Tuberculosis pathophysiology

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 10 min

From Wikidoc - Reading time: 10 min

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yR51KVF4OX0%7C350}} |

|

Tuberculosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Drug-Susceptible and Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis(ATS 2025 Guidelines) |

|

Case Studies |

|

Tuberculosis pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Tuberculosis pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Tuberculosis pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Mashal Awais, M.D.[2], João André Alves Silva, M.D. [3]

Overview[edit | edit source]

Transmission of M. tuberculosis occurs when individuals with active pulmonary disease cough, speak, sneeze or sing expelling the infectious droplets. The mycobacterium tuberculosis favors the upper lung lobes due to the high oxygen level. Tuberculosis is a prototypical granulomatous infection. The granuloma surrounds the mycobacteria and prevents their dissemination and facilitates the immune cell interaction. Within the granuloma, CD4 T lymphocytes release chemokines that activate local macrophages and recruit other immune cells..

Pathogenesis[edit | edit source]

Transmission of M. tuberculosis occurs when individuals with active pulmonary disease cough, speak, sneeze or sing expelling the infectious droplets that can pass to the terminal bronchioles and alveoli then phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages where they can replicate in the endosomes of alveolar macrophages. As a part of the immune response by these macrophages, the alveolar macrophages release cytokines that recruits further macrophages, neutrophils, and monocytes, surrounding the bacilli. Despite having a very low infectious dose (ID<200 bacteria), 90% of the infected immunocompetent individuals are asymptomatic. In most cases, the bacteria may either be eliminated or enclosed within a granuloma. The granuloma is a structured, radial aggregation of macrophages, epithelioid cells, T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, and fibroblasts that prevents the spreading of mycobacteria and enhances interaction of the immune cells.[1] The primary site of infection in the lung is called the Ghon focus that is mainly located in either the upper part of the lower lobe, or the lower part of the upper lobe.[1][2]

Primary Infection[edit | edit source]

The infected macrophages are transported through the lymphatics to the regional lymph nodes in the immunocompetent individuals. However, with impaired immune response, these macrophages can pass through the bloodstream to enter any part of the body. Those foci of primary infection usually resolve without any consequences, but they can act as a foci of M. tuberculosis dissemination. There are particular organs that are more susceptible to bacterial replication as well as being potential metastatic foci which include:[1][2]

- Apical-posterior regions of the lungs

- Lymph nodes

- Kidneys

- Vertebral bodies

- Extremities of long bones

- Juxta ependymal meningeal regions

Although TB is a systemic disease and all organs can be affected, the heart, pancreas, skeletal muscles and thyroid are rarely involved.[3] In a few cases, when the infectious dose is high and antigens concentration in the primary focus is high, the immune response and hypersensitivity can lead to necrosis and calcification of this lesion, and these primary calcified foci are then called Ranke complex.[1][4]

Progression of the Primary Infection[edit | edit source]

Primary foci of infection can enter the large pulmonary lymph nodes. These may lead to:[1]

- Bronchial collapse

- atelectasis

- Bronchial erosion, with more dissemination of infection

- In non-caucasian children, elderly patients and HIV/AIDS, the immune response is impaired, consequently the primary focus of infection can deteriorate into progressive primary disease, with advancing pneumonia.

- In addition,the infection may result in cavity formation with transmission of the infection through the bronchi.[1][5][6]

- In young children, the onset of immune response may be delayed after the bacterial dissemination resulting in military tuberculosis. Bacteria can spread directly from the primary focus, or from the Weigart focus (metastatic focus adjacent to a pulmonary vein) through the blood.[1][7]

- In younger patients, rupture of subpleural foci into the pleural space may occur leading to serofibrinous pleurisy.[1] The most serious site of the M. tuberculosis dissemination is the postero-apical regions of the lung where it can replicate hidden from the immune system.[1]

Immunopathogenesis[edit | edit source]

There are two types of immune response against tuberculosis that include the innate and acquired immune responses. However, the cell-mediated immune response predominates over the humoral type.

Innate Immune Response[edit | edit source]

Initially, The immune response generated against M. tuberculosis is minimal, enabling it to replicate inside the alveolar macrophages forming the Ghon focus, or metastatic foci. Recognition and phagocytosis of the M. tuberculosis bacilli by the alveolar macrophages occurs through interaction with certain receptors that are located on the surface of macrophages:[8]

- Toll-like Receptor 2 (TLR2)

- TLR4

- TLR9

- Dectin-1

- DC-SIGN

- Mannose receptor

- Complement receptors

- NOD2

Acquired Immunity and Granuloma Formation[edit | edit source]

- The granuloma control the infection; however, it enables the mycobacterium to survive inside for a long time.

- It is important to maintain a balance between the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines released to decrease or control the mycobacterial proliferation.

- TNF-α and IFN-γ stimulate granuloma formation. On the other hand, IL-10 is one of the major negative regulators and inhibitors of granuloma formation.

- The granuloma is structured by blood-derived macrophages (derived from monocytes), epithelioid cells (differentiated macrophages), and multinucleated giant cells (also known as Langhans giant cells), surrounded by T lymphocytes.

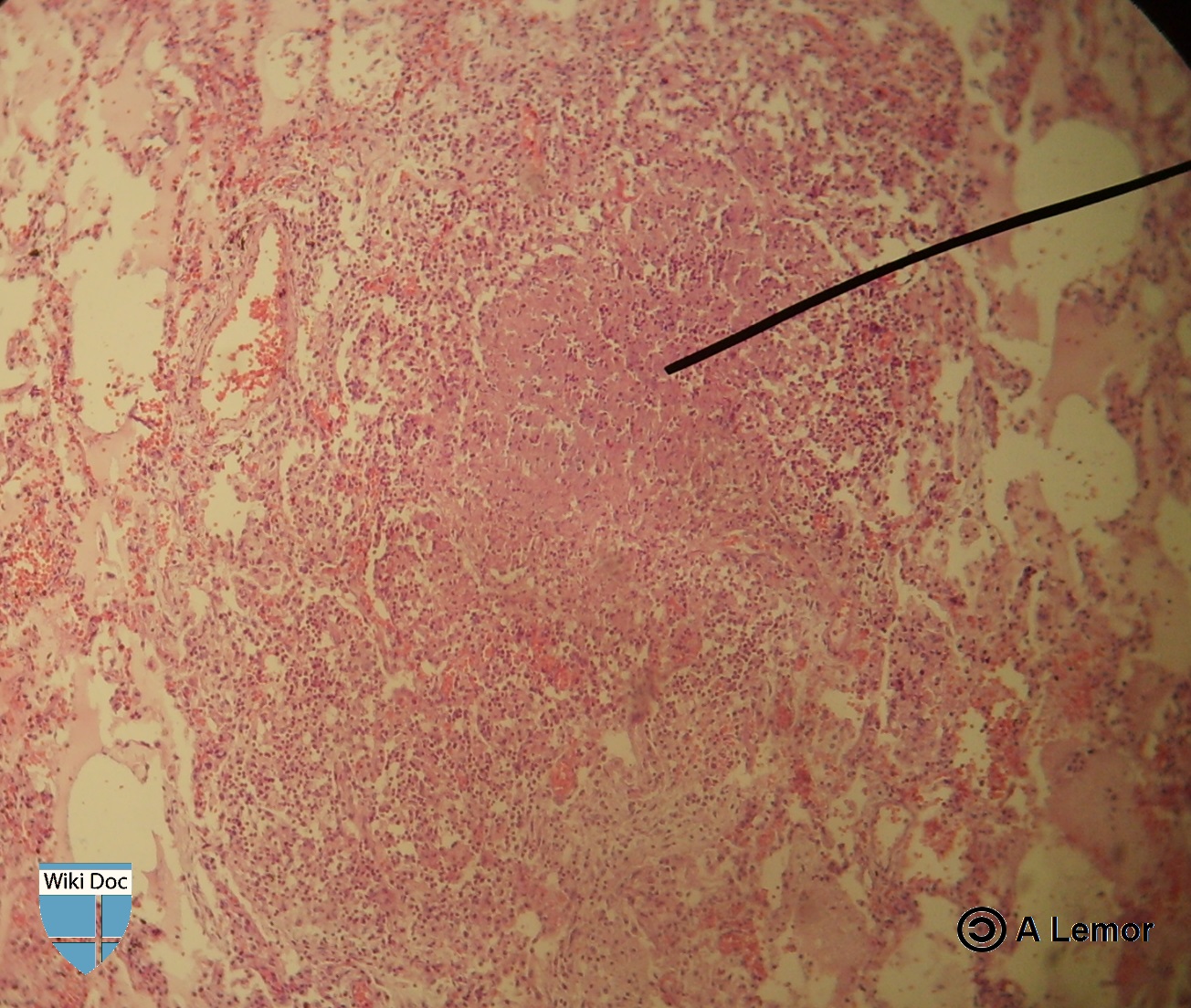

- Caseous granulomas are the main characteristic of tuberculosis. The caseous granulomas include epithelioid macrophages and some lymphocytes with a necrotic center. Other types of granuloma include non-necrotizing granulomas, that are mainly formed of macrophages and a few lymphocytes, necrotic neutrophilic granulomas, and completely fibrotic granulomas.[9]

- Several chemokines are involved in granuloma formation released either from the respiratory tract epithelium or the immune cells themselves.

- Interaction with CCR2 receptor with (CCL2/MCP-1, CCL12, and CCL13) is necessary for the initial recruitment of macrophages.

- Macrophages and lymphocytes release a chemokine called osteopontin that enhances the adhesion and recruitment of the immune cells.

- CCL19 and CCL21 are important for recruitment of IFN--producing T cells.

- In TNF-deficient mice, absence of these chemokines as a result of inhibition of the expression of the CC and CXC chemokines prevents the recruitment of other macrophages and T lymphocytes. This finding sheds the light on the role of TNF in granuloma formation.[9]

Molecular Pathogenesis[edit | edit source]

- The mycobacterial antigens are presented on thee surfaces of alveolar macrophages and dendritic cells through class II major histocompatibility complex. These antigens are recognized by CD4 lymphocytes through αβ T-cell receptors. Following that, CD4 lymphocytes release chemokines that recruit more macrophages to the foci of infection.

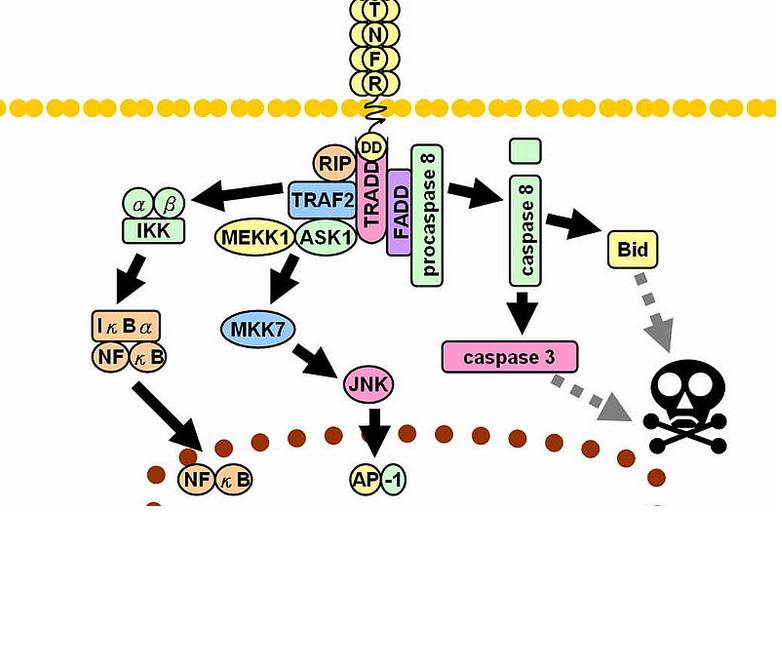

- Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) signaling activates additional macrophages. [10]

- Metalloproteinase converts the transmembrane protein to soluble TNF-α which interacts with the TNFR1 and TNFR2 receptors inducing apoptosis through caspase-dependent pathways

- TNF along side the synergistic action of interferon-gamma enhances the phagocytic activity of the macrophages and facilitates the intracellular killing of mycobacteria by reactive nitrogen and oxygen intermediates.

- Neutralization of the TNF-α activity leads to the mycobacteria survival within the granuloma in latent infection.

- TNF activates release of CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CCL8 chemokines and increases CD54 leading to accumulation of immune cells and it is the main element in the process of granuloma formation and maintenance. [10]

- The immune cells release large amounts of lytic enzymes leading to tissue necrosis.

Once within alveolar macrophages, M. tuberculosis uses multiple mechanisms in order to survive:[1]

- Urease - prevents acidification of macrophageal lysosomes, limiting action of cellular enzymes

- Secretion of antioxidants, for suppression of reactive oxygen species, such as:

Transmission[edit | edit source]

After contact with a patient having the active TB, and inhalation of the M. tuberculosis, the risk of developing active tuberculosis is low with a life-time risk of about 10%.[12] The probability of transmission between individuals depends on the number of expelled infectious droplets the ventilation, the duration of the exposure, immunity, and the virulence of the M. tuberculosis strain.[13] The probability of transmitting the infection is highest during the first years of getting the infection. After that, it decreases.[14]

In rare occasions, the mycobacteria can be transmitted by other ways apart from the respiratory route in which, the formation of foci in the regional lymph nodes frequently occurs. Those routes include:[1]

Associated Conditions[edit | edit source]

AIDS[edit | edit source]

- Tuberculosis influence the progression of HIV replication leading to an increase in in the mortality rate.[15]

- HIV infected patients, particularly those having low CD4 lymphocytes counts, are more likely to develop reactivation of latent tuberculosis. Moreover, when an individual has been recently infected with M. tuberculosis, they progress rapidly into active disease.[1][16][17] The correlation between AIDS and the risk of TB infection is still not fully understood.[1]

Patients with AIDS are more prone to get pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Extrapulmonary disease in AIDS patients has characteristic manifestations, such as:[1]

- Higher risk of progression into disseminated disease[18]

- DIC and acute respiratory failure

- Tuberculous pleuritis occurs bilaterally

- Abdominal and mediastinal lymphadenopathy frequently occurs

- Higher risk of Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS)[19]

- Common abscesses of:[1]

Gallery[edit | edit source]

-

Left lateral margin of a tongue of a tuberculosis patient, which had been retracted in order to reveal the lesion that had been caused by the Gram-positive bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosisAdapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]

-

Light photomicrograph revealing some of the histopathologic cytoarchitectural characteristics seen in a mycobacterial skin infection.[ http://phil.cdc.gov/phil/ Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.][20]

-

Light photomicrograph revealing some of the histopathologic cytoarchitectural characteristics seen in a mycobacterial skin infection Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]

-

Light photomicrograph revealing some of the histopathologic cytoarchitectural characteristics seen in a mycobacterial skin infection Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]

-

Light photomicrograph revealing some of the histopathologic cytoarchitectural characteristics seen in a mycobacterial skin infection Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]

-

Light photomicrograph revealing some of the histopathologic cytoarchitectural characteristics seen in a mycobacterial skin infection Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]

-

Photomicrograph describing tuberculosis of the placenta.Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]

-

Histopathology of tuberculosis, endometrium. Ziehl-Neelsen stain.Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]

-

Histopathology of tuberculosis, placenta.Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]

-

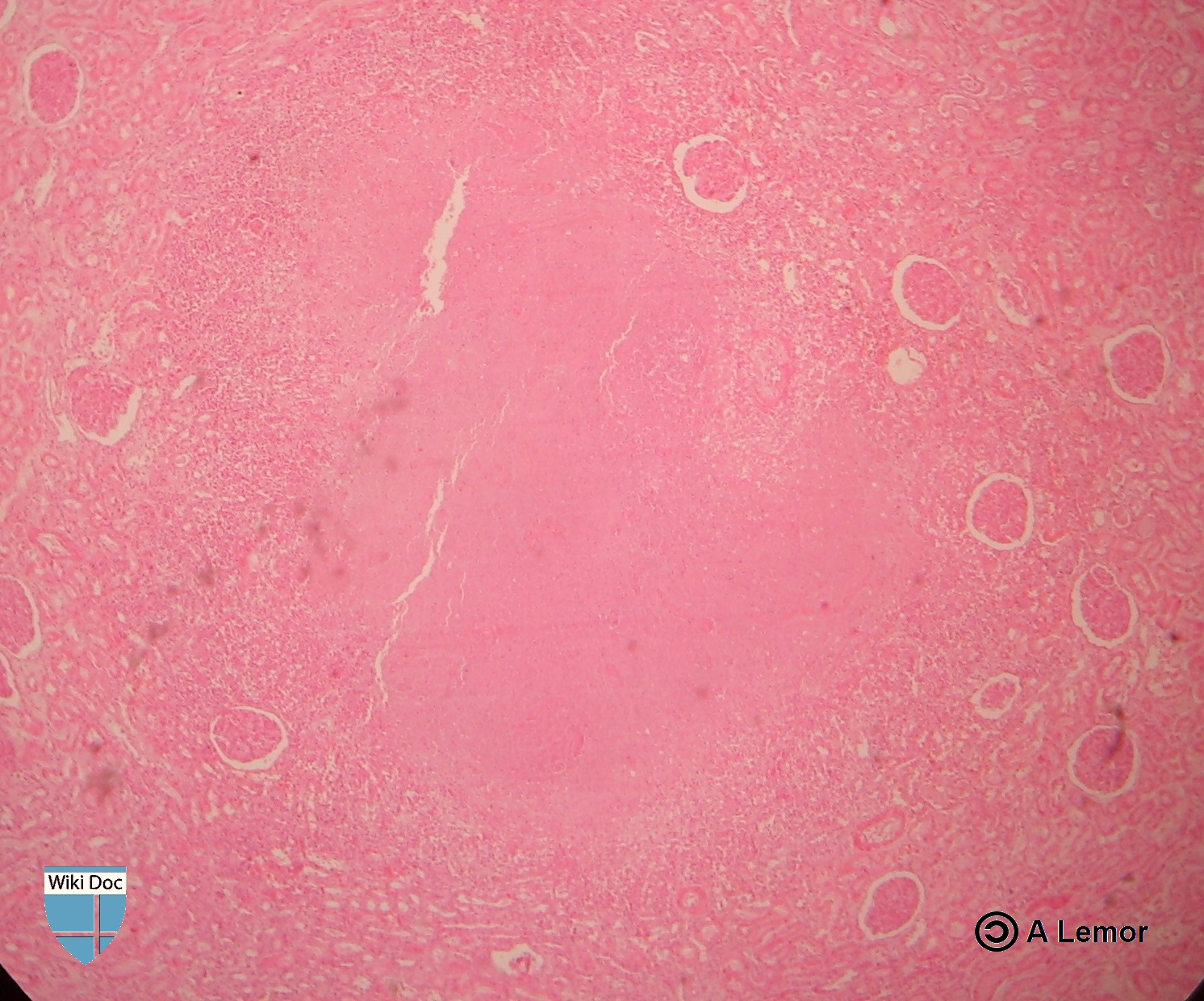

Miliar Tuberculosis

-

Renal Tuberculosis lesion

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Mandell, Gerald (2010). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 0443068399.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Herrmann J, Lagrange P (2005). "Dendritic cells and Mycobacterium tuberculosis: which is the Trojan horse?". Pathol Biol (Paris). 53 (1): 35–40. PMID 15620608.

- ↑ Agarwal R, Malhotra P, Awasthi A, Kakkar N, Gupta D (2005). "Tuberculous dilated cardiomyopathy: an under-recognized entity?". BMC Infect Dis. 5 (1): 29. PMID 15857515.

- ↑ Grosset J (2003). "Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the extracellular compartment: an underestimated adversary". Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 47 (3): 833–6. PMID 12604509.

- ↑ Stead WW, Lofgren JP, Warren E, Thomas C (1985). "Tuberculosis as an endemic and nosocomial infection among the elderly in nursing homes". N Engl J Med. 312 (23): 1483–7. doi:10.1056/NEJM198506063122304. PMID 3990748.

- ↑ Murray JF (1990). "Cursed duet: HIV infection and tuberculosis". Respiration. 57 (3): 210–20. PMID 2274719.

- ↑ Kim J, Park Y, Kim Y, Kang S, Shin J, Park I, Choi B (2003). "Miliary tuberculosis and acute respiratory distress syndrome". Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 7 (4): 359–64. PMID 12733492.

- ↑ Aderem A, Underhill DM (1999). "Mechanisms of phagocytosis in macrophages". Annu Rev Immunol. 17: 593–623. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.593. PMID 10358769.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Silva Miranda M, Breiman A, Allain S, Deknuydt F, Altare F (2012). "The tuberculous granuloma: an unsuccessful host defense mechanism providing a safe shelter for the bacteria?". Clin Dev Immunol. 2012: 139127. doi:10.1155/2012/139127. PMC 3395138. PMID 22811737.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha".

- ↑ "TNF Alpha". Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ↑ Glaziou P, Falzon D, Floyd K, Raviglione M (2013). "Global epidemiology of tuberculosis". Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 34 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1333467. PMID 23460002.

- ↑ "Causes of Tuberculosis". Mayo Clinic. 2006-12-21. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ↑ Lawn SD, Zumla AI (2011). "Tuberculosis". Lancet. 378 (9785): 57–72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62173-3. PMID 21420161.

- ↑ Zumla A, Raviglione M, Hafner R, von Reyn CF (2013). "Tuberculosis". N Engl J Med. 368 (8): 745–55. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1200894. PMID 23425167.

- ↑ Daley CL, Small PM, Schecter GF, Schoolnik GK, McAdam RA, Jacobs WR; et al. (1992). "An outbreak of tuberculosis with accelerated progression among persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. An analysis using restriction-fragment-length polymorphisms". N Engl J Med. 326 (4): 231–5. doi:10.1056/NEJM199201233260404. PMID 1345800.

- ↑ Bouvet E, Casalino E, Mendoza-Sassi G, Lariven S, Vallée E, Pernet M; et al. (1993). "A nosocomial outbreak of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium bovis among HIV-infected patients. A case-control study". AIDS. 7 (11): 1453–60. PMID 8280411.

- ↑ Shafer RW, Kim DS, Weiss JP, Quale JM (1991). "Extrapulmonary tuberculosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection". Medicine (Baltimore). 70 (6): 384–97. PMID 1956280.

- ↑ Meintjes G, Lawn SD, Scano F, Maartens G, French MA, Worodria W; et al. (2008). "Tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: case definitions for use in resource-limited settings". Lancet Infect Dis. 8 (8): 516–23. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70184-1. PMC 2804035. PMID 18652998.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 20.7 20.8 "Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention".

KSF

KSF![Left lateral margin of a tongue of a tuberculosis patient, which had been retracted in order to reveal the lesion that had been caused by the Gram-positive bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosisAdapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]](https://www.wikidoc.org/images/0/09/TB1.jpg)

![Light photomicrograph revealing some of the histopathologic cytoarchitectural characteristics seen in a mycobacterial skin infection.[ http://phil.cdc.gov/phil/ Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.][20]](https://www.wikidoc.org/images/e/ed/TB2.jpg)

![Light photomicrograph revealing some of the histopathologic cytoarchitectural characteristics seen in a mycobacterial skin infection Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]](https://www.wikidoc.org/images/7/79/Leprosy-35.jpg)

![Light photomicrograph revealing some of the histopathologic cytoarchitectural characteristics seen in a mycobacterial skin infection Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]](https://www.wikidoc.org/images/6/60/Leprosy-36.jpg)

![Light photomicrograph revealing some of the histopathologic cytoarchitectural characteristics seen in a mycobacterial skin infection Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]](https://www.wikidoc.org/images/9/93/Leprosy-37.jpg)

![Light photomicrograph revealing some of the histopathologic cytoarchitectural characteristics seen in a mycobacterial skin infection Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]](https://www.wikidoc.org/images/b/b5/Leprosy-38.jpg)

![Photomicrograph describing tuberculosis of the placenta.Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]](https://www.wikidoc.org/images/b/be/TB3.jpg)

![Histopathology of tuberculosis, endometrium. Ziehl-Neelsen stain.Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]](https://www.wikidoc.org/images/d/dd/TB4.jpg)

![Histopathology of tuberculosis, placenta.Adapted from Public Health Image Library (PHIL), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[20]](https://www.wikidoc.org/images/9/97/TB5.jpg)