2017 East Timorese parliamentary election

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 19 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 19 min

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

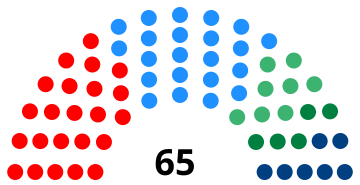

All 65 seats in the National Parliament 33 seats needed for a majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 76.74% ( | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

This lists parties that won seats. See the complete results below.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|---|

| Constitution |

|

|

Parliamentary elections were held in Timor-Leste on 22 July 2017.[1] Fretilin narrowly emerged as the largest party in the National Parliament, winning 23 seats to the 22 won by the National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction, which had been the largest party in the outgoing Parliament.

Background

[edit]After the 2012 East Timorese parliamentary election, there was first of all a coalition of the National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction (CNRT), Democratic Party (PD), and Frenti-Mudança (FM). With the exit of Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão, the new Prime Minister, on February 16, 2015, Rui Maria de Araújo. Since there was no parliamentary opposition, Taur Matan Ruak, the President of Timor-Leste, took on this role himself, leading to more conflict between the president and the rest of the government. This led to a split between the CNRT and the PD.[2][3][4][5]

The creation of the People's Liberation Party (PLP), which was shortly after led by Taur Matan Ruak as he was no longer president after the 2017 East Timorese presidential election, was a major event in the run-up to the election.[6][7] The PLP was competing for many of the same voters as the PD, which was expected to cost the PD votes. After the sudden death of PD party leader Fernando de Araújo, António da Conceição took over his positions. However, he was supported in the election by the PLP and Kmanek Haburas Unidade Nasional Timor Oan (KHUNTO).[5] The PLP also tended to use smaller rallies in its campaign than the rallies of the major parties, Fretilin and the CNRT.

Frenti-Mudança encountered difficulties, especially since Jorge da Conceição Teme, one of their top politicians, had gone over to the PDP.[5]

Some observers speculated that there would be a shift in the power structure of Timor-Leste. The younger generation had weaker ties to the old heroes of the East Timor independence campaign, and there was expected to be a greater influence from Facebook and other social media networks,[5] which are very popular with the younger generation, will have more influence than traditional media.[8]

In a nationwide poll from the International Republican Institute in November 2016, 98% of the people whom they asked were planning to go vote. 72% expected that the state of Timor-Leste would be better next year, and 49% thought it was already heading in the right direction. 29% of the sample thought that the government had done a very good job and 45% thought that the government had done a good job. 44% considered themselves to have a close connection to Fretilin and 75% had a positive opinion of the party. 29% saw the condition of roadways to be the most important issue facing the nation; 32% thought that the condition of roadways had worsened over the last year, but 29% thought that it had improved. A majority of the sample saw improvements in the areas of the healthcare system (79%), education (78%), and electricity (71%). 66% had concerns about violent riots around election time.[9]

Electoral system

[edit]The government amended some provisions in the electoral law in 2016. Exiled East Timorese were given the right to vote. For this, they have to register, which causes problems. For example, there is a larger East Timorese community in Ireland and the United Kingdom. But their members have to register at the embassy in Lisbon. In Australia, where 20,000 eligible voters are expected (out of a total of 70,000 East Timorese), there are said to be several registration offices. In Portugal and the British Isles, there are about 20,000 East Timorese, of whom about 8,000 are expected to be eligible to vote. In Timor-Leste itself, 728,363 eligible voters were registered as of August 2016, more than 153,000 of them in the national capital Dili alone.[10] The voting age was lowered to at least 16 years. For the first time, voters who had not lived during the Indonesian occupation (1975-1999) thus took part.[8] 369,000 (51%) of eligible voters are aged between 17 and 35; 118,000 (33%) are between 36 and 59 years old. 16% of voters are 60 years or older. 1,370 eligible voters are (as of December 2016) 16 years old.[10]

The 65 members of the National Parliament were elected from a single nationwide constituency by closed list proportional representation. Parties were required to have a woman in at least every third position in their list, which had resulted in 38% of MPs being female before this election,[5] with the last seat being awarded to the party with the fewest votes if there are several equal maximum numbers.[11][12][13] The government rejected the proposal to raise the three percent hurdle to five percent. Seats were allocated using the d'Hondt method with an electoral threshold of 4%.[14][15]

Voters were able to vote between 07:00 and 15:00 at 1,121 polling stations in 859 polling centres and, for the first time, at overseas stations in Australia (Sydney, Melbourne and Darwin), South Korea (Seoul), Portugal (Lisbon), and the UK (London). As many East Timorese have not registered as voters in their place of residence, the electoral authorities estimated that half of the voters would have to travel to their place of origin in another part of the country. The government has therefore declared 21 July a public holiday to facilitate travel.[16] According to the Secretáriado Técnico de Administração Eleitoral (STAE), 764,858 voters are registered. 163,129 of them live in the capital municipality of Dili alone, which is why there are 187 polling stations and 83 voting centres here alone. Baucau has 87,057 voters, Ermera 77,190 and Bobonaro 64,008, while Aileu (30,344) and Manatuto (30,344) have the fewest registered voters. 1,101 voters were registered in Australia, 589 in Portugal, 208 in the UK, and 227 in South Korea.[17]

The official election campaign began on 20 June and ran until 19 July.[18] After election day on 22 July, counting at the municipal level was scheduled to be completed by 24 July and final result known on 27 July.[19] The election result was scheduled be confirmed by the Timor-Leste Supreme Court of Justice by 6 August.[17]

International election observers came from the European Union, led by five Members of the European Parliament, National Democratic Institute (NDI) and International Republican Institute (IRI) from the United States, Australian organisations and the diplomatic corps in Dili.[16]

Parties and candidates

[edit]

Of the 31 registered parties in Timor-Leste at the beginning of 2017, only the Christian Democratic Union of Timor (UDC), KHUNTO, and the Socialist Party of Timor (PST) had submitted their electoral lists as of 30 May. 27 parties had picked up forms for the lists but had not yet filled them out and submitted them to the Timor-Leste Supreme Court of Justice. Court President Deolindo dos Santos pointed out that the country's highest court would only accept electoral lists submitted by 6pm on 1 June.[20]

Finally, a total of 23 electoral lists were submitted, with one list consisting of the party alliance Bloku Unidade Popular (BUP). Among the contesting parties were also all four factions previously represented in parliament; CNRT, Fretilin, PD, and FM.[21]

For the first time, the PLP, the Timorese Social Democratic Action Center (CASDT), the Hope of the Fatherland Party (PEP), the Democratic Unity Development Party (PUDD), and the Freedom Movement for the Maubere people (MLPM) contested.[21]

It was initially unclear whether the Timorese Social Democratic Association (ASDT) would be admitted to the election. As in 2012, two different electoral lists from different groupings of the party were received by the Supreme Court of Justice. One from party leader João Andre Avelino Correia, one from party president Francisco da Silva and secretary general Norberto Pinto. If the ASDT had still been admitted, Silva's and Pinto's list would have been recognised. However, admission was eventually denied.[21]

Five registered parties did not contest the election. The East Timor National Republic Party (PARENTIL) left the electoral alliance BUP at short notice and did not put up its own list. The Timorese Nationalist Party (PNT) had already submitted its electoral list too late in 2012 and therefore did not participate in the election. This time, too, no electoral list arrived at the court in time. The Timorese Labor Party (PTT) had contested the last election with a joint list with the Association of Timorese Heroes KOTA, but this no longer existed. The PTT did not come up with its own list. In the presidential elections at the beginning of the year, their party leader Angela Freitas had still won 0.84% of the vote. The National Unity Party (PUN) and the Liberal Party (PDL) also did not put up candidates.[21]

The last review of the submitted applications ran until June 11. The People's Party of Timor (PPT) also fell out. The party had not met the necessary eligibility criteria.[21] Already in 2012, the PPT had not been admitted because it had submitted its electoral list too late.[21] On 15 June, the order on the ballot paper was drawn.[21]

Campaign

[edit]

Observers noted an increasing professionalisation of the election campaign in Timor-Leste. Fretilin and CNRT posters dominated the street scene, but advertisements from UDT and PLP could also be seen. The CNRT relied on its leader Xanana Gusmão as its figurehead. They used the abbreviation "CR7", a reference to the footballer Cristiano Ronaldo, who is also popular in Timor-Leste. The CNRT used drones to take aerial photos of infrastructure completed under the CNRT government and other developments in the country. The video was shared on social media and in TV spots on RTTL and the new private channel GMN TV. Fretilin also promoted videos showing a vibrant and active country. They focused the campaign on the young population and also used social networks. Instead of only talking to local leaders, they also went to the markets and parks and distributed promotional material and programmes. The new PLP, which had less money than the two big parties, also relied on social networks. The PLP campaign was led by young people, many of them former journalists from President Taur Matan Ruak's press office, such as Fidelis Leite Magalhães, who appeared alongside the former president in televised debates for the PLP. The publications and debates on the internet reached 400,000 East Timorese daily, a good third of the population.[22]

While the two big parties held central campaign events in the respective municipalities, where supporters (Militantes) were driven in from all corners, the PLP held its campaign events on a smaller scale at the level of the administrative posts. On the one hand, this was due to the smaller budget, on the other hand, the idea of the grassroots movement was the inspiration here. The PLP received support in the election campaign from the Amigos de Taur Matan Ruak (A-TMR). This movement was founded by, among others, Jorge da Conceição Teme, a member of the Frenti-Mudança, and Abílio Araújo, leader of the Timorese Nationalist Party PNT. Other members belonged to the CNRT, Fretilin and other parties. Despite their affiliation to other parties, the Amigos appeared at PLP events and promoted Taur Matan Ruak and the PLP during home visits.[5]

In the election campaign, the PLP set different priorities than the Fretilin and the CNRT, especially on the issue of land development. Instead of large-scale projects, such as the special economic zone in Oe-Cusse Ambeno and the Tasi-Mane project on the south coast, the PLP wanted to focus on basic health care and educational and agricultural programmes for the population. Oe-Cusse Ambeno was under the leadership of Freilin politician Marí Alkatiri, while the South Coast project in Cova Lima was attributed to the CNRT. The PLP criticised, for example, that while there was a new highway along the south coast, the more important connecting road from Suai to Dili remained in poor condition.[5]

In 2012, KHUNTO only narrowly failed to clear the three-percent hurdle. The party is said to have particularly close ties to large local martial arts groups. Its campaign was mainly aimed at the unemployed and disillusioned youth.[13]

The non-party former president and prime minister, Nobel Peace Prize laureate José Ramos-Horta, attracted attention on social media by praising Fretilin politicians Alkatiri and Francisco Guterres for stabilising the country. However, similar words followed later about CNRT leader Xanana Gusmão and the call for PLP leader Taur Matan Ruak to reconcile with him.[5]

The election campaign was generally peaceful. Only in the municipality of Baucau were there complaints from Fretilin that former guerrillas had tried to intimidate voters.[13][23]

On the last day of the official election campaign, 19 July, the PLP held its final rally at Baucau airport and Fretilin gathered its supporters at the Nicolau Lobato monument in Dili. The moratorium until election day was generally followed. By 20 July, the election posters had disappeared from the streetscape. Only in the social networks did pictures of the parties' closing events continue to circulate.[16]

Results

[edit]

The first preliminary final result was published on 24 July, and on 27 July the CNE released the official result, which was confirmed by the Supreme Court on 1 August.[24]

In the elections, 283,350 women and 300,606 men cast their votes. Turnout was 76.74%, slightly higher than in the presidential election, and almost the same as in 2012.[25]

According to the final results, Fretilin became the strongest force with 29.7%, followed by the CNRT with 29.5%. The PLP managed to enter parliament with 10.6%, as did the PD with 9.8% and the KHUNTO, which narrowly failed in 2012, with 6.4%. Frenti-Mudança, like the other parties, failed to clear the 4 per cent hurdle.[25][26] With the PD almost maintaining its share of the vote, analysts suspect that the PLP benefited mainly from the CNRT's losses. It is also credited with great success among first-time voters, who accounted for 20% of the electorate.[13]

Fretilin won the most votes in the exclave of Oe-Cusse Ambeno, polling stations in Australia and Portugal, and in its strongholds of Baucau, Lautém, and Viqueque, municipalities in the east. The CNRT was the strongest force in the western part of the main state territory and in polling stations in South Korea and the United Kingdom. The PLP was the second strongest force in the municipality of Baucau and in the polling stations in Australia and Portugal, ahead of the CNRT, while the PD was ahead of the Fretilin in Cova Lima.[25]

Aftermath

[edit]Fretilin and CNRT began talks on a grand coalition shortly after the election.[27] On 4 August, Gusmão announced his resignation as CNRT party leader and at the same time stated that his party should not enter any government as it had been voted out by the electorate. However, Gusmão left open the possibility for CNRT members to become members of the cabinet. The negotiations with Fretilin were continued by CNRT General Secretary Francisco Kalbuadi Lay.[28][29] However, after an extraordinary congress of the CNRT spoke out against a coalition, the Fretilin announced talks with the three other parties in parliament.[30] The PD, however, demanded ministerial posts here that the Fretilin could never cede.[29] Taur Matan Ruak announced early on that the PLP wanted to play an active opposition role in parliament.[13] The PLP confirmed this in the negotiations with Fretilin, but they would not force new elections or block the budget. Therefore, the negotiations amounted to a minority government of Fretilin and KHUNTO, with the acquiescence of the PD.[29] Later, Fretilin General Secretary Marí Alkatiri explained that the coalition negotiations with the PLP had failed because they wanted Fidelis Leite Magalhães to be President of Parliament. However, there was no support for him.[31]

The members of the newly elected parliament were to be sworn in on 21 August, but the first session was postponed. They wanted to wait for the return of Xanana Gusmão. He was abroad for negotiations on the border dispute between Australia and Timor-Leste.[32] Until then, the old parliament and government acted as a transition. The non-governmental organisation Fundasaun Mahein criticised that this was not in accordance with the constitution, as the new parliament should have convened within 15 days after the Supreme Court confirmed the result.[33]

After Gusmão's return, parliament met for the first time on 5 September 2017.[34] Aniceto Guterres Lopes (Fretilin) was elected President of Parliament with 33 out of 65 votes. He was thus two votes short of the alliance of Fretilin, KHUNTO and PD. His opponent, the former parliamentary president Adérito Hugo da Costa (CNRT), received 32 votes.[35]

On 12 September, Marí Alkatiri confirmed that he would be nominated as prime minister by the coalition of Fretilin, PD and KHUNTO.[31] The previous head of government, Rui Maria de Araújo, lacked support within his own party. Alkatiri was already prime minister from 2002 to 2006, but had to resign prematurely due to the unrest in Timor-Leste in 2006.[36] On 13 September, Alkatiri and PD leader Mariano Sabino Lopes signed the coalition agreement. However, representatives of KHUNTO were not present. An internal dispute had arisen over participation in the government.[37] Although Fretilin and PD did not have a majority in parliament, President Guterres appointed Alkatiri as prime minister on 14 September and gave him the mandate to form a government.[38] However, KHUNTO announced that he would continue to cooperate with Fretilin and PD.[39] On 15 September, Alkatiri was sworn in as prime minister and the first members of his cabinet were sworn in.[40]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Last elections Inter-Parliamentary Union

- ^ "Maior partido timorense afasta Partido Democrático da coligação do Governo - Notícias SAPO - SAPO Notícias". 2019-06-03. Archived from the original on 2019-06-03. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ "Parlamento de Timor-Leste com nova mesa depois de quase dois meses de debate - Notícias SAPO - SAPO Notícias". 2019-06-02. Archived from the original on 2019-06-02. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ "Ministro da Educação timorense fica no Governo para garantir "estabilidade governativa"". TIMOR AGORA. 2016-05-07. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Leach, Michael (2017-07-14). "In Timor-Leste, the election campaign enters its final week • Inside Story". Inside Story. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ "TIMOR HAU NIAN DOBEN: Aderito Soares Lidera Partidu Libertasaun Popular". 2015-12-21. Archived from the original on 2015-12-21. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ "Taur Harii Partidu Tanba Kauza Lei Pensaun Vitalísia | Matadalan". 2015-12-21. Archived from the original on 2015-12-21. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ a b Sapo Notícias: Ano decisivo em Timor-Leste com eleições presidenciais e legislativas, 19. Dezember 2016 Archived 2019-06-08 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on 19. December 2016.

- ^ "Timor-Leste: Poll Reveals Widespread Optimism, Overwhelming Intent to Vote in Upcoming Elections". International Republican Institute. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ^ a b Sapo Notícias: "Governo altera leis eleitorais para que timorenses em Portugal e na Austrália possam votar, 16 December 2016". Archived from the original on 2019-06-03. Retrieved 2023-01-30., retrieved on 16 December 2016.

- ^ "IFES Election Guide - Election Profile for Timor-Leste". 2012-12-10. Archived from the original on 2012-12-10. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Electoral Act 06/2006" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-04. Retrieved 2023-01-30. (PDF; 812 kB) und "Amended in 06/2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-04. Retrieved 2023-01-30. (Portuguese; PDF; 173 kB), Retrieved on 7 July 2012

- ^ a b c d e Leach, Michael (24 July 2017). "Timor-Leste elections suggest reframed cross-party government". www.lowyinstitute.org. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ^ Electoral system Inter-Parliamentary Union

- ^ Fourth amendment to the Law on Election of the National Parliament: Article 13.2 Archived 2018-06-19 at the Wayback Machine CNE

- ^ a b c "Timor-Leste/Eleições: Da euforia da campanha à calma da reflexão, sem cartazes". www.dn.pt (in European Portuguese). 20 July 2017. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ^ a b "Timor-Leste/Eleições: Timorenses terão mais sítios para votar nas legislativas de 22 de julho". www.dn.pt (in European Portuguese). 22 June 2017. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ^ "Preparations for Parliamentary Elections On Track as Campaign Period Begins « Government of Timor-Leste". Diário de Notícias. 2017-06-21. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ^ "Apenas uma coligação se apresentará a eleições parlamentares em Timor-Leste". TIMOR AGORA. 26 May 2017. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ^ "UDC-PST-KHUNTO Ohin Hatama Ona Lista Kandidatura Ba TR". TATOLI Agência Noticiosa de Timor-Leste. 2017-05-30. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Timor-Leste/Eleições: 23 candidaturas apresentadas às eleições parlamentares de 22 de julho". www.dn.pt (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ "Timor-Leste/Eleições: A campanha mais profissional e sofisticada de sempre". www.dn.pt (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- ^ Murdoch, Lindsay (2017-07-21). "Accusations of voter intimidation ahead of East Timor elections". The Age. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- ^ "Confirmada vitória da Fretilin em Timor-Leste". Diário de Notícias (in European Portuguese). 2017-07-27. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ a b c "Preliminary final score as of July 27, 2017". CNE. Archived from the original on 14 November 2019 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "Who is in Timor-Leste's new Parliament? / Se tuir iha Parlamentu Nasionál foun?". La'o Hamutuk. 2017-07-23. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ "Alkatiri-Xanana Kontaktu Malu Forma Governu". Jornal Independente. 24 July 2017. Archived from the original on 19 Oct 2018 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "Xanana Rezigna-an Hosi Presidente Partidu". Tafara.tl. Archived from the original on 2017-08-05. Retrieved 2023-05-24 – via Archive.org.

- ^ a b c Kingsbury, Damien (2017-08-11). "Deakin Speaking: Timor-Leste heading towards minority, but stable, government". Deakin University. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ "Fretilin inicia quarta-feira contactos com partidos para formar próximo Governo timorense". Diário de Notícias (in European Portuguese). 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ a b "Mari Alkatiri confirma indigitação pela coligação para liderar próximo Governo timorense". Diário de Notícias (in European Portuguese). 2017-09-12. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ "Timor-Leste postpones re-opening of parliament - UCA News". ucanews.com. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ "The Post-Election Situation: "Between Constitutionality and Arbitrary Rule" (PDF). Fundasaun Mahein. 25 August 2017.

- ^ "Ohin, Deputadu IV Lejizlatura Plenária Dahuluk". TATOLI Agência Noticiosa de Timor-Leste. 2017-09-05. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ "Chefe da bancada da Fretilin eleito para a presidência do Parlamento timorense". www.dn.pt (in European Portuguese). 2017-09-05. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ "Mari Alkatiri é o nome mais apontado para chefiar o próximo Governo timorense". Diário de Notícias (in European Portuguese). 2017-08-16. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ "Fretilin e PD assinam acordo de coligação para próximo Governo timorense". Diário de Notícias (in European Portuguese). 2017-09-13. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ "Presidente assina decreto de indigitação de Mari Alkatiri como primeiro-ministro - Cm ao Minuto - Correio da Manhã". Cofina Media. 2017-09-14. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 2023-05-24 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "KHUNTO Koopera ho Partidu Koligasaun". TATOLI Agência Noticiosa de Timor-Leste. 2017-09-13. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ "VII Governo constitucional de Timor-Leste toma hoje posse incompleto". SAPO 24 (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-05-24.

Further reading

[edit]- Leach, Michael (14 July 2017). "In Timor-Leste, the election campaign enters its final week". Inside Story. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ——————— (24 July 2017). "Timor-Leste elections suggest reframed cross-party government". The Interpreter. Lowy Institute. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ——————— (8 August 2017). "Post-election, Timor-Leste faces unexpected political uncertainty". Inside Story. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- "Timor-Leste Parliamentary Elections July 22, 2017" (PDF). International Republican Institute. 2017.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to East Timor parlamentary election, 2017 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to East Timor parlamentary election, 2017 at Wikimedia Commons

KSF

KSF