Stent

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 9 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 9 min

|

WikiDoc Resources for Stent |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Stent at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Stent at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Stent

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Stent Risk calculators and risk factors for Stent

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview[edit | edit source]

In medicine, a stent is a tube that is inserted into a natural conduit of the body to prevent or counteract a disease-induced localized flow constriction. The term may also refer to a tube used to temporarily hold such a natural conduit open to allow access for surgery.

Applications[edit | edit source]

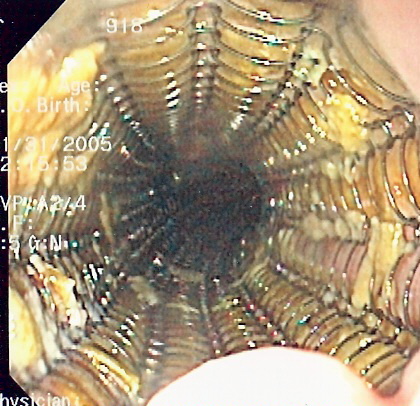

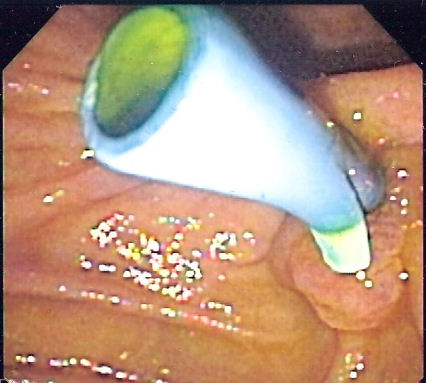

The main purpose of a stent is to counteract significant decreases in vessel or duct diameter by acutely propping open the conduit by a mechanical scaffold or stent. Stents are often used to alleviate diminished blood flow to organs and extremities beyond an obstruction in order to maintain an adequate delivery of oxygenated blood. Although the most widely known use of stents is in coronary arteries, they are widely used in other natural body conduits, such as central and peripheral arteries and veins, bile ducts, esophagus, colon, trachea or large bronchi, ureters, and urethra.

Etymology[edit | edit source]

The origin of the word stent remains unsettled. The verb stenting was used for centuries for the process of stiffening garments (a usage long obsolete, per the Oxford English Dictionary) and some believe this to be the origin. Others attribute the noun stent to Jan F. Esser, a Dutch plastic surgeon who in 1916 used the word to describe a dental impression compound invented in 1856 by the English dentist Charles Stent (1807–1885), which Esser employed to craft a form for facial reconstruction. The full account is described in the Journal of the History of Dentistry. [2] According to the author, from the use of Stent's compound as support for facial tissues grew the eventual use of stent to open various bodily structures. Worth noting though is that the first "stents" used in medical practice were initially called "Wallstents".

Types of stent[edit | edit source]

Vascular[edit | edit source]

- Bare Metal Stent

- Covered Stent and Stent Graft

- Drug-eluting stent

- First generation stents eluted sirolimus (SES) or paclitaxel (PES)[1]

- Second generation stents are zotarolimus-eluting stent (ZES) and the everolimus-eluting stent (EES). Everolimus (a semi-synthetic derivative of sirolimus). Second generation stents have other enhancements in addition to the choice of drug.

In the controlled environment of randomized clinical trials, routine coronary stenting is safe but probably not associated with important reductions in rates of mortality, acute myocardial infarction, or coronary artery bypass surgery compared with standard PTCA with provisional stenting. Coronary stenting is associated with substantial reductions in angiographic restenosis rates and the subsequent need for repeated PTCA, although this benefit may be overestimated because of trial designs. The incremental benefit of routine stenting for reducing repeated angioplasty diminishes as the crossover rate of stenting with conventional PTCA increases.[2]

Stent implantation versus Coronary bypass surgery[edit | edit source]

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world, and both surgical revascularisation (coronary artery bypass grafting, CABG) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are established treatment options. The rapid developments in both surgical and percutaneous techniques have been such that the choice of the optimum revascularisation strategy is changing, often without an established evidence base; this is particularly true in complex conditions including patients with three-vessel and left main stem anatomy. The widespread use of drug eluting stents has resulted in a significant reduction in patients referred for CABG although published data favours the surgical approach in this high-risk group.

- The SYNTAX Trial[3] aims to explore the interface between treatment with CABG and PCI in patients with three-vessel and left main stem disease, comparing CABG using contemporary techniques and PCI using drug eluting TAXUS stents. The aim of the trial is to establish non-inferiority of PCI with CABG. The unique feature of the SYNTAX trial is the ‘all comers’ strategy. A team comprising a cardiac surgeon and an interventional cardiologist assesses each patient; if equivalent revascularisation is applicable using both techniques, the patient is accepted for randomization; if either CABG or PCI is deemed unsuitable for technical reasons or the presence of co-morbidities, then the patient is recruited into one of two parallel registries which will track these patients undergoing either CABG or PCI. The patient will not be included in the randomized cohort. 1800 patients will be randomized (1:1) between CABG and PCI. The primary end-point is a major adverse, cardiac and cerbrovascular event at one year. All patients will be followed for five years. Of the 1800 patients, 710 with left main stem disease will be randomized between CABG and PCI. In this sub-group, repeat cardiac catheterisation will be undertaken after the one-year primary endpoint to determine graft and native vessel patency (the Le Mans sub-study).

- The SYNTAX Trial is one of the most important trials ever undertaken in the field of coronary revascularisation and will provide a rational basis for choosing the optimum revascularisation strategy in patients for many years to come.

- Problems: One of the drawbacks of vascular stents is the potential development of a thick smooth muscle tissue inside the lumen, the so-called neointima. Development of a neointima is variable but can at times be so severe as to re-occlude the vessel lumen (restenosis), especially in the case of smaller diameter vessels, which often results in reintervention. Consequently, current research focuses on the reduction of neointima after stent placement. Considerable improvements have been made, including the use of more bio-compatible materials, anti-inflammatory drug-eluting stents, resorbable stents, and others. Fortunately, even if stents are eventually covered by neointima, the minimally invasive nature of their deployment makes reintervention possible and usually straightforward.

- On September 4, 2007, an international study showed that some heart attack patients would be better off without using drug-coated stents in emergency to open their clogged arteries (patients were 5 times more likely to die after 2 years than those who received metal stents). Dr. Valentin Fuster, director of the Cardiovascular Institute at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York said stents are less commonly used in Europe, implanted in only about 15 % of patients there while drug-lined stents are used in up to 30% of Americans having heart attacks. The new research was presented by Dr. Gabriel Steg, of the Hospital Bichat-Claude Bernard in Paris, at a meeting of the European Society of Cardiology in Vienna. Dr. Eckhart Fleck, director of cardiology at the German Heart Institute in Berlin and a spokesman for the European Society of Cardiology said that "Drug-eluting stents are not for everyone." [4]

Urinary Tract[edit | edit source]

Ureteral stents are used to ensure the patency of a ureter, which may be compromised, for example, by a kidney stone. This method is sometimes used as a temporary measure, to prevent damage to a blocked kidney, until a procedure to remove the stone can be performed.

A urethral/prostatic stent might be needed if a man is unable to urinate. Often this situation occurs when an enlarged prostate pushes against the urethra, blocking the flow of urine. The placement of a stent can open the obstruction, avoiding the collapse of the urethra.

Stent Graft[edit | edit source]

A stent graft is a tubular device, which is composed of special fabric supported by a rigid structure, usually metal. The rigid structure is called a stent. An average stent on its own has no covering, and therefore is usually just a metal mesh. Although there are many types of stent, these stents are used mainly for vascular intervention.

The device is used primarily in Endovascular surgery. Stent grafts are used to support weak points in arteries, commonly known as an aneurysm. Stent grafts are most commonly used in the repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, in a procedure called an EVAR. The theory behind the procedure is that once in place inside the aorta, the stent graft acts as a false lumen for blood travel through, instead of into the aneurysm sack.

Other[edit | edit source]

- CHD Stent

- Rectal Stent

- Oesophageal Stent

- Biliary Stent

- Pancreatic Stent

2009 and 2007 Focused Update: ACC/AHA/SCAI Guidelines on Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (DO NOT EDIT)[5][6][edit | edit source]

Recommendations for the Use of Stents in STEMI (DO NOT EDIT)[5][edit | edit source]

| Class IIa |

| "1.It is reasonable to use a DES as an alternative to a BMS for primary PCI in STEMI.[7][8](Level of Evidence: B) " |

| Class IIa |

| "1. A DES may be considered for clinical and anatomic settings† in which the efficacy/safety profile appears favorable.[9][10][11][12](Level of Evidence: A) " |

Drug-Eluting and Bare-Metal Stents (DO NOT EDIT)[6][edit | edit source]

| Class I |

| "1. A DES should be considered as an alternative to a BMS in those patients for whom clinical trials indicate a favorable effectiveness/safety profile. (Level of Evidence: A) " |

| "2. Before implanting a DES, the interventional cardiologist should discuss with the patient the need for and duration of DAT and confirm the patient’s ability to comply with the recommended therapy for DES. (Level of Evidence: B) " |

| "2. In patients who are undergoing preparation for PCI and are likely to require invasive or surgical procedures for which DAT must be interrupted during the next 12 months, consideration should be given to implantation of a BMS or performance of balloon angioplasty with a provisional stent implantation instead of the routine use of a DES.(Level of Evidence: C) " |

| Class IIa |

| "1. In patients for whom the physician is concerned about risk of bleeding, a lower dose of 75 mg to 162 mg of aspirin is reasonable.(Level of Evidence: C) " |

| Class IIb |

| "1. A DES may be considered for clinical and anatomic settings in which the effectiveness/safety profile appears favorable but has not been fully confirmed by clinical trials. (Level of Evidence: C) " |

Related Chapters[edit | edit source]

External links[edit | edit source]

- Drug-Eluting Stents — Angioplasty.Org

- Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe

- How a Dentist's Name Became a Synonym for a Life-saving Device: The Story of Dr. Charles Stent Journal of the History of Dentistry/Vol. 49, No: 2, July 2001

- Cleveland Clinic Webchat - Interventional Procedures - Stents, Angioplasty and New Approaches to Treat Heart Disease with Dr. Samir Kapadia

- Cleveland Clinic Webchat - Interventional Procedures - Questions & Answers about Stents, Angioplasty and New Approaches to Treat Heart Disease with Dr. Stephen Ellis

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Lange RA, Hillis LD (2010). "Second-generation drug-eluting coronary stents". N Engl J Med. 362 (18): 1728–30. doi:10.1056/NEJMe1001069. PMID 20445185.

- ↑ Brophy JM, Belisle P, Joseph L (2003). "Evidence for use of coronary stents. A hierarchical bayesian meta-analysis". Ann Intern Med. 138 (10): 777–86. PMID 12755549.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT00114972 at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ Yahoo.com, International study shows stent risks

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, King SB, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Bailey SR, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Casey DE, Green LA, Hochman JS, Jacobs AK, Krumholz HM, Morrison DA, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Peterson ED, Sloan MA, Whitlow PL, Williams DO (2009). "2009 focused updates: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2004 guideline and 2007 focused update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines on percutaneous coronary intervention (updating the 2005 guideline and 2007 focused update) a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 54 (23): 2205–41. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.015. PMID 19942100. Retrieved 2011-12-06. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 "2007 Focused update of the ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions : Official Journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 71 (1): E1–40. 2008. doi:10.1002/ccd.21475. PMID 18080332. Retrieved 2012-11-07. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Valgimigli M, Campo G, Percoco G, et al. Comparison of angioplasty with infusion of tirofiban or abciximab and with implantation of sirolimus-eluting or uncoated stents for acute myocardial infarction: the MULTISTRATEGY randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1788 –99.

- ↑ Stone GW, Lansky AJ, Pocock SJ, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:1946 –59.

- ↑ Neumann FJ, Kastrati A, Pogatsa-Murray G, et al. Evaluation of prolonged antithrombotic pretreatment (‘cooling-off‘ strategy) before intervention in patients with unstable coronary syndromes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1593–9.

- ↑ Marroquin OC, Selzer F, Mulukutla SR, et al. A comparison of bare-metal and drug-eluting stents for off-label indications. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:342–52.

- ↑ Garg P, Normand SL, Silbaugh TS, et al. Drug-eluting or bare-metal stenting in patients with diabetes mellitus: results from the Massachusetts Data Analysis Center Registry. Circulation. 2008;118:2277– 85.

- ↑ Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cox DA, et al. A polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:221–31.

KSF

KSF