ST elevation myocardial infarction histopathology

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 5 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 5 min

|

ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction Microchapters |

|

Differentiating ST elevation myocardial infarction from other Diseases |

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

|

Case Studies |

|

ST elevation myocardial infarction histopathology On the Web |

|

ST elevation myocardial infarction histopathology in the news |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating ST elevation myocardial infarction |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for ST elevation myocardial infarction histopathology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Overview[edit | edit source]

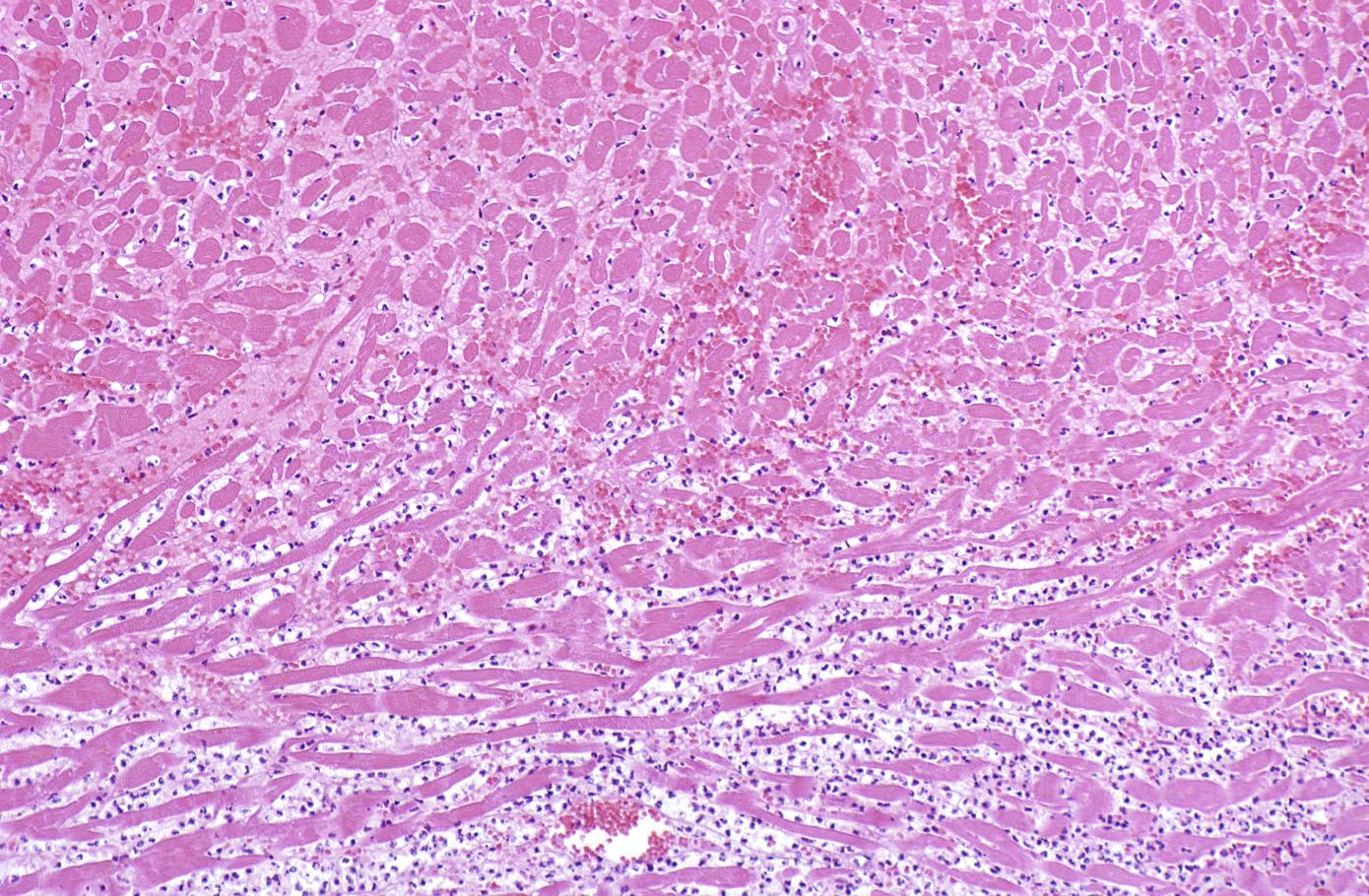

Histopathological examination of the heart may reveal infarction at autopsy. Under the microscope, myocardial infarction presents as a circumscribed area of ischemic, coagulative necrosis (cell death). On gross examination, the infarct is not identifiable within the first 12 hours.[1]

Histopathology[edit | edit source]

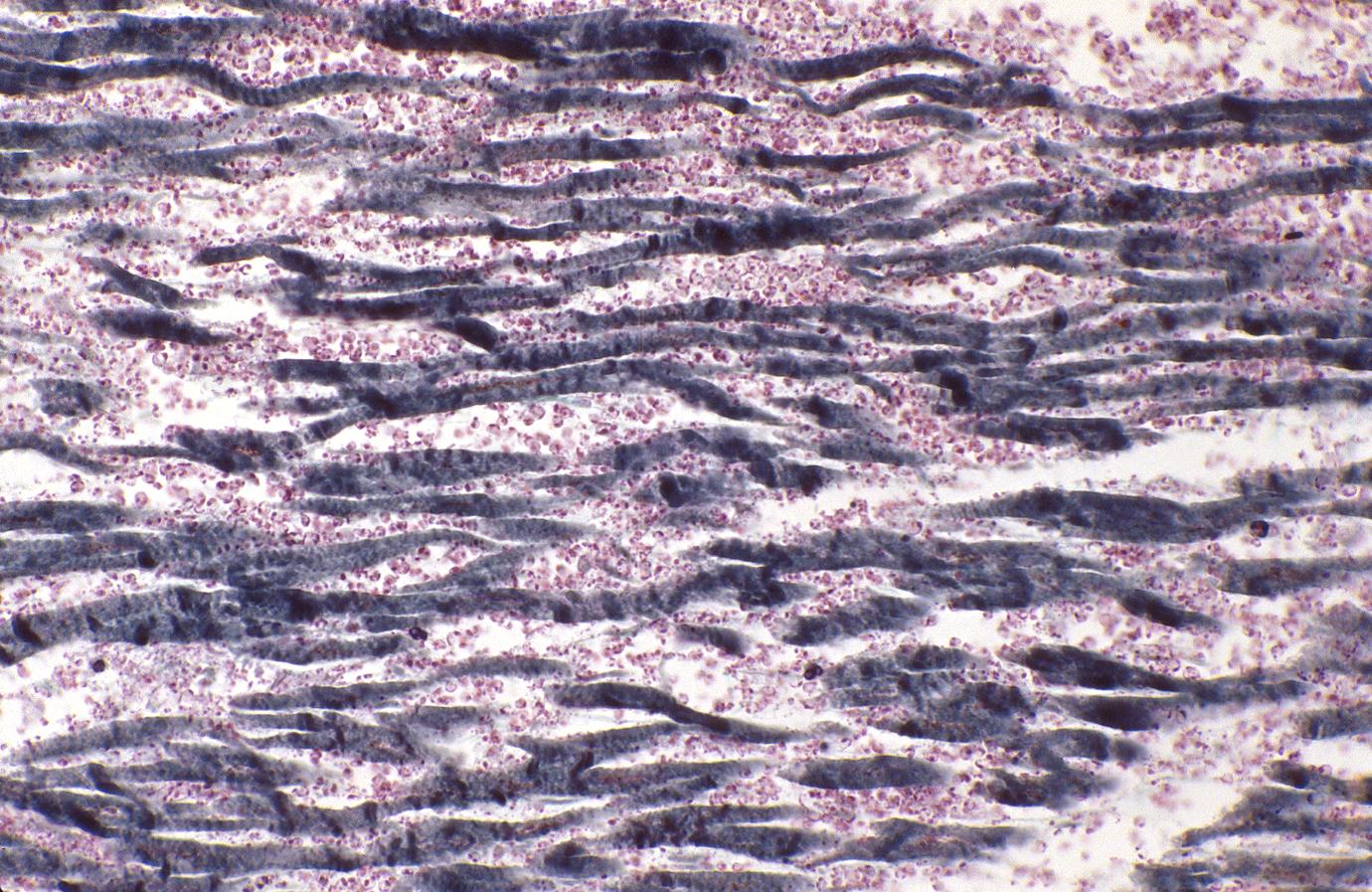

Wavy fiber phase[edit | edit source]

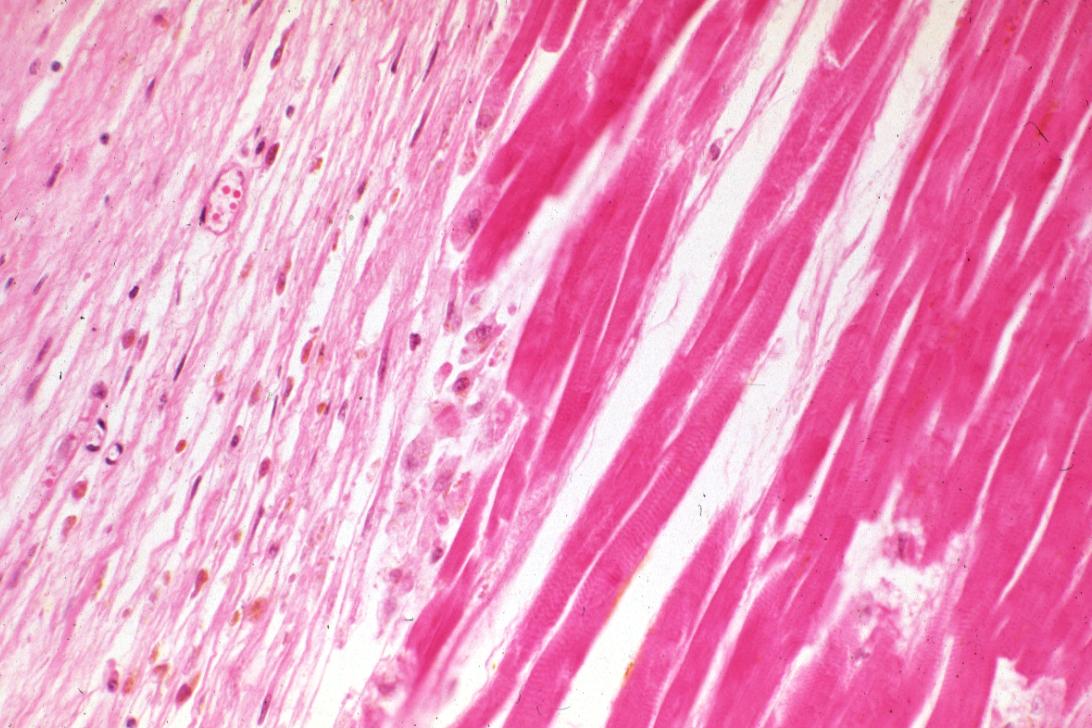

Although earlier changes can be discerned using electron microscopy, one of the earliest changes under a normal microscope are so-called wavy fibers.[2]Thin wavy myocytes are (the earliest light microscopic finding of acute myocardial infarction) visible as early as one hour following the onset of infarction. [3]

Eosinophilic phase with loss of cell nucleus[edit | edit source]

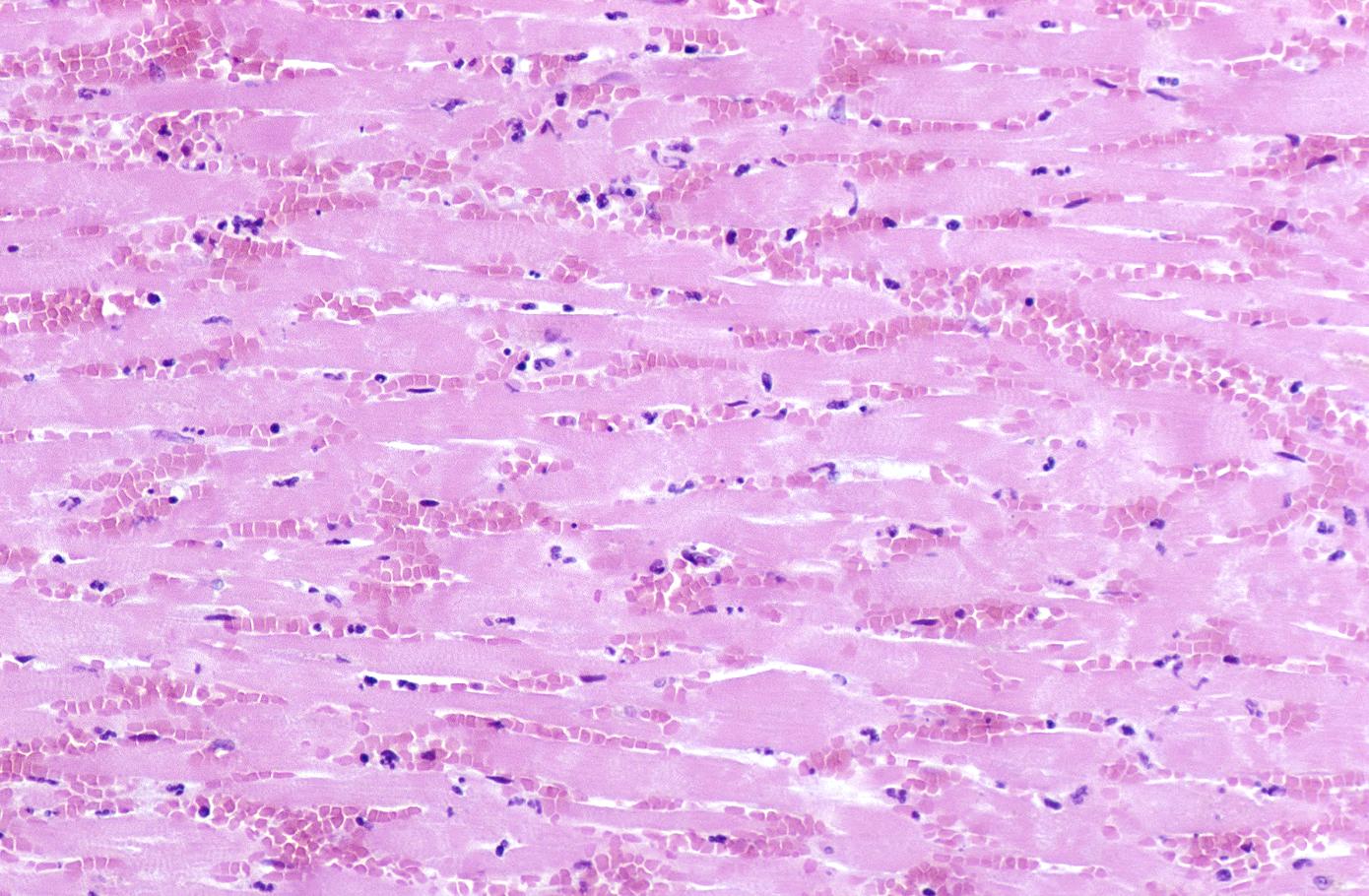

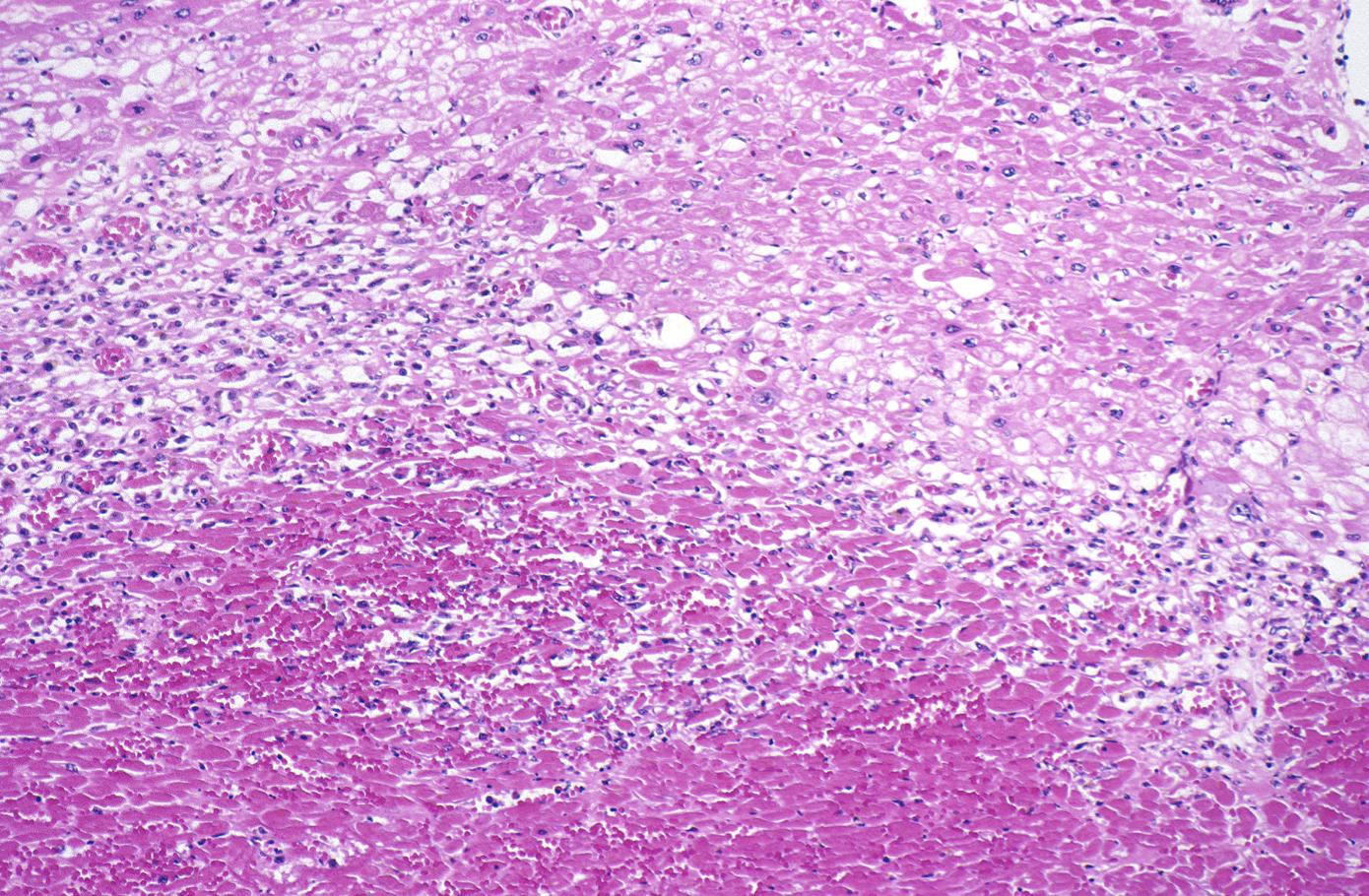

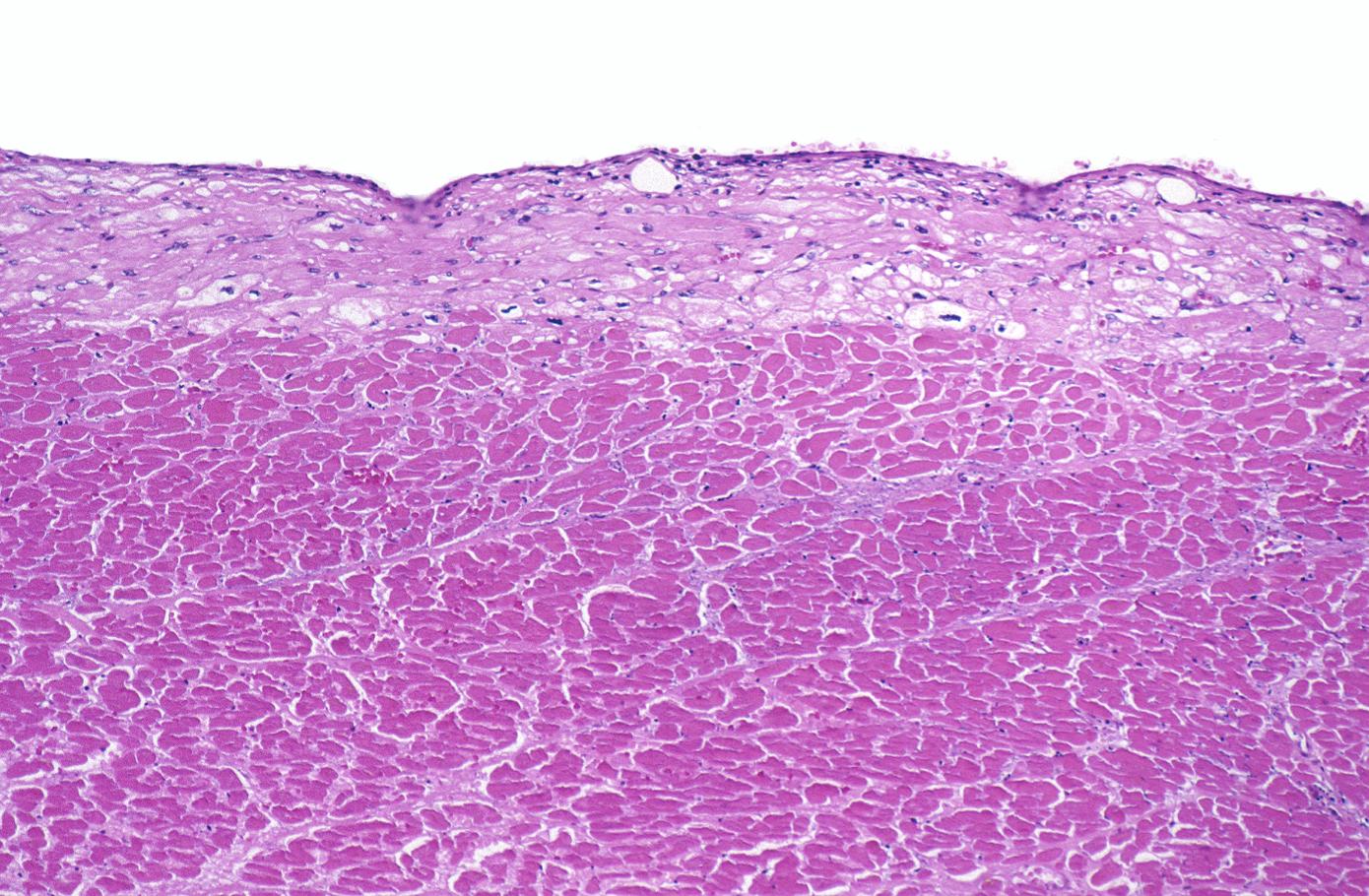

Subsequently, the myocyte cytoplasm becomes more eosinophilic (pink) and the cells lose their transversal striations, with typical changes and eventually loss of the cell nucleus.[4]

Coagulation necrosis[edit | edit source]

Coagulation necrosis, characterized by hypereosinophilia and nuclear pyknosis, followed by karyorrhexis, karyolysis, total loss of nuclei and loss of cytoplasmic cross-striations, is generally first visible in the period from 4-12 hours following infarction.[5]. Necrotic myocytes may retain their striations for a long time.[6]

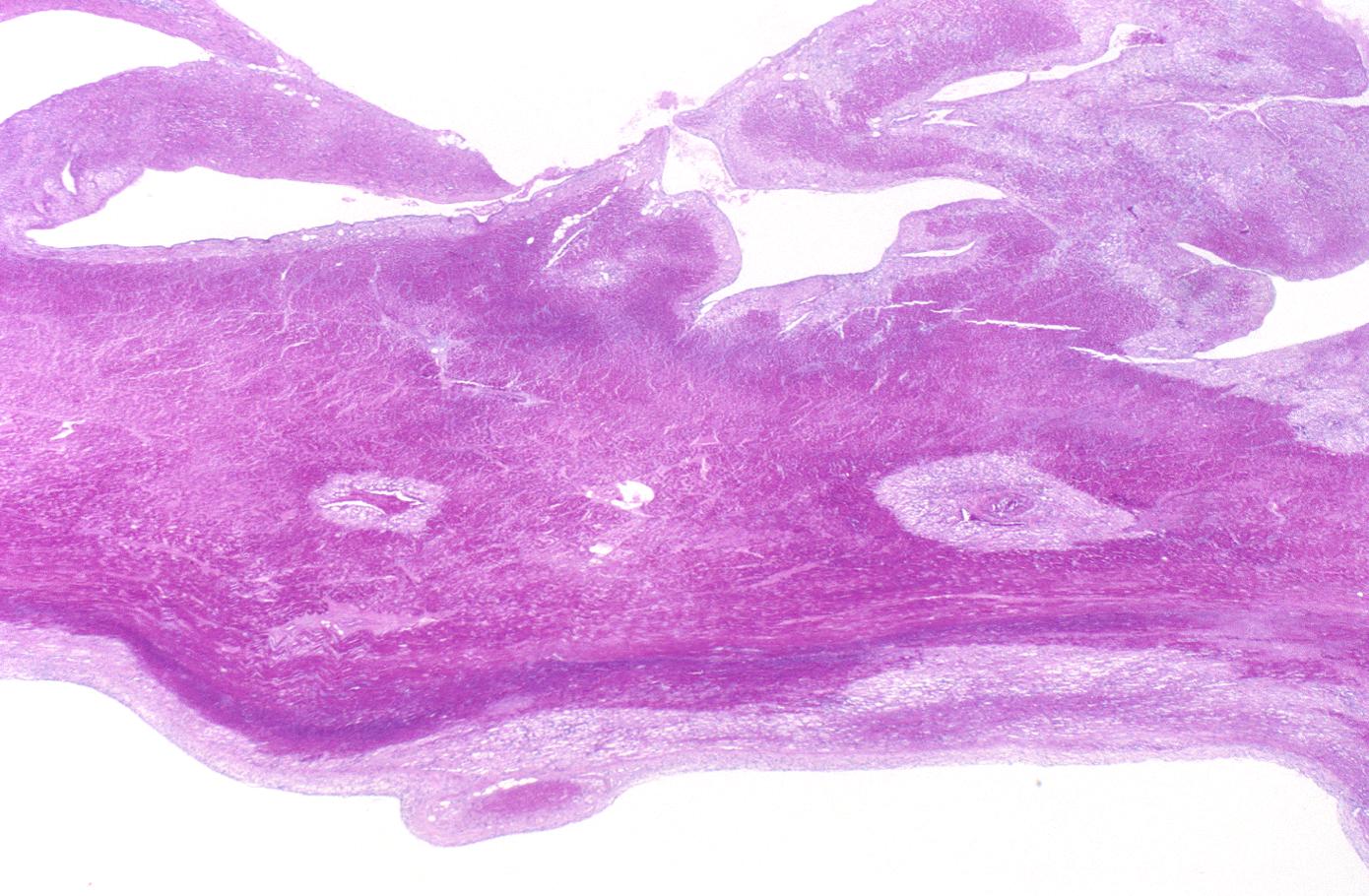

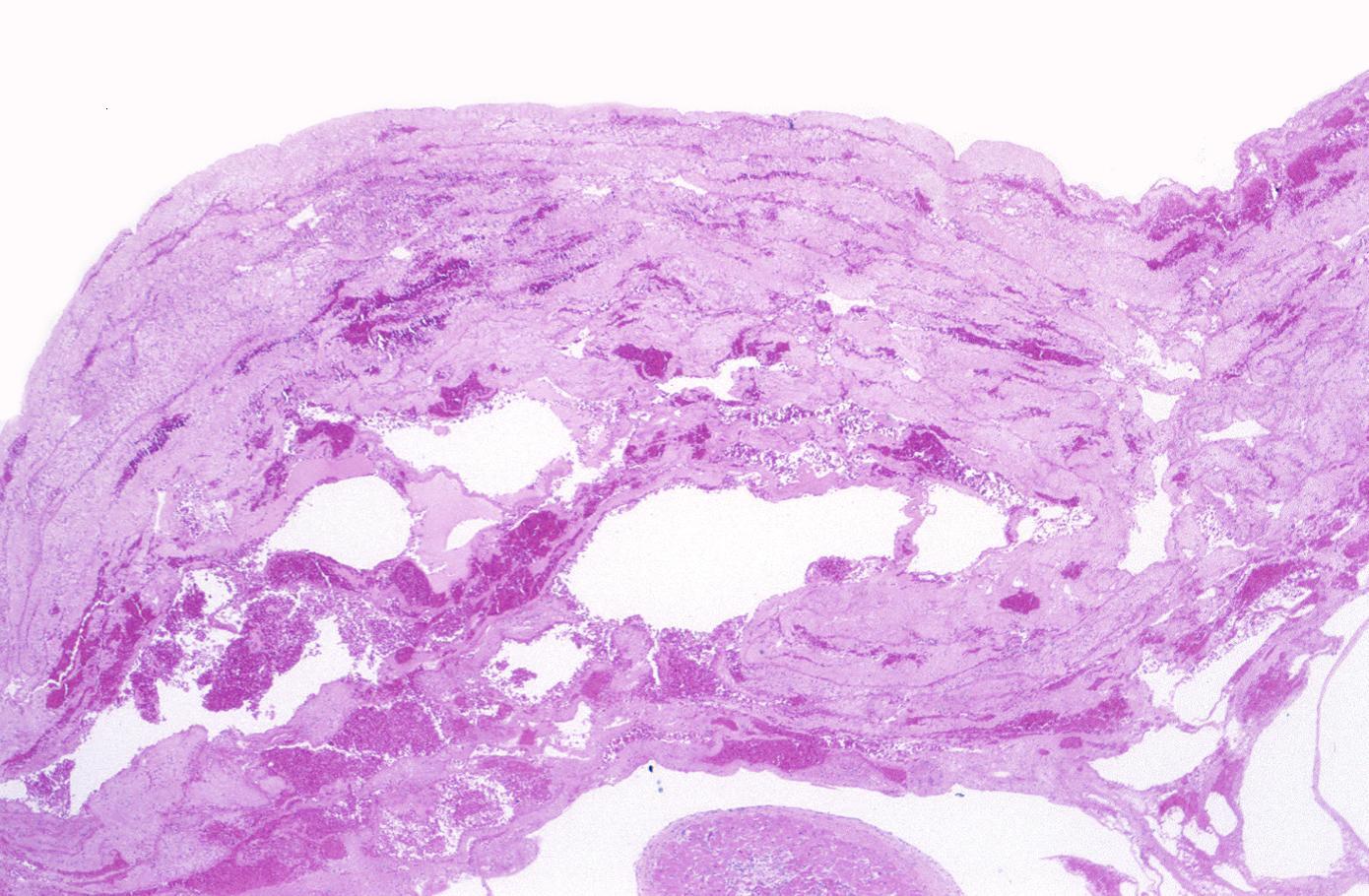

Neutrophilic infiltration (acute inflammation), edema and hemorrhage are also first visible at 4-12 hours but generally closer to 12 hours. The interstitium at the margin of the infarcted area is initially infiltrated with neutrophils, then with lymphocytes and macrophages, who phagocytose (eat) the myocyte debris. The necrotic area is surrounded and progressively invaded by granulation tissue, which will replace the infarct with a fibrous (collagenous) scar (which are typical steps in wound healing). The interstitial space (the space between cells outside of blood vessels) may be infiltrated with red blood cells.[1]

Acute inflammation is generally present in a narrow band of the periphery at 24 hours, in a broad band of the periphery at 48 hours and tends to be maximal around 72 hours, with extensive basophilic debris from degenerating neutrophils.[6]

Infiltration by macrophages, lymphocytes, eosinophils, fibroblasts and capillaries begins around the periphery at 3-10 days. Contraction band necrosis, characterized by hypereosinophilic transverse bands of precipitated myofibrils in dead myocytes is usually seen at the edge of an infarct or with reperfusion (e.g. with thrombolytic therapy).[7]

Reperfusion of an infarct is also associated with more hemorrhage, less acute inflammation, less limitation of the acute inflammation to the periphery in the first few days, reactive stromal cells, more macrophage infiltration earlier and a more patchy distribution of necrosis, especially around the periphery.[8]

These features can be recognized in cases where the perfusion was not restored; reperfused infarcts can have other hallmarks, such as contraction band necrosis.[9]

Summary of time from onset and morphologic findings:

- 1 - 3 hours: Wavy myocardial fibers

- 2 - 3 hours: Staining defect with tetrazolium or basic fuchsin dye

- 4 - 12 hours: Coagulation necrosis with loss of cross striations, contraction bands, edema, hemorrhage, and early neutrophilic infiltrate

- 18 - 24 hours: Continuing coagulation necrosis, pyknosis of nuclei, and marginal contraction bands

- 24 - 72 hours: Total loss of nuclei and striations along with heavy neutrophilic infiltrate

- 3 - 7 days: Macrophage and mononuclear infiltration begin, fibrovascular response begins

- 10 - 21 days: Fibrovascular response with prominent granulation tissue

- 7 weeks: Fibrosis

Images[edit | edit source]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Virtual Microscopic Images[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Rubin's Pathology - Clinicopathological Foundations of Medicine. Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2001. pp. p. 546. ISBN 0-7817-4733-3. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Eichbaum FW (1975). "'Wavy' myocardial fibers in spontaneous and experimental adrenergic cardiopathies". Cardiology. 60 (6): 358–65. PMID 782705.

- ↑ Bouchardy B, Majno G (1974). "Histopathology of early myocardial infarcts. A new approach". Am. J. Pathol. 74 (2): 301–30. PMC 1910768. PMID 4359735. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ S Roy. Myocardial infarction. Retrieved November 28, 2006.

- ↑ Schoen FJ. The heart. Chapter 12 in Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease, fifth edition, 1994, Cotran RS, Kumar V, Schoen FJ, eds., Philadelphia, W.B.Saunders, pp.517-582

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Fishbein MC, Maclean D, Maroko PR (1978). "The histopathologic evolution of myocardial infarction". Chest. 73 (6): 843–9. PMID 657859. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Reichenbach D, Cowan MJ. Healing of myocardial infarction with and without reperfusion. Chapter 5, in Cardiovascular Pathology, 1991, Virmani R, Atkinson JB, Fenoglio JJ, eds., Philadelphia, W.B.Saunders, pp. 86-98.

- ↑ Reichenbach D, Cowan MJ. Healing of myocardial infarction with and without reperfusion. Chapter 5, in Cardiovascular Pathology, 1991, Virmani R, Atkinson JB, Fenoglio JJ, eds., Philadelphia, W.B.Saunders, pp. 86-98.

- ↑ Fishbein MC (1990). "Reperfusion injury". Clin Cardiol. 13 (3): 213–7. PMID 2182247. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)

KSF

KSF