Lytic cycle

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 3 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 3 min

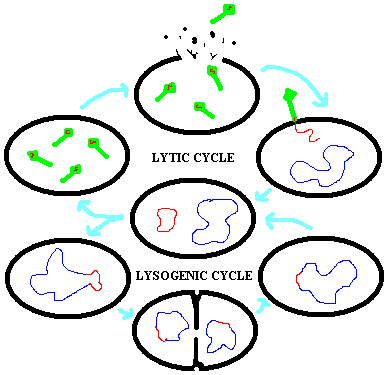

The lytic cycle is one of the two cycles of viral reproduction, the other being the lysogenic cycle. These cycles should not, however, be seen as separate, but rather as somewhat interchangeable. The lytic cycle is typically considered the main method of viral replication, since it results in the destruction of the infected cell.

|

WikiDoc Resources for Lytic cycle |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Lytic cycle Most cited articles on Lytic cycle |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Lytic cycle |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Lytic cycle at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Lytic cycle at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Lytic cycle

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Lytic cycle Discussion groups on Lytic cycle Patient Handouts on Lytic cycle Directions to Hospitals Treating Lytic cycle Risk calculators and risk factors for Lytic cycle

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Lytic cycle |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Description

[edit | edit source]The lytic cycle is a three-stage process.

Penetration

[edit | edit source]To infect a cell, a virus must first enter the cell through the plasma membrane and (if present) the cell wall. Viruses do so by either attaching to a receptor on the cell's surface or by simple mechanical force. The virus then releases its genetic material (either single- or double-stranded DNA or RNA) into the cell.

Biosynthesis

[edit | edit source]The virus' nucleic acid uses the host cell’s machinery to make large amounts of viral components. In the case of DNA viruses, the DNA transcribes itself into messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules that are then used to direct the cell's ribosomes. One of the first polypeptides to be translated is one that destroys the hosts' DNA. In retroviruses (which inject an RNA strand), a unique enzyme called reverse transcriptase transcribes the viral RNA into DNA, which is then transcribed again into mRNA.

Maturation and lysis

[edit | edit source]After many copies of viral components are made, they are assembled into complete viruses. The phage then directs production of an enzyme that breaks down the bacteria cell wall and allows fluid to enter. The cell eventually becomes filled with viruses (typically 100-200) and liquid, and bursts, or lyses; thus giving the lytic cycle its name. The new viruses are then free to infect other cells.

Lytic cycle without lysis

[edit | edit source]Some viruses escape the host cell without bursting the cell membrane, but rather bud off from it by taking a portion of the membrane with them. Because it otherwise is characteristic of the lytic cycle in other steps, it still belongs to this category. Hepatitis C viruses presumably use this method.

KSF

KSF