Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 20 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 20 min

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [7]

Overview[edit | edit source]

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a class of antidepressants used in the treatment of depression, anxiety disorders, and some personality disorders. They are also typically effective and used in treating premature ejaculation problems.

SSRIs increase the extracellular level of the neurotransmitter serotonin by inhibiting its reuptake into the presynaptic cell, increasing the level of serotonin available to bind to the postsynaptic receptor. They have varying degrees of selectivity for the other monoamine transporters, having little binding affinity for the noradrenaline and dopamine transporters.

The first class of psychotropic drugs to be rationally designed, SSRIs are the most widely prescribed antidepressants in many countries.[1]

List of SSRIs[edit | edit source]

Drugs in this class include:

(Trade names in parentheses)

- citalopram (Celexa, Cipramil, Emocal, Sepram, Seropram)

- escitalopram oxalate (Lexapro, Cipralex, Esertia)

- fluoxetine (Prozac, Fontex, Seromex, Seronil, Sarafem, Fluctin (EUR))

- fluvoxamine maleate (Luvox, Faverin)

- paroxetine (Paxil, Seroxat, Aropax, Deroxat, Rexetin, Xetanor, Paroxat)

- sertraline (Zoloft, Lustral, Serlain)

- dapoxetine (no known trade name)

Related antidepressants[edit | edit source]

SSRIs form a subclass of Serotonin uptake inhibitors, which includes other non-selective inhibitors as well. Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, Serotonin-noradrenaline-dopamine reuptake inhibitors and Selective serotonin reuptake enhancers are also serotonergic antidepressants.

Medical indications[edit | edit source]

The main indication for SSRIs is clinical depression. Apart from this, SSRIs are frequently prescribed for anxiety disorders like social anxiety, panic disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), eating disorders, and chronic pain. Though not specifically indicated by the manufacturers, they are also sometimes prescribed to treat irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and Lichen Simplex Chronicum. Additionally, SSRIs have been found to be effective in treating both Pathological Laughter and Crying (PLC) and premature ejaculation in up to 60% of men. All SSRIs are approved in conjunction with psychiatric disorders as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV).

Different SSRIs have different approval uses in different countries dependent on the overseeing medical branch of government in charge of regulating drugs. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) makes these approvals after trials have been submitted by pharmaceutical companies. In Europe a single body, The European Medicines Agency approves medicines for human consumption throughout the EU.

Contraindications / drug interaction[edit | edit source]

SSRIs are contraindicated with concomitant use of MAOIs (monoamine oxidase inhibitors). This can lead to increased serotonin levels which could cause a serotonin syndrome. People taking SSRIs should also avoid taking pimozide (a diphenylbutylpiperidine derivative). The atypical opioid analgesic tramadol hydrochloride (or Ultram, Ultracet) can, in rare cases, produce seizures when taken in conjunction with an SSRI or tricyclic antidepressant. Hepatic impairment is another contraindication for medications of this type.

Mode of action[edit | edit source]

Basic understanding[edit | edit source]

In the brain, messages are passed between two nerve cells via a synapse, a small gap between the cells. The cell that sends the information releases neurotransmitters (of which serotonin is one) into that gap. The neurotransmitters are then recognized by receptors on the surface of the recipient (postsynaptic) cell, which upon this stimulation, in turn, relays the signal. About 10% of the neurotransmitters are lost in this process, the other 90% are released from the receptors and taken up again by monoamine transporters into the sending (presynaptic) cell (a process called reuptake).

Some theories link depression to a lack of stimulation of the recipient neuron at a synapse. To stimulate the recipient cell, SSRIs inhibit the reuptake of serotonin. As a result, the serotonin stays in the synaptic gap longer than it normally would, and may be recognized again (and again) by the receptors of the recipient cell, stimulating it.

Pharmacodynamics[edit | edit source]

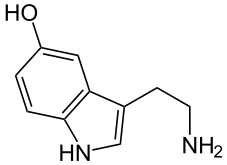

SSRIs inhibit the reuptake of the neurotransmitter serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT) into the presynaptic cell, increasing levels of 5-HT within the synaptic cleft.

But there is one counteracting effect: high serotonin levels will not only activate the postsynaptic receptors, but also flood presynaptic autoreceptors, that serve as a feedback sensor for the cell. Activation of the autoreceptors (by agonists like serotonin) triggers a throttling of serotonin production. The resulting serotonin deficiency persists for some time, as the transporter inhibition occurs downstream to the cause of the deficiency, and is therefore not able to counterbalance it. The body adapts gradually to this situation by lowering (downregulating) the sensitivity of the autoreceptors.

Of greater importance is another adaptive process: the downregulation of postsynaptic serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.

These (slowly proceeding) neurophysiological adaptions of the brain tissue are the reason why usually several weeks of continuous SSRI use are necessary for the antidepressant effect to become fully manifested, and why increased anxiety is a common side effect in the first few days or weeks of use.

Pharmacogenetics[edit | edit source]

Large bodies of research are devoted to using genetic markers to predict whether patients will respond to SSRI's or have side effects which will cause their discontinuation, although these tests are not yet ready for widespread clinical use.[2] In a double blind randomized controlled clinical trial, single nucleotide polymorphisms of the 5-HT(2A) gene were found to correlate with increased paroxetine discontinuation, but not mirtazapine (a non-SSRI antidepressant) discontinuation[3]

Interaction with carbohydrate metabolism[edit | edit source]

Serotonin is also involved in regulation of carbohydrate metabolism. Few analyses of the role of SSRIs in treating depression cover the effects on carbohydrate metabolism from intervening in serotonin handling by the body.

Neuroprotection[edit | edit source]

Studies have suggested that SSRIs may promote the growth of new neural pathways or neurogenesis[4] Also, SSRIs may protect against neurotoxicity caused by other compounds (for instance MDMA and Fenfluramine) as well as from depression itself.

Anti-inflammatory and Immunomodulation[edit | edit source]

Recent studies show pro-inflammatory cytokine processes take place during depression, mania and bipolar disease, in addition to somatic disease (such as autoimmune hypersensitivity) and is possible that symptoms manifest in these psychiatric illnesses are being attenuated by pharmacological affect of antidepressants on the immune system.[5][6][7][8][9]

SSRI's have been shown to be immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory against pro-inflammatory cytokine processes, specifically on the regulation of Interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) and Interleukin-10 (IL-10), as well as TNF-alpha and Interleukin-6 (IL-6). Antidepressants have also been shown to suppress TH1 upregulation.[10][11][12][13]

Future serotonergic antidepressants may be made to specifically target the immune system by either blocking the actions of pro-inflammatory cytokines or increasing the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines.[14]

SSRIs versus TCAs[edit | edit source]

SSRIs are described as 'selective' because they affect only the reuptake pumps responsible for serotonin, as opposed to earlier antidepressants, which affect other monoamine neurotransmitters as well. Because of this, SSRIs lack some of the side effects of the more general drugs.

There appears to be no significant difference in effectiveness between SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants, which were the most commonly used class of antidepressants before the development of SSRIs.[15] However, SSRIs have the important advantage that their toxic dose is high, and, therefore, they are much more difficult to use as a means to commit suicide. Further, they have fewer and milder side effects. Tricyclic antidepressant also have a higher risk of serious cardiovascular side effects which SSRIs lack.

SSRIs versus 5-HT-Prodrugs[edit | edit source]

Serotonin cannot be administered directly because when ingested orally, it will not cross the blood-brain barrier, and therefore would have no effect on brain functions. Also, serotonin would activate every synapse it reaches, whereas SSRIs only enhance a signal that is already present, but too weak to come through.

Biosynthetically serotonin is made from tryptophan, an amino acid. If depression is caused by lack of serotonin, rather than insensitivity to it, SSRIs alone will not work well, whereas supplementing with tryptophan will. In 1989, the Food and Drug Administration made tryptophan available by prescription only, in response to an outbreak of eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome caused by impure L-tryptophan supplements sold over-the-counter. With current standards, L-tryptophan is again available over the counter in the US as well as supplement 5-HTP which is a direct precursor to serotonin.

Adverse effects[edit | edit source]

General side effects[edit | edit source]

General side effects are mostly present during the first 1-4 weeks while the body adapts to the drug (with the exception of sexual side effects, which tend to occur later in treatment). In fact, it often takes 6-8 weeks for the drug to begin reaching its full potential (the slow onset is considered a downside to treatment with SSRIs). Almost all SSRIs are known to cause one or more of these symptoms:

- nausea

- drowsiness or somnolence

- headache

- clenching of teeth

- extremely vivid and strange dreams

- dizziness

- changes in appetite

- weight loss/gain (measured by a change in bodyweight of 7 pounds)

- may result in a double risk of bone fractures and injuries

- changes in sexual behaviour (see the next section)

- increased feelings of depression and anxiety (which may sometimes provoke panic attacks)

- tremors

- autonomic dysfunction including orthostatic hypotension, increased or reduced sweating

- akathisia

- liver or renal impairment

- thoughts of suicide

Common gastrointestinal side effects include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, which are brought about by the actions of serotonin on the gastrointestinal tract.

Most side effects usually disappear after the adaptation phase, when the antidepressive effects begin to show. However, despite being called general, the side effects and their durations are highly individual and drug-specific. Usually the treatment is begun with a small dose to see how the patient's body reacts to the drug, after that either the dose can be adjusted (eg. Prozac in the UK is begun at a 20mg dose, and then adjusted as necessary to 40mg or 60mg). Should the drug prove not to be effective, or the side effects intolerable to he patient, another common route is to switch treatment to either another SSRI, or an SNRI. A landmark study in the use of anti-depressants and their role in step-therapy can be found in the STAR*D trial.

Mania or hypomania is a possible side-effect. Users with some type of bipolar disorder are at a much higher risk, however SSRI-induced mania in patients previously diagnosed with unipolar depression can trigger a bipolar diagnosis.

Sexual side effects[edit | edit source]

SSRIs can cause various types of sexual dysfunction such as anorgasmia, erectile dysfunction, and diminished libido. Initial studies found that such side effects occur in less than 10% of patients, but since these studies relied on unprompted reporting, the frequency was probably underestimated. In more recent studies, doctors have specifically asked about sexual difficulties, and found that they are present in between 17% [16] and 41% [17] of patients. This dysfunction occasionally disappears spontaneously without stopping the SSRI, and in most cases resolves after discontinuance. In some cases, however, it does not; this is known as PSSD.

It is believed that sexual dysfunction is caused by an SSRI induced reduction in dopamine. Stimulation of postsynaptic 5-ht2 and 5-ht3 receptors decreases dopamine release from the Substantia Nigra. Sexual dysfunction caused by SSRIs can sometimes be mitigated by several different drugs. These include bupropion, buspirone, methylphenidate, mirtazapine, amphetamine, pramipexole and ropinirole.

SSRIs have been proposed as a drug to treat premature ejaculation.[18]

Cardiovascular side effects[edit | edit source]

SSRIs inhibit cardiac and vascular sodium, calcium and potassium channels and prolong QT intervals.[19] Cardiovascular events associated with SSRI use include cardiac arrhythmias, orthostatic hypotension, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter and supraventricular tachycardia. In overdose, fluoxetine has been reported to cause sinus tachycardia, myocardial Infarction, junctional rhythms and trigeminy. While the total incidence of adverse cardiac effects has been indicated to be less than 0.0003 percent,[20] Clinicians are advised to be vigilant about potential adverse reactions and ECG control may be suggested during therapy, especially in patients with cardiovascular disorders.[21]

Vascular resistance is modulated in a complex fashion by serotonin receptors. In healthy people, serotonin causes vasodilation. For example, in the cerebral arteries, the 5-HT1 receptor causes vasoconstriction, which is why sumatriptan succinate (a 5-HT1 agonist) can be used in the treatment of migraine headaches. Serotonin also plays an important role in angina. While serotonin has a vasodilatory effect on normal coronary arteries (an effect that is blocked by the 5-HT2 receptor antagonist ketanserin), serotonin produces direct unopposed vasoconstriction in damaged endothelium. In patients with damaged endothelium (such as those with significant coronary artery disease), it has been speculated that there may be an increase in myocardial ischemia secondary to an increase in vasoconstrictive serotonin in the environment caused by treatment with SSRIs.[22]

Discontinuation syndrome[edit | edit source]

SSRIs are not addictive in the conventional medical use of the word (i.e. animals given free access to the drug do not actively seek it out and do not seek to increase the dose), but suddenly discontinuing their use is known to produce both somatic and psychological withdrawal symptoms. Notably patients describe having "Brain Zaps" or "Fever Jolts". Discontinuation symptoms can last from weeks to months and can be distressing for the patient.

SSRIs and Pregnancy[edit | edit source]

The FDA issued a warning on July 19, 2006 stating nursing mothers on SSRIs must discuss treatment with their physicians.

When taken by pregnant women, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) cross the placenta and have the potential to affect newborns. Although SSRIs have not been associated with congenital malformations, some evidence suggests that they are associated with neonatal complications such as neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) and persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPH).

A study suggests there may be additional, though rare, risks of SSRI medications during pregnancy. This study focused on newborn babies with persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPHN), which is a serious and life-threatening lung condition that occurs soon after birth of the newborn. Babies with PPHN have high pressure in their lung blood vessels and are not able to get enough oxygen into their bloodstream. About 1 to 2 babies per 1000 babies born in the U.S. develop PPHN shortly after birth, and often they need intensive medical care. In this study PPHN was six times more common in babies whose mothers took an SSRI antidepressant after the 20th week of the pregnancy compared to babies whose mothers did not take an antidepressant.[23]

SSRI withdrawal syndromes also have been documented in neonates. Investigators found that by November 2003, a total of 93 cases of SSRI use associated with either neonatal convulsions or withdrawal syndrome had been reported. Subsequently, the authors of a Lancet study concluded that doctors should avoid or cautiously manage the prescribing of these drugs to pregnant women with psychiatric disorders.[24]

In 2006, a widely reported study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) challenged the common assumption that hormonal changes during pregnancy protected expectant mothers against depression, finding that discontinuing anti-depressive medication during pregnancy led to more frequent relapse.[25] The JAMA article did not disclose that several authors had financial ties to pharmaceutical companies making antidepressants. The JAMA later published a correction noting the ties[26] and the authors maintain that the ties have no bearing on their research work. Obstetrician and perinatologist Adam Urato told the Wall Street Journal that patients and medical professionals need advice free of industry influence.[27]

Suicidality and Aggression[edit | edit source]

Over the years there have been many accusations by patients and their families of SSRIs causing suicidal ideation and aggressive (or homicidal) behavior. The scientific evidence supporting this claim has been criticized by drug advocates, but alternative medicine sites often claim that patients committed suicide or engaged in aggressive and / or criminal acts using SSRIs.[28] Manufacturers of SSRIs historically have vehemently denied any such link and have always blamed the disease rather than the treatment. However, evidence from case studies, epidemiological studies, experimental research, and theory supports the view that SSRIs increase suicide risk for some patients.[29]

In the United States there is a required box warning for suicide risk in children. In the UK, all "antidepressant" medications except Prozac have been banned for people under 18. In late 2004 the first U.S. black box warning was added which applied only to children 12 and under. Recently experts recommended expanding the warning to adults. In general the risk of suicide is twice as great when taking an SSRI regardless of the type of diagnosis or whether the patient was considered a healthy volunteer for trial purposes.

On Dec 13, 2006, a U.S. Food and Drug Administration advisory panel recommended that "black-box" warnings on SSRIs be raised from 18 to 25 years old. The FDA is not obliged to follow the recommendations of its advisory committees but usually does.

Numerous articles - both scientific and accounts of individual cases of suicide and violence are available from many online sources which are not subject to accusations of financial conflicts of interest. An article first published by the American Psychiatric Association and now available through [SSRI Stories] states: "The CDC reports an increase in youth suicide from 2003 to 2004 and some "experts" are blaming this increase on the decline in antidepressant use among youth. However, the Black Box warning was not approved until September 2004 and, even then, it took months before the use of antidepressants among youth began to decline...Paragraph 11 reads: "In 2003, U.S. physicians wrote 15 million antidepressant prescriptions for patients under age 18, according to FDA data. In the first six months of 2004, antidepressant prescriptions for children increased by almost 8 percent, despite the new drug labeling."[30]

An October 2006 study promoted the idea that SSRIs may decrease youth suicide overall.[31] A more recent study [8] released in November 2006, however concluded only "The aggregate nature of these observational data precludes a direct causal interpretation of the results. More SSRI prescriptions... may reflect antidepressant efficacy".

According to these facts, antidepressant prescriptions for children increased by almost 8% in the first six months of 2004, if this is the case, it is difficult to link an increased suicide rate the same year to reduced use of antidepressants.

So despite the suggestions of a connection between the drop in SSRI prescriptions (even this fact is a matter of debate) and the spike in child and teen suicides, much more research will be needed before a conclusive link can be drawn.

In fact the only SSRI that is licensed for use in children in the UK and USA is Prozac. All other SSRIs have been banned from paediatric use as their safety and efficacy have not been proven. Even of its own paediatric trials of Seroxat, Glaxo said[9] “"The best which could have been achieved was a statement that although safety data was reassuring, efficacy had not been demonstrated."

A September 2007 study, to be published in American Journal of Psychiatry suggests newer antidepressants led to more suicides in teenagers.[32]

Fluoxetine and Suicide[edit | edit source]

The signs of violence and suicidality were there since the first SSRI antidepressant, Prozac (fluoxetine) was tested in premarketing trials.

In May 1984, Germany’s regulatory agency (G-BA) rejected Prozac as “totally unsuitable for treating depression.” In July 1985, Eli Lilly’s own data analysis—from a pool of 1,427 patients—showed high incidence of adverse drug effects and evidence of drug-induced violence in some patients.[33] In May 1985, FDA’s (then) chief safety investigator, Dr. Richard Kapit, wrote: “Unlike traditional tricyclic antidepressants fluoxetine’s profile of adverse side effects more closely resembles that of a stimulant drug than one that causes sedation.” He warned “It is fluoxetine’s particular profile of adverse side-effects which may perhaps, in the future give rise to the greatest clinical liabilities in the use of this medication to treat depression.”[34]

Dr. Kapit’s safety review described the clinical trial data from 46 trials with a total of 1,427 patients. He noted under the section, “Catastrophic and Serious Events,” 52 cases of “egregiously abnormal laboratory reports which were the reason for early termination,” and “additional adverse event reports not reported by the company [which] were revealed on microfiche.” Dr. Kapit reported: “In most cases, these adverse events involved the onset of an unreported psychotic episode.” There were 10 reports of psychotic episodes; 2 reports of completed suicides; 13 attempted suicides; 4 seizures—including a healthy volunteer; and 4 reports of movement disorders.

In 1985 Dr. Kapit recommended “labeling warning [for] the physician that such signs and symptoms of depression may be exacerbated by this drug". No such warning was issued until 2004.

Sertraline and Aggression[edit | edit source]

Pfizer’s data from the pediatric Zoloft (sertraline) trials shows that “aggression was the joint commonest cause for discontinuation from the two sertraline placebo-controlled trials in depressed children. In these trials, eight of 189 patients randomised to sertraline discontinued for aggression, agitation, or hyperkinesis, (otherwise known as akathisia) compared with no dropouts for these reasons in 184 patients on placebo. There were 15 discontinuations on Zoloft compared with two on placebo in any treatment induced manifestation of activation (i.e., suicidal ideation or attempts, aggression, agitation, hyperkinesis, or aggravated depression)". The published report failed to include this data in the analysis.[35]

Paroxetine and Aggression[edit | edit source]

In the trials posted on the GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) website, the authors note, “hostile events are found to excess in both adults and children on paroxetine compared with placebo, and are found across indications, and both on therapy and during withdrawal".[36]

The authors suggest that, perhaps the most significant evidence for drug-induced violence probably comes from healthy volunteer studies: hostile events occurred in three of 271 (1.1%) volunteers taking paroxetine, compared with zero in 138 taking placebo. By 2003, the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) received 121 cases of aggression on paroxetine, and by January 2006 that number had risen to 211.[37] Note, that estimates for such physician adverse drug effect reporting systems range between 1% and 10% of actual adverse effects on treatment.

Overdose[edit | edit source]

SSRIs appear to be safer in overdose when compared with traditional antidepressants such as the tricyclic antidepressants. This relative safety is supported both by case series and studies of deaths per numbers of prescriptions.[38] However, case reports of SSRI poisoning have indicated that severe toxicity can occur[39] and deaths have been reported following massive single ingestions,[40] although this is exceedingly uncommon when compared to the tricyclic antidepressants.[38]

Because of the wide therapeutic index of the SSRIs, most patients will have mild or no symptoms following moderate overdoses. The most commonly reported severe effect following SSRI overdose is serotonin syndrome; serotonin toxicity is usually associated with very high overdoses or multiple drug ingestion.[41] Other reported significant effects include coma, seizures, and cardiac toxicity.[38]

Treatment for SSRI overdose is mainly based on symptomatic and supportive care. Medical care may be required for agitation, maintenance of the airways, and treatment for serotonin syndrome. ECG monitoring is usually indicated to detect any cardiac abnormalities.

Criticism[edit | edit source]

Some feel that SSRIs are prescribed by overzealous doctors or psychiatrists in cases where their use is only marginally indicated. In late 2004 much media attention was given to a proposed link between SSRI use and juvenile suicide. For this reason, the use of SSRIs in pediatric cases of depression is now recognized by the FDA as warranting a cautionary statement to the parents of children who may be prescribed SSRIs by a family doctor. The FDA's currently required packaging insert for SSRIs includes a warning (known as a "black box warning") that a pooled analysis of placebo controlled trials of 9 antidepressant drugs (including multiple SSRIs) resulted in a risk of suicidality that was twice that of placebo. Other studies have shown no increase in rates of suicide but a small increase of non-fatal self-harm.[42]

Some critics of SSRIs claim that the widely-disseminated television and print advertising of SSRIs promotes an inaccurate message, oversimplifying what these medications actually do and deceiving the public.[43]

Much of the criticism stems from questions about the validity of claims that SSRIs work by 'correcting' chemical imbalances. Without accurately measuring patients' neurotransmitter levels to allow for continuous monitoring during treatment, it is impossible to know if one is correctly targeting a deficient neurotransmitter (i.e. correcting an imbalance), reaching a desirable level, or even introducing too much of a particular neurotransmitter. Thus it has been argued that SSRIs can actually cause chemical imbalances and abnormal brain states. Hence it is purported that when a patient discontinues an SSRI, they may have a chemical imbalance due to the rapid cessation of the drug which is causing the discontinuation syndrome.[44]

One possible mechanism is by inhibition of dopaminergic neurotransmission.[45]

Most biopsychiatrists believe that, among other factors, the balance of neurotransmitters in the brain is a biological regulator of mental health. In this theory, emotions within a "normal" spectrum reflect a proper balance of neurochemicals, but abnormally extreme emotions, such as clinical depression, reflect an imbalance. Psychiatrists claim that medications regulate neurotransmitters, and many if not most psychiatrists also claim they treat abnormal personalities by removing a neurochemical excess or replenishing a deficit (though the efficacy of antidepressants and antipsychotics is not undisputed[46]). On the other hand, Elliot Valenstein, a psychologist and neuroscientist, claims that the broad biochemical assertions and assumptions of mainstream psychiatry are not supported by evidence.[47]

One controversial critic of antidepressants, Peter Breggin, a physician who opposes the overuse of prescription medications to treat patients for mental health issues, predicted iatrogenic issues that SSRIs incur on a significant percentage of patients. Another prominent SSRI critic is David Healy.

Lawsuits[edit | edit source]

In one of the only three cases to ever go to trial for SSRI indication in suicide, Eli Lilly was caught corrupting the judicial process by making a deal with the plaintiff's attorney to throw the case, in part by not disclosing damaging evidence to the jury. The case, known as the Fentress Case involved a Kentucky man, Joseph Wesbecker, on Prozac, who went to his workplace and opened fire with an assault rifle killing 8 people (including Fentress), and injuring 12 others before turning the gun on himself. The jury returned a 9-to-3 verdict in favor of Lilly. The judge, in the end, took the matter to the Kentucky Supreme Court, which found that "there was a serious lack of candor with the trial court and there may have been deception, bad faith conduct, abuse of judicial process and, perhaps even fraud." The judge later revoked the verdict and instead, recorded the case as settled. The value of the secret settlement deal has never been disclosed, but was reportedly "tremendous".[48]

This case is said to be one of the most remembered cases involving SSRI's.

See also[edit | edit source]

- Neuropsychopharmacology

- Neuropharmacology

- Neurotoxicology

- Neuropsychotoxicology

- Pharmacology

- Psychoactive drug

- Serotonin/Norepinephrine/Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitor

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ (Chapter) Sheldon H. Preskorn, Christina Y. Stanga, Ruth Ross, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, p. 242 in Sheldon H. Preskorn, Christina Y. Stanga, John P. Feighner, Ruth Ross (Editors) (2004), Antidepressants: Past, Present, and Future, Springer, ISBN 3540430547

- ↑ PMID 17096399. Rasmussen-Torvik LJ, McAlpine DD. Genetic screening for SSRI drug response among those with major depression: great promise and unseen perils. Depress Anxiety. 2006 Nov 9

- ↑ PMID 14514498. Murphy GM Jr, Kremer C, Rodrigues HE, Schatzberg AF. Pharmacogenetics of antidepressant medication intolerance. Am J Psychiatry. 2003 Oct;160(10):1830-5.

- ↑ Malberg JE et al. (2000): "Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus" J. Neurosci. 20 (24), 9104-10

- ↑ O'Brien SM, Scully P, Scott LV, Dinan TG. "Cytokine profiles in bipolar affective disorder: focus on acutely ill patients." J Affect Disord. 2006 Feb;90(2-3):263-7.

- ↑ Obuchowicz E, Marcinowska A, Herman ZS. "Antidepressants and cytokines--clinical and experimental studies" Psychiatr Pol. 2005 Sep-Oct;39(5):921-36.

- ↑ Hong CJ, Yu YW, Chen TJ, Tsai SJ."Interleukin-6 genetic polymorphism and Chinese major depression". Neuropsychobiology. 2005;52(4):202-5.

- ↑ Elenkov IJ, Iezzoni DG, Daly A, Harris AG, Chrousos GP. "Abstract Cytokine dysregulation, inflammation and well-being". Neuroimmunomodulation. 2005;12(5):255-69

- ↑ Kubera M, Maes M, Kenis G, Kim YK, Lason W. "Effects of serotonin and serotonergic agonists and antagonists on the production of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6" Psychiatry Res. 2005 Apr 30;134(3):251-8.

- ↑ Diamond M, Kelly JP, Connor TJ. "Antidepressants suppress production of the Th1 cytokine interferon-gamma, independent of monoamine transporter blockade". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006 Oct;16(7):481-90.

- ↑ Kubera M, Lin AH, Kenis G, Bosmans E, van Bockstaele D, Maes M. "Anti-Inflammatory effects of antidepressants through suppression of the interferon-gamma/interleukin-10 production ratio." J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001 Apr;21(2):199-206

- ↑ Maes M."The immunoregulatory effects of antidepressants". Hum Psychopharmacol. 2001 Jan;16(1):95-103

- ↑ Maes M, Kenis G, Kubera M, De Baets M, Steinbusch H, Bosmans E."The negative immunoregulatory effects of fluoxetine in relation to the cAMP-dependent PKA pathway". Int Immunopharmacol. 2005 Mar;5(3):609-18.

- ↑ O'Brien SM, Scott LV, Dinan TG. "Cytokines: abnormalities in major depression and implications for pharmacological treatment". Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004 Aug;19(6):397-403.

- ↑ Anderson IM (2000): "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability", J. Affect. Disord. 58(1), 19-3

- ↑ Hu XH; et al. (2004). "Incidence and duration of side effects and those rated as bothersome with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment for depression: patient report versus physician estimate". J Clin Psychiatry. 65: 959–65. PMID 15291685.

- ↑ Landen M, Hogberg P, Thase ME (2005). "Incidence of sexual side effects in refractory depression during treatment with citalopram or paroxetine". J Clin Psychiatry. 66: 100–6. PMID 15669895.

- ↑ Waldinger MD, Olivier B. (July), "Utility of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in premature ejaculation", Curr Opin Investig Drugs, 5 (7): 743–7, PMID 15298071 Check date values in:

|date=, |year= / |date= mismatch(help) - ↑ Pacher P, Kecskemeti V."Cardiovascular side effects of new antidepressants and antipsychotics: new drugs, old concerns?". Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10(20):2463-2475. PMID 15320756

- ↑ Grace Brooke Huffman. "Cardiac effects in patients using SSRI antidepressants - selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor - Tips from Other Journals". American Family Physician, August, 1997.

- ↑ Pacher P, Ungvari Z, Nanasi PP, Furst S, Kecskemeti V."Speculations on difference between tricyclic and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants on their cardiac effects. Is there any?". Curr Med Chem. 1999 Jun;6(6):469-80. PMID 10213794

- ↑ [1]Richard J. Goldberg, MD. Selective "Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors: Infrequent Medical Adverse Effects". Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:78-84.

- ↑ [2] FDA Public Health Advisory - Treatment Challenges of Depression in Pregnancy

- ↑ [3] Medical News Today - Lancet Press Release. Feb 05 2005

- ↑ Cohen, MD, Lee S. (February 1, 2006). "Relapse of Major Depression During Pregnancy in Women Who Maintain or Discontinue Antidepressant Treatment". Journal of the American Medical Association. American Medical Association. 295 (5): 499–507. Retrieved 2007-06-14. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ "Relapse of Major Depression During Pregnancy in Women Who Maintain or Discontinue Antidepressant Treatment—Correction". JAMA. 296 (2): 170. July 12, 2006. Retrieved 2007-06-14. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ David Armstrong, "Drug Interactions: Financial Ties to Industry Cloud Major Depression Study At Issue: Whether It's Safe For Pregnant Women To Stay on Medication - JAMA Asks Authors to Explain". Wall Street Journal. July 11, 2006 (copy published on post-gazette.com)

- ↑ Overview SSRI antidepressants. Paxil

- ↑ SSRI Induced Suicide: A Review

- ↑ psychiatry online

- ↑ SSRI S APPEAR TO DECREASE YOUTH SUICIDE OVERALL October 2006

- ↑ Template:Web cite

- ↑ Eli Lilly internal analysis submitted to the Joachim Wernicke (July 2, 1985), PZ 2441 2000. Document uncovered during Fentress litigation.

- ↑ Kapit R. FDA Safety Review NDA 18-963, March 23, 1985.

- ↑ Wagner KD, Ambrosini P, Rynn M, Wohlberg C, Yang R, et al. (2003) Effi cacy of sertraline in the treatment of children and adolescents with major depressive disorder: Two randomized controlled trials. JAMA 290: 1033–1041.

- ↑ [4]www.paxil.com

- ↑ [5] Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (2006) Adverse drug reactions online information tracking: Drug analysis print

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Isbister G, Bowe S, Dawson A, Whyte I (2004). "Relative toxicity of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in overdose". J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 42 (3): 277–85. PMID 15362595.

- ↑ Borys D, Setzer S, Ling L, Reisdorf J, Day L, Krenzelok E (1992). "Acute fluoxetine overdose: a report of 234 cases". Am J Emerg Med. 10 (2): 115–20. PMID 1586402.

- ↑ Oström M, Eriksson A, Thorson J, Spigset O (1996). "Fatal overdose with citalopram". Lancet. 348 (9023): 339–40. PMID 8709713.

- ↑ Sporer K (1995). "The serotonin syndrome. Implicated drugs, pathophysiology and management". Drug Saf. 13 (2): 94–104. PMID 7576268.

- ↑ Gunnell D, Saperia J, Ashby D. "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide in adults: meta-analysis of drug company data from placebo controlled, randomised controlled trials submitted to the MHRA's".

- ↑ Lacasse JR, Leo J. Serotonin and Depression: A Disconnect between the Advertisements and the Scientific Literature. PLoS Medicine 2005;2:e392.

- ↑ Moncrieff J, Cohen D. Do Antidepressants Cure or Create Abnormal Brain States? PLoS Medicine 2006;3:e240.

- ↑ Damsa C, Bumb A, Bianchi-Demicheli F, Vidailhet P, Sterck R, Andreoli A, Beyenburg S. "Dopamine-dependent" side effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a clinical review". J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1064-8. PMID 15323590.

- ↑ http://www.breggin.com/prbbooks.html

- ↑ Valenstein, Elliot (1998). Blaming the Brain: The Truth about Drugs and Mental Health. The Free Press.

- ↑ [6] from Richard Zitrin & Carol M. Langford. "Hide and Secrets in Louisville" from "The Moral Compass of the American Lawyer". Ballantine Books, 1999

Template:Antidepressants Template:Receptor agonists and antagonists

da:Lykkepille de:Serotonin-Wiederaufnahmehemmer it:SSRI he:SSRI lt:SSRI hu:Szelektív szerotonin-visszavétel gátlók nl:Selective Serotinine Reuptake Inhibitor no:Selektiv serotoninreopptakshemmer fi:Selektiivinen serotoniinin takaisinoton estäjä sv:SSRI

KSF

KSF