1899 United States Senate election in Pennsylvania

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 19 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 19 min

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Statistics for the 79th and final vote, April 19, 1899 124 votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

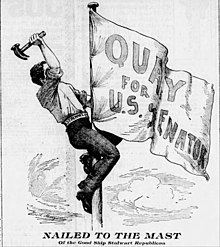

An election for the United States Senate was held by the Pennsylvania General Assembly beginning on January 17, 1899, to fill the seat then held by Matthew Quay for a six-year term beginning March 4, 1899. Quay was a candidate for re-election, but he was damaged by a pending indictment for involvement in financial irregularities with state money; his trial took place during the three months that the legislature attempted to resolve the Senate deadlock, and he was acquitted the day it adjourned, having failed to elect a senator. Quay was appointed to the Senate seat by the governor, but the Senate refused to seat him on the grounds that the governor lacked the constitutional authority to make the selection, and the seat remained vacant until the next meeting of the legislature, in 1901, when Quay was elected.

Quay was Pennsylvania's Republican political boss, and had served two terms in the Senate. Dissident Republicans and reformers were determined to defeat him for a third term, and sought to elect candidates in the 1898 elections for the legislature. Prominent among the anti-Quay forces was Philadelphia businessman John Wanamaker, who had been defeated for the Republican nominations for senator in 1897 and governor in 1898 through Quay's influence. Wanamaker made speeches against Quay during the 1898 campaign, though he refused to seek the Senate seat himself.

Although Republicans had an ample majority in the legislature, enough were opposed to Quay to deny the senator the majority he needed for re-election. Democrats and anti-Quay Republicans refused to join together to elect another candidate, though they had a majority between them. Democrats supported their 1898 gubernatorial candidate, George A. Jenks, while the dissident Republicans voted for several candidates before settling on Benjamin F. Jones. The legislature voted once a day during the session of over three months; no compromise was reached, and the session ended on April 20 without the election of a senator.

After the session and Quay's acquittal, Governor William A. Stone appointed Quay to the vacancy, but the U.S. Senate refused to seat him by one vote, and the senatorship remained vacant until 1901. Quay blamed his fellow Republican political boss, Mark Hanna of Ohio, for the defeat in the Senate, and gained revenge at the 1900 Republican National Convention by supporting Thomas C. Platt's scheme to politically sideline Governor Theodore Roosevelt of New York by making him vice president, over Hanna's strong objection. After Quay's return to the Senate in 1901, he served there until his death in 1904, when control of Quay's political machine passed to his fellow Pennsylvania senator, Boies Penrose.

Background

[edit]| Elections in Pennsylvania |

|---|

|

|

|

In drafting the Constitution, the members of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 agreed that United States Senators would be chosen by state legislatures, not by the people.[1] Federal law prescribed that the senatorial election was to take place beginning on the second Tuesday after the two houses of the legislature which would be in office when the senatorial term expired, convened and chose legislative officers. On the designated day, balloting for senator would take place in each of the two chambers of the legislature. If a majority of each house voted for the same candidate, then at the joint assembly held the following day at noon, the candidate would be declared elected. Otherwise, there would be a roll-call vote of all legislators, with a majority of those present needed to elect. In the event that no senator was elected, the legislature was required to hold at least one vote in joint assembly each day until it ended the session or a senator was elected.[2] If a vacancy occurred when the legislature was not in session, the governor could make a temporary appointment to serve until lawmakers convened.[3] This system was prone to deadlock if legislators could not agree. In the 1890s and 1900s, eight states failed to fill Senate seats for periods ranging from 10 months to four years; from 1901 to 1903, Delaware went unrepresented in the Senate.[4]

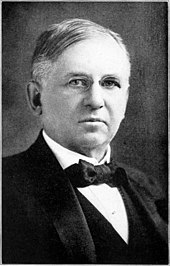

Matthew Quay was born September 30, 1833, in Dillsburg, Pennsylvania. After completing his education, he became a lawyer in 1854, practicing in Beaver, Pennsylvania, and became prothonotary of Beaver County in 1856. He served as an officer in the Union Army,[5] and was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions at the 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg. Quay was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, taking office in 1865,[5] and became part of the political machine of U.S. Senator Simon Cameron.[6] Beginning in 1872, Quay served as Cameron's lieutenant.[7] By the mid-1880s, Quay had seized control of the state Republican Party from Cameron's son, Senator Don Cameron,[8] and in 1887 was himself elected to the Senate, with re-election in 1893.[5] Money and patronage were Quay's weapons in gaining and maintaining power; he freely raided the state treasury, dispensing loans to those he favored and using state money to buy votes or the opinions of newspapers. He recognized the importance of this resource, himself serving as Pennsylvania State Treasurer from 1885 to 1887, and once said, "I don't mind losing the governorship or a legislature now and then, but I always need the state treasuryship."[5][9]

Opposition to Quay and indictment

[edit]

There had, since 1882, always been some opposition to Quay within the Pennsylvania Republican Party, but it had always been beaten.[10] Pennsylvania's senior senator, Don Cameron, announced he would retire at the end of his term in 1897. Philadelphia businessman and former United States Postmaster General John Wanamaker wanted the seat, which would be filled by the General Assembly in early 1897. Since most Republican legislators were beholden to Quay, his choice of nominee was usually accepted by the Republican legislative caucus, and Quay supported Boies Penrose. Wanamaker entered the race anyway, making speeches demonizing Quay, and making alliances with reformers in the legislature. Nevertheless, Penrose easily won the vote in the Republican legislative caucus in early 1897, and was elected.[11] Wanamaker continued his anti-Quay campaigning through his effort to gain the Republican nomination for governor in early 1898, and even though he failed, continued to give speeches against the senator, hoping to generate enough opposition to prevent his re-election by the legislature in early 1899.[12] His speeches brought the issue of bossism home to the voters of Pennsylvania, and helped elect Democrats or anti-Quay Republicans.[10]

On October 3, 1898, Quay was arrested for conspiracy to defraud the People's Bank of Philadelphia. Quay had arranged in 1896 for $1,000,000 of state funds (equivalent to $36,624,000 in 2023) to be deposited in it and had persuaded John S. Hopkins, cashier and manager of the bank, that the funds be invested in the Metropolitan Traction Company of New York, sending a telegram: "If you buy and carry a thousand Met for me I will shake the plum tree", believed by investigators to mean that funds from the state treasury would be used to cover the speculation.[13][14] The stock collapsed, the bank failed, and Hopkins fatally shot himself.[10][15] It was alleged that the bank was paying the interest on state funds not to the state treasury, but to Quay.[16] The information had been available for months; according to Quay biographer James Kehl, the indictment was timed to have had the greatest effect on the upcoming elections.[13] In spite of the allegations, Quay's hand-picked gubernatorial candidate, William A. Stone, was victorious by over 110,000 votes.[17]

Also indicted was Quay's son Richard and state treasurer Benjamin Haywood, though Richard Quay's indictment was withdrawn and Haywood would die before the verdict.[17] The anti-Quay political forces did their best to capitalize on the claims of corruption against Quay and his associates, attempting to deny him re-election while appearing to remain loyal Republicans in the public eye.[18] The trial was repeatedly delayed in late 1898, leading Quay to appeal to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania to get a judge assigned, wanting the matter disposed of before the legislative balloting for Senate began in January.[19] Instead a trial was set for late February.[20]

Caucus and early balloting

[edit]

The legislature that was to convene in January 1899 consisted of 164 Republicans, 84 Democrats and 6 Fusionists,[21] the last being elected across party lines by an anti-Quay coalition.[22] On January 3, 1899, the Republican legislators convened in caucus to choose a candidate for senator. Under the conventions of the time, anyone who attended would be bound by the outcome, and only 109 Republicans showed up, of whom 98 voted for Quay, an outcome which was made unanimous. Since there were 254 legislators in full, Quay needed 128 votes in the joint assembly to be elected, and even if the dissenting attendees could be counted in, he was 19 votes short of election. Nevertheless, his supporters cited the outcome as a triumph, and predicted the senator would easily pick up the remaining necessary votes.[23] The Democrats refused to join with the dissident Republicans to elect a senator, but decided on former congressman George A. Jenks, who had been their nominee for governor the previous year, as their candidate for Senate, while the Republicans who refused to support Quay initially had no single candidate, as Wanamaker had refused to run.[24] Confident of re-election, Quay made $40,000 (equivalent to $1,464,960 in 2023) available to bribe wavering legislators into supporting him.[17]

The initial voting in the two houses of the legislature took place in the state capital of Harrisburg on January 17. Quay received 27 votes in the Senate and 85 in the House, for a total of 112. Since there were a number of absentees and vacancies, 124 votes would be needed for election in the joint assembly, which put Quay 12 votes short. The Democratic candidate, Jenks, received 12 votes in the Senate and 70 in the House, and the leading other contender was John Dalzell, a Republican congressman from Pittsburgh, with 16 votes. This gave Quay a majority in the Senate but not in the House, necessitating balloting in joint assembly.[25]

By the rules of the joint assembly, there was to be one vote each day unless legislators decided otherwise.[26] Quay received a plurality on almost each vote, and sometimes a majority, but only on days a quorum was not present.[27] Congressman Joseph C. Sibley, a Democrat, was working for Quay and urged the Pennsylvania Democratic legislators to vote for Quay. Instead, the Democrats continued to support Jenks.[28] On February 27, the prosecution in the criminal case against Quay asked for more time; the matter was postponed until April as the senator's supporters claimed the case had collapsed.[29] On March 3, angered when John R. Farr, Speaker of the state House of Representatives, adjourned that body in a manner the Democrats and dissident Republicans considered arbitrary, they remained on the floor and announced they would elect their own Speaker, but they did not have enough for a quorum, and after the effort was denounced by a former Democratic Speaker, it collapsed.[30] That night, Quay's term in the Senate expired, and the seat became vacant; only Penrose represented Pennsylvania in the upper house.[5][31]

Later voting and deadlock

[edit]

On March 15, The New York Times reported that the deadlock was likely to persist to the end of the session, and that the Pennsylvania Senate seat would likely go unfilled when Congress next convened in December, even by a gubernatorial appointee, as the Senate had usually rejected attempts to fill a seat by appointment when a state legislature had failed to choose.[32] The balloting continued, once per day excepting Sundays, with Quay never getting close to a majority with a quorum.[27] The anti-Quay Republicans offered to meet with his supporters, but Quay's manager, state senator John C. Grady, was slow to accept, and it was clear the Quay Republicans would rather have deadlock than find a compromise candidate. This was along the lines that Quay urged in a letter to his supporters, "To temporize with those persons who for three months have prevented the election of a Senator in Pennsylvania would extricate them from the abyss into which they have plunged. Instead of making their treason to the party odious, their treason would be made respectable, and treason made respectable would become fashionable."[33] The Democrats refused to reach across the aisle to the anti-Quay Republicans to elect a compromise candidate, remaining loyal to Jenks.[34]

According to historian James A. Kehl:

The deliberations of the legislature tried men's patience and tired their minds. To those directly involved, the frantic efforts to make successful combinations or convert individual legislators turned the protracted struggle into a reign of terror—physically, mentally and morally. The tension was heightened by Quay's success in having his case brought to trial in Philadelphia ... The prosecution obviously had a weak case that had been patched together primarily to discredit Quay in political circles. He may have been guilty, but [Philadelphia district attorney Peter F.] Rothermel had neither the documents nor the witnesses to prove it.[19]

On April 17, Quay lost some support when Pittsburgh political boss and state senator Christopher Magee informed the Quay caucus he would no longer support the ex-senator. Magee and others attended a meeting of perhaps 15 to 20 legislators the following morning in the state senate's chamber. At the meeting they passed a resolution stating that Quay could not be elected, and Magee nominated Benjamin F. Jones, former chairman of the Republican National Committee, for senator. When the joint assembly convened, Jones received 69 votes to 85 for Jenks and 93 for Quay. It had been speculated that Magee could take at least 20 votes with him, but in the end only 14 legislators defected.[35] The final vote, on April 19, saw the same tally as the day before.[27] On the final ballot, four legislators were paired and state senator Alexander L. Hawkins was absent, as he was serving with his regiment in the Philippines.[36] The dissidents had hoped the Democrats would join with them to elect Jones, but they refused.[37] The following day, the legislature formally adjourned, leaving the Senate seat empty, and in a Philadelphia courtroom, Quay was acquitted of the charges.[17] To commemorate the acquittal, many Quay supporters planted plum trees; one in Gettysburg planted 50 and invited Quay to visit in a few years and shake all of them.[38]

Appointment

[edit]

On April 21, Governor Stone appointed Quay to fill the vacancy in the Senate.[39] There had been speculation he might do that, or call a special session of the legislature; he had refused to announce his plans.[36] Stone stated that he believed Quay's trial had been political persecution, and wanted to raise the issue now rather than later. There was much discussion as to whether the Senate would seat Quay, given that the legislature had had the opportunity to fill the seat but had not done so. In a similar 1893 case involving a Montana Senate seat, it had refused to seat the appointee.[40] According to Kehl, Stone would have been better advised to recall the legislature into special session in the hope the acquittal would cause them to reach a decision, but the governor wanted to rebuke Wanamaker and endorse Quay.[38] Wanamaker mounted a campaign to get the Senate to refuse to seat Quay when the new congressional session began in December 1899.[41] In this, he was joined by some newspapers who warned Republican senators to avoid giving the Democrats ammunition for the 1900 elections by having the Republican Senate accept someone rejected by his own state legislature.[42]

When Congress convened on December 4, 1899, Quay's credentials were referred to the Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections, as was a petition signed by 78 members of the Pennsylvania legislature, urging the Senate not to seat Quay.[43] On January 4, 1900, George Hoar of Massachusetts, a Republican member of the committee, told the Senate that he was daily receiving many letters urging him to oppose Quay's seating, in common, he believed, with other members of the Senate.[44]

On January 23, 1900, the committee reported back,[44] and recommended that Quay not be seated, by a 5–4 vote,[34] with Hoar voting in the minority.[45] It held that governors lacked the constitutional authority to make appointments when legislatures deadlocked,[46] and that governors could only appoint when a vacancy began during the recess of the legislature.[47] One Republican joined four Democrats to produce the majority, with the remaining four Republicans in the minority.[48]

Quay's seating was debated intermittently over the following three months by the Senate,[45] which at last voted on April 24, 1900.[49] Wanamaker got former president Benjamin Harrison, who had appointed him postmaster general, to use his influence to defeat Quay. Harrison convinced Republican senators from his home state, Indiana, as well as those former members of his administration who were in the Senate, to vote against seating Quay.[41] The Senate refused to seat Quay by a vote of 33–32 in a vote that cut across party lines, with the Republicans against Quay including his fellow political boss, Ohio's Mark Hanna.[49][50] Hanna, in addition to being a senator, was President William McKinley's closest advisor, and had run his 1896 campaign for the presidency.[51]

Quay would avenge himself on Hanna by assisting New York's Thomas C. Platt at the 1900 Republican National Convention. Platt wanted to politically sideline his state's governor, Theodore Roosevelt, by making him vice president. Despite Hanna's strong opposition, Platt and Quay got the nomination for Roosevelt.[52] According to historian Lewis L. Gould, while Quay desired to gratify his old friend and co-worker, Platt, it was "more especially to embarrass and defeat if possible the wishes of Senator Hanna, who had opposed his being seated in the Senate of the United States upon the certificate of the Governor of Pennsylvania".[52] As Hanna's biographer, William H. Horner, put it, "[Early Hanna biographer Herbert] Croly observed that if not for Platt's desire to get Roosevelt out of New York and Quay's desire to get his revenge upon Hanna, Roosevelt would never have been vice president,"[53] an office from which he succeeded to the presidency with the assassination of President McKinley in September 1901.[54]

Aftermath

[edit]The fact that he was instrumental in the nomination of Roosevelt, seen as a war hero and reformer, boosted Quay, according to Kehl, "rebuild[ing] his tarnished image in the Keystone State".[55] Quay spent the 1900 campaign season giving speeches for legislative candidates who would vote for his election when the legislature convened again in 1901.[17] The results, though, favored Wanamaker's reformers.[17] When the legislature convened, Quay was able to secure, possibly through bribery, the votes of one Democrat and seven Republicans previously pledged against him to gain a slim majority. Quay was elected for the remainder of the six-year term.[56]

The election of Quay dispirited Wanamaker, who lost interest in politics.[57] Nevertheless, according to the businessman's biographer, Herbert Adams Gibbons, Quay's prestige "was irretrievably lost. The mantle of Republican boss soon passed to the shoulders of Penrose."[58] Quay died in 1904, still in office; Penrose controlled the state Republican Party until his own death in 1921 put an end to the Cameron-Quay-Penrose machine, one of the longest-lived and most powerful in the nation.[46] Public dismay at what was seen as a corrupt means of choosing federal lawmakers, and one that sometimes led to deadlock, was a major factor in the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1913, which took responsibility for electing senators from state legislators, and gave it to the people.[59]

References

[edit]- ^ Bybee, p. 510.

- ^ Schiller & Stewart, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Article I, Clause 2, Section 3 of the Constitution of the United States (1787)

- ^ Bybee, pp. 541–542.

- ^ a b c d e "Quay, Matthew Stanley". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. United States Congress. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ Blair, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Schiller & Stewart, p. 197.

- ^ Blair, p. 84.

- ^ Blair, pp. 77–80.

- ^ a b c Kehl, p. 214.

- ^ Ershkowitz, pp. 249–254.

- ^ Ershkowitz, p. 264.

- ^ a b Kehl, p. 215.

- ^ Blair, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Blair, p. 81.

- ^ Schiller & Stewart, p. 205.

- ^ a b c d e f Beers, p. 47.

- ^ Schiller & Stewart, pp. 206–207.

- ^ a b Kehl, p. 216.

- ^ Schiller & Stewart, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1901. Vol. 1. American Historical Association. 1902. p. 533.

- ^ Gibbons, p. 362.

- ^ Schiller & Stewart, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Schiller & Stewart, p. 210.

- ^ "Quay's strong showing". The Philadelphia Inquirer. January 18, 1899. pp. 1, 6. Page 6 image here

- ^ "Quay in the lead". Harrisburg Telegraph. January 19, 1899. p. 1.

- ^ a b c "U.S. Senate Election – 1899" (PDF). Pennsylvania Election Statistics, 1682–2006. Wilkes University. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ "Points in State Politics". The Times-Leader. Wilkes-Barre, Pa. February 28, 1899. p. 4.

- ^ Schiller & Stewart, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Schiller & Stewart, p. 212.

- ^ "Pennsylvania senatorial election returns". Pennsylvania Election Statistics, 1682–2006. Wilkes University. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ "Standing of the Senate". The New York Times. March 15, 1899. p. 2.

- ^ "Another Break in Quay's Ranks". Chattanooga Daily Times. April 17, 1899. p. 1.

- ^ a b Schiller & Stewart, p. 214.

- ^ "It was a very feeble bolt". The Pittsburgh Press. April 18, 1899. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Last Ballot Cast". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. April 20, 1899. p. 1.

- ^ Schiller & Stewart, p. 213.

- ^ a b Kehl, p. 218.

- ^ Taft, p. 109.

- ^ "Col. Quay is Acquitted". Adams County Independent. April 29, 1899. p. 8.

- ^ a b Ershkowitz, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Gibbons, pp. 363–364.

- ^ "Congressional Record, Vol. 33, December 4, 1899, p. 1" (PDF).

- ^ a b Taft, p. 108.

- ^ a b Taft, p. 125.

- ^ a b Schiller & Stewart, p. 215.

- ^ Taft, p. 118.

- ^ Kehl, p. 220.

- ^ a b Taft, p. 142.

- ^ Kehl, pp. 219–221.

- ^ "Marcus A. Hanna: A featured biography". United States Senate. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Gould, p. 368.

- ^ Horner, p. 263.

- ^ "William McKinley Assassination: Topics in Chronicling America". Library of Congress. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ Kehl, p. 229.

- ^ Beers, p. 49.

- ^ Ershkowitz, p. 274.

- ^ Gibbons, p. 364.

- ^ Bybee, pp. 538–540.

Bibliography

[edit]- Beers, Paul B. (2010). Pennsylvania Politics Today and Yesterday: The Tolerable Accommodation. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-04498-9.

- Blair, William Alan (April 1989). "A Practical Politician: The Boss Tactics of Matthew Stanley Quay". Pennsylvania History. 56 (2): 78–89.

- Bybee, Jay S. (Winter 1997). "Ulysses at the Mast: Democracy, Federalism, and the Sirens' Song of the Seventeenth Amendment". Northwestern University Law Review. 91 (2): 500–572. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- Ershkowitz, Herbert (1999). John Wanamaker: Philadelphia Merchant (eBook ed.). Combined Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58097-004-4.

- Gibbons, Herbert Adams (1926). John Wanamaker. Vol. 1. Harper & Brothers. OCLC 162856645.

- Gould, Lewis L. (December 1981). "Charles Warren Fairbanks and the Republican National Convention of 1900: A Memoir". Indiana Magazine of History. 77 (4): 358–372. JSTOR 27790562.

- Horner, William T. (2010). Ohio's Kingmaker: Mark Hanna, Man and Myth. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-1894-9.

- Kehl, James A. (1981). Boss Rule in the Gilded Age: Matt Quay of Pennsylvania. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-3426-4.

- Schiller, Wendy J.; Stewart III, Charles (2015). Electing the Senate : Indirect Democracy Before the Seventeenth Amendment (eBook ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16316-1.

- Taft, George S. (1903) [1885]. Compilation of Senate Election Cases from 1789 to 1885, continued to March 3, 1903. United States Government Printing Office. OCLC 1042405215.

Further reading

[edit]- Chapman, Elizabeth Ann (1924). Matthew S. Quay and the Republican Machine in Pennsylvania (Thesis). University of Wisconsin.

KSF

KSF