1890 United States census

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

| 1890 United States census | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Seal of the Department of the Interior | ||

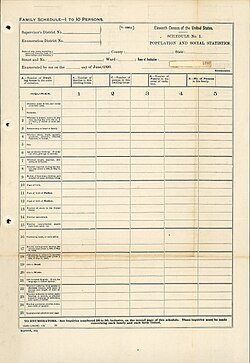

1890 census form | ||

| General information | ||

| Country | United States | |

| Authority | Census Office | |

| Results | ||

| Total population | 62,979,766 ( | |

| Most populous | New York 6,003,174 | |

| Least populous | Nevada 47,335 | |

The 1890 United States census was taken beginning June 2, 1890. The census determined the resident population of the United States to be 62,979,766, an increase of 25.5 percent over the 50,189,209 persons enumerated during the 1880 census. The data reported that the distribution of the population had resulted in the disappearance of the American frontier.

This was the first census in which a majority of states recorded populations of over one million and the first in which three cities, New York City, Chicago, and Philadelphia, recorded populations of over one million. The census also saw Chicago rise in rank to the nation's second-most populous city, a position it would hold until Los Angeles, the 57th-most populous city as of 1890, supplanted it in 1990. This was the first U.S. census to use machines to tabulate the collected data.

Most of the 1890 census materials were destroyed on January 10, 1921, when the Commerce Department building caught fire, and in the subsequent disposal of the remaining damaged records.

Census questions

[edit]The 1890 census collected the following information:[1]

- address

- number of families in house

- number of persons in house

- names

- whether a soldier, sailor or marine (Union or Confederate) during the American Civil War, or a widow of such person

- relationship to head of family

- race, described as white, black, mulatto, quadroon, octoroon, Chinese, Japanese, or Indian

- sex

- age

- marital status

- married within the year

- mother of how many children, and number now living

- place of birth of person, and their father and mother

- if foreign-born, number of years in U.S.

- whether naturalized

- whether naturalization papers have been taken out

- profession, trade or occupation

- months unemployed during census year

- ability to read and write

- ability to speak English, and, if unable, language or dialect spoken

- whether suffering from acute or chronic disease, with name of disease and length of time afflicted

- whether defective in mind, sight, hearing or speech, or whether crippled, maimed or deformed, with name of defect

- whether a prisoner, convict, homeless child, or pauper

- home rented, or owned by head or member of family, and, if owned, whether free from mortgage

- if farmer, whether farm is rented, or owned by head or member of family; if owned, whether free from mortgage; if rented, post office box of owner

Methodology

[edit]

The 1890 census was the first to be compiled using methods invented by Herman Hollerith and was overseen by Superintendents Robert P. Porter (1889–1893) and Carroll D. Wright (1893–1897). Data was entered on a machine readable medium (punched cards) and tabulated by machine.[2] Changes from the 1880 census included the larger population, the number of data items to be collected from individuals, the Census Bureau headcount, the volume of scheduled publications, and the use of Hollerith's electromechanical tabulators. The net effect of these changes was to reduce the time required to process the census from eight years for the 1880 census to six years for the 1890 census.[3] The total population of 62,947,714, the family, or rough, count, was announced after only six weeks of processing (punched cards were not used for this tabulation).[4][2]: 61 The public reaction to this tabulation was disbelief, as it was widely believed that the "right answer" was at least 75,000,000.[5]

Significant findings

[edit]The United States census of 1890 showed a total of 248,253 Native Americans living in the United States, down from 400,764 Native Americans identified in the census of 1850.[6]

The 1890 census announced that the frontier region of the United States no longer existed,[7] and that the Census Bureau would no longer track the westward migration of the U.S. population.

By 1890, settlement in the American West had reached sufficient population density that the frontier line had disappeared. For the 1890 census, the Census Bureau released a bulletin declaring the closing of the frontier, stating: "Up to and including 1880 the country had a frontier of settlement, but at present the unsettled area has been so broken into by isolated bodies of settlement that there can hardly be said to be a frontier line. In the discussion of its extent, its westward movement, etc., it can not, therefore, any longer have a place in the census reports."[8]

Statisticians at the time argued that the results of the 1890 census was most likely an undercount of the total population in the United States from anywhere between one million to several millions, and that African Americans, working-class people, and young children were most likely to be undercounted.[9]

Data availability

[edit]

The original data for the 1890 census is mostly unavailable. The population schedules were damaged in a fire in the basement of the U.S. Department of Commerce building in Washington, D.C. in 1921. Some 25% of the materials were presumed destroyed and another 50% damaged by smoke and water, although the actual damage may have been closer to 15–25%. The damage to the records led to an outcry for a permanent National Archives.[10][11] In December 1932, following standard federal record-keeping procedures, the Chief Clerk of the Bureau of the Census sent the Librarian of Congress a list of papers to be destroyed, including the original 1890 census schedules. The Librarian was asked by the Bureau to identify any records which should be retained for historical purposes, but the Librarian did not accept the census records. Congress authorized destruction of that list of records on February 21, 1933, and the surviving original 1890 census records were destroyed by government order by 1934 or 1935. Few sets of microdata from the 1890 census survive.[12] Aggregate data for small areas, together with compatible cartographic boundary files, can be downloaded from the National Historical Geographic Information System.

State rankings

[edit]| Rank | State | Population |

|---|---|---|

| 01 | 6,003,174 | |

| 02 | 5,258,113 | |

| 03 | 3,826,352 | |

| 04 | 3,672,329 | |

| 05 | 2,679,185 | |

| 06 | 2,238,947 | |

| 07 | 2,235,527 | |

| 08 | 2,192,404 | |

| 09 | 2,093,890 | |

| 10 | 1,912,297 | |

| 11 | 1,858,635 | |

| 12 | 1,837,353 | |

| 13 | 1,767,518 | |

| 14 | 1,693,330 | |

| 15 | 1,655,980 | |

| 16 | 1,617,949 | |

| 17 | 1,513,401 | |

| 18 | 1,444,933 | |

| 19 | 1,428,108 | |

| 20 | 1,310,283 | |

| 21 | 1,289,600 | |

| 22 | 1,213,398 | |

| 23 | 1,151,149 | |

| 24 | 1,128,211 | |

| 25 | 1,118,588 | |

| 26 | 1,062,656 | |

| 27 | 1,042,390 | |

| 28 | 762,794 | |

| 29 | 746,258 | |

| 30 | 661,086 | |

| 31 | 413,249 | |

| 32 | 391,422 | |

| 33 | 376,530 | |

| 34 | 357,232 | |

| 35 | 348,600 | |

| 36 | 345,506 | |

| 37 | 332,422 | |

| 38 | 317,704 | |

| X | 258,657 | |

| X | 230,392 | |

| X | 210,779 | |

| 39 | 190,983 | |

| 40 | 168,493 | |

| X | 160,282 | |

| 41 | 142,924 | |

| 42 | 88,548 | |

| X | 88,243 | |

| 43 | 62,555 | |

| 44 | 47,355 | |

| X | 32,052 |

City rankings

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Library Bibliography Bulletin 88, New York State Census Records, 1790–1925". New York State Library. October 1981. p. 44 (p. 50 of PDF). Archived from the original on January 30, 2009. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ^ a b c Truesdell, Leon E. (1965). The Development of Punch Card Tabulation in the Bureau of the Census: 1890–1940. US GPO.

- ^ Report of the Commissioner of Labor In Charge of The Eleventh Census to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1895. Washington, DC: United States Government Publishing Office. July 29, 1895. hdl:2027/osu.32435067619882. OCLC 867910652. p. 9: "You may confidently look for the rapid reduction of the force of this office after the 1st of October, and the entire cessation of clerical work during the present calendar year. ... The condition of the work of the Census Division and the condition of the final reports show clearly that the work of the Eleventh Census will be completed at least two years earlier than was the work of the Tenth Census." — Carroll D. Wright, Commissioner of Labor in Charge

- ^ "Population and Area (Historical Censuses)" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 24, 2008. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ^ Austrian, Geoffrey D. (1982). Herman Hollerith: Forgotten Giant of Information Processing. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 85–86. ISBN 0-231-05146-8.

- ^ Dippie, Brian W. (1982). The Vanishing American: White Attitudes and U.S. Indian Policy. Middleton, CT: Wesleyan University Press. p. ??. ISBN 0-8195-5056-6. The data yielded by this census provided strong evidence that the United States' policies towards Native Americans had had a significant impact on the enumeration of the census in the second half of the 19th century. US domestic policy combined with wars, genocide, famine, disease, a declining birthrate, and exogamy (with the children of biracial families declaring themselves to be white rather than Indian) accounted for the decrease in the enumeration of the census. Chalk, Frank; Jonassohn, Kurt (1990). The History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04446-1.

- ^ Porter, Robert; Gannett, Henry; Hunt, William (1895). "Progress of the Nation", in "Report on Population of the United States at the Eleventh Census: 1890, Part 1". Bureau of the Census. pp. xviii–xxxiv.

- ^ Turner, Frederick Jackson (1920). "The Significance of the Frontier in American History". The Frontier in American History. p. 1.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1894). "Was the Count of Population in 1890 Reasonably Correct?". Publications of the American Statistical Association. 4 (28/29): 99–102. doi:10.2307/2276233. ISSN 1522-5437. JSTOR 2276233.

- ^ Blake, Kellee (Spring 1996). "First in the Path of the Firemen: The Fate of the 1890 Population Census, Part 1". Prologue Magazine. 28 (1). Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration. ISSN 0033-1031. OCLC 321015582. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ Blake, Kellee (Spring 1996). "First in the Path of the Firemen: The Fate of the 1890 Population Census, Part 3". Prologue Magazine. 28 (1). Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration. ISSN 0033-1031. OCLC 321015582. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ "Availability of 1890 Census – History". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- ^ Including Indian Territory, which was yet to be combined with Oklahoma Territory to form the state of Oklahoma.

- ^ The District of Columbia is not a state but was created with the passage of the Residence Act of 1790.

- ^ Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in the United States: 1790 to 1990, U.S. Census Bureau, 1998

- ^ "Regions and Divisions". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

External links

[edit]- Mayo-Smith, Richmond (1891), "The Eleventh Census of the United States". In: The Economic Journal (EJ), Vol. 1, pp. 43–58 (in

Wikisource)

Wikisource) - Walker, Francis A. (1888). "The Eleventh Census of the United States". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2 (2): 135–161.

- 1891 U.S Census Report Contains 1890 census results

- Historical US Census data from the U.S. Census Bureau website

- Hollerith 1890 Census Tabulator by Columbia University

- "The Fate of the 1890 Population Census" from the National Archives website

KSF

KSF