Schistosomiasis pathophysiology

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 6 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 6 min

|

Schistosomiasis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Schistosomiasis pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Schistosomiasis pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Schistosomiasis pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] ; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Aditya Ganti M.B.B.S. [2]

Overview[edit | edit source]

The pathogenesis of acute human schistosomiasis is mainly related to egg deposition and liberation of antigens of adult worms and eggs. A strong inflammatory response characterized by high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukins 1, 6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and circulating immune complexes participates in the pathogenesis of the acute phase of the disease. Schistosomes have a typical trematode vertebrate-invertebrate lifecycle, with humans being the definitive host. The life cycles of all five human schistosomes are broadly similar. Infection can occur by penetration of the human skin by cercaria or following the handling of contaminated soil. Cercaria gets transformed into migrating schistosomulum stage in the skin. The incubation period for acute schistosomiasis is usually 14-84 days. Both the early and late manifestations of schistosomiasis are immunologically mediated. The major pathology of infection occurs with chronic schistosomiasis in which retention of eggs in the host tissues is associated with chronic granulomatous injury.

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Life Cycle[edit | edit source]

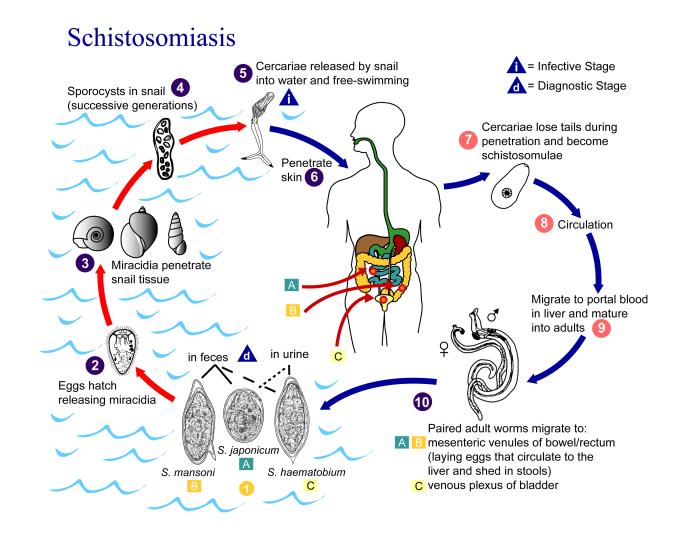

Schistosomes have a typical trematode vertebrate-invertebrate lifecycle, with humans being the definitive host. The life cycles of all five human schistosomes are broadly similar.[1][2]

Snail cycle[edit | edit source]

- Schistosomal eggs are released into the environment from infected individuals.

- The schistosomal eggs hatch on contact with fresh water to release the free-swimming miracidium.

- Miracidia infect fresh-water snails by penetrating the snail's foot.

- After infection, the miracidium transforms into a primary sporocyst.

- Germ cells within the primary sporocyst will then begin dividing to produce secondary sporocysts, which migrate to the snail's hepatopancreas.

- Once at the hepatopancreas, germ cells within the secondary sporocyst begin to divide producing thousands of new parasites, known as cercariae, which are the larvae capable of infecting mammals.

- Cercariae emerge daily from the snail host in a circadian rhythm, dependent on ambient temperature and light.

- Young cercariae are highly motile, alternating between vigorous upward movement and sinking to maintain their position in the water.

- Cercarial activity is particularly stimulated by water turbulence, by shadows and by chemicals found on human skin.

Human cycle[edit | edit source]

- Penetration of the human skin occurs after the cercaria have attached to and explored the skin.

- The parasite secretes enzymes that break down the skin's protein to enable penetration of the cercarial head through the skin.

- As the cercaria penetrates the skin it transforms into a migrating schistosomulum stage.

- The newly transformed schistosomulum may remain inside the skin for 2 days before locating a post-capillary venule.

- The schistosomulum travels from the skin to the lungs where it undergoes further developmental changes necessary for subsequent migration to the liver.

- Eight to ten days after penetration of the skin, the parasite migrates to the liver sinusoids.

- The nearly-mature worms pair, with the longer female worm residing in the gynaecophoric channel of the male.

- S. haematobium schistosomula ultimately migrates from the liver to the perivesical venous plexus of the bladder, ureters, and kidneys through the hemorrhoidal plexus.

- Parasites reach maturity in six to eight weeks, at which time they begin to produce eggs.

- S. haematobium eggs pass through the ureteral or bladder wall and into the urine.

- Only mature eggs are capable of crossing into the digestive tract, possibly through the release of proteolytic enzymes, but also as a function of host immune response, which fosters local tissue ulceration.

- Up to half the eggs released by the worm pairs become trapped in the mesenteric veins, or will be washed back into the liver, where they will become lodged.

- Trapped eggs mature normally, secreting antigens that elicit a vigorous immune response.

- The eggs themselves do not damage the body rather it is the cellular infiltration resultant from the immune response that causes the pathology classically associated with schistosomiasis.

Pathogenesis[edit | edit source]

Transmission[edit | edit source]

Infection can occur by:

- Penetration of the human skin by cercaria

- Handling of contaminated soil

- Consumption of contaminated water or food sources (e.g, unwashed garden vegetables)

Dissemination[edit | edit source]

- Cercaria gets transformed into migrating schistosomulum stage in the skin.

- Migrating schistosomulum are transported via the blood stream to respective organ system.

Incubation period[edit | edit source]

- The incubation period for acute schistosomiasis is usually 14-84 days.

Infective stages[edit | edit source]

- Cercaria are the infective stage of schistosomiasis to humans.

Diagnostic stages[edit | edit source]

- Miracidium is diagnostic for schistosomiasis.

Pathogenesis[edit | edit source]

- The pathogenesis of acute human schistosomiasis is related to egg deposition and liberation of antigens of adult worms and eggs.[3]

- A strong inflammatory response characterized by high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukins 1 and 6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, and by circulating immune complexes participates in the pathogenesis of the acute phase of the disease.

Immune response[edit | edit source]

- Both the early and late manifestations of schistosomiasis are immunologically mediated.[4][5]

- The major pathology of infection occurs with chronic schistosomiasis.

- Eggs may be trapped at sites of deposition (urinary bladder, ureters, intestine) or be carried by the bloodstream to other organs, most commonly the liver and less often the lungs and central nervous system.

- The host response to these eggs involves local as well as systemic manifestations.

- The cell-mediated immune response leads to granulomas composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and eosinophils that surround the trapped eggs and add significantly to the degree of tissue destruction.

- Granuloma formation in the bladder wall and at the ureterovesical junction results in the major disease manifestations of schistosomiasis haematobia (hematuria, dysuria, and obstructive uropathy).

- Intestinal, as well as hepatic granulomas, underlie the pathologic sequelae of the other schistosome infections( ulcerations and fibrosis of intestinal wall, hepatosplenomegaly, and portal hypertension) due to pre-sinusoidal obstruction of blood flow.

- Anti-schistosome inflammation increases circulating levels of proinflammatory cytokines.

- These responses are associated with hepcidin-mediated inhibition of iron uptake and use, leading to anemia of chronic inflammation.

- Schistosomiasis-related undernutrition may be the result of similar pathways of chronic inflammation.

- Acquired partial protective immunity against schistosomiasis has been demonstrated in some animal species and may occur in humans.

Associated conditions[edit | edit source]

- Recurrent Salmonella infections can occur in patients with schistosomiasis. Salmonella bacteria live in symbiosis within the parasite's integument, allowing them to evade eradication by many antibiotics.[6]

- Chloramphenicol-sensitive Salmonella entericaserovar Typhi has been shown to be refractory to chloramphenicol therapy in patients coinfected with Schistosoma.

- Patients coinfected with hepatitis C virus and Schistosoma have increased progression of liver fibrosis compared to patients with hepatitis C alone.[7]

- Urogenital schistosomiasis is a co-factor in the spread and progression of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and other sexually transmitted infections, especially in women, and also is associated with female infertility.[8]

Microscopic Findings[edit | edit source]

- Adult worms are about 10 mm long

{{#ev:youtube|X0eQxiwecIA}} {{#ev:youtube|9VpqxnPRvL8}}

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ "Schistosomes and Other Trematodes - Medical Microbiology - NCBI Bookshelf".

- ↑ "CDC - DPDx - Schistosomiasis Infection".

- ↑ Capron A, Dessaint JP (1992). "Immunologic aspects of schistosomiasis". Annu. Rev. Med. 43: 209–18. doi:10.1146/annurev.me.43.020192.001233. PMID 1580585.

- ↑ Colley DG, Secor WE (2014). "Immunology of human schistosomiasis". Parasite Immunol. 36 (8): 347–57. doi:10.1111/pim.12087. PMC 4278558. PMID 25142505.

- ↑ Barsoum RS, Esmat G, El-Baz T (2013). "Human schistosomiasis: clinical perspective: review". J Adv Res. 4 (5): 433–44. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2013.01.005. PMC 4293888. PMID 25685450.

- ↑ Barnhill AE, Novozhilova E, Day TA, Carlson SA (2011). "Schistosoma-associated Salmonella resist antibiotics via specific fimbrial attachments to the flatworm". Parasit Vectors. 4: 123. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-4-123. PMC 3143092. PMID 21711539.

- ↑ el-Kady IM, el-Masry SA, Badra G, Halafawy KA (2004). "Different cytokine patterns in patients coinfected with hepatitis C virus and Schistosoma mansoni". Egypt J Immunol. 11 (1): 23–9. PMID 15724383.

- ↑ "www.who.int" (PDF).

KSF

KSF