Stem cell

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 16 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 16 min

|

WikiDoc Resources for Stem cell |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Stem cell |

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Stem cell at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Stem cell at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Stem cell

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Stem cell Discussion groups on Stem cell Directions to Hospitals Treating Stem cell Risk calculators and risk factors for Stem cell

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Stem cell |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

For The WikiDoc Living Textbook Of Stem Cell Therapy Directory click here

Editor-in-Chief: Robert G. Schwartz, M.D. [5], Piedmont Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, P.A.;

Overview[edit | edit source]

Stem cells are cells found in most, if not all, multi-cellular organisms. They are characterized by the ability to renew themselves through mitotic cell division and differentiating into a diverse range of specialized cell types. Research in the stem cell field grew out of findings by Canadian scientists Ernest A. McCulloch and James E. Till in the 1960s.[1][2] The two broad types of mammalian stem cells are: embryonic stem cells that are found in blastocysts, and adult stem cells that are found in adult tissues. In a developing embryo, stem cells can differentiate into all of the specialized embryonic tissues. In adult organisms, stem cells and progenitor cells act as a repair system for the body, replenishing specialized cells, but also maintain the normal turnover of regenerative organs, such as blood, skin or intestinal tissues.

As stem cells can be grown and transformed into specialized cells with characteristics consistent with cells of various tissues such as muscles or nerves through cell culture, their use in medical therapies has been proposed. In particular, embryonic cell lines, autologous embryonic stem cells generated through therapeutic cloning, and highly plastic adult stem cells from the umbilical cord blood or bone marrow are touted as promising candidates.[3]

Properties of stem cells[edit | edit source]

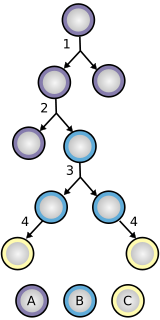

The classical definition of a stem cell requires that it possess two properties:

- Self-renewal - the ability to go through numerous cycles of cell division while maintaining the undifferentiated state.

- Potency - the capacity to differentiate into specialized cell types. In the strictest sense, this requires stem cells to be either totipotent or pluripotent - to be able to give rise to any mature cell type, although multipotent or unipotent progenitor cells are sometimes referred to as stem cells.

Potency definitions[edit | edit source]

Potency specifies the differentiation potential (the potential to differentiate into different cell types) of the stem cell.

- Totipotent stem cells are produced from the fusion of an egg and sperm cell. Cells produced by the first few divisions of the fertilized egg are also totipotent. These cells can differentiate into embryonic and extraembryonic cell types.

- Pluripotent stem cells are the descendants of totipotent cells and can differentiate into cells derived from any of the three germ layers.

- Multipotent stem cells can produce only cells of a closely related family of cells (e.g. hematopoietic stem cells differentiate into red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, etc.).

- Unipotent cells can produce only one cell type, but have the property of self-renewal which distinguishes them from non-stem cells (e.g. muscle stem cells).

Identifying stem cells[edit | edit source]

The practical definition of a stem cell is the functional definition - the ability to regenerate tissue over a lifetime. For example, the gold standard test for a bone marrow or hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) is the ability to transplant one cell and save an individual without HSCs. In this case, a stem cell must be able to produce new blood cells and immune cells over a long term, demonstrating potency. It should also be possible to isolate stem cells from the transplanted individual, which can themselves be transplanted into another individual without HSCs, demonstrating that the stem cell was able to self-renew.

Properties of stem cells can be illustrated in vitro, using methods such as clonogenic assays, where single cells are characterized by their ability to differentiate and self-renew.[4][5] As well, stem cells can be isolated based on a distinctive set of cell surface markers. However, in vitro culture conditions can alter the behavior of cells, making it unclear whether the cells will behave in a similar manner in vivo. Considerable debate exists whether some proposed adult cell populations are truly stem cells.

Embryonic stem cells[edit | edit source]

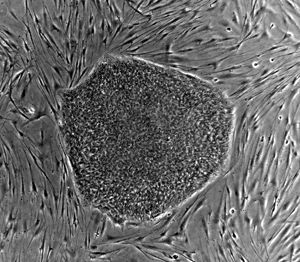

Embryonic stem cell lines (ES cell lines) are cultures of cells derived from the epiblast tissue of the inner cell mass (ICM) of a blastocyst or earlier morula stage embryos.[6] A blastocyst is an early stage embryo—approximately four to five days old in humans and consisting of 50–150 cells. ES cells are pluripotent and give rise during development to all derivatives of the three primary germ layers: ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm. In other words, they can develop into each of the more than 200 cell types of the adult body when given sufficient and necessary stimulation for a specific cell type. They do not contribute to the extra-embryonic membranes or the placenta.

Nearly all research to date has taken place using mouse embryonic stem cells (mES) or human embryonic stem cells (hES). Both have the essential stem cell characteristics, yet they require very different environments in order to maintain an undifferentiated state. Mouse ES cells are grown on a layer of gelatin and require the presence of Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF).[7] Human ES cells are grown on a feeder layer of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and require the presence of basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF or FGF-2).[8] Without optimal culture conditions or genetic manipulation,[9] embryonic stem cells will rapidly differentiate.

A human embryonic stem cell is also defined by the presence of several transcription factors and cell surface proteins. The transcription factors Oct-4, Nanog, and SOX2 form the core regulatory network that ensures the suppression of genes that lead to differentiation and the maintenance of pluripotency.[10] The cell surface antigens most commonly used to identify hES cells are the glycolipids SSEA3 and SSEA4 and the keratan sulfate antigens Tra-1-60 and Tra-1-81. The molecular definition of a stem cell includes many more proteins and continues to be a topic of research.[11]

After twenty years of research, there are no approved treatments or human trials using embryonic stem cells. ES cells, being totipotent cells, require specific signals for correct differentiation - if injected directly into the body, ES cells will differentiate into many different types of cells, causing a teratoma. Differentiating ES cells into usable cells while avoiding transplant rejection are just a few of the hurdles that embryonic stem cell researchers still face.[12] Many nations currently have moratoria on either ES cell research or the production of new ES cell lines. Because of their combined abilities of unlimited expansion and pluripotency, embryonic stem cells remain a theoretically potential source for regenerative medicine and tissue replacement after injury or disease.

Adult stem cells[edit | edit source]

The term adult stem cell refers to any cell which is found in a developed organism that has two properties: the ability to divide and create another cell like itself and also divide and create a cell more differentiated than itself. Also known as somatic (from Greek Σωματικóς, "of the body") stem cells and germline (giving rise to gametes) stem cells, they can be found in children, as well as adults.[13] Pluripotent adult stem cells are rare and generally small in number but can be found in a number of tissues including umbilical cord blood.[14] Most adult stem cells are lineage-restricted (multipotent) and are generally referred to by their tissue origin (mesenchymal stem cell, adipose-derived stem cell, endothelial stem cell, etc.).[15][16]

A great deal of adult stem cell research has focused on clarifying their capacity to divide or self-renew indefinitely and their differentiation potential.[17] In mice, pluripotent stem cells are directly generated from adult fibroblast cultures.[18]

While embryonic stem cell potential remains untested, adult stem cell treatments have been used for many years to treat successfully leukemia and related bone/blood cancers through bone marrow transplants.[19] The use of adult stem cells in research and therapy is not as controversial as embryonic stem cells, because the production of adult stem cells does not require the destruction of an embryo. Consequently, more US government funding is being provided for adult stem cell research.[20]

Lineage[edit | edit source]

To ensure self-renewal, stem cells undergo two types of cell division (see Stem cell division and differentiation diagram). Symmetric division gives rise to two identical daughter cells both endowed with stem cell properties. Asymmetric division, on the other hand, produces only one stem cell and a progenitor cell with limited self-renewal potential. Progenitors can go through several rounds of cell division before terminally differentiating into a mature cell. It is possible that the molecular distinction between symmetric and asymmetric divisions lies in differential segregation of cell membrane proteins (such as receptors) between the daughter cells.[21]

An alternative theory is that stem cells remain undifferentiated due to environmental cues in their particular niche. Stem cells differentiate when they leave that niche or no longer receive those signals. Studies in Drosophila germarium have identified the signals dpp and adherins junctions that prevent germarium stem cells from differentiating.[22][23]

The signals that lead to reprogramming of cells to an embryonic-like state are also being investigated. These signal pathways include several transcription factors including the oncogene c-Myc. Initial studies indicate that transformation of mice cells with a combination of these anti-differentiation signals can reverse differentiation and may allow adult cells to become pluripotent.[24] However, the need to transform these cells with an oncogene may prevent the use of this approach in therapy.

Treatments[edit | edit source]

Medical researchers believe that stem cell therapy has the potential to dramatically change the treatment of human disease. A number of adult stem cell therapies already exist, particularly bone marrow transplants that are used to treat leukemia.[25] In the future, medical researchers anticipate being able to use technologies derived from stem cell research to treat a wider variety of diseases including cancer, Parkinson's disease, spinal cord injuries, and muscle damage, amongst a number of other impairments and conditions.[26][27]

Stem Cell treatments are becoming more widely available, especially for musculoskeletal, peripheral vascular, and peripheral neuropathy indications. Most clinical applications use autologous stem cells and do not involve manipulation of the cells in between harvesting and implantation [6]. Several factors influence the selection of autologus stem cell harvest site and type. In those cases where autologous harvest does not make sense then placental derived cells is a viable alternative.

Other uses for stem cell are still surrounded scientific uncertainty but are gaining in acceptance. While stem cells are already used extensively in research some scientists do not see cell therapy as the first goal of the research, but see the investigation of stem cells as a goal worthy in itself.[28]

Controversy surrounding human embryonic stem cell research[edit | edit source]

There exists a widespread controversy over human embryonic stem cell research that emanates from the techniques used in the creation and usage of stem cells. Human embryonic stem cell research is controversial because, with the present state of technology, starting a stem cell line requires the destruction of a human embryo and/or therapeutic cloning. However, recently, it has been shown in principle that embryonic stem cell lines can be generated using a single-cell biopsy similar to that used in preimplantation genetic diagnosis that may allow stem cell creation without embryonic destruction.[29] It is not the entire field of stem cell research, but the specific field of human embryonic stem cell research that is at the centre of an ethical debate.

Opponents of the research argue that embryonic stem cell technologies are a slippery slope to reproductive cloning and can fundamentally devalue human life. Those in the pro-life movement argue that a human embryo is a human life and is therefore entitled to protection.

Contrarily, supporters of embryonic stem cell research argue that such research should be pursued because the resultant treatments could have significant medical potential. It is also noted that excess embryos created for in vitro fertilisation could be donated with consent and used for the research.

The ensuing debate has prompted authorities around the world to seek regulatory frameworks and highlighted the fact that stem cell research represents a social and ethical challenge.

Key stem cell research events[edit | edit source]

- 1960s - Joseph Altman and Gopal Das present scientific evidence of adult neurogenesis, ongoing stem cell activity in the brain; their reports contradict Cajal's "no new neurons" dogma and are largely ignored.

- 1963 - McCulloch and Till illustrate the presence of self-renewing cells in mouse bone marrow.

- 1968 - Bone marrow transplant between two siblings successfully treats SCID.

- 1978 - Haematopoietic stem cells are discovered in human cord blood.

- 1981 - Mouse embryonic stem cells are derived from the inner cell mass by scientists Martin Evans, Matthew Kaufman, and Gail R. Martin. Gail Martin is attributed for coining the term "Embryonic Stem Cell".

- 1992 - Neural stem cells are cultured in vitro as neurospheres.

- 1997 - Leukemia is shown to originate from a haematopoietic stem cell, the first direct evidence for cancer stem cells.

- 1998 - James Thomson and coworkers derive the first human embryonic stem cell line at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- 2000s - Several reports of adult stem cell plasticity are published.

- 2001 - Scientists at Advanced Cell Technology clone first early (four- to six-cell stage) human embryos for the purpose of generating embryonic stem cells.[30]

- 2003 - Dr. Songtao Shi of NIH discovers new source of adult stem cells in children's primary teeth.[31]

- 2004-2005 - Korean researcher Hwang Woo-Suk claims to have created several human embryonic stem cell lines from unfertilised human oocytes. The lines were later shown to be fabricated.

- 2005 - Researchers at Kingston University in England claim to have discovered a third category of stem cell, dubbed cord-blood-derived embryonic-like stem cells (CBEs), derived from umbilical cord blood. The group claims these cells are able to differentiate into more types of tissue than adult stem cells.

- August 2006 - Rat Induced pluripotent stem cells: the journal Cell publishes Kazutoshi Takahashi and Shinya Yamanaka, "Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors".

- October 2006 - Scientists in England create the first ever artificial liver cells using umbilical cord blood stem cells.[32][33]

- January 2007 - Scientists at Wake Forest University led by Dr. Anthony Atala and Harvard University report discovery of a new type of stem cell in amniotic fluid.[7] This may potentially provide an alternative to embryonic stem cells for use in research and therapy.[34]

- June 2007 - Research reported by three different groups shows that normal skin cells can be reprogrammed to an embryonic state in mice.[35] In the same month, scientist Shoukhrat Mitalipov reports the first successful creation of a primate stem cell line through somatic cell nuclear transfer[36]

- October 2007 - Mario Capecchi, Martin Evans, and Oliver Smithies win the 2007 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for their work on embryonic stem cells from mice using gene targeting strategies producing genetically engineered mice (known as knockout mice) for gene research.[37]

- November 2007 - Human Induced pluripotent stem cells: Two similar papers released by their respective journals prior to formal publication: in Cell by Kazutoshi Takahashi and Shinya Yamanaka, "Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors", and in Science by Junying Yu, et al., from the research group of James Thomson, "Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Lines Derived from Human Somatic Cells": pluripotent stem cells generated from mature human fibroblasts. It is possible now to produce a stem cell from almost any other human cell instead of using embryos as needed previously, albeit the risk of tumorigenesis due to c-myc and retroviral gene transfer remains to be determined.

- January 2008 - Human embryonic stem cell lines were generated without destruction of the embryo[38]

- January 2008 - Development of human cloned blastocysts following somatic cell nuclear transfer with adult fibroblasts[39]

- February 2008 - Generation of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Mouse Liver and Stomach: these iPS cells seem to be more similar to embryonic stem cells than the previous developed iPS cells and not tumorigenic, moreover genes that are required for iPS cells do not need to be inserted into specific sites, which encourages the development of non-viral reprogramming techniques. [40][41]

Stem cell funding & policy debate in the US[edit | edit source]

- 1993 - As per the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act, Congress and President Bill Clinton give the NIH direct authority to fund human embryo research for the first time.[42]

- 1995 - The U.S. Congress enacts into law an appropriations bill attached to which is the Dickey Amendment which prohibited federally appropriated funds to be used for research where human embryos would be either created or destroyed. This predates the creation of the first human embryonic stem cell lines.

- 1999 - After the creation of the first human embryonic stem cell lines in 1998 by James Thomson of the University of Wisconsin, Harriet Rabb, the top lawyer at the Department of Health and Human Services, releases a legal opinion that would set the course for Clinton Administration policy. Federal funds, obviously, could not be used to derive stem cell lines (because derivation involves embryo destruction). However, she concludes that because human embryonic stem cells "are not a human embryo within the statutory definition," the Dickey-Wicker Amendment does not apply to them. The NIH was therefore free to give federal funding to experiments involving the cells themselves. President Clinton strongly endorses the new guidelines, noting that human embryonic stem cell research promised "potentially staggering benefits." And with the guidelines in place, the NIH begins accepting grant proposals from scientists.[43]

- 02 November, 2004 - California voters approve Proposition 71, which provides $3 billion in state funds over ten years to human embryonic stem cell research.

- 2001-2006 - U.S. President George W. Bush signs an executive order which restricts federally-funded stem cell research on embryonic stem cells to the already derived cell lines. He supports federal funding for embryonic stem cell research on the already existing lines of approximately $100 million and $250 million for research on adult and animal stem cells.

- 5 May, 2006 - Senator Rick Santorum introduces bill number S. 2754, or the Alternative Pluripotent Stem Cell Therapies Enhancement Act, into the U.S. Senate.

- 18 July, 2006 - The U.S. Senate passes the Stem Cell Research Enhancement Act H.R. 810 and votes down Senator Santorum's S. 2754.

- 19 July, 2006 - President George W. Bush vetoes H.R. 810 (Stem Cell Research Enhancement Act), a bill that would have reversed the Gingrich-era appropriations amendment which made it illegal for federal money to be used for research where stem cells are derived from the destruction of an embryo.

- 07 November, 2006 - The people of the U.S. state of Missouri passed Amendment 2, which allows usage of any stem cell research and therapy allowed under federal law, but prohibits human reproductive cloning.[44]

- 16 February, 2007 – The California Institute for Regenerative Medicine became the biggest financial backer of human embryonic stem cell research in the United States when they awarded nearly $45 million in research grants.[45]

Related Chapters[edit | edit source]

- The American Society for Cell Biology

- California Institute for Regenerative Medicine

- Genetics Policy Institute

- Cancer stem cells

- Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPS Cell)

- Odontis

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Becker AJ, McCulloch EA, Till JE (1963). "Cytological demonstration of the clonal nature of spleen colonies derived from transplanted mouse marrow cells". Nature. 197: 452–4. doi:10.1038/197452a0. PMID 13970094.

- ↑ Siminovitch L, McCulloch EA, Till JE (1963). "The distribution of colony-forming cells among spleen colonies". Journal of Cellular and Comparative Physiology. 62: 327–36. doi:10.1002/jcp.1030620313. PMID 14086156.

- ↑ Tuch BE (2006). "Stem cells--a clinical update". Australian family physician. 35 (9): 719–21. PMID 16969445.

- ↑ Friedenstein AJ, Deriglasova UF, Kulagina NN, Panasuk AF, Rudakowa SF, Luria EA, Ruadkow IA (1974). "Precursors for fibroblasts in different populations of hematopoietic cells as detected by the in vitro colony assay method". Exp Hematol. 2 (2): 83–92. PMID 4455512.

- ↑ Friedenstein AJ, Gorskaja JF, Kulagina NN (1976). "Fibroblast precursors in normal and irradiated mouse hematopoietic organs". Exp Hematol. 4 (5): 267–74. PMID 976387.

- ↑ FOXNews.com - New Stem-Cell Procedure Doesn't Harm Embryos, Company Claims - Biology | Astronomy | Chemistry | Physics

- ↑ [1] , Mouse Embryonic Stem (ES) Cell Culture-Current Protocols in Molecular Biology

- ↑ [2], Culture of Human Embryonic Stem Cells (hESC) NIH

- ↑ Chambers I, Colby D, Robertson M; et al. (2003). "Functional expression cloning of Nanog, a pluripotency sustaining factor in embryonic stem cells". Cell. 113 (5): 643–55. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00392-1. PMID 12787505.

- ↑ Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF; et al. (2005). "Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells". Cell. 122 (6): 947–56. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. PMID 16153702.

- ↑ Adewumi O, Aflatoonian B, Ahrlund-Richter L; et al. (2007). "Characterization of human embryonic stem cell lines by the International Stem Cell Initiative". Nat. Biotechnol. 25 (7): 803–16. doi:10.1038/nbt1318. PMID 17572666.

- ↑ Wu DC, Boyd AS, Wood KJ (2007). "Embryonic stem cell transplantation: potential applicability in cell replacement therapy and regenerative medicine". Front. Biosci. 12: 4525–35. doi:10.2741/2407. PMID 17485394.

- ↑ Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL; et al. (2002). "Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow". Nature. 418 (6893): 41–9. doi:10.1038/nature00870. PMID 12077603.

- ↑ Ratajczak MZ, Machalinski B, Wojakowski W, Ratajczak J, Kucia M (2007). "A hypothesis for an embryonic origin of pluripotent Oct-4(+) stem cells in adult bone marrow and other tissues". Leukemia. 21 (5): 860–7. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2404630. PMID 17344915.

- ↑ Barrilleaux B, Phinney DG, Prockop DJ, O'Connor KC (2006). "Review: ex vivo engineering of living tissues with adult stem cells". Tissue Eng. 12 (11): 3007–19. doi:10.1089/ten.2006.12.3007. PMID 17518617.

- ↑ Gimble JM, Katz AJ, Bunnell BA (2007). "Adipose-derived stem cells for regenerative medicine". Circ. Res. 100 (9): 1249–60. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000265074.83288.09. PMID 17495232.

- ↑ Gardner RL (2002). "Stem cells: potency, plasticity and public perception". Journal of Anatomy. 200 (3): 277–82. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00029.x. PMID 12033732.

- ↑ Takahashi K, Yamanaka S (2006). "Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors". Cell. 126 (4): 663–76. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. PMID 16904174.

- ↑ [3], Bone Marrow Transplant

- ↑ [4],USDHHS Stem Cell FAQ 2004

- ↑ Beckmann J, Scheitza S, Wernet P, Fischer JC, Giebel B (2007). "Asymmetric cell division within the human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell compartment: identification of asymmetrically segregating proteins". Blood. 109 (12): 5494–501. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-11-055921. PMID 17332245.

- ↑ Xie T, Spradling A (1998). "decapentaplegic is essential for the maintenance and division of germline stem cells in the Drosophila ovary". Cell. 94 (2): 251–60. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81424-5. PMID 9695953.

- ↑ Song X, Zhu C, Doan C, Xie T (2002). "Germline stem cells anchored by adherens junctions in the Drosophila ovary niches". Science. 296 (5574): 1855–7. doi:10.1126/science.1069871. PMID 12052957.

- ↑ Takahashi K, Yamanaka S (2006). "Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors". Cell. 126 (4): 663–76. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. PMID 16904174.

- ↑ Gahrton G, Björkstrand B (2000). "Progress in haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma". J Intern Med. 248 (3): 185–201. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00706.x. PMID 10971785.

- ↑ Lindvall O (2003). "Stem cells for cell therapy in Parkinson's disease". Pharmacol Res. 47 (4): 279–87. doi:10.1016/S1043-6618(03)00037-9. PMID 12644384.

- ↑ Goldman S, Windrem M (2006). "Cell replacement therapy in neurological disease". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 361 (1473): 1463–75. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1886. PMID 16939969.

- ↑ Wade N (2006-08-14). "Some Scientists See Shift in Stem Cell Hopes". New York Times. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

- ↑ Firm Creates Stem Cells Without Hurting Embryos : NPR

- ↑ The First Human Cloned Embryo: Scientific American

- ↑ Shostak S (2006). "(Re)defining stem cells". Bioessays. 28 (3): 301–8. doi:10.1002/bies.20376. PMID 16479584.

- ↑ Good News for Alcoholics | Biotechnology | DISCOVER Magazine

- ↑ Scotsman.com News

- ↑ Amniotic fluid yields stem cells, Harvard researchers report - Boston.com

- ↑ Cyranoski D (2007). "Simple switch turns cells embryonic". Nature. 447 (7145): 618–9. doi:10.1038/447618a. PMID 17554270.

- ↑ Mitalipov SM, Zhou Q, Byrne JA, Ji WZ, Norgren RB, Wolf DP (2007). "Reprogramming following somatic cell nuclear transfer in primates is dependent upon nuclear remodeling". Hum Reprod. 22 (8): 2232–42. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem136. PMID 17562675.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2007". Nobelprize.org. Unknown parameter

|accessdaymonth=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ↑ Cell Stem Cell - Chung et al

- ↑ http://stemcells.alphamedpress.org/cgi/reprint/2007-0252v1.pdf

- ↑ Generation of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Mo...[Science. 2008] - PubMed Result

- ↑ The Niche: Adult cell types besides skin are reprogrammed

- ↑ Dispatches: The Politics of Stem Cells PBS

- ↑ Dispatches: The Politics of Stem Cells PBS

- ↑ Full-text of Missouri Constitution Amendment 2

- ↑ Calif. Awards $45M in Stem Cell Grants Associated Press, Feb. 17, 2007.

External links[edit | edit source]

- General

- Tell Me About Stem Cells: Quick and simple guide explaining the science behind stem cells

- Stem Cell Basics

- Nature Reports Stem Cells: Introductory material, research advances and debates concerning stem cell research.

- Understanding Stem Cells: A View of the Science and Issues from the National Academies

- Scientific American Magazine (June 2004 Issue) The Stem Cell Challenge

- Scientific American Magazine (July 2006 Issue) Stem Cells: The Real Culprits in Cancer?

- National Institutes of Health

- Stem Cell Research Forum of India

- Template:Sep entry

- Peer-reviewed journals

- STEM CELLS®

- Cytotherapy

- Cloning and Stem Cells

- Stem Cells and Development

- Regenerative Medicine

- Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy

Template:Stem cells Template:Embryology

af:Stamsel ar:خلايا جذعية bg:Стволова клетка ca:Cèl·lula mare cs:Kmenová buňka da:Stamcelle de:Stammzelle et:Tüvirakud eo:Praĉelo fa:سلولهای بنیادی ko:줄기 세포 id:Sel induk it:Cellula staminale he:תא גזע ka:ღეროვანი უჯრედი lt:Kamieninė ląstelė nl:Stamcel no:Stamcelle sr:Изворна ћелија fi:Kantasolu sv:Stamcell ta:குருத்துத் திசுள் th:สเต็มเซลล์ uk:Стовбурні клітини ur:خلیہ جذعیہ yi:סטעם צעל

KSF

KSF