is dreaming, or to remember to look for dream signs when one is in a dream.

Wake-back-to-bed (WBTB)[edit | edit source]

The wake-back-to-bed technique is often the easiest way to encourage a lucid dream. The method involves going to sleep tired and waking up five hours later. Then, focusing all thoughts on lucid dreaming, staying awake for an hour and going back to sleep while practicing the MILD method. A 60% success rate has been shown in research using this technique.[20] This is because the REM cycles get longer as the night goes on, and this technique takes advantage of the best REM cycle of the night. Because this REM cycle is longer and deeper, gaining lucidity during this time may result in a more lengthy lucid dream.[20]

Cycle adjustment technique (CAT)[edit | edit source]

The cycle adjustment technique, developed by Daniel Love, is an effective way to induce lucid dreaming. It involves adjusting one's sleep cycle to encourage awareness during the latter part of the sleep. First, the person wakes up 90 minutes before normal wake time until their sleep cycle begins to adjust. After this, the normal wake times and early wake times alternate. On the days with the normal wake times, the body is ready to wake up, and this increases alertness, making lucidity more likely.

Wake-initiation of lucid dreams (WILD)[edit | edit source]

The wake-initiated lucid dream "occurs when the sleeper enters REM sleep with unbroken self-awareness directly from the waking state".[21] There are many techniques aimed at entering a WILD. The key to these techniques is recognizing the hypnagogic stage, which is within the border of being awake and being asleep. If a person is successful in staying aware while this stage occurs, he or she will eventually enter the dream state while being fully aware that it is a dream.

There are key times at which this state is best entered; while success at night after being awake for a long time is very difficult, it is relatively easy after being awake for 15 or so minutes and in the afternoon during a nap. Techniques for inducing WILDs abound. Dreamers may count, envision themselves climbing or descending stairs, chant to themselves, explore elaborate, passive sexual fantasies, control their breathing, counting their breaths to keep their thoughts from drifting, concentrate on relaxing their body from their toes to their head, allow images to flow through their "mind's eye" and envision themselves jumping into the image, to maintain concentration and keep their mind awake, while still being calm enough to let their body sleep.

During the actual transition into the dream state, one is likely to experience sleep paralysis, including rapid vibrations,[9] a sequence of loud sounds and a feeling of twirling into another state of body awareness, "to drift off into another dimension". Also there is frequently a sensation of falling rapidly or dropping through the bed as one enters the dream state. After the transition there may be the sensation of entering a dark black room from which one can induce any dream scenario of one's choosing, simply by concentrating on it. The key to success is not to panic, especially during the transition, which can be quite sudden.

Induction devices[edit | edit source]

Lucid dream induction is possible by the use of a physical device. The general principle works by taking advantage of the natural phenomenon of incorporating external stimuli into one's dreams. Usually a device is worn while sleeping that can detect when the sleeper enters a REM phase and triggers a noise and/or flashing lights with the goal of these stimuli being incorporated into the dreamer's dream. For example flashing lights might be translated to a car's headlights in a dream.

A well known dream induction device is the Nova Dreamer which has been discontinued as of 2006. However, a newer version is being worked on, but as of now is not available [22]. A European induction device known as the Rem dreamer is still in production.

Additional techniques[edit | edit source]

- Meditation, and involvement in a conscious focusing on activities can strengthen the ability to experience lucid dreams by making the person more susceptible to noticing small discrepancies of their surroundings. [23]

- Hypnotism may help one achieve lucidity.[24] Michael Katz first referenced using simple hypnotic induction for the purpose of initiating lucid dreams in his introduction to the first edition of the book " Dream yoga and the Practice of Natural Light". He has subsequently since the early 1980's used this "guided nap" technique during dream yoga and lucid dream trainings he conducts internationally and maintains an archive of examples.[25]

Reality testing[edit | edit source]

Reality testing (or reality checking) is a common method used by people to determine whether or not they are dreaming. It involves performing an action with results that will be different if the tester is dreaming. By practicing these tests during waking life, one may eventually decide to perform such a test while dreaming, which may fail and let the dreamer realize that they are dreaming.

Common reality tests include:

- Reading some text, looking away from the text, and reading it again - in a dream, the text will probably have changed.

- Looking at one's watch (remembering the time), looking away, and looking back. As with the text, the time will probably have changed randomly and radically at the second glance or contain strange letters and characters.[26]

- Flipping a light switch. Light levels rarely change in dreams.

- Looking into a mirror; in dreams, reflections from a mirror often appear to be blurred, distorted or incorrect.[27]

- Plugging one's nose shut, and attempting to breathe through it, or attempting to breathe underwater. It is usually possible to breathe while doing this because the tester is not actually plugging their nose in real life.

- Looking at one's hands one or more times. Hands may look distorted, or grow additional fingers in a dream.

- Gripping and stretching a finger. In a dream, body image can become distorted, and pulling a finger can elongate it. Also, the number of fingers can shift when stared at.

- Jumping into the air. Gravity is often distorted in a dream state and floating or flying may occur.

- Looking around and seeing everything blurred, as if underwater.

- Being able to move through solid objects like walls.

- Putting one's finger through the palm of the other hand.

- Closing one eye and looking at one's nose. The dreamer may not see their nose as everyday details that usually go unnoticed in waking life are often absent during a dream.

Dream signs[edit | edit source]

Another form of reality testing involves identifying one's dream signs, clues that one is dreaming. Dream signs are often categorized as follows:

- Action — The dreamer, another dream character, or a thing does something unusual or impossible in waking life, such being able to fly, or noticing photographs in a magazine or newspaper becoming three-dimensional with full movement.

- Context — The place or situation in the dream is strange, and includes fictional characters or places.

- Form — The dreamer, another character, or an object changes shape, is oddly formed, or transforms. This may include the presence of unusual clothing or hair, or a third person view of the dreamer.

- Awareness — A peculiar thought, a strong emotion, an unusual sensation, or an altered perception. In some cases when moving one's head from side to side, one may notice a strange stuttering or 'strobing' of the image.

- Cohesion — Sometimes the dreamer may seem to teleport to another location in a dream, without a noticeable transition.

Prolonging lucid dreams[edit | edit source]

One problem faced by people wishing to lucid dream is awakening prematurely. This premature awakening can be especially frustrating after investing considerable time into achieving lucidity in the first place. Stephen LaBerge proposed two ways to prolong a lucid dream. The first technique involves spinning one's dream body. He proposed that when spinning, the dreamer is engaging parts of the brain that may also be involved in REM activity, helping to prolong REM. The second technique is rubbing one's hands. This technique is intended to engage the dreamer's brain in producing the sensation of rubbing hands, preventing the sensation of lying in bed from creeping into awareness. LaBerge tested his hypothesis by asking 34 volunteers to either spin, rub their hands, or do nothing. Results showed 90% of dreams were prolonged by hand rubbing and 96% prolonged by spinning. Only 33% of lucid dreams were prolonged with taking no action.[28]

Other associated phenomena[edit | edit source]

- Rapid eye movement (REM)

- During dreaming sleep the eyes move rapidly. Scientific research has found that these eye movements correspond to the direction in which the dreamer is "looking" in his/her dreamscape; this apparently enabled trained lucid dreamers to communicate the content of their dreams as they were happening to researchers by using eye movement signals.[7] This research produced various results, such as that events in dreams take place in real time rather than going by in a flash.

- False awakenings

- In a false awakening, one suddenly dreams of having been awakened. Commonly in a false awakening the room is identical to the room that the person fell asleep in, with several small subtle differences. If the person was lucid, he/she often believes that he/she is no longer dreaming, and may start exiting their room etc. Since the person is actually still dreaming, this is called a "false awakening".

This is often a nemesis in the art of lucid dreaming because it usually causes people to give up their awareness of being in a dream, but it can also cause someone to become lucid if the person does a reality check whenever he/she awakens. People who keep a dream journal and write down their dreams upon awakening sometimes report having to write down the same dream multiple times because of this phenomenon. It has also been known to cause bedwetting as one may dream that they have awoken to go to the restroom, but in reality are still dreaming.

- Sleep paralysis

- During REM sleep the body is paralyzed by a mechanism in the brain, because otherwise the movements which occur in the dream would actually cause the body to move. However, it is possible for this mechanism to be triggered before, during, or after normal sleep while the brain awakens. This can lead to a state where a person is lying in his or her bed and he or she feels frozen. Hypnagogic hallucinations may occur in this state, especially auditory ones. Experiencing sleep paralysis is a necessary part of WILD.

See also[edit | edit source]

- Dream

- The Art of Dreaming

- Dream argument

- List of dream diaries

- Pre-lucid dream

- Dream question

- Astral projection

- Hemi-Sync

Notes[edit | edit source]

- ↑

Watanabe,-Tsuneo (Mar 2003). "Lucid Dreaming: Its Experimental Proof and Psychological Conditions". Journal-of-International-Society-of-Life-Information-Science. 21 (1): 159–162. Unknown parameter

|quotes=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑

LaBerge, Stephen (1990). Bootzen, R. R., Kihlstrom, J.F. & Schacter, D.L., (Eds.), ed. Lucid Dreaming: Psychophysiological Studies of Consciousness during REM Sleep Sleep and Cognition Check

|url=value (help). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. pp. pp. 109 &ndash, 126. - ↑

LaBerge, Stephen (1995). "Validity Established of DreamLight Cues for Eliciting Lucid Dreaming". Dreaming. 5 (3). Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Muzur A, Pace-Schott EF, Allan Hobson (Nov 2002). The prefrontal cortex in sleep. Trends Cogn Sci. 1;2(11):475-481.

- ↑ Hobson, J. Allan (2001). The Dream Drugstore: Chemically Altered States of Consciousness. Cambridge,Massachusetts: MIT Press. pp. 96–98. ISBN 978-0262582209.

- ↑

Spoormaker,-Victor-I; van-den-Bout,-Jan (2006). "Lucid Dreaming Treatment for Nightmares: A Pilot Study". Psychotherapy-and-Psychosomatics. 75(6): 389–394. Unknown parameter

|quotes=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 7.0 7.1 LaBerge, S.(2000). Lucid dreaming: Evidence and methodology. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 23(6), 962-3.

- ↑ Erlacher, D. & Schredl, M. (2004). Required time for motor activities in lucid dreams. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 99, 1239-1242.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Lynne Levitan, Stephen LaBerge (1991). Other Worlds: Out-of-Body Experiences and Lucid Dreams, Nightlight 3(2-3). The Lucidity Institute.

- ↑ Green,J. Timothy (1995). "Lucid dreams as one method of replicating components of the near-death experience in a laboratory setting". Journal-of-Near-Death-Studies. 14: 49-. Unknown parameter

|quotes=ignored (help) - ↑ Letter from St. Augustine of Hippo

- ↑ (March 2005). The Best Sleep Posture for Lucid Dreaming: A Revised Experiment Testing a Method of Tibetan Dream Yoga. The Lucidity Institute.

- ↑ Dream Yoga and the Practice of Natural Light, 2nd edition, Snowlion Publications; authored by Chogyal Namkhai Norbu, an eminent Tibetan Lama, and his student Michael Katz, a Psychologist and lucid dream trainer. See [1]

- ↑ Religio Medici, part 2:11. Text available at http://penelope.uchicago.edu/relmed/relmed.html

- ↑ Frederik van Eeden (1913). A study of Dreams. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, Vol. 26.

- ↑ Blackmore, Susan (1991). "Lucid Dreaming: Awake in Your Sleep?". Skeptical Inquirer. 15: pp 362 &ndash, 370.

- ↑ G. William Domhoff (2003). Senoi Dream Theory: Myth, Scientific Method, and the Dreamwork Movement. Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ↑ LaBerge, Stephen, (1980). Lucid dreaming as a learnable skill: A case study. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 51, 1039-1042.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Stephen LaBerge (1989). How to Remember Your Dreams. Nightlight 1(1), The Lucidity Institute.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Stephen LaBerge, Leslie Phillips, Lynne Levitan (1994). An Hour of Wakefulness Before Morning Naps Makes Lucidity More Likely. NightLight 6(3). The Lucidity Institute.

- ↑ Stephen LaBerge, Lynne Levitan (1995). Validity Established of Dreamlight Cues for Eliciting Lucid Dreaming, Dreaming, Vol. 5, No. 3. The Lucidity Institute.

- ↑ Novadreamer Lucid Dream Induction Device at The Lucidity Institute

- ↑ Harry T. Hunt (1991). Lucid Dreams and Meditation. Lucidity Letter, 10(1 & 2).

- ↑ Oldis, Daniel (1974). The Lucid Dream Manifesto. pp. pages 52-53. ISBN 0-595-39539-2.

- ↑ http://www.nydzogchen.com/library/dream9.html/ KUNDROLLING, Dzogchen Community Of New York: Lucid Dreams of Community Members]

- ↑ Reality testing, Lucid Dreaming FAQ at The Lucidity Institute. (October 2006)

- ↑ Lynne Levitan, Stephen LaBerge (Summer 1993). The Light and Mirror Experiment. Nightlight 5(10). The Lucidity Institute.

- ↑ Stephen LaBerge (1995). Prolonging Lucid Dreams. NightLight 7(3-4). The Lucidity Institute.

Further reading[edit | edit source]

- LaBerge, Stephen (1985). Lucid Dreaming. ISBN 0-87477-342-3.

- LaBerge, Stephen (1991). Exploring the World of Lucid Dreaming. ISBN 0-345-37410-X.

- Gackenbach, Jayne (1988). Conscious Mind, Sleeping Brain. ISBN 0-306-42849-0. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - Green, Celia (1968). Lucid Dreams. ISBN 0-900076-00-3.

- Green, Celia (1994). Lucid Dreaming: The Paradox of Consciousness During Sleep. ISBN 0-415-11239-7. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - Garfield, Patricia L. (1974). Creative Dreaming. ISBN 0-671-21903-0.

- de Saint-Denys, Hervey (1982). Dreams and How to Guide Them. ISBN 0-7156-1584-X.

- Godwin, Malcom (1994). The Lucid Dreamer. ISBN 0-671-87248-6.

- McElroy, Mark (2007). Lucid Dreaming for Beginners: Simple Techniques for Creating Interactive Dreams. ISBN 978-0-7387-0887-4.

- Wangyal Rinpoche, Tenzin (1998). Tibetan Yogas Of Dream And Sleep. ISBN 1-55939-101-4.

External links[edit | edit source]

cs:Lucidní snění da:Lucide drømme de:Klartraum eo:Lucida sonĝo hr:Lucidni snovi it:Sogno lucido he:חלימה מודעת ka:გააზრებული სიზმარი lt:Lucidiniai sapnai nl:Lucide droom no:Bevisst drømming simple:Lucid dream sk:Vedomé snívanie cu:снъ сънъ sr:Луцидни сан fi:Selkouni sv:Klardrömmande uk:Свідомий сон

KSF

KSF