Neuron

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 11 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 11 min

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [5]

Neurons (also known as neurones and nerve cells) are electrically excitable cells in the nervous system that process and transmit information. In vertebrate animals, neurons are the core components of the brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves.

Overview[edit | edit source]

Neurons are usually amitotic, but some, such as the olfactory sensory neurons, undergo adult neurogenesis.[1][2][3] Neurons are typically composed of a soma, or cell body, a dendritic tree and an axon. The majority of vertebrate neurons receive input on the cell body and dendritic tree, and transmit output via the axon. However, there is great heterogeneity throughout the nervous system and the animal kingdom, in the size, shape and function of neurons.

Neurons communicate via chemical and electrical synapses, in a process known as synaptic transmission. The fundamental process that triggers synaptic transmission is the action potential, a propagating electrical signal that is generated by exploiting the electrically excitable membrane of the neuron. This is also known as a wave of depolarization.

History[edit | edit source]

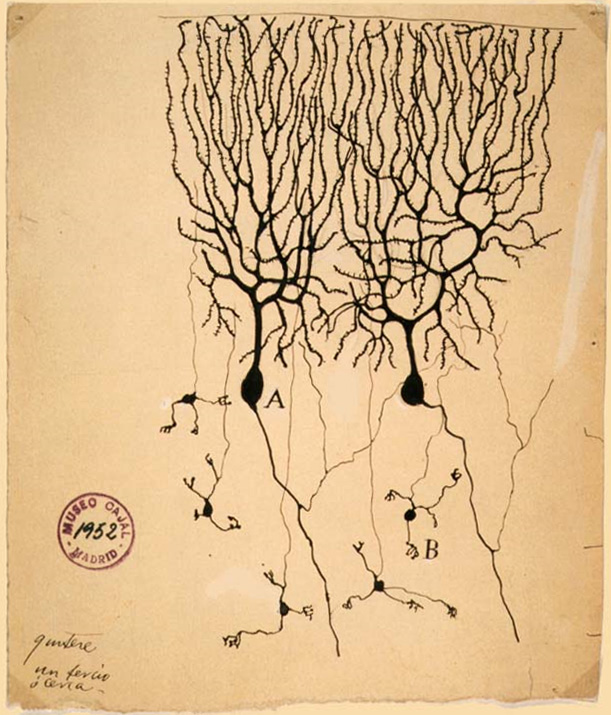

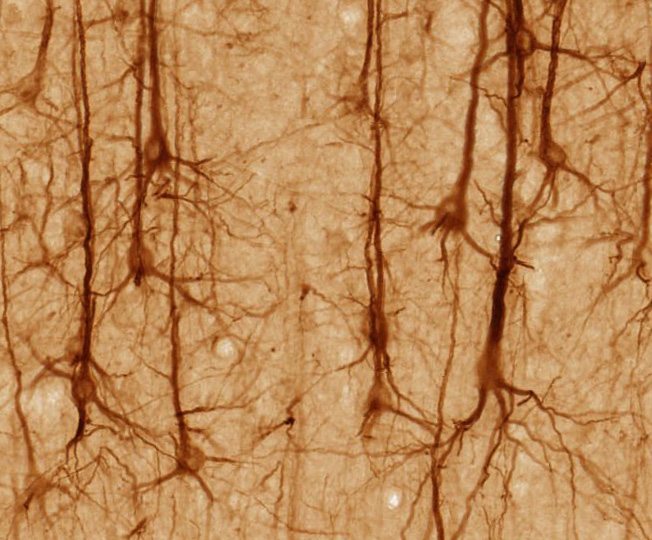

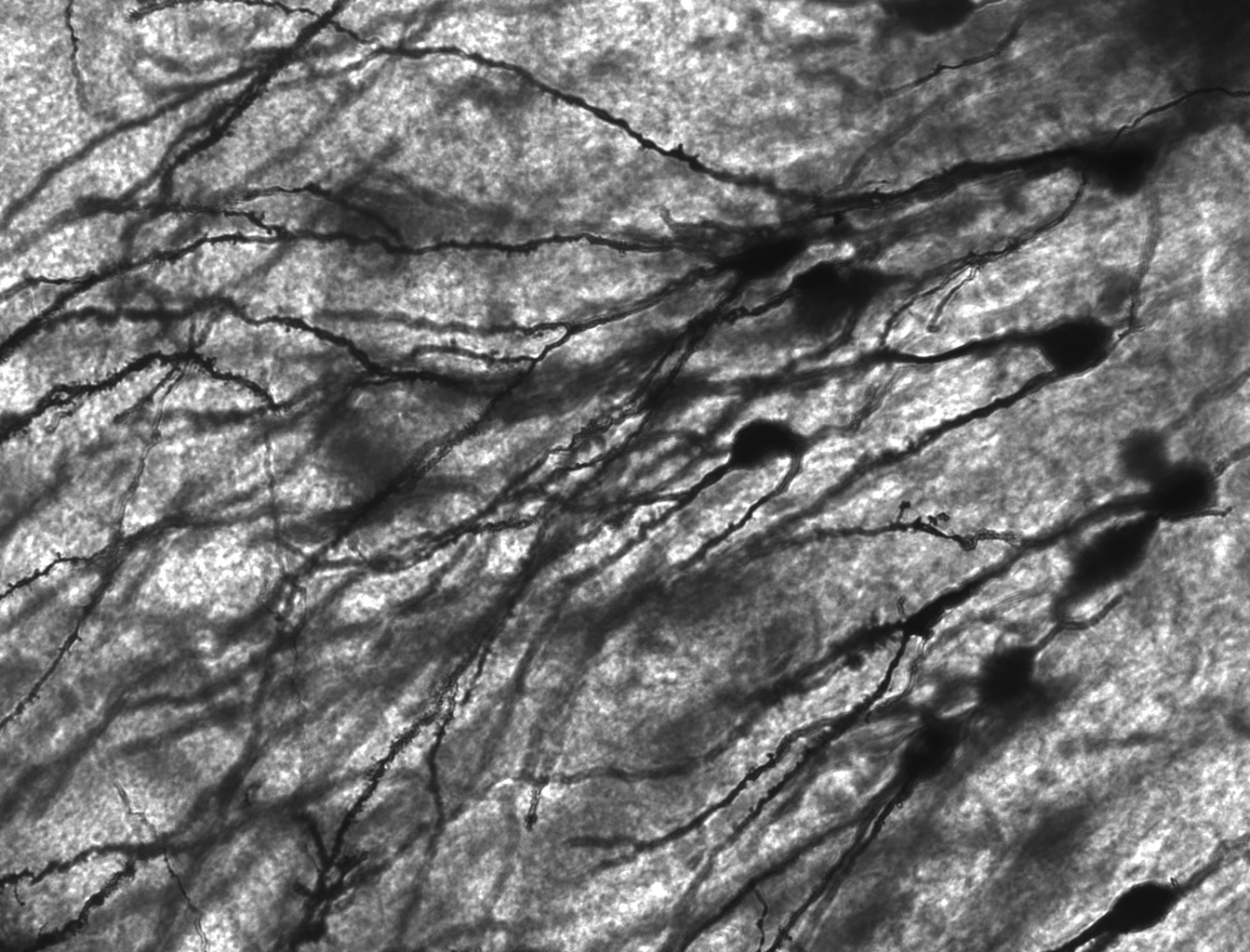

The neuron's place as the primary functional unit of the nervous system was first recognized in the early 20th century through the work of the Spanish anatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal.[4]Cajal proposed that neurons were discrete cells that communicated with each other via specialized junctions, or spaces, between cells.[4] This became known as the neuron doctrine, one of the central tenets of modern neuroscience.[4] To observe the structure of individual neurons, Cajal used a silver staining method developed by his rival, Camillo Golgi.[4] The Golgi stain is an extremely useful method for neuroanatomical investigations because, for reasons unknown, it stains a very small percentage of cells in a tissue, so one is able to see the complete microstructure of individual neurons without much overlap from other cells in the densely packed brain.[5]

Anatomy and histology[edit | edit source]

Template:Neuron map Neurons are highly specialized for the processing and transmission of cellular signals. Given the diversity of functions performed by neurons in different parts of the nervous system, there is, as expected, a wide variety in the shape, size, and electrochemical properties of neurons. For instance, the soma of a neuron can vary from 4 to 100 micrometers in diameter.[6]

- The soma is the central part of the neuron. It contains the nucleus of the cell, and therefore is where most protein synthesis occurs. The nucleus ranges from 3 to 18 micrometers in diameter.[7]

- The dendrites of a neuron are cellular extensions with many branches, and metaphorically this overall shape and structure is referred to as a dendritic tree. This is where the majority of input to the neuron occurs. Information outflow (i.e. from dendrites to other neurons) can also occur, but not across chemical synapses; there, the backflow of a nerve impulse is inhibited by the fact that an axon does not possess chemoreceptors and dendrites cannot secrete neurotransmitter chemicals. This unidirectionality of a chemical synapse explains why nerve impulses are conducted only in one direction.

- The axon is a finer, cable-like projection which can extend tens, hundreds, or even tens of thousands of times the diameter of the soma in length. The axon carries nerve signals away from the soma (and also carry some types of information back to it). Many neurons have only one axon, but this axon may - and usually will - undergo extensive branching, enabling communication with many target cells. The part of the axon where it emerges from the soma is called the 'axon hillock'. Besides being an anatomical structure, the axon hillock is also the part of the neuron that has the greatest density of voltage-dependent sodium channels. This makes it the most easily-excited part of the neuron and the spike initiation zone for the axon: in neurological terms it has the most negative hyperpolarized action potential threshold. While the axon and axon hillock are generally involved in information outflow, this region can also receive input from other neurons.

- The axon terminal is a specialized structure at the end of the axon that is used to release neurotransmitter chemicals and communicate with target neurons.

Although the canonical view of the neuron attributes dedicated functions to its various anatomical components, dendrites and axons often act in ways contrary to their so-called main function.

Axons and dendrites in the central nervous system are typically only about one micrometer thick, while some in the peripheral nervous system are much thicker. The soma is usually about 10–25 micrometers in diameter and often is not much larger than the cell nucleus it contains. The longest axon of a human motoneuron can be over a meter long, reaching from the base of the spine to the toes. Sensory neurons have axons that run from the toes to the dorsal columns, over 1.5 meters in adults. Giraffes have single axons several meters in length running along the entire length of their necks. Much of what is known about axonal function comes from studying the squid giant axon, an ideal experimental preparation because of its relatively immense size (0.5–1 millimeters thick, several centimeters long).

Classes[edit | edit source]

Structural classification[edit | edit source]

Polarity[edit | edit source]

Most neurons can be anatomically characterized as:

- Unipolar or pseudounipolar: dendrite and axon emerging from same process.

- Bipolar: single axon and single dendrite on opposite ends of the soma.

- Multipolar: more than two dendrites:

- Golgi I: neurons with long-projecting axonal processes; examples are pyramidal cells, Purkinje cells, and anterior horn cells.

- Golgi II: neurons whose axonal process projects locally; the best example are the granule cells.

Other[edit | edit source]

Furthermore, some unique neuronal types can be identified according to their location in the nervous system and distinct shape. Some examples are:

- Basket cells, neurons with dilated and knotty dendrites in the cerebellum.

- Betz cells, large motor neurons.

- Medium spiny neurons, most neurons in the corpus striatum.

- Purkinje cells, huge neurons in the cerebellum, a type of Golgi I multipolar neuron.

- pyramidal cells, neurons with triangular soma, a type of Golgi I.

- Renshaw cells, neurons with both ends linked to alpha motor neurons.

- Granule cells, a type of as Golgi II neuron.

- anterior horn cells, motoneurons located in the spinal cord.

Functional classification[edit | edit source]

Direction[edit | edit source]

- Afferent neurons convey information from tissues and organs into the central nervous system and are sometimes also called sensory neurons.

- Efferent neurons transmit signals from the central nervous system to the effector cells and are sometimes called motor neurons.

- Interneurons connect neurons within specific regions of the central nervous system.

Afferent and efferent can also refer generally to neurons which, respectively, bring information to or send information from the brain region.

Action on other neurons[edit | edit source]

- Excitatory neurons excite their target neurons. Excitatory neurons in the central nervous system, including the brain, are often glutamatergic. Neurons of the peripheral nervous system, such as spinal motoneurons that synapse onto muscle cells, often use acetylcholine as their excitatory neurotransmitter. However, this is just a general rule that is not always true. It is not the neurotransmitter that decides excitatory or inhibitory action, but rather it is the postsynaptic receptor that is responsible for the action of the neurotransmitter.

- Inhibitory neurons inhibit their target neurons. Inhibitory neurons are often interneurons. The output of some brain structures (neostriatum, globus pallidus, cerebellum) are inhibitory. The primary inhibitory neurotransmitters are GABA and glycine.

- Modulatory neurons evoke more complex effects termed neuromodulation. These neurons use such neurotransmitters as dopamine, acetylcholine, serotonin and others.

Discharge patterns[edit | edit source]

Neurons can be classified according to their electrophysiological characteristics:

- Tonic or regular spiking. Some neurons are typically constantly (or tonically) active. Example: interneurons in neurostriatum.

- Phasic or bursting. Neurons that fire in bursts are called phasic.

- Fast spiking. Some neurons are notable for their fast firing rates, for example some types of cortical inhibitory interneurons, cells in globus pallidus.

- Thin-spike. Action potentials of some neurons are more narrow compared to the others. For example, interneurons in prefrontal cortex are thin-spike neurons.

Neurotransmitter released[edit | edit source]

Some examples are cholinergic, GABAergic, glutamatergic and dopaminergic neurons.

Connectivity[edit | edit source]

Neurons communicate with one another via synapses, where the axon terminal of one cell impinges upon a dendrite or soma of another (or less commonly to an axon). Neurons such as Purkinje cells in the cerebellum can have over 1000 dendritic branches, making connections with tens of thousands of other cells; other neurons, such as the magnocellular neurons of the supraoptic nucleus, have only one or two dendrites, each of which receives thousands of synapses. Synapses can be excitatory or inhibitory and will either increase or decrease activity in the target neuron. Some neurons also communicate via electrical synapses, which are direct, electrically-conductive junctions between cells.

In a chemical synapse, the process of synaptic transmission is as follows: when an action potential reaches the axon terminal, it opens voltage-gated calcium channels, allowing calcium ions to enter the terminal. Calcium causes synaptic vesicles filled with neurotransmitter molecules to fuse with the membrane, releasing their contents into the synaptic cleft. The neurotransmitters diffuse across the synaptic cleft and activate receptors on the postsynaptic neuron.

The human brain has a huge number of synapses. Each of the 1011 (one hundred billion) neurons has on average 7,000 synaptic connections to other neurons. It has been estimated that the brain of a three-year-old child has about 1016 synapses (10 quadrillion). This number declines with age, stabilizing by adulthood. Estimates vary for an adult, ranging from 1015 to 5 x 1015 synapses (1 to 5 quadrillion).[8]

Mechanisms for propagating action potentials[edit | edit source]

The cell membrane in the axon and soma contain voltage-gated ion channels which allow the neuron to generate and propagate an electrical impulse (an action potential). Substantial early knowledge of neuron electrical activity came from experiments with squid giant axons. In 1937, John Zachary Young suggested that the giant squid axon can be used to study neuronal electrical properties.[9] As they are much larger than human neurons, but similar in nature, it was easier to study them with the technology of that time. By inserting electrodes into the giant squid axons, accurate measurements could be made of the membrane potential.

Electrical activity can be produced in neurons by a number of stimuli. Pressure, stretch, chemical transmitters, and electrical current passing across the nerve membrane as a result of a difference in voltage can all initiate nerve activity.[10]

The narrow cross-section of axons lessens the metabolic expense of carrying action potentials, but thicker axons convey impulses more rapidly. To minimize metabolic expense while maintaining rapid conduction, many neurons have insulating sheaths of myelin around their axons. The sheaths are formed by glial cells: oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system and Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system. The sheath enables action potentials to travel faster than in unmyelinated axons of the same diameter, whilst using less energy. The myelin sheath in peripheral nerves normally runs along the axon in sections about 1 mm long, punctuated by unsheathed nodes of Ranvier which contain a high density of voltage-gated ion channels. Multiple sclerosis is a neurological disorder that results from demyelination of axons in the central nervous system.

Some neurons do not generate action potentials, but instead generate a graded electrical signal, which in turn causes graded neurotransmitter release. Such nonspiking neurons tend to be sensory neurons or interneurons, because they cannot carry signals long distances.

Histology and internal structure[edit | edit source]

Nerve cell bodies stained with basophilic dyes show numerous microscopic clumps of Nissl substance (named after German psychiatrist and neuropathologist Franz Nissl, 1860–1919), which consists of rough endoplasmic reticulum and associated ribosomes. The prominence of the Nissl substance can be explained by the fact that nerve cells are metabolically very active, and hence are involved in large amounts of protein synthesis.

The cell body of a neuron is supported by a complex meshwork of structural proteins called neurofilaments, which are assembled into larger neurofibrils. Some neurons also contain pigment granules, such as neuromelanin (a brownish-black pigment, byproduct of synthesis of catecholamines) and lipofuscin (yellowish-brown pigment that accumulates with age).

There are different internal structural characteristics between axons and dendrites. Axons typically almost never contain ribosomes, except some in the initial segment. Dendrites contain granular endoplasmic reticulum or ribosomes, with diminishing amounts with distance from the cell body.

The neuron doctrine[edit | edit source]

The neuron doctrine is the now fundamental idea that neurons are the basic structural and functional units of the nervous system. The theory was put forward by Santiago Ramón y Cajal in the late 19th century. It held that neurons are discrete cells (not connected in a meshwork), acting as metabolically distinct units. Cajal further extended this to the Law of Dynamic Polarization, which states that neural transmission goes only in one direction, from dendrites toward axons[11]. As with all doctrines, there are some exceptions. For example glial cells may also play a role in information processing[12]. Also, electrical synapses are more common than previously thought,[13] meaning that there are direct-cytoplasmic connections between neurons. In fact, there are examples of neurons forming even tighter coupling; the squid giant axon arises from the fusion of multiple neurons that retain individual cell bodies and the crayfish giant axon consists of a series of neurons with high conductance septate junctions. The Law of Dynamic Polarization also has important exceptions; dendrites can serve as synaptic output sites of neurons[14] and axons can receive synaptic inputs.

Neurons in the brain[edit | edit source]

The number of neurons in the brain varies dramatically from species to species.[15] One estimate puts the human brain at about 100 billion (<math>10^{11}</math>) neurons and 100 trillion (<math>10^{14}</math>) synapses.[15] By contrast, the nematode worm (Caenorhabditis elegans) has just 302 neurons making it an ideal experimental subject as scientists have been able to map all of the organism's neurons. By contrast, Drosophila melanogaster (the fruit fly) has around 300,000 neurons (which do spike) and exhibits many complex behaviors. Many properties of neurons, from the type of neurotransmitters used to ion channel composition, are maintained across species, allowing scientists to study processes occurring in more complex organisms in much simpler experimental systems.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 López-Muñoz, F. (16 October 2006). "Neuron theory, the cornerstone of neuroscience, on the centenary of the Nobel Prize award to Santiago Ramón y Cajal". Brain Research Bulletin. 70: 391–405. doi:doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.07.010 Check

|doi=value (help). PMID 17027775. Retrieved 2007-04-02. Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Grant, Gunnar (9 January 2007 (online)). "How the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was shared between Golgi and Cajal". Brain Research Reviews. doi:doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.11.004 Check

|doi=value (help). PMID 17027775. Retrieved 2007-04-02. Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ The Neuron: Size Comparison

- ↑ Brain Facts and Figures

- ↑ Drachman D (2005). "Do we have brain to spare?". Neurology. 64 (12): 2004–5. PMID 15985565.

- ↑ Milestones in Neuroscience Research

- ↑ Electrical activity of nerves

- ↑ Sabbatini R.M.E. April-July 2003. Neurons and Synapses: The History of Its Discovery. Brain & Mind Magazine, 17. Retrieved on March 19, 2007.

- ↑ Witcher M, Kirov S, Harris K (2007). "Plasticity of perisynaptic astroglia during synaptogenesis in the mature rat hippocampus". Glia. 55 (1): 13–23. PMID 17001633.

- ↑ Connors B, Long M. "Electrical synapses in the mammalian brain". Annu Rev Neurosci. 27: 393–418. PMID 15217338.

- ↑ Djurisic M, Antic S, Chen W, Zecevic D (2004). "Voltage imaging from dendrites of mitral cells: EPSP attenuation and spike trigger zones". J Neurosci. 24 (30): 6703–14. PMID 15282273.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Williams, R and Herrup, K (2001). "The Control of Neuron Number." Originally published in The Annual Review of Neuroscience 11:423–453 (1988). Last revised Sept 28, 2001. Retrieved from http://www.nervenet.org/papers/NUMBER_REV_1988.html on May 12, 2007.

Sources[edit | edit source]

- Kandel E.R., Schwartz, J.H., Jessell, T.M. 2000. Principles of Neural Science, 4th ed., McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Bullock, T.H., Bennett, M.V.L., Johnston, D., Josephson, R., Marder, E., Fields R.D. 2005. The Neuron Doctrine, Redux, Science, V.310, p. 791-793.

- Ramón y Cajal, S. 1933 Histology, 10th ed., Wood, Baltimore.

- Roberts A., Bush B.M.H. 1981. Neurones Without Impulses. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Peters, A., Palay, S.L., Webster, H, D., 1991 The Fine Structure of the Nervous System, 3rd ed., Oxford, New York.

External links[edit | edit source]

- Cell Centered Database UC San Diego images of neurons.

- NeuronBankan online neuromics tool for cataloging neuronal types and synaptic connectivity.

- High Resolution Neuroanatomical Images of Primate and Non-Primate Brains.

ar:عصبون bg:Неврон ca:Neurona cs:Neuron da:Neuron de:Nervenzelle et:Neuron el:Νευρώνας eo:Neŭrono eu:Neurona fa:نورون ko:신경 세포 hr:Neuron io:Neurono id:Sel saraf is:Taugafruma it:Neurone he:תא עצב ka:ნეირონი la:Neuron lt:Neuronas mk:Неврон nl:Zenuwcel no:Nevron simple:Neuron sk:Neurón sr:Неурон fi:Neuroni sv:Neuron th:เซลล์ประสาท uk:Нейрон ur:عصبون yi:ניוראן

KSF

KSF