2010 Copiapó mining accident

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 50 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 50 min

Rescue efforts at the mine on 10 August 2010 | |

| Date |

|

|---|---|

| Time | 14:05 CLT (UTC−04:00) |

| Location | San José mine, near Copiapó, Atacama Region, Chile |

| Coordinates | 27°09′31″S 70°29′52″W / 27.158609°S 70.497655°W |

| Outcome | All 33 trapped miners rescued |

| Property damage | Total closure and loss as of August 2010[update][needs update] |

| Litigation | US$1.8 million lawsuit as of August 2010[update][needs update] |

The 2010 Copiapó mining accident, also known as the "Chilean mining accident", began on 5 August 2010, with a cave-in at the San José copper–gold mine, located in the Atacama Desert 45 kilometers (28 mi) north of the regional capital of Copiapó, in northern Chile. Thirty-three men were trapped 700 meters (2,300 ft) underground and 5 kilometers (3 mi) from the mine's entrance, and were rescued after 69 days.[1][2]

After the state-owned mining company, Codelco, took over rescue efforts from the mine's owners, exploratory boreholes were drilled. Seventeen days after the accident, a note was found taped to a drill bit pulled back to the surface: "Estamos bien en el refugio los 33" ("We are well in the shelter, the 33 of us").

Three separate drilling rig teams; nearly every Chilean government ministry; the United States' space agency, NASA; and a dozen corporations from around the world cooperated in completing the rescue. On 13 October 2010, the men were winched to the surface one at a time, in a specially built capsule, as an estimated 5.3 million people watched via video stream worldwide.[3][4][5] With few exceptions, they were in good medical condition with no long-term physical effects anticipated.[6] Private donations covered one-third of the US$20 million cost of the rescue, with the rest coming from the mine owners and the government.[7]

Previous geological instability at the old mine and a long record of safety violations for the mine's owners, San Esteban Mining Company, had resulted in a series of fines and accidents, including eight deaths, during the dozen years leading up to this accident.[8][9][10] After three years, lawsuits and investigations into the collapse concluded in August 2013 with no charges filed.[11]

Background

[edit]

Chile's long tradition in mining has made the country the world's top producer of copper.[12] An average of 34 people per year since 2000 have died in mining accidents in Chile, with a high of 43 in 2008, according to figures from the state regulatory agency "National Geology and Mining Service" (Spanish: Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería de Chile abbreviated to SERNAGEOMIN).[13]

The mine is owned by the San Esteban Mining Company, (Spanish: Compañía Minera San Esteban abbreviated to CMSE), a company notorious for operating unsafe mines. According to an official with the non-profit Chilean Safety Association, (Spanish: Asociación Chilena de Seguridad, also known as ACHS) eight workers died at the San José site between 1998 and 2010[14][9][15] while CMSE was fined 42 times between 2004 and 2010 for breaching safety regulations.[9] The mine was shut down temporarily in 2007 when relatives of a miner killed in an accident sued the company; but the mine reopened in 2008[8][9] despite non-compliance with regulations.[16] Due to budget constraints, there were only three inspectors for the Atacama Region's 884 mines during the period leading up to the most recent collapse.[9]

Prior to the accident, CMSE had ignored warnings over unsafe working conditions in its mines. According to Javier Castillo, secretary of the trade union that represents San José's miners, the company's management operates "without listening to the voice of the workers when they say that there is danger or risk". "Nobody listens to us. Then they say we're right. If they had believed the workers, we would not be lamenting this now", said Gerardo Núñez, head of the union at a nearby Candelaria Norte mine.[17]

Chilean copper mine workers are among the highest-paid miners in South America.[18] Although the accident has called mine safety in Chile into question, serious incidents at large mines are rare, particularly those owned by the state copper mining company (Codelco) or by multinational companies.[19] However, smaller mines such as the one at Copiapó have generally lower safety standards.[19] Wages at the San Jose Mine were around 20% higher than at other Chilean mines due to its poor safety record.[6][19][20]

Collapse

[edit]

The collapse occurred at 14:00 CLT on 5 August 2010.[21] Access to the depths of the mine was by a long helical roadway.[22] One man, an ore-truck driver, was able to get out, but a group of 33 men were trapped deep inside.[23] A thick dust cloud caused by the rock fall blinded the miners for as much as six hours.[24]

Initially, the trapped miners tried to escape through ventilation shafts, but the ladders required by safety codes were missing.[25][9]

Luis Urzúa, the shift supervisor, gathered his men in a room called a "refuge" and organized them and their resources. Teams were sent out to assess the vicinity.[26]

Initial search

[edit]

Rescuers attempted to bypass the rockfall at the main entryway through alternative passages but found each route blocked by fallen rock or threatened by ongoing rock movement. After a second collapse on 7 August, rescuers were forced to use heavy machinery while trying to gain access via a ventilation shaft.[27] Concerns that additional attempts to pursue this route would cause further geological movement halted attempts to reach the trapped miners through any of the existing shafts, and other means to find the men were sought.[28]

The accident happened soon after sharp criticism of the government's handling of the Chilean earthquake and tsunami. Chile's President, Sebastián Piñera, cut short an official trip to Colombia and returned to Chile in order to visit the mine.[29]

Exploratory boreholes about 16 centimeters (6.3 in) in diameter were drilled in an attempt to find the miners.[30] Out-of-date mine shaft maps complicated rescue efforts, and several boreholes drifted off-target[31] due to drilling depth and hard rock.[32] On 19 August, one of the probes reached a space where the miners were believed to be trapped, but found no signs of life.[33]

On 22 August, the eighth borehole broke through[34] at a depth of 688 meters (2,257 ft), at a ramp near the shelter where the miners had taken refuge.[35] For days the miners had heard drills approaching and had prepared notes, which they attached to the tip of the drill with insulation tape when it poked into their space. They also tapped on the drill before it was withdrawn, and these taps could be heard on the surface.[36] When the drill was withdrawn a note was attached to it: "Estamos bien en el refugio los 33" (English: "All 33 of us are fine in the shelter"). The words became the motto of the miners' survival and the rescue effort, and appeared on websites, banners and T-shirts.[37] Hours later, video cameras sent down the borehole captured the first grainy, black-and-white, silent images of the miners.[38]

Survival

[edit]

The trapped miners' emergency shelter had an area of 50 square meters (540 sq ft) with two long benches,[39] but ventilation problems had led them to move out into a tunnel.[40] In addition to the shelter, they had access to some 2 kilometers (1.2 mi) of open tunnels in which they could move around and get some exercise or privacy.[24] Food supplies were severely limited, and each of the men had lost an average of 8 kilograms (18 lb) by the time they were discovered.[40] Although the emergency supplies stocked in the shelter were intended to last only two or three days, through careful rationing, the men made their meager resources last for two weeks, only running out just before they were discovered.[41]

After leaving the hospital, miner Mario Sepúlveda said, "All 33 trapped miners, practicing a one-man, one-vote democracy, worked together to maintain the mine, look for escape routes, and keep up morale. We knew that if society broke down, we would all be doomed. Each day a different person took a bad turn. Every time that happened, we worked as a team to try to keep the morale up." He also said that some of the older miners helped to support the younger men, but all have taken an oath of silence not to reveal certain details of what happened, particularly during the early weeks of desperation.[42]

Videos sent to the surface

[edit]Shortly after their discovery, 28 of the 33 miners appeared in a 40-minute video recorded using a mini-camera delivered by the government via 1.5-metre-long (5 ft) blue plastic capsules called palomas ("doves", referring to their role as carrier pigeons). The footage showed most of the men in good spirits and reasonably healthy, though they had all lost weight.[43]

The men appeared mainly bare-chested and bearded. They were all covered with a sheen of sweat due to the high heat and humidity of the mine at that depth. Several of the miners looked very thin, and some were camera-shy. The host, Sepúlveda, avoided specifics about the health of the men and used the vague term "complicated" to refer to their situation. He did, however, work to maintain an upbeat attitude, and insisted that things were looking brighter for the trapped men.[43] The video generally portrays a positive, light atmosphere despite the grim circumstances.[43]

Leadership

[edit]"It's been a bit of a long shift", foreman Luis Urzúa joked. A man whose level-headedness and gentle humor is credited with helping keep the miners under his charge focused on survival during their 70-day underground ordeal, Urzúa kept his cool in his first audio contact with officials on the surface. He glossed over the hunger and despair he and his men felt, saying, "We're fine, waiting for you to rescue us."[44][45][46][47]

Urzúa credited majority decision-making for the trapped men's good esprit de corps and dedication to their common goal. "You just have to speak the truth and believe in democracy", he said. "Everything was voted on; we were 33 men, so 16 plus one was a majority."[44]

Following the collapse of the mine on 5 August, Urzúa had dispatched men to find out what had happened and see if escape was possible, but they could not find an exit route. "We were trying to find out what we could do and what we could not", said Urzúa. "Then we had to figure out the food." Urzúa tried to instill a philosophical acceptance of fate so they could accept their situation and move on to embrace the essential tasks of survival.[45]

Key members of the trapped group

[edit]- Luis Urzúa (54), the shift foreman who immediately recognized the gravity of the situation and the difficulty of any rescue attempt. He gathered the men in a secure "refuge" then organized them and their meager resources to cope with a long-term survival situation.[5][48] Just after the incident, he led three men to scout the tunnel. After confirming the situation, he made detailed maps of the area to aid the rescue effort. He directed the underground aspects of the rescue operation and coordinated closely with engineers on the surface over the teleconference links.[49][50]

- Florencio Ávalos (31), second in command of the group, assisted Urzúa in organizing the men. Because of his experience, physical fitness and emotional stability, he was selected as the first miner to ride the rescue capsule to the surface in case of complications during the 15-minute ascent in the cramped shaft. Naturally shy, he served as the camera operator for videos sent up to the miners’ families. He was trapped along with his younger brother Renan.[50]

- Yonni Barrios (50), became the medic of the trapped miners due to his six months of training he took to care for his elderly mother. He served the group by monitoring their health and providing detailed medical reports to the team of doctors on the surface. His fellow miners jokingly referred to him as "Dr. House", an American TV medical drama character.[32][48]

- Mario Gómez (63), the eldest miner, became the religious leader of the group, organizing a chapel with a shrine containing statues of saints as well as aiding counseling efforts by psychologists on the surface.[48][50]

- José Henríquez (54), a preacher and a miner for 33 years, served as the miners' pastor and organized daily prayers.[50]

- Mario Sepúlveda (40), served as the energetic host of the miner's video journals that were sent to the surface to reassure the world that they were doing well. The local media dubbed him "Super Mario" after the Super Mario Bros. video game for his energy, wit and humor.[50][51][52]

- Ariel Ticona (29), served as the group's communications specialist, installing and maintaining the underground portion of the telephone and videoconferencing systems sent down by the surface team.[50]

Health of the trapped miners

[edit]

On 23 August, the first voice contact was made with the miners. Doctors reported that the miners had been provided with a 5% glucose solution and a drug to prevent stomach ulcers caused by food deprivation.[53] Material was sent down the mine in palomas, which took an hour to reach the miners.[39][54] Delivery of solid food began a few days later.[54][55] Relatives were permitted to write letters, but were asked to keep them optimistic.[39]

Out of concern for their morale, rescuers were initially reluctant to tell the miners that in the worst-case scenario, the rescue might take months, with an eventual extraction date close to Christmas. However, on 25 August, the trapped men were fully briefed on the projected timeline for their rescue and the complexity of the plans involved. The mining minister later reported that the men took the potentially negative news very well.[56]

Rescue workers and consultants described the miners as a very disciplined group.[32] Psychologists and doctors worked alongside the rescue teams to ensure the miners were kept busy and mentally focused.[54][55] The men below ground confirmed their ability to contribute to the rescue operation, saying "There are a large number of professionals who are going to help in the rescue efforts from down here."[57] Psychologists believed that the miners should have a role in their own destiny as it was important to maintain motivation and optimism.[57][58][59][60]

Sanitation became an important issue in the hot, humid environment underground, and the miners took steps to maintain hygiene throughout their ordeal. "They know how to maintain their environment. They have a designated bathroom area, garbage area and are even recycling," said Dr Andrés Llarena, an anesthesiologist with the Chilean navy. "They put plastic stuff away from biological [wastes], in different holes. They are taking care of their place." The men used a natural waterfall for regular showers and received soap and shampoo from the palomas, while dirty laundry was sent out. They dug out several fresh water sources which doctors determined to be potable and were provided water purification tablets as well.[61]

Environmental and safety issues were also a primary concern. Jimmy Sánchez, the youngest of the group at 19, was assigned as the "environmental assistant", and tested the air quality daily with a hand-held computerized device that measured oxygen, carbon dioxide levels and air temperature that normally averaged 31 °C (88 °F). Teams of miners also patrolled their area to identify and prevent potential rockfalls and pry loose hazardous stones from the ceiling, while others worked to divert the streams of water from the drilling operations.[61]

Chilean Health Minister Jaime Mañalich stated, "The situation is very similar to the one experienced by astronauts who spend months on end in the International Space Station."[62] On 31 August, a team from NASA in the United States arrived in Chile to provide assistance. The team included two physicians, one psychologist, and an engineer.[63]

After the rescue, Rodrigo Figueroa, chief of the Trauma Stress and Disaster unit of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, said there were serious shortcomings in the censorship of letters to and from miners' relatives above ground and in the monitoring of activities they could undertake, as being underground had suddenly turned them back into "babies." Nevertheless, the natural strength of "the 33" kept them alive, and their natural organization into teams as a response to disaster was also part of the innate human response to threat. Figueroa went on to say that as the miners' sound minds had seen them through, they would continue to be tested as they resumed life above ground.[clarification needed][64]

Religious aspects

[edit]

The trapped miners, most of whom were Catholic, asked for religious items, including Bibles, crucifixes, rosaries, and statues of the Virgin Mary and other saints to be sent down to them.[65] After Pope Benedict XVI sent each man a rosary, these were brought to the mine by the Archbishop of Santiago, Cardinal Francisco Javier Errázuriz Ossa in person.[66] After three weeks in the mine, one man who had been civilly married to his wife 25 years earlier asked her to enter into a sacramental marriage.[67] The men set up a makeshift chapel in the mine, and Mario Gómez, the eldest miner, spiritually counseled his companions and led daily prayers.[65]

Among the miners, a number attributed religious significance to events. Mario Sepúlveda said, "I was with God, and with the Devil – and God took me."[65] Mónica Araya, the wife of the first man rescued, Florencio Ávalos, noted: "We are really religious, both my husband and I, so God was always present. It is a miracle, this rescue was so difficult, it's a grand miracle."[68]

Both government representatives and the Chilean public have repeatedly credited Divine Providence with keeping the miners alive while the Chilean public viewed their subsequent rescue as a miracle.[69] Chile's president Sebastián Piñera stated, "When the first miner emerges safe and sound, I hope all the bells of all the churches of Chile ring out forcefully, with joy and hope. Faith has moved mountains."[69] When Esteban Rojas stepped out of the rescue capsule, he immediately knelt on the ground with his hands together in prayer then raised his arms above him in adoration.[70] His wife then wrapped a tapestry bearing the image of The Virgin Mary around him as they hugged and cried.[70]

Tent city and the families

[edit]Campamento Esperanza (Camp Hope) was a tent city that sprang up in the desert as word of the mine's collapse spread. At first, relatives gathered at the mine entrance and slept in cars as they waited and prayed for word on the rescue operation's progress. As days turned into weeks, friends brought them tents and other camping supplies to provide shelter from the harsh desert climate. The encampment grew with the arrival of more friends and relatives, additional rescue and construction workers, and members of the media. Government ministers held regular briefings for the families and journalists at the camp. "We're not going to abandon this camp until we go out with the last miner left", said María Segovia, "There are 33 of them, and one is my brother".[71][72]

Many members of the miners' families at Camp Hope were devout Catholics who prayed almost constantly for the men.[73] As they waited, worried families erected memorials to the trapped men, lit candles and prayed. On a nearby hill overlooking the mine, the families placed 32 Chilean and one Bolivian flag to represent their stranded men. Small shrines were erected at the foot of each flag and amongst the tents, they placed pictures of the miners, religious icons and statues of the Virgin Mary and patron saints.[74]

María Segovia, the elder sister of drill operator Darío Segovia, became known as La Alcaldesa (the Mayoress) for her organizational skills and outspokenness.[75] As the families became more organized, the government took steps to provide some comforts, eventually providing a more private area for the relatives to avoid constant interrogation by the energetic press corps. Infrastructure such as a kitchen, canteen area, sanitary facilities and security were later added. Bulletin boards sprouted up and the local government established shuttle bus stops. Over time a school house and children's play zones were built while volunteers worked to help feed the families. Clowns entertained the children and organizations provided emotional and spiritual comfort to the waiting families.[76] Police and soldiers were brought in from Santiago to help maintain order and security with some patrolling the desert perimeter on horseback. In many respects the camp gradually grew into a small city.[77][78]

Rescue plans

[edit]Exploratory boreholes were used to locate the trapped miners, with several of these subsequently used to supply the men. The Chilean government developed a comprehensive rescue plan modeled on the successful 2002 US Quecreek Mine rescue, itself based on the 1963 German Wunder von Lengede rescue operation. Both previous rescues had used a "rescue pod" or capsule to winch trapped miners to the surface one by one. Chilean rescue crews planned to use at least three drilling technologies to create bore holes wide enough to raise the miners in custom-designed rescue pods as quickly as possible. Henry Laas – managing director of Murray & Roberts Cementation, one of the companies involved in the rescue operation – said that "the mine is old and there is concern of further collapses", and that "the rescue methodology therefore has to be carefully designed and implemented."[79]

Drilling plans

[edit]Three large escape boreholes were drilled concurrently using several types of equipment provided by multiple international corporations and based on three different access strategies. When the first (and only) escape shaft reached the miners, the three plans in operation were:

- Plan A, the Strata 950 (702 meter target depth at 90°)

- Plan B, the Schramm T130XD (638 meter target depth at 82°) was the first to reach the miners

- Plan C, a RIG-421 drill (597 meter target depth at 85°)[80]

Plan A

[edit]Plan A used an Australian built Strata 950 model raise borer[81] type drilling rig often used to create circular shafts between two levels of a mine without using explosives. Provided by South African mining company Murray & Roberts, the drill had recently finished creating a shaft for Codelco's Andina copper mine in Chile and was immediately transferred to the San José Mine. Since it weighed 31 short tons (28 t), the drill had to be shipped in pieces on a large truck convoy. The Strata 950 was the first of the three drills to begin boring an escape shaft. If the pilot hole had been completed, further drilling would have caused rock debris to fall down the hole, requiring the miners to remove several tons of debris.[82][83]

Plan B

[edit]This drill team was the first to reach the trapped miners with an escape shaft. Plan B involved a Schramm Inc. T130XD air core drill owned by Geotec S.A. (a Chilean-American joint venture drilling company) that was chosen by Drillers Supply SA (the general contractor of Plan B) to widen one of the three 14 centimetre (5.5 in) boreholes that were already keeping the miners supplied with palomas. Normally, the drills are used to drill top holes for the oil and gas industry and for mineral exploration and water wells. This system employed Chilean Drillers Supply SA (DSI) personnel, Mijali Proestakis G.M. and Partner, Igor Proestakis Tech Mgr, Greg Hall C.E.O. (who joined his team on site for the last eight days of drilling) and their 18-centimetre (7 in) drill pipe air core drill, a team of American drillers from Layne Christensen Company and specialized Down-The-Hole drilling hammers from Center Rock, Inc., of Berlin, Pennsylvania. Center Rock's president and personnel from DSI Chile were present on-site for the 33 days of drilling. While the Schramm rig, built by privately held Schramm, Inc. of West Chester, Pennsylvania, was already on the ground in Chile at the time of the mine collapse, additional drilling equipment was flown from the United States to Chile by United Parcel Service. The percussion-technology hammer drill can drill at more than 40 meters (130 ft) a day by using four hammers instead of one.[79][84][85][86]

The Schramm T-130 was directed to bore toward the workshop, a space that was accessible by the miners. The T-130 became operational on 5 September and worked in three stages. First, it needed to enlarge the 14-centimetre (5.5 in) hole to a 30-centimetre (12 in) hole. It then needed to drill the 30-centimetre (12 in) hole into a 71 centimetre (28 in) diameter hole. "If we tried to drill from a 14-centimetre (5.5 in) hole to a 71-centimetre (28 in) hole, the torque would be too high and it would ... put the drill bits under too much pressure," said Schramm, Inc. Latin American Regional Manager, Claudio Soto. However by reusing the same hole, there was still added pressure on the drill. Delays occurred because of issues with the neck of the drills caused by the angle of the drilling. Rescuers were unable to drill vertically since that would require placing the heavy rig on the unstable ground where the cave-in had happened, and the rescuers also had to avoid drilling into the production tunnels above the shelter. Soto added, during the rescue, "It's a difficult hole. It's curved and deep. The hard rock has proven to be abrasive and has worn out the steel of the drill."

Plan C

[edit]| Drilling results

Plan A, Strata 950 (85%) 702

598

Plan B, Schramm T130 (100%) 624

Plan C, RIG-421 (62%) 597

372

|

Plan C involved a Canadian-made RIG-421 oil drilling rig operated by Calgary-based Precision Drilling Corporation. It was the last drill to be added to the rescue process and went into operation on 19 September.[79] The rig, normally used for oil and gas well drilling, could theoretically drill a wide enough escape shaft in a single pass without a pilot hole. RIG-421 is a 43 meters (141 ft) tall Diesel-Electric Triple, which needed 40 truckloads to bring its components from Iquique, Chile, to Copiapó. Chosen for the rescue operation because it can drill large holes deep into the ground and is faster than mining drills,[79][87] this plan suffered major setbacks due to the difficulty of aiming a large drill at such a small target. Furthermore, the hardness of the rock caused the drill bit to wander from its intended course and it then needed to be removed, resized and repositioned, slowing drilling progress. By comparison, the drills for Plan A and Plan B could be re-aimed while still in the hole. Many family members of the miners initially had high hopes for this rig, but it was forced to reduce its drill size and so lagged behind the other attempts.[79][88][89]

Drilling results

[edit]At 08:05 CLDT on 9 October 2010, Plan B's Schramm T130XD was the first to reach the trapped miners.[90] By 8 October, the Plan A Strata 950's pilot hole had reached only 85% of the required depth (598 meters (1,962 ft)), and had not yet started widening its shaft. Plan C's RIG-421, the only machine at the site able to drill a wide enough escape shaft without a pilot hole, reached 372 meters (1,220 ft) (62%).[79][91]

The rescue operation was an international effort that involved not only technology, but the cooperation and resources of companies and individuals from around the world, including Latin America, South Africa, Australia, the United States and Canada. NASA specialists helped develop a sophisticated health agenda. Though international participation was critical to success, overall, it was a Chilean-led team effort. As one NASA specialist said during a visit early on in the rescue: "The Chileans are basically writing the book."[79]

Extraction plans

[edit]Fénix rescue capsule

[edit]

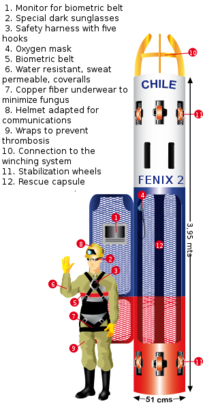

While the three drilling operations progressed, technicians worked on building the rescue capsules that would eventually carry the miners to safety.[56][79][92] Several media organizations produced illustrations of the capsules' basic design.[93][94][95]

The steel rescue capsules, dubbed Fénix (English: Phoenix) were constructed by the Chilean shipbuilding company Astilleros y Maestranzas de la Armada (ASMAR) with design input from NASA. The navy incorporated most of NASA's suggestions and produced three rescue pods: Fénix 1, 2 and 3, all enhanced versions of the Dahlbusch Bomb used for mine rescue. Fénix 1 was presented to journalists and the miners' relatives for their assessment.[79][96][97]

The eventual capsule used to rescue the 33 men was the Fénix 2, a device 54 centimeters (21 in) in diameter,[98] narrow enough to avoid hitting the sides of the tunnel. It had retractable wheels to allow for a smoother ride to the surface, an oxygen supply, lighting, video and voice communications, a reinforced roof to protect against rock falls, and an escape hatch with a safety device to allow the passenger to lower himself back down if the capsule became stuck.[79][98]

Preparations for extraction

[edit]Although drilling finished on 9 October 2010, Laurence Golborne, Chilean Minister of Mining, announced that the rescue operation was not expected to begin before 12 October due to the complex preparatory work required on both the escape shaft and the extraction system site.[99] These tasks included a borehole inspection to determine how much of the shaft needed casing to prevent rockfalls from jamming the escape capsule. Depending on the shaft casing requirement, installation of the requisite steel pipes could take up to 96 hours. After that, a large concrete platform for the winching rig to raise and lower the capsule had to be poured while the winching rig required assembly. Finally, thorough testing of the capsule and winching system together was required.

Golborne also indicated he expected only the first 100–200 meters (330–660 ft) of the shaft to be cased, a task that could be performed in only 10 hours.[100] In the end, only the first 56 meters (184 ft) were deemed to require casing. Assembly of a safe lifting system took an additional 48 hours.[101]

Shortly before the extraction phase began, Golborne told reporters that rescuers estimated it would take about an hour to bring each miner to the surface. He therefore expected the lifting phase of the rescue operation to take up to 48 hours.[102]

Rescue operation San Lorenzo

[edit]

The rescue effort to retrieve the miners began on Tuesday, 12 October at 19:00 CLT. Dubbed Operación San Lorenzo (Operation St. Lawrence) after the patron saint of miners,[74][103][104] a three-hour initial delay ensued while final safety tests were carried out. At 23:18 CLT, the first rescuer, Manuel González, an experienced rescue expert and employee of Codelco, was lowered into the mine.[105] During the 18-minute descent, the waiting families and surface rescue team members sang the Canción Nacional, Chile's national anthem. González arrived in the collapsed mine and made contact with the miners at 23:36.

Extraction

[edit]Although Chilean officials played down the risks of the rescue, the miners still needed to be alert during the ascent in case of problems. As a result, and according to the rescue plan, the first four men to be brought up the narrow shaft were those "deemed the fittest of body and mind".[106] Thereafter they would be best placed to inform the rescue team about conditions on the journey and report on the remaining miners. Once the four men had surfaced, the rescues proceeded in order of health, with the least healthy brought up from the mine first.[107]

Procedure

[edit]Six hours before the rescue, each miner switched to a liquid diet rich in sugars, minerals, and potassium.[108] Each took an aspirin to help avert blood clots,[109] and wore a girdle to stabilize blood pressure. The miners also received moisture-resistant coveralls[110] and sunglasses[111] to protect against the sudden exposure to sunlight. The capsule included oxygen masks, heart monitors, and video cameras.[97] After a miner was strapped into the 21 inches (53 cm) wide capsule, it ascended about 1 meter per second (2.2 mph), taking 9 to 18 minutes to reach the surface. Piñera was present for each arrival during the 24-hour rescue.

After an alertness check, a miner would be taken by stretcher to a field hospital for initial evaluation;[110] none needed immediate treatment. Later they were taken by helicopter to Copiapó Hospital, 60 kilometers (37 mi) away, for 24 to 48 hours of observation.[110]

Rescue

[edit]

The original plan called for two rescue workers to descend into the mine before bringing the first miner to the surface. However, to avoid delay, rescuers decided to bring a miner to the surface in the returning capsule that had taken González down. An "empty" trial run had taken place the previous day, with the capsule stopping just 15 meters (49 ft) before the end of the shaft.[112]

15 minutes later, after a further safety check, miner Florencio Ávalos began his ascent from the mine. TV cameras both inside the mine and on the surface captured the event and broadcast it worldwide. Urzúa was the last to ascend.[113]

Each transit of the capsule, whether up or down, was projected to take 15 minutes,[114] giving a total time of 33 hours for the rescue operation. In practice, after the capsule's first few transits, it became apparent that the trip might be shorter than the projected 15 minutes, and each rescue cycle should take less than 1 hour. As the eighteenth miner was brought to the surface, Chilean Mining Minister Laurence Golborne stated, "We have advanced at a faster time than we originally planned. I foresee we might conclude the whole operation before tonight."[115]

After stepping free from the rescuers and greeting his son, Urzúa embraced Piñera, saying, "I've delivered to you this shift of workers, as we agreed I would." The president replied, "I gladly receive your shift, because you completed your duty, leaving last like a good captain." Piñera went on to say, "You are not the same after this, and Chile won't be the same either."[116]

A large Chilean flag that had hung in the mine chamber during the rescue was brought up by Luis Urzúa. Once all the miners had been extracted, the rescuers in the mine chamber displayed a banner reading "Misión cumplida Chile" ("Mission accomplished Chile").[117] Manuel González was the first rescuer down and the last up, spending 25 hours 14 minutes in the mine. Rescuers needing to sleep did so in the mine to avoid tying up the capsule on rescue-delaying journeys to the surface. When the last rescuer surfaced, Piñera covered the top of the rescue shaft with a metal lid. Altogether, Fénix 2 made 39 round trips, traveling a total distance of about 50 kilometers (31 mi).[118]

Order of miners and rescuers

[edit]

Before the rescue, the trapped miners were divided into three groups to determine their exit order. From first to last these were: "hábiles" (skilled), "débiles" (weak) and "fuertes" (strong).[120] This grouping was based on the theory that the first men to exit should be those more skilled and in the best physical condition, as they would be better equipped to escape unaided in the event of a capsule malfunction or shaft collapse. They were also thought more able to communicate clearly any other problems to the surface rescue team. The second group included miners with medical problems, older men, and those with psychological issues. The final group comprised the most mentally tough, as they had to be able to endure the anxiety of the wait;[121] in the words of Minister Mañalich, "they don't care to stay another 24 hours inside the mine".

The leaving order was as shown below:

| Rescued miners | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | Name | Age[122] | Time (CLDT)[4][5] | Cycle time[123] | Comments[50] | |

| 1 | Florencio Ávalos | 31 | 13 October 00:11 | 0:51 | Recorded video footage to be sent up to families on the surface. He had helped to get his brother Renan a job in the mine. | |

| 2 | Mario Sepúlveda | 40 | 13 October 01:10 | 1:00 | An electrical specialist known as "the presenter" because he acted as a spokesman and guide on videos that the miners made. He ended one video with "Over to you in the studio." | |

| 3 | Juan Andrés Illanes | 52 | 13 October 02:07 | 0:57 | A former Chilean Army corporal who served in the Beagle Conflict, a border dispute with neighboring Argentina. | |

| 4 | Carlos Mamani | 24 | 13 October 03:11 | 1:04 | The only Bolivian among the 33, a heavy machinery operator who moved to Chile a decade prior to the incident. | |

| 5 | Jimmy Sánchez | 19 | 13 October 04:11 | 1:00 | Given the responsibility of checking air quality[124] and the youngest man trapped. He had only been a miner for five months and had just had a baby daughter. | |

| 6 | Osmán Araya | 30 | 13 October 05:35 | 1:24 | In a video message he told his wife and baby daughter Britany: "I will fight to the end to be with you." | |

| 7 | José Ojeda | 46 | 13 October 06:22 | 0:47 | Penned the famous note "Estamos bien en el refugio, los 33" (English: "We are well in the shelter, the 33"), which was discovered attached to a probe 17 days after the mine collapse.[125] He is a grandfather who suffers from kidney problems and has been on medication for diabetes. | |

| 8 | Claudio Yáñez | 34 | 13 October 07:04 | 0:42 | A drill operator. His longtime partner Cristina Núñez accepted his marriage proposal while he was underground. | |

| 9 | Mario Gómez | 63* | 13 October 08:00 | 0:56 | The eldest of the trapped miners, he had been thinking of retiring that November. (Note: *Multiple reliable sources have reported his age as between 60 and 65.) He died on September 21, 2024 at the age of 74 due to an illness.[126] | |

| 10 | Álex Vega | 31 | 13 October 08:53 | 0:53 | Suffers from kidney problems and hypertension. Had worked in the mine for nine years. | |

| 11 | Jorge Galleguillos | 56 | 13 October 09:31 | 0:38 | Suffers from hypertension. | |

| 12 | Edison Peña | 34 | 13 October 10:13 | 0:42 | The group's song leader, he requested that Elvis Presley songs be sent down the mine. The fittest miner, he had reportedly been running 10 kilometers (6.2 mi) a day while underground. He ran in the New York City Marathon in 2010[127] and 2011,[128] and the Tokyo Marathon in February 2011.[128] | |

| 13 | Carlos Barrios | 27 | 13 October 10:55 | 0:42 | A part-time miner who also drives a taxi and likes horse racing. He was said to be unhappy with interference from psychologists. | |

| 14 | Víctor Zamora | 33 | 13 October 11:32 | 0:37 | A mechanic who only went into the mine on the day of the collapse to fix a vehicle. He was also in the 2010 Chile earthquake. | |

| 15 | Víctor Segovia | 48 | 13 October 12:08 | 0:36 | An electrician and father of four who told his family: "This hell is killing me. When I sleep I dream we are in an oven." | |

| 16 | Daniel Herrera | 27 | 13 October 12:50 | 0:42 | Truck driver, was given the role of medical assistant in the mine. | |

| 17 | Omar Reygadas | 56 | 13 October 13:39 | 0:49 | A bulldozer operator whose children kept a diary of their life above ground shown on BBC News. | |

| 18 | Esteban Rojas | 44 | 13 October 14:49 | 1:10 | Told his longtime partner Jessica Yáñez that he would marry her in a church as soon as he got out. | |

| 19 | Pablo Rojas | 45 | 13 October 15:28 | 0:39 | He had worked in the mine for less than six months when the accident happened. His brother Esteban was trapped with him. | |

| 20 | Darío Segovia | 48 | 13 October 15:59 | 0:31 | A drill operator, he is the son of a miner, and his father was once trapped for a week underground. His sister María led prayers at Camp Hope, the makeshift settlement that sprang up at the mine's entrance. | |

| 21 | Yonni Barrios | 50 | 13 October 16:31 | 0:32 | Served as the group medic and supervised their medical care. | |

| 22 | Samuel Ávalos | 43 | 13 October 17:04 | 0:33 | A father-of-three who had worked in the mine for five months. | |

| 23 | Carlos Bugueño | 27 | 13 October 17:33 | 0:29 | Friends with fellow trapped miner Pedro Cortez. | |

| 24 | José Henríquez | 54 | 13 October 17:59 | 0:26 | A preacher who has worked in mining for 33 years, he had become the miners' pastor and organized daily prayers. | |

| 25 | Renán Ávalos | 29 | 13 October 18:24 | 0:25 | Trapped along with his older brother Florencio. | |

| 26 | Claudio Acuña | 44 | 13 October 18:51 | 0:27 | Had his birthday in the mine on 9 September. | |

| 27 | Franklin Lobos | 53 | 13 October 19:18 | 0:27 | A former football player known as the "magic mortar". | |

| 28 | Richard Villarroel | 27 | 13 October 19:45 | 0:27 | A mechanic who had worked in the mine for two years. | |

| 29 | Juan Carlos Aguilar | 49 | 13 October 20:13 | 0:28 | A married father of one. | |

| 30 | Raúl Bustos | 40 | 13 October 20:37 | 0:24 | A hydraulics engineer who was in the February 2010 Chile earthquake. He moved north, finding work at the mine to support his wife and two children. | |

| 31 | Pedro Cortez | 26 | 13 October 21:02 | 0:25 | Went to school near the mine. He and his friend Carlos Bugueno, who was also trapped, started work there at the same time. | |

| 32 | Ariel Ticona | 29 | 13 October 21:30 | 0:28 | The group's communications specialist. His wife gave birth to a daughter on 14 Sep and he watched the arrival on video. He named his daughter Esperanza, which means "Hope". | |

| 33 | Luis Urzúa | 54 | 13 October 21:55 | 0:25 | The shift foreman, known as Don Lucho by other miners, took a leading role while they were trapped and made more accurate maps of their cave for the rescue crews. | |

Note: Early in the disaster, the Chilean newspaper El Mercurio published a widely circulated, but incorrect, early list of the miners' names with two errors: it omitted Esteban Rojas and Claudio Acuña, and wrongly included the names of Roberto López Bordones and William Órdenes. The list above is correct and up to date according to the Ministry of Mining website.[129]

| Rescue workers who descended | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order descended | Rescue worker[130][131][132] | Affiliation[132][133] | Descent time (CLDT)[131] | Extraction time (CLDT)[131] | Time spent inside mine[131] | Cycle time[131][134] | Down trip no.[131] |

| 1. | Manuel González | El Teniente Mine | 12 October 23:18 | 14 October 00:32 | 25:14 | 0:27 | 1 |

| 2. | Roberto Ríos, Sgt | Chilean Marine Corps | 13 October 00:16 | 14 October 00:05 | 23:49 | 0:23 | 2 |

| 3. | Patricio Robledo, Cpl | Chilean Marine Corps | 13 October 01:18 | 13 October 23:42 | 22:24 | 0:25 | 3 |

| 4. | Jorge Bustamante | El Teniente Mine | 13 October 10:22 | 13 October 23:17 | 12:55 | 0:24 | 13 |

| 5. | Patricio Sepúlveda, Cpl | GOPE (national police medic) | 13 October 12:14 | 13 October 22:53 | 10:39 | 0:23 | 16 |

| 6. | Pedro Rivero | Carola Mine | 13 October 19:23 | 13 October 22:30 | 3:07 | 0:35 | 28 |

Notes:

- The extraction times for the rescuers are correct but may be out of order and not listed next to the actual corresponding rescue worker.

- "Down trip no." is the sequence number of the capsule journey that he was sent down on.

Timeline of events

[edit]2010 Copiapó mining accident timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

−5 — – 0 — – 5 — – 10 — – 15 — – 20 — – 25 — – 30 — – 35 — – 40 — – 45 — – 50 — – 55 — – 60 — – 65 — – 70 — – 75 — – 80 — – 85 — – 90 — | A B C |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Day 01 = 5 August 2010 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

This is a general chronology of the events, from the beginning:

- 5 August 2010: Rock-fall at the San José mine in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile leaves 33 gold and copper miners trapped 700 metres (2,296 ft) below ground.

- 7 August 2010: Second collapse hampers rescue efforts and blocks access to lower parts of the mine. Rescuers begin drilling boreholes to send down listening devices.

- 22 August 2010: 17 days after the first collapse, a note is found attached to one of the drill bits, saying: "Estamos bien en el refugio, los 33" (English: "We are well in the shelter, the 33"). The miners were in a shelter having lunch when the first collapse occurred, and had survived on rations. Food, medical supplies, clothes and bedding began to be sent down the borehole.

- 27 August 2010: The miners send first video greetings to the surface.

- 30 August 2010: First attempt to drill a hole to rescue the men, Plan A, begins.

- 5 September 2010: Plan B drilling begins.

- 18 September 2010: Miners celebrate Chilean Bicentennial holiday underground.[135]

- 19 September 2010: Plan C drilling begins.

- 24 September 2010: Miners had now been trapped underground for 50 days, longer than anyone else in history.

- 9 October 2010: Plan B drill breaks through to the miners' workshop.

- 11 October 2010: "Fénix 2" rescue capsule is tested to ensure that it can pass up and down the newly completed shaft.

- 12 October 2010: Rescue begins at 23:20 CLDT.

- 13 October 2010: At 21:56 CLDT the last of the 33 miners is brought to the surface.[27]

- 14 October 2010: First three miners released from hospital.

- 15 October 2010: 28 more miners released from hospital, two remain for further treatment; dental and psychological follow-up.

- 16 October 2010: Mario Sepúlveda discharged from hospital after additional psychological tests.

- 19 October 2010: Víctor Zamora released from hospital after dental problems.[136]

- 25 October 2010: Rescued miners honored at the "La Moneda" presidential palace, met with President Sebastián Piñera, posed for pictures with the "Fénix 2" capsule and played a friendly game of football against a government team at the Julio Martínez Prádanos National Stadium.[137]

Reaction to the rescue

[edit]

Chilean President Sebastián Piñera and First Lady Cecilia Morel were present during the rescue. Bolivian President Evo Morales was also scheduled to be there but did not arrive in time to see the rescue of the trapped Bolivian miner, Carlos Mamani.[138] Morales visited Mamani at a hospital along with Piñera later in the day.[139] A number of foreign leaders contacted Piñera to express solidarity and pass on congratulations to Chile while rescue efforts were underway. They included the Presidents of Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Peru, South Africa, Uruguay, Venezuela,[140][141] and Poland,[142] as well as the Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom,[143] Spain and Ireland, (who also wrote personally to the Chilean president and the County Clare-based designers and manufacturers of the rescue drill).[144] Other foreign leaders including Mexican President Felipe Calderón[145] and US President Barack Obama[145][146] praised the rescue efforts and passed on their hopes and prayers to the miners and their families. Pope Benedict XVI left a video message in Spanish praying for the success of the rescue operation.[147]

After the successful rescue, Piñera gave a speech on location in which he praised Chile, saying that he was "proud to be the president of all Chileans." He invoked Chile's recently passed Bicentennial celebrations and said that the miners were rescued with "unity, hope and faith." He thanked Hugo Chávez and Morales, amongst others, for their calls of support and solidarity. He also said that those responsible for the collapse of the mine would be punished, and that there would be a "new deal" for the workers.[148][149]

Miners post-rescue

[edit]All but two of the men went home within 48 hours of their rescue, and by 19 October all had left the hospital.[150][151][152]

Doctors felt the men had coped unexpectedly well physically with their time underground. Piñera even challenged the men to a friendly football game and invited them to visit the presidential palace and the opening of a transcontinental highway.[153]

Marc Siegel, an associate professor of medicine at the New York University Langone Medical Center, said that lack of sunlight could cause problems with muscles, bones, and other organs. Jane Aubin, scientific director of the Institute of Musculoskeletal Health and Arthritis at the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, said the miners would have to be monitored closely: "They haven't been as physically active as you would want [them] to be, so they have undoubtedly experienced some muscle loss. ... Probably after that extended period of time, in both a confined space and in relative darkness, they've also probably experienced some bone loss."[154]

Officials considered canceling plans for a Thanksgiving Mass for the men and their families at Camp Hope on 17 October over fears that a premature return to the site could be too stressful. "It's not a good idea that they go back to the mine so soon", said psychologist Iturra.[152] Jorge Díaz, head of the miners' medical team at Copiapó regional hospital, said: "We have a group of workers who are absolutely normal people, they weren't selected from a group of applicants to be astronauts, nor were they people who underwent rigorous tests, therefore we don't know when the post-traumatic stress syndrome can appear."[155]

In the years after the accident, although initially they enjoyed worldwide fame, gifts of motorcycles, and invitations to Disney World and the Greek Islands, many spiraled, suffering psychologically and financially. Some found they could not get new mining jobs due to concerns that potential employers had about their mental health and the publicity that could follow. Some, like Jorge Galleguillos, adapted by finding related work, leading tours around the San Jose mining site. Others battled alcohol and drug addiction. Mario Sepulveda, who was called "Super Mario" for his positive and energetic personality admitted to fighting suicidal thoughts, saying, "People saw the pictures of the rescue and they thought our hell was over. In fact it was just beginning."[156]

Activities

[edit]On Sunday, 17 October 2010, six of the 33 rescued miners attended a multi-denominational memorial Mass led by an evangelical pastor and a Roman Catholic priest at "Campamento Esperanza" (Camp Hope) where anxious relatives had awaited the men's return. Some of the rescuers who helped bring the miners to the surface also attended.[151][155] Reporters and cameras mobbed the miners, prompting the police to intervene to protect them. Omar Reygadas' family was swarmed by the media after they left the service, and his 2-year-old great-granddaughter started crying when pushed by the crowd. As Reygadas picked her up, the cameras zoomed in. Reygadas stayed calm but offered his only answer in response to their questions: "I've had nightmares these days", Reygadas said from inside a small tent while reporters jockeyed for position, "but the worst nightmare is all of you."[157]

Based on their experience, the miners plan to start a foundation to help in the field of mine safety. Yonni Barrios said: "We're thinking about creating a foundation to solve [safety] problems in the mining industry. With this, with the experience that we had had, God help us, we should be able to solve these problems." Juan Illanes told El Mercurio: "We have to decide how to direct our project so this type of thing never happens again. It needs to be done, but these things don't happen quickly".[158]

On 24 October 2010, the miners attended a reception hosted by Piñera at the presidential palace in the capital, Santiago, and were awarded medals celebrating Chile's independence bicentennial. Outside, the men posed for photographs next to the Fénix rescue capsule that had winched them to the surface, now installed in the main square in Santiago. Afterwards, at the National Stadium, the freed miners played a football match against a team that included Piñera; Laurence Golborne, the mining minister; and Jaime Manalich, the health minister. Team "Esperanza" (Hope), led by Franklin Lobos, all wore the number "33", but lost 3–2 to the government team.[159]

In November 2010, miners visited Los Angeles, appearing in a taping of CNN "Heroes."[160] On 13 December 2010, 26 of the rescued miners, including Franklin Lobos, went on invitation to a Manchester United training session at Carrington, Greater Manchester in England.[161] In February 2011, 31 of the 33 miners were hosted by the Israeli Ministry of Tourism for an eight-day pilgrimage of Christian and Jewish holy sites.[162]

Legacy and aftermath

[edit]

Political

[edit]Immediately following the San José mine collapse, Piñera dismissed top officials from the Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería de Chile (SERNAGEOMIN), Chile's mining regulatory agency and vowed to undertake a major overhaul of the department in light of the accident.[14] In the days following the collapse, eighteen mines were shut down and a further 300 put under threat of possible closure.[163]

On 25 October 2010, ahead of schedule, Piñera received a preliminary report by the Commission on Work Safety established in response to the incident. The report was a direct result of the Copiapó accident and contained 30 proposals ranging from improvements in hygiene to better coordination between local regulatory authorities. Although the commission had set 22 November 2010 as the date to deliver its final report, it reported that job safety inspections in Santiago and regions throughout Chile had allowed them to obtain a clear picture of the situation earlier than anticipated. In total, the commission held 204 hearings and reviewed 119 suggestions that came from online input.[164] Throughout the incident, Piñera stressed that cost was of no object with regard to rescuing the miners. The operation was expensive with estimates surpassing US$20 million, excluding expenses in building, maintaining and securing "Campamento Esperanza" (Camp Hope). These costs exceed the total business debt of the mine's owner, the San Esteban Mining Company, which currently stands at around US$19 million. The state mining company Codelco contributed about 75% to rescue costs with private companies donating services worth more than US$5 million.[165]

The French credit rating agency Coface declared that the dramatic mining rescue would have a positive impact on Chile's economic reputation. "It provides to international investors an image of a country where you can do safe [sic] business", Coface's UK managing director, Xavier Denecker, said. "It gives a good impression in terms of technology, solidarity and efficiency." Coface rates countries according to the probability of private sector companies being successful. Chile holds its highest rating in South America: A2. The UK, in comparison, is rated at A3.[166]

Legal

[edit]Following the accident, a lawsuit was filed against the San Esteban Mining Company by relatives of those trapped, while a judge froze US$2 million of its assets. A lawyer for several of the miners' families described this as a refutation of the company's claims of "not having even enough money to pay salaries".[163]

On 21 October, San Esteban Mining Company Operations Chief Carlos Pinilla and mine manager Pedro Simunovic issued a signed public statement insisting that no company official "had the slightest indication that a catastrophe could occur." Miner Jorge Gallardo asserted that there was no way the owners could have been unaware of the situation since he recorded everything and his daily safety reports were signed by Pinilla in person. Rescued miner Victor Zamora commented "What made me sad was that people were dying because the company did not want to have something safer and only thought about money".[164]

Social

[edit]Chilean writer and former miner Hernán Rivera Letelier wrote an article for the Spanish newspaper El País offering advice to the miners: "I hope that the avalanche of lights and cameras and flashes that is rushing towards you is a light one. It's true that you've survived a long season in hell, but, when all's said and done, it was a hell you knew. What's heading your way, now, comrades, is a hell that you have not experienced at all: the hell of the show, the alienating hell of TV sets. I've only got one thing to say to you, my friends: grab hold of your family. Don't let them go, don't let them out of your sight, don't waste them. Hold on to them as you hung on to the capsule that brought you out. It's the only way to survive this media deluge that's raining down on you."[167]

The Daily Telegraph UK newspaper reported that the miners have hired an accountant to ensure that any income from their new celebrity status is fairly divided, including money from expected book and film deals. The men have agreed to "speak as one" when they discuss their experiences. While still trapped, they appointed one of their group as official biographer and another their poet.[168]

The first TV documentary was aired by Nova on the US Public Broadcasting System on 26 October 2010.[169][170]

In 2014, the BBC reported that many of the survivors were out of work, and had not yet received compensation payments.[171]

Monument

[edit]Chilean President Sebastián Piñera has suggested turning Camp Hope into a memorial or museum in honor of the men.[136] A modest monument was built at the mine entrance.[171]

The Fénix 2 capsule used in Operación San Lorenzo has been placed in the Plaza de la Constitución, in front of Chile's presidential palace in Santiago, Chile. Currently, one of the backup capsules is in Copiapó and the other was sent to China for display in Chile's exhibit at the 2010 Shanghai Expo. Discussions are under way for a permanent display of the capsule and possibly a museum. As of December 2010[update], potential locations include Copiapó, the city closest to the accident site, and Talcahuano, 1,300 miles (2,100 km) to the south, where the capsules were built at a Chilean navy workshop.[172] The Fénix 1 capsule was a featured display at the March 2011 Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada convention in Toronto, Ontario, where Laurence Golborne and the rescue team were honored.[173] Since 3 August 2011, the Fénix 2 capsule is displayed at the Atacama Regional Museum in Copiapó.[174]

Books

[edit]While still trapped in the mine, the 33 miners chose to collectively contract with a single author to write an official history so that none of the 33 could individually profit from the experiences of others.[175][176] The miners chose Héctor Tobar, a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer at the Los Angeles Times. Tobar had exclusive access to the miners and in October 2014 published an official account titled Deep Down Dark: The Untold Stories of 33 Men Buried in a Chilean Mine, and the Miracle That Set Them Free. Tobar described the previous books published on the topic as "quick and dirty" with "almost no cooperation from the miners."[176] These books include the following:

- Trapped: How the World Rescued 33 Miners from 2,000 Feet Below the Chilean Desert (August 2011) by Marc Aronson

- Buried Alive!: How 33 Miners Survived 69 Days Deep Under the Chilean Desert (2012) by Elaine Scott

- 33 Men: Inside the Miraculous Survival and Dramatic Rescue of the Chilean Miners (October 2011) by Jonathan Franklin[169][177]

Film

[edit]A film titled The 33 based on the events of the disaster is directed by Patricia Riggen and written by Mikko Alanne and Jose Rivera. Mike Medavoy, producer of Apocalypse Now, worked with the miners, their families, and those involved to put the film together.[178] The movie stars Antonio Banderas as Mario "Super Mario" Sepulveda, the public face of video reports sent from underground about the miners' conditions. The actual Sepulveda expressed his enthusiasm and approval towards Banderas playing the role.[179] Brazilian actor Rodrigo Santoro stars as Laurence Golborne, the Chilean Minister of Mining at the time, and American actor Bob Gunton stars as Sebastián Piñera, the President of Chile at the time. The film's plot mostly focuses on the disaster and its aftermath, during which rescue teams attempt to save the trapped miners over the course of three months. According to an interview with Patricia Riggen in 2015, the miners have never been compensated monetarily for their ordeal, and many of them suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder.[180]

See also

[edit]- Sheppton Mine disaster and rescue - coal mine collapse in 1963 in Sheppton, Pennsylvania that trapped three miners, one miner died two were rescued. Was the first mine rescue to rescue miners using bore holes.

- 2006 Copiapó mining accident – resulted in two deaths.

- Shandong Qixia Gold Mine Explosion Accident – 22 Elecab miners were trapped and rescued in 2021.

- Floyd Collins – a cave explorer who died after 14 days in 1925. The accident scene was a national media frenzy.

- Kathy Fiscus – a three-year-old Californian girl who died after falling down a well in 1949 and whose two-day rescue attempt was broadcast live on radio and national TV.

- Alfredo Rampi – fell down a well and died as a six-year-old in 1981 in Italy. The rescue attempt was broadcast live for 18 hours.

- Jessica McClure – a Texas toddler who survived being trapped in a well for over two days in 1987, while the rescue operation was televised live on CNN.

- Quecreek Mine rescue – a successful rescue operation of miners using a similar rescue capsule in Pennsylvania in 2002.

- Beaconsfield Mine collapse – two of three Australian miners were rescued in 2006 after two weeks underground.

- Chasnala mining disaster – incident in India where a flood entered into a coal mine.

- Tham Luang cave rescue – successful rescue involving a football team in Thailand.

- Julen Rosello – Spanish toddler who fell in 2019 in a well and died after a rescue attempt of 13 days.

- Rayan Oram – Moroccan child who fell into a well and died in 2022.

- 2023 Uttarakhand tunnel rescue – successful rescue of 41 workers trapped inside the tunnel.

References

[edit]- ^ "Onemi confirma a 33 mineros atrapados en yacimiento en Atacama". La Tercera (in Spanish). 6 August 2010. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ Illiano, Cesar (9 October 2010). "Rescue near for Chile miners trapped for two months". Reuters AlertNet. Archived from the original on 18 October 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ "Chilean mine rescue watched by millions online", Canadian Broadcasting Corp., 14 October 2010

- ^ a b "First of 33 trapped miners reaches surface". CNN. 12 October 2010. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Hutchison, Peter; Malkin, Bonnie; Bloxham, Andy (12 October 2010). "Chile Miners Rescue: Live". London Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ a b "Chile mine rescue". BBC News. 13 October 2010. Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ "Chile's textbook mine rescue brings global respect". WBAY-TV Green Bay-Fox Cities-Northeast Wisconsin News. 13 October 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Trapped Chile miner's family sues owners and officials". BBC News. 26 August 2010. Archived from the original on 26 August 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Govan, Fiona; Aislinn Laing; Nick Allen (26 August 2010). "Families of trapped Chilean miners to sue mining firm". London Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 August 2010. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ Gopal Ethiraj (14 October 2004), 69-day trapped Chilean miners being lifted one by one to safety Archived 16 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Asian Tribune, Hallstavik, Sweden.

- ^ Bonnefoy, Pascale (1 August 2013). "Inquiry on Mine Collapse in Chile Ends With No Charges". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ Chile – Mining Encyclopedia of the Nations Copyright 2010 Advameg, Inc.

- ^ Jones, Sam (27 August 2010). "Trapped Chilean miners sing national anthem in footage from inside mine". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ a b Haroon Siddique (23 August 2010). "Chilean miners found alive – but rescue will take four months". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 24 August 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ Jennifer Yang (10 October 2010), "From collapse to rescue: Inside the Chile mine disaster", Toronto Star.

- ^ "New video gives tour of trapped miners' refuge" – Associated Press writers – Bradley Brooks and Peter Prengaman – with Federico Quilodran in Copiapo, Eduardo Gallardo in Santiago, and Michael Warren in Buenos Aires, Argentina, contributing to this report. The Associated Press, (NBC26.com) 28 August 2010 – Copyright 2010.

- ^ "Unions Say Mining Becoming More Dangerous in Chile" Archived 13 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Latin American Herald Tribune, 9 August 2010

- ^ "A worrying precedent". The Economist. 7 September 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ a b c "Celebration before a hard slog". The Economist. 23 August 2010. Archived from the original on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ "The Media Circus at Chile's San José Mine" Spiegel Online, 8 September 2010

- ^ Vila, Narayan (7 August 2010). "Amplio despliegue para rescatar a mineros atrapados". La Nación (Chile). Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ Channel 4 British TV program Buried Alive: The Chilean Mine Rescue, 8 pm to 9 pm, Wednesday 27 October 2010

- ^ Hector Tobar "Sixty-Nine Days" The New Yorker, 12 October 2010

- ^ a b Franklin, Jonathan (25 August 2010). "Chilean miners' families pitch up at Camp Hope". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Soto, Alonso (24 August 2010). "Chile sets sight on escape shaft for trapped miners". Reuters. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Franklin, Jonathan (5 September 2010). "Luis Urzua, the foreman keeping hope alive for Chile's trapped miners". The Observer. London. Archived from the original on 12 October 2010. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ a b Ross Lydall "Tears of joy as Chile miners complete their great escape" London Evening Standard, 13 October 2010

- ^ "Ministro Golborne: El acceso por la chimenea ya no es una opción" (in Spanish). Radio Cooperativa (Chile). 7 August 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ "Piñera vuelve a Chile y viajará a zona del accidente en la mina San José". La Tercera (in Spanish). 7 August 2010. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ "After 17 days, trapped Chilean miners send note they're alive" Archived 17 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine, CNN, 22 August 2010

- ^ Sherwell, Philip (28 August 2010). "Camp Hope families wait in Chile's Atacama Desert for trapped miners". London Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 August 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ a b c Prengaman, Peter (29 August 2010). "Chile miners must move tons of rocks in own rescue". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 5 September 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ^ "Timeline: Trapped Chilean miners". Reuters. 22 August 2010. Archived from the original on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ Brian McCullough (14 October 2010), "Chesco company proud to help with Chilean miner rescue" Archived 1 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, The Mercury, Pennsylvania.

- ^ "Chile: los 33 mineros están vivos, tras permanecer 17 días atrapados". La Voz (in Spanish). 22 August 2010. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ McMurtrie, Craig (24 August 2010). "Aussie drill expert called to Chile mine rescue". ABC News (Australia). Archived from the original on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ "Trapped Chile miners alive but long rescue ahead". Reuters. 22 August 2010. Archived from the original on 25 September 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ^ "Miners trapped in Chile mine for 17 days 'are alive'". BBC News. 22 August 2010. Archived from the original on 23 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ a b c "Trapped Chile miners receive food and water". BBC News. 23 August 2010. Archived from the original on 23 August 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ a b Soto, Alonso (24 August 2010). "Chile secures lifeline to trapped miners, sends aid". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ "Trapped Chile miners give video tour of confinement". BBC News. 27 August 2010. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "Freed Chile miner Mario Sepulveda reveals darkest days". The Daily Telegraph. Reuters. 17 October 2010. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Alexei Barrionnuevo (27 August 2010), "Video of the Trapped Chilean Miners Stirs a Country's Emotions", The New York Times.

- ^ a b Jude Webber and John Paul Rathbone (15 October 2010), "Man in the News: Luis Urzúa", Financial Times, London,

- ^ a b Carroll, Rory; Jonathan Franklin (14 October 2010). "Chile miners: Rescued foreman Luis Urzúa's first interview". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Chilean mine foreman works heroically to keep hope alive, Taipei Times, China, Jonathan Franklin, 7 September 2010

- ^ Alexei Barrionuevo (31 August 2010), "Forging bonds to survive below Earth's surface" Archived 23 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Herald-Tribune, US,

- ^ a b c Sutton, Robert I. (6 September 2010). "Boss Luis Urzua and the Trapped Miners in Chile: A Classic Case of a Leadership, Performance, and Humanity". Psychology Today. Archived from the original on 16 October 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ^ Franklin, Jonathan (5 September 2010). "Luis Urzúa, the foreman keeping hope alive for Chile's trapped miners". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 12 October 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nick Allen Chile miners rescue: profiles of the 33 men, London Daily Telegraph, 12 October 2010

- ^ "Súper Mario" Sepúlveda se convierte en estrella del rescate de los mineros Archived 29 July 2012 at archive.today El Nacional, 13 October 2010

- ^ "El hermano de Mario Sepúlveda destacó el buen humor del minero" Archived 8 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Cadena3, 14 October 2010

- ^ "CMineros confirman que están en perfecto estado de salud tras contacto por citófono" (in Spanish). Radio BioBio. 23 August 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ a b c "Chile miners face four-month wait for rescue". MSNBC. Associated Press. 23 August 2010. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ a b Franklin, Jonathan (27 August 2010). "NASA helping in historic rescue of trapped Chilean miners". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Chile's trapped miners told rescue could take months". BBC News. 25 August 2010. Archived from the original on 26 August 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ a b Laing, Aislinn; Nick Allen (27 August 2010). "Chile miners give video tour of cave". London Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 August 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Gael Favennec (11 October 2010), "Daily rigors of underground life to end for Chile miners", AsiaOne News, AFP

- ^ Fiona Govan "Trapped miners form micro-society to keep them sane", The Daily Telegraph, London, 3 September 2010

- ^ Victor Herrero To relieve miners' hell: Latrine, books, antidepressants?, USA Today, 26 August 2010

- ^ a b Jonathan Franklin Chilean miners: A typical day in the life of a subterranean miner, The Guardian, 9 September 2010

- ^ "Get us out of underground 'hell,' Chile miners plead". Agence France-Presse. 25 August 2010. Archived from the original on 29 August 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ "NASA Provides Assistance to Trapped Chilean Miners". NASA. 1 September 2010. Archived from the original on 4 September 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ Kara Frantzich and Ricardo Pommer, "Miners' Rescue In Chile: An Inspiring Note: We're OK, All 33", The Santiago Times. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Sibley, Robert (14 October 2010). "Reborn from the belly of the Earth: The Chilean miners could well look back on their ordeal as an experience that revealed something of their soul". Ottawa Citizen. Archived from the original on 22 October 2010.

- ^ "Holy Father gives thanks for rescue of Chilean miners", Catholic News Agency, 13 October 2010

- ^ "How will trapped Chile miners cope?". CNN. 23 August 2010. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ Franklin, Jonathan; Carroll, Rory (13 October 2010). "Chilean miners: 'We never lost faith. We knew we would be rescued'". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ a b Pappas, Stephanie, How 69 Days underground affects spirituality, MSNBC, 14 October 2010

- ^ a b Leichman, Aaron J., Prayers Persist as World Witnesses Rescue of Chilean Miners, The Christian Post, 13 October 2010

- ^ Federico Quilodrán (AP) Dinner for Chile miners – 2 spoonfuls of tuna, MSNBC.com, 24 August 2010

- ^ Reygadas Children "Chile miners: Family's diary", BBC News, August to October 2010

- ^ "Joyous families end long vigil at Chile's 'Camp Hope'". Reuters. 14 October 2010. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ a b "Faith plays key role for trapped Chilean miners, families". CNN. 9 September 2010. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ Vanessa Buschschluter High heels and hairdos: Chile countdown begins, BBC News, 11 October 2010

- ^ Moises Avila Roldan "Miners no longer in dark: rescue months away", Sydney Morning Herald, 27 August 2010

- ^ Simon Romero,Humanity Is Drawn to Scene of Rescue, The New York Times, 12 October 2010

- ^ Moffett, Matthew (28 August 2010). "Underground Dreams: Beer, Hugs and Weddings". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dominique Farrell and Dustin Zarnikow, "Miners's Recue In Chile: An Unprecendent Rescue Begins", The Santiago Times.

- ^ Page 5, San José Mine Rescue Operation presentation, Ministry of Mining, Republic of Chile

- ^ Model 950 Strata Raisebore Machine – Drill Rig Specifications PDF Archived 26 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, RUC Cementation Mining Contractors, (English)

- ^ Adrian Brown (26 August 2010), "Rescuers face tough challenge to save Chile miners", BBC News.

- ^ Brown, Adrian (26 August 2010). "Rescuers face tough challenge to save Chile miners". BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 August 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "Center Rock Drill Breaks Through to Trapped Chilean Miners". Cygnus. For Construction Pros. 11 October 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ^ Schramm Airdrill T130XD Rig Specifications PDF Archived 4 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Schramm Inc.

- ^ Shauk, Zain (14 October 2010). "Cypress driller's plan helped end miners' ordeal early". Houston Chronicle. Texas. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Precision Drilling Corpora. RIG 421 Specifications PDF Archived 15 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Precision Drilling

- ^ "Canadian effort to reach trapped Chilean miners lagging". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. 5 October 2010. Archived from the original on 9 October 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ Canadian drillers content with losing race to reach Chilean miners – for the most part, The Globe and Mail, Toronto, 10 October 2010

- ^ "La perforadora llegó al refugio donde se encuentran los mineros", La Nación, 9 October 2010.

- ^ "Estado del operativo de rescate". Ministerio de Minería. Gobierno de Chile. 8 October 2010. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ "'Phoenix' to pull Chilean miners out of the dark". Monsters and Critics. 11 October 2010. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010.

- ^ "Fénix 2 Rescue Capsule, side view, opened (Online Graphic)". ABC News. 14 September 2010.

- ^ "Fénix 2' Rescue Capsule, top view, opened (Online Graphic)". ABC News. 14 September 2010.

- ^ Images and description of the Fénix 2 BBC News Online Graphic, 12 October 2010

- ^ Parker, Laura. "To Design Miners' Escape Pod, NASA Thought Small". AOL News. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ a b "NASA-designed capsule helps free Chilean miners". The Engineer. 13 October 2010. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ^ a b Govan, Fiona (14 September 2010). "Chile miners: Engineers unveil 21 ins wide rescue capsule". London Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 17 September 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Chile mine rescue bid nears completion" Financial Times, 8 October 2010.

- ^ "El histórico rescate de los mineros arrancará el martes próximo". La Nación On-Line. 7 October 2010. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ "Evacuation of Chile miners 'likely to start Wednesday'". BBC News. 10 October 2010. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ "Chile escape mine shaft lining 'completed'". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 11 October 2010. Archived from the original on 12 October 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ "Operation St. Lawrence a success, all 33 Chilean miners saved", Asia News, 14 October 2010

- ^ "DJ First Of Trapped Chile Miners Returns To Surface In Rescue Ops" Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 12 October 2010

- ^ "Chile Rescue: First miners out after 69 days underground" Archived 16 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine – Perth Now – Copyright 2010 – The Sunday Times, 13 October 2010

- ^ Frank Bajak and Vivian Sequera, with contributions from Michael Warren and Eva Vergara Nearly half of the miners now free in Chile rescue[dead link] Associated Press, 13 October 2010; Retrieved 16 October 2010