Receptor tyrosine kinase

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 8 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 8 min

Overview[edit | edit source]

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK)s are the high affinity cell surface receptors for many polypeptide growth factors, cytokines and hormones. Of the ninety unique tyrosine kinase genes idenitified in the human genome, 58 encode receptor tyrosine kinase proteins.[1] Receptor tyrosine kinases have been shown to be not only key regulators of normal cellular processes but also to have a critical role in the development and progression of many types of cancer.[2]

Receptor tyrosine kinase classes[edit | edit source]

Approximately 20 different RTK classes have been identified.[3]

- RTK class I (EGF receptor family)

- RTK class II (Insulin receptor family)

- RTK class III (PDGF receptor family)

- RTK class IV (FGF receptor family)

- RTK class V (VEGF receptor family)

- RTK class VI (HGF receptor family)

- RTK class VII (TRK receptor family)

- RTK class VIII (EPH receptor family)

- RTK class IX (AXL receptor family)

- RTK class X (LTK receptor family)

- RTK class XI (TIE receptor family)

- RTK class XII (ROR receptor family)

- RTK class XIII (DDR receptor family)

- RTK class XIV (RET receptor family)

- RTK class XV (KLG receptor family)

- RTK class XVI (RYK receptor family)

- RTK class XVII (MuSK receptor family)

Structure[edit | edit source]

Most RTKs are single subunit receptors but some e.g. the insulin receptor exist as multimeric complexes. Each monomer has a single transmembrane spanning domain composed of 25-38 amino acids, an extracellular N-terminal region and an intracellular C-terminal region. The extracellular N-terminal region is composed of a very large protein domain which binds to extracellular ligands e.g. a particular growth factor or hormone. The intracellular C-terminal region comprises domains responsible for the kinase activity of these receptors.

Kinase activity[edit | edit source]

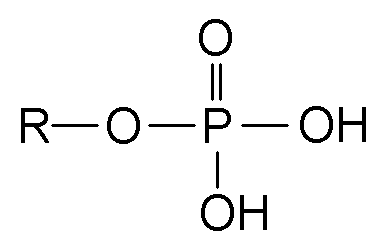

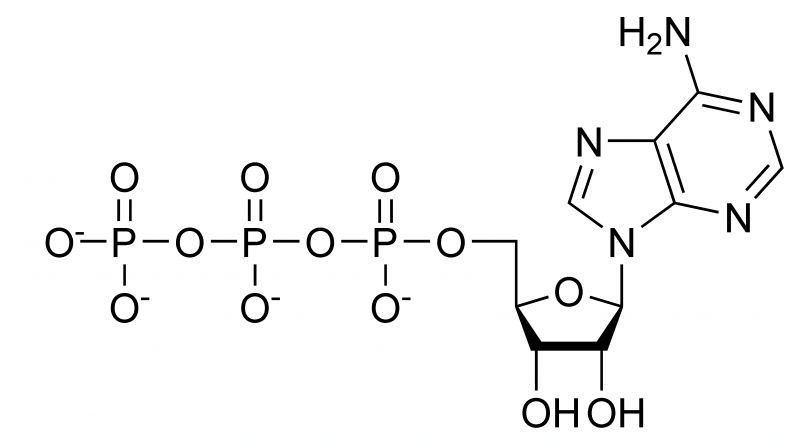

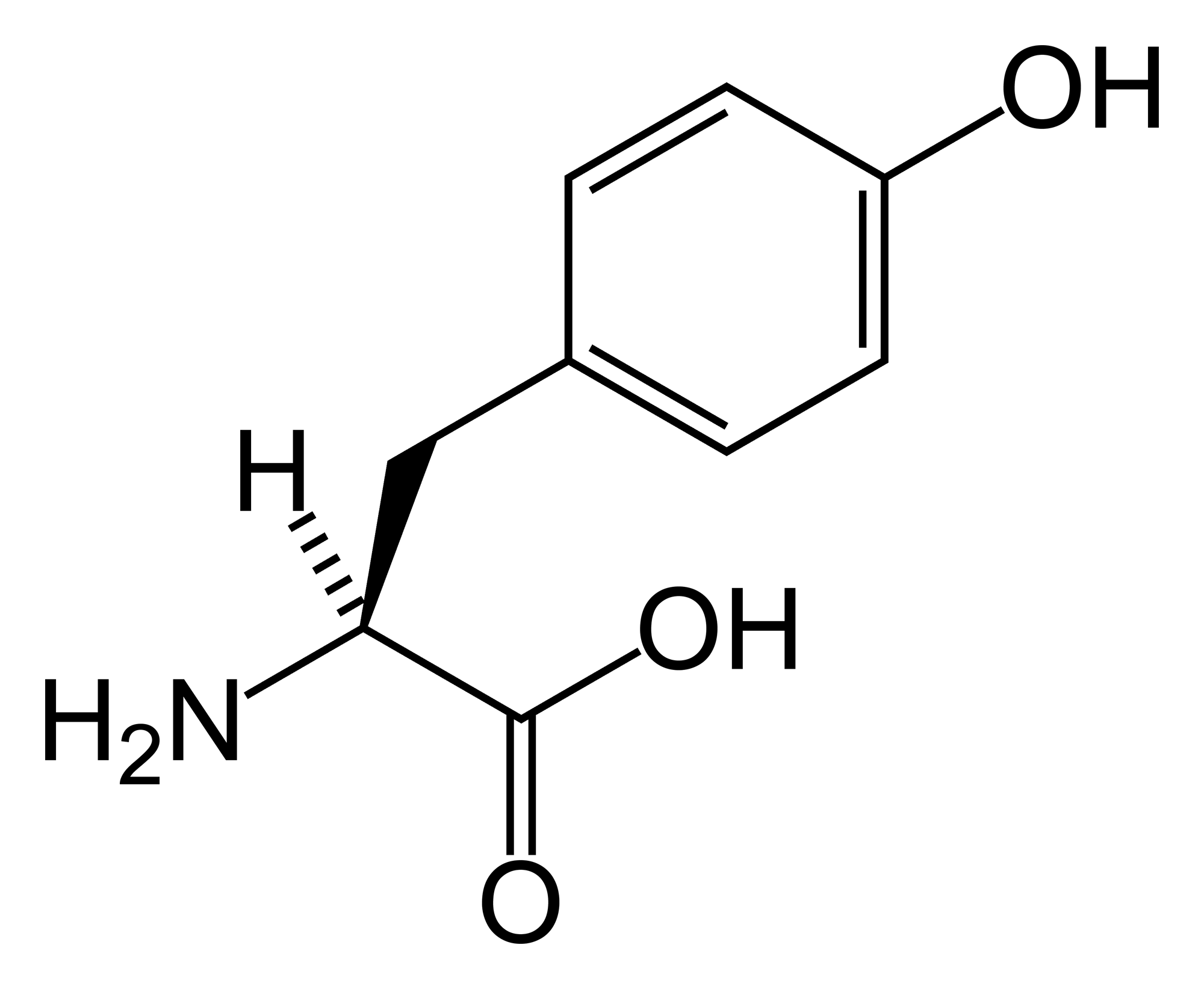

In biochemistry, a kinase is a type of enzyme that transfers phosphate groups (see below) from high-energy donor molecules, such as ATP (see below) to specific target molecules (substrates); the process is termed phosphorylation. The opposite, an enzyme that removes phosphate groups from targets, is known as a phosphatase. Kinase enzymes that specifically phosphorylate tyrosine amino acids are termed tyrosine kinases

When a growth factor binds to the extracellular domain of an RTK, its dimerization is triggered with other adjacent RTKs. Dimerization leads to a rapid activation of the proteins cytoplasmic kinase domains, the first substrate for these domains being the receptor itself. The activated receptor as a result then becomes autophosphorylated on multiple specific intracellular tyrosine residues.

Signal transduction[edit | edit source]

The phosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues within the activated receptor creates binding sites for Src homology 2 (SH2) and phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domain containing proteins.[4] Specific proteins containing these domains include Src and phospholipase Cγ, the phosphorylation and activation of these two proteins on receptor binding leading to the initiation of signal transduction pathways. Other proteins that interact with the activated receptor act as adaptor proteins and have no intrinsic enzymatic activity of their own. These adaptor proteins link RTK activation to downstream signal transduction pathways, such as the MAP kinase signalling cascade.[2]

Families[edit | edit source]

Fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) family[edit | edit source]

The fibroblast growth factors are the largest family of growth factor ligands comprising of 23 members.[5] The natural alternate splicing of four fibroblast growth factor receptor (FRFR) genes results in the production of over 48 different isoforms of FGFR.[6] These isoforms vary in their ligand binding properties and kinase domains, however all share a common extracellular region composed of three immunoglobulin (Ig) like domains (D1-D3), and thus belong to the immunoglobulin superfamily.[7] Interactions with FGFs occur via FGFR domains D2 and D3. Each receptor can be activated by several FGFs. In many cases the FGFs themselves can also activate more than one receptor, this is not the case with FGF-7 however which can only activate FGFR2b.[6] A gene for a fifth FGFR protein, FGFR5, has also been identified. In contrast to FGFRs 1-4 it lacks a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain and one isoform, FGFR5γ, only contains the extracellular domains D1 and D2.[8]

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) family[edit | edit source]

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is one of the main inducers of endothelial cell proliferation and permeability of blood vessels. Two RTKs bind to VEGF at the cell surface, VEGFR-1 (Flt-1) and VEGFR-2 (KDR/Flk-1).[9]

The VEGF receptors have an extracellular portion consisting of seven Ig-like domains so, like FGFRs, belong to the immunoglobulin superfamily. They also possess a single transmembrane spanning region and an intracellular portion containing a split tyrosine-kinase domain. VEGF-A binds to VEGFR-1 (Flt-1) and VEGFR-2 (KDR/Flk-1). VEGFR-2 appears to mediate almost all of the known cellular responses to VEGF. The function of VEGFR-1 is less well defined, although it is thought to modulate VEGFR-2 signaling. Another function of VEGFR-1 may be to act as a dummy/decoy receptor, sequestering VEGF from VEGFR-2 binding (this appears to be particularly important during vasculogenesis in the embryo). A third receptor has been discovered (VEGFR-3), however, VEGF-A is not a ligand for this receptor. VEGFR-3 mediates lymphangiogenesis in response to VEGF-C and VEGF-D.

RET receptor family[edit | edit source]

The natural alternate splicing of the RET gene results in the production of 3 different isoforms of the protein RET. RET51, RET43 and RET9 contain 51, 43 and 9 amino acids in their C-terminal tail respectively.[10] The biological roles of isoforms RET51 and RET9 are the most well studied in-vivo as these are the most common isoforms in which RET occurs.

RET is the receptor for members of the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) family of extracellular signalling molecules or ligands (GFLs).[11]

In order to activate RET GFLs first need to form a complex with a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored co-receptor. The co-receptors themselves are classified as members of the GDNF receptor-α (GFRα) protein family. Different members of the GFRα family (GFRα1-GFRα4) exhibit a specific binding activity for a specific GFLs.[12] Upon GFL-GFRα complex formation, the complex then brings together two molecules of RET, triggering trans-autophosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues within the tyrosine kinase domain of each RET molecule. Phosphorylation of these tyrosines then initiates intracellular signal transduction processes.[13]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Robinson DR, Wu YM, Lin SF. (2000). "The protein tyrosine kinase family of the human genome". Oncogene. 19 (49): 5548–5557. PMID 11114734.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Zwick, E. Bange, J. Ullrich, A. (2001). "Receptor tyrosine kinase signalling as a target for cancer intervention strategies". Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 8 (3): 161–173. PMID 11566607.

- ↑ www.genome.ad.jp [1] Retrieved on 2007-04-05

- ↑ Pawson, T. (1995). "Protein modules and signalling networks". Nature. 373 (6515): 573–580. PMID 7531822.

- ↑ Ornitz DM. and Itoh, N. (2001). "Fibroblast growth factors". Genome Biol. 2 (3): REVIEWS 3005. PMID 11276432.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Duchesne L, Tissot B.; et al. (2006). "N-glycosylation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 regulates ligand and heparan sulfate co-receptor binding". J. Biol. Chem. 281 (37): 27178–27189. PMID 16829530.

- ↑ Coutts JC, and Gallagher JT. (1995). "Receptors for fibroblast growth factors". Immunol. Cell. Biol. 73 (6): 584–589. PMID 8713482.

- ↑ Sleeman M, Fraser J.; et al. (2001). "Identification of a new fibroblast growth factor receptor, FGFR5". Gene. 271 (2): 171–182. PMID 11418238.

- ↑ Robinson, CJ and Stringer, SE. (2001). "The splice variants of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and their receptors". J. Cell. Sci. 114 (5): 853–865. PMID 11181169.

- ↑ Myers SM, Eng C.; et al. (1995). "Characterization of RET proto-oncogene 3' splicing variants and polyadenylation sites: a novel C-terminus for RET". Oncogene. 11 (10): 2039–2045. PMID 7478523.

- ↑ Baloh RH, Enomoto H.; et al. (2000). "The GDNF family ligands and receptors - implications for neural development". Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 10 (1): 103–110. PMID 10679429.

- ↑ Airaksinen MS, Titievsky A, Saarma M. (1999). "GDNF family neurotrophic factor signaling: four masters, one servant?". Mol. Cell Neurosci. 13 (5): 313–325. PMID 10356294.

- ↑ Arighi E, Borrello MG, Sariola H. (2005). "RET tyrosine kinase signaling in development and cancer". Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16 (4–5): 441–467. PMID 15982921.

See also[edit | edit source]

External links[edit | edit source]

- Tyrosine+Kinase+Receptors at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- EC 2.7.10.1

KSF

KSF