2024 Russian presidential election

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 42 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 42 min

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Registered | 113,011,059 | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 77.49% ( | |||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

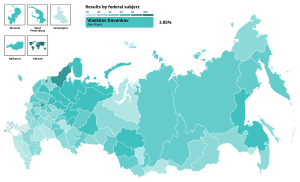

Official results by federal subject | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential elections were held in Russia from 15 to 17 March 2024.[1][2][a] It was the eighth presidential election in the country. The incumbent president Vladimir Putin won with 88% of the vote, the highest percentage in a presidential election in post-Soviet Russia,[4] gaining a fifth term in what was widely viewed as a foregone conclusion.[5][6] He was inaugurated on 7 May 2024.[7][8]

In November 2023, Boris Nadezhdin, a former member of the State Duma, became the first person backed by a registered political party to announce his candidacy, running on an anti-war platform.[9] He was followed by incumbent and independent candidate Vladimir Putin in December 2023, who was eligible to seek re-election as a result of the 2020 constitutional amendments.[10][11][12] Later the same month, Leonid Slutsky of the Liberal Democratic Party, Nikolay Kharitonov of the Communist Party and Vladislav Davankov of New People announced their candidacies.

Other candidates also declared their candidacy but were barred for various reasons by the Central Election Commission (CEC). As was the case in the 2018 presidential election, the most prominent opposition leader,[13][14] Alexei Navalny, was barred from running due to a prior criminal conviction seen as politically motivated.[15][16][17] Navalny died in prison in February 2024, weeks before the election, under suspicious circumstances.[18][19] Nadezhdin, despite passing the initial stages of the process, on 8 February 2024, was also barred from running. The decision was announced at a special CEC session, citing alleged irregularities in the signatures of voters supporting his candidacy. Nadezhdin's status as the only explicitly anti-war candidate was widely regarded as the real reason for his disqualification, although Davankov promised "peace and negotiations on our own terms".[20][21] As a result, Putin faced no credible opposition.[22][23] Anti-Putin activists called on voters to spoil their ballot. The elections saw 1.4 million invalid or blank ballots cast, around 1.6% of all votes cast, a 45 percent increase compared to the 2018 elections.

Most international observers did not expect the election to be either free or fair,[24] with Putin having increased political repressions after launching his full-scale war with Ukraine in 2022.[25][26] The elections were also held in the Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine.[26][22][27] There were reports of irregularities, including ballot stuffing and coercion,[28][29] with statistical analysis suggesting unprecedented levels of fraud in the 2024 elections.[30]

Eligibility

[edit]According to clause 3 of article 81 of the Constitution of Russia, prior to the 2020 constitutional revision, the same person could not hold the position of President of the Russian Federation for more than two consecutive terms, which allowed Vladimir Putin to become president in 2012 for a third term not consecutive with his prior terms.[31] The constitutional reform established a hard limit of two terms overall. However, terms served before the constitutional revision do not count, which gives Putin eligibility for two more presidential terms until 2036.[32]

According to the new version of the Constitution, presidential candidates must:[33]

- Be at least 35 years old (the requirement has not changed);

- Be a resident in Russia for at least 25 years (previously 10 years);

- Not have foreign citizenship or residence permit in a foreign country, neither at the time of the election nor at any time before (new requirement).

Candidates

[edit]The individuals below appeared on the ballot.[34]

| Name, age, political party |

Experience | Home region | Campaign | Details | Registration date | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vladislav Davankov (40) New People |

|

Deputy Chairman of the State Duma (2021–present) Member of the State Duma (2021–present) |

(Campaign • Website) |

Davankov was nominated by his party in December 2023 during the party's congress. He was also supported by Party of Growth, which announced that it would merge with New People. Davankov submitted documents to participate in the election on 25 December 2023 and 1 January 2024.[35][36] | 5 January 2024 | ||

| Vladimir Putin (71) Independent |

|

Incumbent President of Russia (2000–2008 and 2012–present) Prime Minister of Russia (1999–2000 and 2008–2012) FSB Director (1998–1999) |

(Campaign • Website Archived 14 March 2024 at the Wayback Machine) |

During a ceremony to award soldiers in December 2023, Putin announced that he would participate in the election. He is supported by United Russia and A Just Russia – For Truth, among others.

Putin submitted documents to participate in the election on 18 December 2023, which were registered on 20 December.[37][38] The CEC analyzed 60,000 signatures out of the 315,000 submitted by Putin, and found that only 91 (0.15%) were invalid, which is significantly below the 5% threshold.[39] |

29 January 2024 | ||

| Leonid Slutsky (56) Liberal Democratic Party |

|

Leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (2022–present) Member of the State Duma (1999–present) |

(Campaign • Website Archived 11 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine) |

Slutsky was nominated by his party in December 2023 during the party's congress. He submitted documents to the CEC on 25 December 2023 and 1 January 2024.[40][41] | 5 January 2024 | ||

| Nikolay Kharitonov (75) Communist Party |

|

Member of the State Duma (1993–present) |

(Campaign) |

Kharitonov was nominated by his party in December 2023 during the party's congress. He previously ran in the 2004 presidential election and came second with 13.7% of the vote. Kharitonov submitted documents to participate in the election on 27 December 2023 and 3 January 2024.[citation needed] | 9 January 2024 | ||

Rejected candidates

[edit]Individuals in this section have had their document submissions accepted by the CEC to register their participation, and later gathered the necessary signatures from voters. The deadline to submit documents was 27 December 2023 for independents and 1 January 2024 for party-based nominations, with the commission already announcing the rejection of some candidates based on alleged issues with their paperwork.[40]

Towards the deadline to submit documents, the CEC stated that 33 potential candidates were intending to be registered as candidates (24 independents and 9 party-based nominations). The commission accepted the documents of 15 candidates.[42]

The next step was to collect signatures by 31 January 2024. Independents had to gather 300,000 signatures from the public in at least 40 of Russia's federal subjects to support their participation and thereby be included on the ballot, while potential candidates nominated by political parties that are not represented in the State Duma or in at least a third of the country's regional parliaments had to gather 100,000 signatures.[43]

Vladimir Putin was the first to achieve this, having gathered more than half a million signatures by 30 December; by 17 January he had gathered 2.5 million signatures.[44][45] He was followed by Davankov, Kharitonov, Slutsky, Nadezhdin and Malinkovich (in no particular order). Others either failed to achieve this or withdrew from the process.[citation needed]

The CEC accepted the signatures of Putin, while rejecting Nadezhdin and Malinkovich on the basis of what it described to be irregularities. Davankov, Kharitonov and Slutsky were not required to collect signatures as they were nominated by political parties represented in the State Duma. This confirmed the final number of candidates at four.[citation needed]

| Potential candidate's name, age, political party |

Experience | Home region | Campaign | Details | Signatures collected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sergey Malinkovich (48) Communists of Russia |

Member of the Altai Krai Legislative Assembly (2021–present) Chairman of the Central Committee of the Communists of Russia (2022–present) |

(Campaign) | On 28 December 2023, Malinkovich was nominated as the candidate for his party. He submitted documents to register with the CEC on 1 January 2024.[46] On 2 February, the CEC informed Malinkovich that it had found deficiencies in the signatures he had submitted. | Signatures collected 104,998 / 105,000 [47]Signatures accepted 96,019 / 105,000 [48]

| |||

| Boris Nadezhdin (60) Civic Initiative |

|

Member of the Dolgoprudny City Council (1990–1997, 2019–present) Founder and President of the Institute of Regional Projects and Legislation Foundation (2001–present) Member of the State Duma (1999–2003) |

(Campaign • Website) |

On 31 October 2023, Nadezhdin announced that he would run from the Civic Initiative party.[49] On 26 December he submitted registration documents to the CEC, which were registered on 28 December.[50] On 8 February 2024, the CEC announced that more than 5% of the signatures it had reviewed were invalid and therefore could not register him as a candidate.[51] Nadezhdin subsequently appealed the decision at Russia's Supreme Court. | Signatures collected 105,000 / 105,000

Signatures accepted 95,587 / 105,000 [48] Supreme Court appeals[53] Case 1[c]

Cases 2 & 3[d]

| ||

Party congresses and primaries

[edit]Congresses of political parties are held after the official appointment of election. At the congress, a party can either nominate its own candidate, or support a candidate nominated by another party or an independent candidate. Twelve parties held party congresses in December 2023, at which candidates were either nominated or endorsed.

| Party | Congress date | Venue | Nominee | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Russia | 17 December 2023 | VDNKh, Moscow | Endorsement of Vladimir Putin | [54] | |

| Liberal Democratic Party | 19 December 2023 | Crocus Expo, Krasnogorsk, Moscow Oblast |

Leonid Slutsky | [40] | |

| Civic Initiative | 23 December 2023 | Moscow | Boris Nadezhdin | [55] | |

| Communist Party | 23 December 2023 | Snegiri wellness complex, Rozhdestveno, Moscow Oblast |

Nikolay Kharitonov | [56] | |

| A Just Russia – For Truth | 23 December 2023 | Holiday Inn Sokolniki, Moscow | Endorsement of Vladimir Putin | [57] | |

| Party of Social Protection | 23 December 2023 | Moscow | Vladimir Mikhailov | [58] | |

| Russian All-People's Union | 23 December 2023 | Moscow | Sergey Baburin (Declined; endorsed Vladimir Putin) |

[59][60] | |

| Party of Growth | 24 December 2023 | Moscow State University, Moscow | Vladislav Davankov | [61] | |

| New People | [62] | ||||

| Russian Party of Freedom and Justice | 24 December 2023 | Moscow | Andrey Bogdanov | [63] | |

| Democratic Party of Russia | 25 December 2023 | Moscow | Irina Sviridova (Declined; endorsed Vladimir Putin) |

[64] | |

| Communists of Russia | 28 December 2023 | Moscow | Sergey Malinkovich | [65] | |

Other parties

[edit]At Yabloko's congress, which took place on 9 December 2023, somewhat unconventionally, the party decided that Grigory Yavlinsky would run for president as its nominee if he obtains 10 million signatures from potential voters,[66] which is higher than the total number of votes Yavlinsky obtained during his most successful run for president (5.55 million).[67] Yabloko later stated that it would not be nominating any candidate.[68] Furthermore, Yavlinsky only managed to gather around a million signatures.[69]

The Left Front stated that it would run a primary election between 22 candidates, but later announced it would not be holding the primary due to threats received from the police.[70] Instead, the party called on their "comrades in the Communist Party" to vote for one of the following to be nominated at the party congress: Pavel Grudinin, Nikolai Bondarenko, Valentin Konovalov, Andrey Klychkov, Sergey Levchenko, Nina Ostanina, Igor Girkin.[citation needed]

Preparation of public opinion

[edit]In June 2023, a few posters advocating for Yevgeny Prigozhin, leader of the Wagner Group private military company, were noticed[71] in Krasnodar, with a QR code to a website hinting at the 2024 election.[72] Prigozhin himself denied any relation to such posters and "any political activity in the internet",[72] but fuelled speculation that he was about to go into politics after holding press conferences across Russia[71] and leading the Wagner Group rebellion. He died in a plane crash later that year.

According to an investigation published in February 2024 by a coalition of journals including VSquare, Delfi, Expressen and Paper Trail Media, Putin ordered Decree Number 2016, titled "On deputy heads responsible for social and political work of federal government agencies", on 17 February 2023. The decree stated its aim of coordination between the Ministry of Education and Science and other state agencies to "increase the number of voters and the support of the main candidates" in the 2024 presidential election and other elections. Documents from a governmental "non-profit organisation", ANO Integration, highlighted the emphasis on increasing the number of voters and the support of the main candidates, with turnout being used to indicate the scale of support and opposition to Putin.[73][74]

The ANO Integration documents presented a plan to create lists of all employees and sub-lists of opinion leaders in institutions within the ministry's responsibility, and to monitor political attitudes and voting preferences and "increas[e] [the employee's] level of socio-political literacy". The documents planned for the preparation of secret instructions for social events in which selected opinion leaders and "experts" would meet with students and teachers in preparation for the election. Martin Kragh of the Center for East European Studies in Stockholm described the documents by stating, "All these documents show how little the Kremlin believes that people might just spontaneously support the ruling party". Mark Galeotti, a British historian, lecturer and writer, described the process as "pre-rigging" the election in order to minimise the amount of manipulation needed in the numbers of votes cast for Putin in the election. He stated, "The Kremlin cannot even trust what mayors and governors tell them about the [political] situation in their region."[73][75][76]

When asked by a BBC journalist about his electoral campaign, Nikolay Kharitonov refused to answer why he thought he would be a better candidate than Putin, before proceeding to praise the latter for "trying to solve a lot of the problems of the 1990s" and consolidating the country for "victory in all areas".[77] Shortly after filing his candidacy in December 2023, Leonid Slutsky said he did not "dream of beating Putin" and predicted that the latter would achieve "a huge victory".[78] Vladislav Davankov said he would not criticize his political opponents.[79]

Conduct

[edit]Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine

[edit]Early voting opened on 26 February and lasted until 14 March to allow certain residents in remote areas in 37 federal subjects of Russia as well as in the regions of Ukraine that it annexed following its invasion in 2022 to vote.[80][81] In the latter areas, a campaign called InformUIK was set up to encourage participation in the election, with its representatives going door-to-door escorted by armed men to compile voter lists and collect ballots from residences. A resident of Kherson Oblast described the elections in his area as a "comedy show", noting that households were being visited by "two locals – one holding a list of voters and the other a ballot box – and a military man with a machine gun".[82]

Russian officials also used home visits by the mobile polling stations to monitor the population and find those participating in resistance activities or refusing to obtain Russian government documents.[83] Reports also emerged of Russian-installed authorities coercing people to vote by withholding social benefits and healthcare treatment, while human rights activists said at least 27 Ukrainians were arrested for refusing to vote in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts.[29] Despite Russian electoral laws prohibiting those without Russian passports from voting, voters in occupied Ukraine were allowed to present any valid identification documents, including a Ukrainian passport or driving license.[84] In Melitopol, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, soldiers armed with machine guns sealed off apartments being visited by mobile polling teams.[85] In one instance, a man who fled his village near Mariupol, Donetsk Oblast, to Ukrainian-controlled territory following the Russian invasion alleged that his name appeared in Russian-produced voter lists and was listed as having voted for Putin by election officials.[86]

Efforts to promote turnout

[edit]

On the eve of the first round of regular voting on 14 March, Putin called on citizens to vote in order to show their unity behind his leadership, saying in a video message that "We have already shown that we can be together, defending the freedom, sovereignty and security of Russia," and urged them "not to stray from this path".[87]

Latvia-based Russian news outlet Meduza reported that Kremlin officials asked Russia's regional governments to secure 70% voter turnout and more than 80% support for Putin.[74][88]

Civil servants and employees at state-run companies were ordered to vote.[89] In Omsk, officials issued 50,000 free tickets at polling stations to first-time voters aged between 18 and 24 years of age for one Ferris wheel ride at an amusement park. In Altai Krai, voters were to be given a chance to win sanctioned goods and appliances such as an iPhone in a raffle, provided that they upload pictures on VKontakte showing them at polling stations. In Strezhevoy, Tomsk Oblast, the mayor promised free bread rolls and porridge to voters. In Sverdlovsk Oblast, authorities set up an election day trivia quiz about the region's history with and offered 2,000 smartphones, 45 apartments, 20 motorcycles, and 100 Moskvich cars as prizes, but said that correct answers would not guarantee a win. In Tatarstan, officials set a music festival in Kazan on 17 March that would be open to visitors upon presentation of a bracelet obtained at polling stations that would also guarantee free and unlimited access to public transportation, along with a chance to win in a raffle with three Lada Vesta cars at stake.[90]

Reports also emerged of pressure being exerted by authorities on students and young people to vote. Students at a construction college in Perm Krai were ordered to vote inside the campus, with the school administration pledging to monitor turnout using video surveillance cameras. At Tula State Pedagogical University, students were required to submit a photo of their ballot to prove that they voted. Its rector had also publicly endorsed Putin. At Voronezh State Pedagogical University, students said they were required to inform authorities about who they were voting for.[91]

Regular voting

[edit]

On the regular election days, polls opened at 08:00 local time in Kamchatka Krai on 15 March and are expected to close at 20:00 local time in Kaliningrad Oblast on 17 March.[87] Independent watchdogs were prevented from observing the conduct of the election, as only registered candidates and state-backed advisory bodies were allowed to send observers to polling stations. The independent election monitor Golos described the election as the "most vapid" since the 2000 election, noting that campaigning was "practically unnoticeable" and that authorities were "doing everything" to prevent people noticing that an election was taking place while state media provided less airtime to the election compared to 2018. It also described Putin's campaign as disguised by his activities as president, while his registered opponents were "demonstrably passive".[92]

On 15 March, the Kremlin published images of Putin casting his vote online using a computer in his office.[93] On the morning of the same day, the online voting system went down temporarily, with Golos and other independent electoral observers attributing the outage to the traffic generated by votes coming from workplaces.[94]

Allegations of fraud

[edit]Statistical analyses

[edit]According to a Novaya Gazeta investigation using a method proposed by mathematician Sergey Shpilkin, around 22 million of the non-online (polling booth) votes for Putin were falsified, out of 64.7 million non-online votes for Putin in total. Novaya Gazeta described the analysis showing "record levels of fraud even for a Russian presidential election".[95][96]

Meduza carried out statistical analyses on the official results released by the CEC. Based on scatter plots of the vote percentage for Putin compared to turnout, a tail in which voter turnout visually correlates to Putin support, which appeared weakly in earlier Russian presidential elections, was found by Meduza to completely dominate in 2024. "Churov's saw", a statistical effect interpreted as fraudulent in which sharp peaks at round numbers appear in voter turnout and percentage votes for Putin, was found by Meduza to have strengthened in the 2024 election, with Meduza arguing that the number of polling stations with likely fraud became the majority in 2024, while earlier the fraction of fraudulent polling stations had been a minority. Overall, Meduza stated that the 2024 presidential election "was almost certainly the most fraudulent" in "modern Russian history", and that the "sheer magnitude of fraud eclipses that of 2018".[30]

Other incidents of fraud

[edit]On 16 March, Golos released a video on social media appearing to show staff at a polling station in Krasnodar doing ballot stuffing.[97] It also said that it had received reports of attempts to inspect filled-out ballots before they were cast, and one instance in which police demanded a ballot box be opened to remove a ballot.[98] Thermochromic ink that disappears when heated was also allegedly used in Kursk and Rostov-on-Don on 15 March.[99] The usage of such ink was previously reported during the 2021 regional elections in Khimki.[100] Overall, Golos described the 2024 election as an "imitation", adding that it had not previously observed "a presidential campaign that fell so short of constitutional standards".[101]

Incidents

[edit]Attacks by Ukrainian and other armed groups

[edit]Attacks have been launched against Russian electoral institutions in occupied areas of Ukraine. On the first day of early voting on 27 February 2024, two bombs were detonated at the local offices of the United Russia party and near a polling station in Nova Kakhovka, Kherson Oblast.[82] On 6 March, a local official of the Russian Central Election Commission in Berdiansk, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, was killed by a car bomb, according to Ukrainian officials.[102] When asked about the killing, the Ukrainian-appointed governor of the oblast, Ivan Fedorov, attributed the attack to "our resistance", adding that they were linked to Ukrainian secret services and that "it is abnormal when our citizens collaborate with Russians".[82] On 15 March, an improvised explosive device was detonated inside a trash can in front of a polling station in Skadovsk, Kherson Oblast,[103] injuring five Russian soldiers.[104] On 16 March, the Russian-installed governor of Kherson Oblast, Vladimir Saldo claimed that one person was killed and four others were injured in a Ukrainian drone strike in Kakhovka, which he claimed was an attempt to disrupt voting, while TASS reported that a Ukrainian drone struck a polling station in Zaporizhzhia Oblast.[28]

During an incursion into Kursk and Belgorod Oblasts on 12 March, the Sibir Battalion, an armed Russian opposition group based in Ukraine, published a video condemning the elections, saying that "Ballots and polling stations in this case are fiction."[105] A member of the Freedom of Russia Legion, which also participated in the attacks, acknowledged that they were "timed with the so-called elections" and referred to it as a "voting method".[106] Putin also described the incursion as an attempt to "disrupt" the election and "interfere with the normal process of expressing the will of citizens".[107] Throughout the election, the border city of Belgorod was subjected to shelling and rocket attacks by Ukraine, killing two people in what most analysts believed to be an attempt to disrupt the vote and incite discontent against Putin by convincing Russians of his responsibility in bringing the war on Ukraine to Russian soil by launching the invasion in the first place, although the high turnout of 78 percent in Belgorod Oblast suggested that the strategy had led to increased support for Putin.[108]

On 25 March, the independent news outlet Mediazona reported that the Federal Security Service had arrested three people on suspicion of plotting an arson attack against a Putin campaign office in Barnaul, Altai Krai, prior to the election. One of the suspects was said to have been in contact with an "unidentified terrorist organization".[109]

Incidents involving civilians

[edit]During regular polling, several election-related incidents were reported across the country, resulting in at least 13 arrests, seven of which were for pouring liquid substances on ballot boxes and four for committing acts of arson in polling stations,[110] one of which involved a woman in Saint Petersburg who was arrested for throwing a molotov cocktail at a school hosting two polling stations after having allegedly been promised a financial incentive by a "Ukrainian Telegram channel".[111] A voting booth was also set on fire in Moscow.[112] In Podolsk, Moscow Oblast, a voter was charged with "discrediting the Russian army" and fined 30,000 rubles ($342) after spoiling her ballot by writing an unspecified message.[97] A voter in Saint Petersburg was ordered arrested on similar charges after writing the words "No to War" on her ballot.[113] Some voters uploaded images of them spoiling their ballots by writing messages such as "killer and thief" and "waiting for you in The Hague", a reference to the arrest warrant issued by the International Criminal Court against Putin over war crimes in Ukraine.[114]

On 17 March, a Moldovan national was arrested after throwing two molotov cocktails at the grounds of the Russian embassy in Chișinău, which was being used as a polling station for Russian nationals in Moldova. Moldovan police said that the man, who also claimed to be carrying Russian citizenship, "justified his action by some dissatisfaction he has with the actions of the Russian authorities".[115]

In response to the attacks on polling stations, former president and deputy chair of the Security Council of Russia Dmitry Medvedev called for charges of treason to be filed against those who vandalize polling stations for attempting to derail the vote amid the fighting in Ukraine.[114]

Cyberattacks

[edit]On 16 March, the United Russia party said its website was targeted by a cyberattack.[116]

Opinion polls

[edit]

| Fieldwork date | Polling firm |

|

|

|

|

|

Others | Undecided | Abstention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Putin | Kharitonov | Slutsky | Davankov | |||||||

| 6–10 Mar 2024 | IRPZ | 55.9% | Rejected | 5.2% | 3.2% | 9.1% | 3.1% | 19.5% | 4% | |

| 6–10 Mar 2024 | CIPKR | 55% | 5% | 4% | 4% | 1% | — | 30% | ||

| 4–6 Mar 2024 | FOM | 56% | 4% | 4% | 3% | 3% | — | 30% | ||

| 4 March 2024 | VCIOM | 56.2% | 3% | 2.25% | 4.5% | — | — | 25% | ||

| 1–5 Mar 2024 | ExtremeScan | 57% | 3% | 1% | 3% | 2% | 22% | 12% | ||

| 1–5 Mar 2024 | CIPKR | 61% | 6% | 3% | 5% | 6% | 4% | 15% | ||

| 26 Feb – 5 March 2024 | IRPZ | 56.2% | 3.2% | 2% | 5.6% | 1.5% | 31% | 0.1% | ||

| 1–4 Mar 2024 | Russian Field | 66% | 5% | 4% | 6% | 0.4% | 5% | 14% | ||

| 2–3 Mar 2024 | VCIOM | 60% | 3% | 2% | 5% | 2% | 17% | 11% | ||

| 10–18 Feb 2024 | CIPKR | 62% | 6% | 3% | 4% | 7% | 5% | 13% | ||

| 16 Feb 2024 | Alexei Navalny dies while serving a 19-year prison sentence | |||||||||

| 15 February 2024 | VCIOM | 61% | Rejected | 3% | 2% | 3% | 2% | 17% | 13% | |

| 14 February 2024 | VCIOM | 64% | 4% | 3% | 5% | 2% | 2% | 2% | ||

| 9-11 Feb 2024 | FOM | 74% | 3% | 3% | 2% | 1% | 10% | 5% | ||

| 8 February 2024 | VCIOM | 57% | 3% | 3% | 4% | 2% | 18% | 14% | ||

| 8 Feb 2024 | Central Election Commission bars Nadezhdin from participating in the elections | |||||||||

| 1–7 Feb 2024 | ExtremeScan | 63% | 6% | — | — | — | 8% | 12% | 11% | |

| 27–30 Jan 2024 | Russian Field | 62.2% | 7.8% | 2.3% | 1.9% | 1.0% | 2.5% | 7.8% | 12.8% | |

| 25–30 Jan 2024 | ExtremeScan | 61% | 6% | 2% | 1% | — | 2% | 17% | 11% | |

| 11–28 Jan 2024 | CIPKR | 60% | 7% | 4% | 3% | 0.3% | 3% | 7% | 15% | |

| Fieldwork date | Polling firm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others | Undecided | Abstention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Putin | Grudinin | Zyuganov | Slutsky | Shoigu | Lavrov | Medvedev | Sobyanin | Dyumin | Volodin | Mishustin | Platoshkin | Bondarenko | Mironov | |||||||||

| Dec 2023 | VCIOM | 42.7% | 1.6% | 3.8% | Deceased | — | 1.2% | 8.7% | 14.3% | — | — | — | 2.9% | 18.8% | — | 0.7% | 0.8% | 1.8% | Deceased | 1.2% | 37.2% | |

| Nov 2023 | VCIOM | 37.3% | 1.4% | 3.0% | — | 1.3% | 8% | 15.4% | — | — | — | 2.7% | 16.6% | — | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.7% | 1.3% | 42% | |||

| 23–29 Nov 2023 | Levada Center | 58.0% | 0.5% | 1.3% | 0.5% | — | — | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.3% | — | — | 0.5% | — | — | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.8% | 31.9% | 4.8% | ||

| Oct 2023 | VCIOM | 37.3% | 1.7% | 3.0% | — | 1.4% | 7.2% | 15.3% | — | — | — | 3.1% | 15.6% | — | 0.7% | 0.9% | 1.6% | 1.7% | 42.2% | |||

| Sep 2023 | VCIOM | 36% | 1.4% | 3.6% | — | 1.8% | 7.3% | 14.7% | — | — | — | 2.7% | 15.3% | — | 0.7% | 0.9% | 1.7% | 1.8% | 42.9% | |||

| 2–10 Sep 2023 | Russian Field | 29.9% | 1.3% | 0.6% | — | 1.7% | 0.5% | 0.6% | — | 0.6% | — | — | 1.1% | — | 0.6% | — | — | 23.6% | 32.2% | 6.4% | ||

| Aug 2023 | VCIOM | 35.5% | 1.5% | 3.4% | — | 1.7% | 7.1% | 12.6% | — | — | — | 3.2% | 15.4% | — | 0.7% | 0.7% | 1.7% | 1.7% | 43.9% | |||

| 23 Aug 2023 | Wagner Group plane crash including leader Yevgeny Prigozhin died in a crash | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1–9 Aug 2023 | CIPKR | 60% | 4% | 2% | Deceased | 4% | 2% | — | 1% | — | — | 3% | — | — | — | — | 11% | 7% | 3% | |||

| Jul 2023 | VCIOM | 37.1% | 1.3% | 3.2% | — | 1.5% | 6.9% | 13.9% | — | — | — | 3.0% | 16.8% | — | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.7% | — | 2.0% | 42.1% | ||

| 20–26 Jul 2023 | Levada Center | 44% | — | 3% | 1% | 7% | 13% | 3% | 4% | — | 18% | — | — | — | — | 7% | 19% | 5.9% | ||||

| Jun 2023 | VCIOM | 37.1% | 1.4% | 3.4% | — | 1.7% | 8.9% | 14.1% | 3.4% | 15.5% | — | 0.8% | 0.5% | 1.7% | 1.9% | 41.4% | ||||||

| 22–28 Jun 2023 | Levada Center | 42% | — | 4% | — | 8% | 14% | 4% | 4% | — | 18% | — | — | — | 2% | 5% | ||||||

| 23–24 Jun 2023 | Wagner Group rebellion | |||||||||||||||||||||

| May 2023 | VCIOM | 37.1% | 1.2% | 3.9% | Deceased | — | 1.3% | 10.0% | 14.7% | 3.2% | 15.5% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 2.0% | 1.7% | 41.2% | ||||||

| 13–16 May 2023 | Russian Field | 30.2% | 1.1% | — | 2.8% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.8% | — | 0.4% | 1.1% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 3% | 26.4% | 28.8% | 5.9% | ||||

| Apr 2023 | VCIOM | 38.7% | 1.4% | 3.6% | — | 1.2% | 12.1% | 17.6% | 2.8% | 16.5% | 0.9% | 0.8% | 2.3% | 1.7% | 39.3% | |||||||

| Mar 2023 | VCIOM | 38.7% | 1.3% | 3.7% | — | 1.6% | 11.5% | 16.3% | 3.2% | 17.4% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 2.2% | 2.2% | 39.6% | |||||||

| Feb 2023 | VCIOM | 37.5% | 1.4% | 4.4% | — | 1.8% | 11.2% | 16.3% | 3.2% | 14.3% | 0.9% | 0.8% | 2.6% | 2.0% | 39.8% | |||||||

| 21–28 Feb 2023 | Levada Center | 43% | 1% | 5% | 1% | 12% | 15% | 3% | 3% | — | 17% | 1% | — | — | — | 6% | 17% | 16% | ||||

| Jan 2023 | VCIOM | 37.1% | 1.5% | 3.2% | — | 1.9% | 13.4% | 15.2% | 4.1% | 14.9% | 1.0% | 0.9% | 1.8% | 2.4% | 40.1% | |||||||

| 24–30 Nov 2022 | Levada Center | 39% | — | 5% | 1% | 12% | 14% | 3% | 3% | — | 17% | — | — | 1% | — | 5% | 7% | 18% | ||||

| 30 Sep 2022 | Russia annexes part of southeastern Ukraine | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 21–27 Jul 2022 | Levada Center | 43% | — | 4% | Deceased | 1% | 14% | 14% | 3% | 4% | — | 16% | — | — | 1% | — | 5% | 16% | 16% | |||

| 6 Apr 2022 | Liberal Democratic Party of Russia leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky dies[117] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 Feb 2022 | Beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 Feb 2022 | Russia announces international recognition of the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 10–28 Dec 2021 | CIPKR | — | 3% | — | 0% | 5% | 18% | — | 2% | 1% | 1% | 15% | — | — | — | — | 24% | 31% | ||||

| 25 Nov–1 Dec 2021 | Levada Center | 32% | 1% | 2% | 3% | 1% | 1% | — | — | — | — | 1% | — | — | 1% | — | 3% | 21% | 27% | |||

| 22–28 Apr 2021 | Levada Center | 40% | 1% | 2% | 4% | 2% | — | — | — | — | — | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | — | 3% | 18% | 23% | |||

| 17 Jan 2021 | Arrest of Alexei Navalny | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dec 2020 | CIPKR | — | 5% | — | 1% | 2% | 18% | — | 4% | 2% | 0% | 8% | — | — | — | – | 33% | 27% | ||||

| 19–26 Nov 2020 | Levada Center | 39% | 1% | 2% | 6% | 2% | 1% | — | — | — | — | 1% | — | 1% | — | — | 2% | 16% | 24% | |||

| 20–26 Aug 2020 | Levada Center | 40% | 1% | 1% | 4% | 2% | 1% | — | — | — | — | 1% | 1% | 1% | — | — | 2% | 26% | 22% | |||

| 9 Jul 2020 | Arrest of Sergei Furgal | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 18–23 Dec 2019 | CIPKR | — | 9% | — | 4% | — | 24% | — | 11% | 5% | 1% | — | — | — | — | – | 26% | 20% | ||||

| 12–18 Dec 2019 | Levada Center | 38% | 3% | 2% | 4% | 2% | 1% | — | 1% | — | — | — | — | — | — | – | 2% | 26% | 22% | |||

| 18–24 Jul 2019 | Levada Center | 40% | 3% | 1% | 3% | 1% | — | — | <1% | — | — | — | — | — | — | – | 2% | 31% | 19% | |||

| 21–27 Mar 2019 | Levada Center | 41% | 4% | 2% | 5% | 1% | 1% | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | – | 3% | 26% | 19% | |||

| 18–24 Oct 2018 | Levada Center | 40% | 3% | 2% | 4% | 1% | <1% | <1% | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | – | 2% | 27% | 23% | |||

Exit polling

[edit]Exit polls on 17 March released by the Russian Public Opinion Research Center showed Vladimir Putin with 87% of the vote, 10% more than in 2018, Nikolai Kharitonov with 4.6%, Vladislav Davankov with 4.2% and Leonid Slutsky with 3%. Invalid ballots accounted for 1.2% of votes cast.[118]

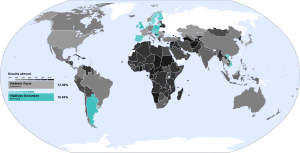

Overseas

[edit]

The CEC said that 388,791 Russians cast their ballots from abroad.[119]

In contrast to the official exit polls and results of the election both inside and outside of Russia, unofficial exit polls of the votes cast abroad showed a much poorer performance for Putin. According to the Vote Abroad project,[120] Davankov won a plurality of the votes at most of the voting stations abroad, earning his best result in Trabzon. However, Putin secured pluralities in Genoa, Rome, Nicosia, Chișinău, Ankara, Samarkand and Bonn. He also won 59% in Athens, making it his best performance abroad.[121] Conversely, he got his worst showing in The Hague, with just 2% of the vote.[122] Putin won 3% in Poland, Serbia and Montenegro, and 8% in Almaty, Kazakhstan.[123]

According to the Vote Abroad project, Putin was also voted for by 4% of Russians living in Lithuania and the Czech Republic, 5% in Istanbul, Turkey, 6% in Argentina and the United Kingdom, 7% in Austria, Ireland and Slovakia, 8% in Estonia, Denmark and Yerevan, Armenia, 9% in Portugal, 10% in Thailand, Finland and Berlin, Germany, 11% in Madrid, Spain and Paris, France, 13% in Norway, 14% in Sweden and Hungary, 15% in Vietnam and the United States, 16% in Tel Aviv, Israel and Bern, Switzerland, 17% in Japan, 22% in Cyprus, 23% in Milan, Italy, 31% in Dubai, 35% in Chișinău, Moldova and Uzbekistan, 36% in Kyrgyzstan and 38% in Rome, Italy.[120] In total, exit polls organized by exiled Russian activists across 44 countries showed Davankov gaining more votes than Putin in all but five countries.[124]

The election was also held in Moldova's Transnistria, an internationally unrecognized state. 46,179 people with Russian citizenship voted in the election, the lowest turnout in a Russian presidential election in the last 18 years. 97% voted for Putin, with the other three candidates not having even obtained 1,000 votes combined.[125] According to TRT Russian, the low turnout indicated changes in the political activity of Transnistrians with Russian citizenship, with over 73,000 having participated in the last election six years ago. Furthermore, it stated Moldovan analysts believed the low turnout indicated a trend that Transnistria was moving away from Russia and that Moldovan President Maia Sandu's pro-European policy was influencing the region.[126]

Election observers

[edit]The domestic watchdog Golos, having been previously labelled a "foreign agent" in 2013 after documenting fraud in the 2011 parliamentary vote and the 2012 presidential election, was not allowed to send election observers. [127][128]

On 29 January 2024, the OSCE's Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) announced that the organisation would not participate in international monitoring of election, citing the lack of an invitation from Russia.[129]

On 17 March 2024, the Chair of the Central Election Commission of the Russian Federation (CEC), Ella Pamfilova, announced that 1,115 international observers and experts from 129 countries were monitoring the electoral process.[130]

Results

[edit]

Kharitonov Davankov Slutsky

| Candidate | Party | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vladimir Putin | Independent[e] | 76,277,708 | 88.48 | |

| Nikolay Kharitonov | Communist Party | 3,768,470 | 4.37 | |

| Vladislav Davankov | New People | 3,362,484 | 3.90 | |

| Leonid Slutsky | Liberal Democratic Party | 2,795,629 | 3.24 | |

| Total | 86,204,291 | 100.00 | ||

| Valid votes | 86,204,291 | 98.43 | ||

| Invalid/blank votes | 1,371,784 | 1.57 | ||

| Total votes | 87,576,075 | 100.00 | ||

| Registered voters/turnout | 113,011,059 | 77.49 | ||

| Source: CEC, Rapsi News, Bezformata | ||||

On 21 March, the CEC officially announced that Vladimir Putin had won the election, receiving 87.28% of all votes cast (including invalid ballots), followed by Nikolai Kharitonov with 4.31% of the vote, Vladislav Davankov with 3.85% and Leonid Slutsky with 3.20%.[119]

Results by federal subject

[edit]

| Region | Putin | Kharitonov | Davankov | Slutsky |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adygea | 90.18% | 3.68% | 2.20% | 2.70% |

| Altai Krai | 84.88% | 5.41% | 4.58% | 3.63% |

| Altai Republic | 86.49% | 5.63% | 3.43% | 2.73% |

| Amur Oblast | 86.97% | 3.94% | 3.66% | 3.69% |

| Arkhangelsk Oblast | 79.25% | 5.31% | 7.60% | 5.93% |

| Astrakhan Oblast | 87.45% | 5.39% | 3.72% | 2.31% |

| Bashkortostan | 90.90% | 3.69% | 2.72% | 1.88% |

| Belgorod Oblast | 90.66% | 3.59% | 2.36% | 2.50% |

| Bryansk Oblast | 89.97% | 4.25% | 1.44% | 3.62% |

| Buryatia | 87.96% | 4.32% | 3.71% | 2.38% |

| Chechnya | 98.99% | 0.29% | 0.15% | 0.50% |

| Chelyabinsk Oblast | 84.32% | 5.40% | 4.90% | 3.49% |

| Chukotka | 90.49% | 2.30% | 2.92% | 3.03% |

| Chuvashia | 85.49% | 5.35% | 4.70% | 3.01% |

| Dagestan | 92.93% | 3.97% | 0.73% | 1.80% |

| Donetsk People's Republic* | 95.23% | 1.62% | 1.33% | 1.53% |

| Ingushetia | 89.61% | 3.72% | 2.45% | 2.83% |

| Irkutsk Oblast | 84.65% | 4.96% | 4.53% | 4.79% |

| Ivanovo Oblast | 86.88% | 4.66% | 3.66% | 3.24% |

| Jewish Autonomous Oblast | 92.35% | 3.17% | 1.39% | 2.03% |

| Kabardino-Balkaria | 94.21% | 2.45% | 1.12% | 2.12% |

| Kaliningrad Oblast | 85.44% | 3.62% | 5.86% | 3.13% |

| Kalmykia | 87.17% | 7.70% | 2.06% | 2.13% |

| Kaluga Oblast | 83.79% | 5.00% | 5.74% | 3.48% |

| Kamchatka Krai | 85.03% | 4.12% | 4.86% | 4.29% |

| Karachay-Cherkessia | 90.07% | 5.11% | 1.04% | 2.92% |

| Karelia | 79.53% | 4.76% | 8.38% | 5.02% |

| Kemerovo Oblast | 95.72% | 1.36% | 1.00% | 1.13% |

| Khabarovsk Krai | 80.06% | 5.43% | 6.63% | 5.01% |

| Khakassia | 85.28% | 5.84% | 4.01% | 3.03% |

| Khanty–Mansi | 86.71% | 5.56% | 2.45% | 4.43% |

| Kherson Oblast* | 88.12% | 4.88% | 2.03% | 4.60% |

| Kirov Oblast | 80.08% | 5.56% | 6.65% | 5.41% |

| Komi Republic | 80.49% | 5.38% | 6.45% | 5.08% |

| Kostroma Oblast | 80.52% | 6.49% | 6.09% | 4.69% |

| Krasnodar Krai | 92.59% | 3.42% | 1.38% | 2.01% |

| Krasnoyarsk Krai | 84.12% | 4.35% | 5.46% | 3.98% |

| Kurgan Oblast | 85.63% | 5.01% | 3.82% | 3.99% |

| Kursk Oblast | 88.51% | 3.62% | 3.80% | 2.78% |

| Leningrad Oblast | 86.36% | 4.78% | 3.99% | 2.95% |

| Lipetsk Oblast | 86.99% | 4.72% | 4.04% | 2.88% |

| Lugansk People's Republic* | 94.12% | 1.91% | 1.39% | 2.13% |

| Magadan Oblast | 84.89% | 4.38% | 4.73% | 3.85% |

| Mari El | 84.24% | 6.11% | 4.72% | 3.36% |

| Mordovia | 89.57% | 4.22% | 2.38% | 3.00% |

| Moscow | 85.13% | 3.84% | 6.65% | 2.38% |

| Moscow Oblast | 86.50% | 5.09% | 4.21% | 3.04% |

| Murmansk Oblast | 83.21% | 4.03% | 6.67% | 4.16% |

| Nenets | 79.08% | 6.86% | 6.46% | 5.84% |

| Nizhny Novgorod Oblast | 86.40% | 5.47% | 3.75% | 3.32% |

| North Ossetia–Alania | 89.01% | 5.10% | 1.70% | 3.50% |

| Novgorod Oblast | 82.06% | 5.21% | 6.22% | 4.28% |

| Novosibirsk Oblast | 83.88% | 4.60% | 6.40% | 3.06% |

| Omsk Oblast | 82.77% | 5.71% | 5.67% | 3.32% |

| Orenburg Oblast | 87.05% | 5.06% | 3.44% | 2.80% |

| Oryol Oblast | 80.23% | 9.14% | 4.35% | 4.25% |

| Penza Oblast | 89.97% | 4.05% | 2.51% | 2.33% |

| Perm Krai | 84.65% | 4.96% | 4.53% | 4.79% |

| Primorsky Krai | 88.34% | 3.35% | 2.72% | 4.07% |

| Pskov Oblast | 84.70% | 5.29% | 5.23% | 3.48% |

| Republic of Crimea* | 93.60% | 2.08% | 1.94% | 1.30% |

| Rostov Oblast | 90.81% | 3.65% | 2.76% | 2.07% |

| Ryazan Oblast | 89.93% | 4.29% | 3.76% | 2.65% |

| Saint Petersburg | 81.65% | 3.49% | 6.99% | 5.15% |

| Sakha (Yakutia) | 87.79% | 4.32% | 4.73% | 1.76% |

| Sakhalin Oblast | 86.37% | 4.61% | 3.85% | 3.25% |

| Samara Oblast | 86.76% | 4.36% | 4.18% | 3.07% |

| Saratov Oblast | 91.66% | 4.78% | 1.18% | 1.75% |

| Sevastopol* | 92.60% | 2.07% | 2.88% | 1.54% |

| Smolensk Oblast | 84.65% | 5.08% | 4.75% | 3.25% |

| Stavropol Krai | 88.56% | 3.99% | 1.51% | 5.37% |

| Sverdlovsk Oblast | 82.10% | 4.23% | 7.31% | 3.91% |

| Tambov Oblast | 85.59% | 6.43% | 3.08% | 3.77% |

| Tatarstan | 88.74% | 4.83% | 1.53% | 3.93% |

| Tomsk Oblast | 82.15% | 4.39% | 7.48% | 3.62% |

| Tula Oblast | 87.29% | 4.89% | 3.50% | 2.87% |

| Tuva | 95.37% | 2.10% | 1.07% | 1.14% |

| Tver Oblast | 84.38% | 4.80% | 5.28% | 3.59% |

| Tyumen Oblast | 84.76% | 6.17% | 2.03% | 6.27% |

| Udmurtia | 81.83% | 5.42% | 6.16% | 4.23% |

| Ulyanovsk Oblast | 83.85% | 5.81% | 4.71% | 3.62% |

| Vladimir Oblast | 84.93% | 4.68% | 4.88% | 3.79% |

| Volgograd Oblast | 88.00% | 6.63% | 1.13% | 3.72% |

| Vologda Oblast | 79.74% | 5.66% | 7.01% | 5.77% |

| Voronezh Oblast | 88.83% | 3.73% | 3.95% | 2.39% |

| Yamalo-Nenets | 91.75% | 2.51% | 1.60% | 3.37% |

| Yaroslavl Oblast | 80.84% | 5.38% | 7.39% | 4.46% |

| Zabaykalsky Krai | 87.71% | 3.99% | 3.26% | 3.32% |

| Zaporozhye Oblast* | 92.83% | 2.21% | 1.87% | 2.52% |

Reactions

[edit]Domestic

[edit]

On 6 August 2023, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov told The New York Times that "our presidential election is not really democracy, it is costly bureaucracy. Mr. Putin will be re-elected next year with more than 90 percent of the vote". Later he clarified that this was his personal opinion.[132] In an interview with the RBK news agency, Peskov said that Russia "theoretically" does not need to hold presidential elections because "it's obvious that Putin will be reelected."[133]

On 6 November 2023, journalist Yekaterina Duntsova announced her intention to run for the presidency in the 2024 election; she said she would run as an independent candidate on an anti-war platform.[134] The next month, her nomination documents were rejected by the Central Election Commission.[135]

In November 2023, nationalist ex-militia commander Igor Girkin announced his intention to run as a candidate in the 2024 elections, describing elections in Russia as a "sham" in which "the only winner [referring to Putin] is known in advance".[136]

In January 2024, citing unidentified sources in the Kremlin, the independent news outlet Vyorstka reported that the CEC, at the behest of the Kremlin, will likely reject Boris Nadezhdin's registration due to his criticism of Putin and anti-war stances.[137] In late January 2024, a source in the Putin administration told the Latvia-based news outlet Meduza: "There's a portion of the electorate that wants the war to end. If [Putin's opponent in the elections] decides to cater to this demand, they may get a decent percentage. And [the Putin administration] doesn't need that."[138] Russian state media intensified a smear campaign against Nadezhdin in the weeks leading up to the election. On 30 January 2024, Kremlin propagandist and television presenter Vladimir Solovyov warned Nadezhdin: "I feel bad for Boris. The fool didn't realize that he's not being set up to run for president but for a criminal case on charges of betraying the Motherland."[138]

Following the CEC's decision to ban him from running, Nadezhdin wrote in his Telegram channel: "I do not agree with the decision of the CEC... Participating in the presidential election in 2024 is the most important political decision in my life. I am not backing down from my intentions."[139]

Prior to the release of official results, former president and deputy head of the Security Council of Russia Dmitry Medvedev congratulated Putin on his "splendid victory".[140] After his victory was confirmed, Putin held a news conference on 18 March calling his win a vindication of his policy of defying the West and his decision to invade Ukraine.[4] He also described the result as an indication of "trust" and "hope" in him.[98] Exiled Russian dissident Leonid Volkov said that Putin's percentage of victory had "not the slightest relation to reality".[141]

International

[edit]In an interview with TV3 on 4 March 2024, Latvian justice minister Inese Lībiņa-Egnere implied that Russians in the country who would participate in the election to be held in the Russian embassy in Riga could face criminal liability for justifying the invasion of Ukraine under Latvian law.[142] On 14 March, Lībiņa-Egnere appeared to have reversed her stance, stating that participation in the elections "does not equate to supporting Putin" and is "not punishable in any way"; she added that Latvia "does not want to provoke an international row and intends to act like a democratic state".[143] On 11 March, Armands Ruks, the head of the Latvian State Police announced that voters at the embassy would be subjected to police screenings before entering.[144]

The Russian ambassador to Moldova, Oleg Vasnetsov, was summoned to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Moldova on 12 March following Russia's decision to open six polling stations in Transnistria for the election, which Moldovan foreign minister Mihai Popșoi described as "unacceptable". The Moldovan government had previously agreed to open only one polling station in the Russian embassy in Chișinău as per international law as it claimed.[145] Russia's opening of polling stations in Transnistria was also condemned by Romania, the United States[146] and France.[147] On 19 March, Popșoi announced the expulsion of a Russian diplomat in response to the holding of elections in Transnistria.[148]

The Ukrainian foreign ministry called on international media and public figures "to refrain from referring to this farce as 'elections' in the language of democratic states."[149] The United States condemned voting in Russian-occupied areas of Ukraine, with State Department Spokesperson Matthew Miller saying that the US would "never recognize the legitimacy or outcome of these sham elections held in sovereign Ukraine".[149] On 15 March, Ukraine's ambassador to the United Nations, Sergiy Kyslytsya, released a joint statement on behalf of Ukraine, the European Union and 56 other countries including the US condemning the holding of the elections in occupied parts of the country.[150] The Ukrainian government said it would not press charges against its residents of occupied areas who participate in the election, saying that they were being forced to vote.[151] The UN Security Council condemned the holding of the elections in occupied territories of Ukraine with deputy secretary-general Rosemary DiCarlo saying that "holding elections in another UN member state's territory without its consent is in manifest disregard for the principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity" and were "invalid" under international law.[152]

On the first day of regular voting on 15 March, European Council president Charles Michel sarcastically congratulated Putin for winning a "landslide victory" in the elections starting that day, adding that there was "No opposition. No freedom. No choice."[112] On 18 March, the European Union condemned "the illegal holding of so-called elections' in the territories of Ukraine" and said it would never recognise them. The EU's foreign policy chief Josep Borrell added that the election was held in the context of a shrinking political space.[153]

Following the release of the results, Germany described the vote as a "pseudo-election" under an authoritarian ruler reliant on censorship, repression and violence.[154] The UK's Foreign Secretary, David Cameron condemned "the illegal holding of elections on Ukrainian territory",[154] adding that the vote was "not what free and fair elections look like". A spokesperson for the United States National Security Council described the election as "obviously not free nor fair given how Mr. Putin has imprisoned political opponents and prevented others from running against him",[4] but said that the US would recognize Putin as president.[155] In his evening address on 17 March, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy described the election as an "imitation" with "no legitimacy", adding that Putin was "addicted to power and does everything he can to rule forever" and that "There is no evil he will not commit to prolong his personal power."[156] Italian foreign minister Antonio Tajani described the election as "neither free nor fair", while Czech foreign minister Jan Lipavský called the election a "farce and parody".[157] Lithuanian foreign minister Gabrielius Landsbergis called the voting a "procedure that is supposed to resemble elections", adding that "Some might call it reappointment, lacking any legitimacy."[158] The French foreign ministry said the "conditions for a free, pluralist and democratic election were not met", but praised "the courage of the many Russian citizens who have peacefully demonstrated their opposition to this attack on their fundamental political rights."[159] South Korea refrained from commenting on the election and said that "it would make considerations of 'appropriateness' in regard to a possible congratulatory cable to Putin."[160]

Leaders of countries with neutral or friendly relations with Russia sent congratulations to Putin on his victory,[f] along with President of Republika Srpska Milorad Dodik, members of the Moldovan opposition, and Hamas political chairman Ismail Haniyeh.[206][207] Presidents Aslan Bzhania and Alan Gagloev, of the pro-Russian breakaway states of Abkhazia and South Ossetia respectively, also congratulated Putin.[208][209]

Protests

[edit]

On 1 February 2024, jailed Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny and his allies called on supporters to protest Putin and the invasion of Ukraine on the last day of the election on 17 March all going to vote against Putin at the same time.[210] Following Navalny's death on 16 February, there were calls from Andrius Kubilius, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, and Navalny's widow, Yulia Navalnaya for the EU to recognize the Russian elections as illegitimate.[211][212][213] Navalnaya called for Russians critical of Putin to join the "Noon Against Putin" initiative to form long queues at polling stations at noon on 17 March before proceeding to vote for anyone other than Putin, spoil their ballots or cast Navalny's name.[214] On the day of the action, Navalnaya joined queues outside the Russian embassy in Berlin[215] for about six hours before casting her vote for her husband and praising protesters for giving her "hope that everything is not in vain".[154] In Russia, queues formed at polling stations in Moscow and Saint Petersburg at noon.[216] Queues were also observed outside Russian diplomatic missions worldwide, including in Belgrade, London, Podgorica, Tallinn, Paris and Milan.[114][154][217][218]

In response to the protests, authorities in Moscow threatened to prosecute participants under Article 141 of the Criminal Code of Russia, which prescribes five years' imprisonment for the obstruction of elections or citizens' electoral rights.[219] On 17 March, the Russian human rights group OVD-Info said that 80 people in 20 cities across Russia were arrested for election-related offences.[140] In response to the Noon Against Putin protests abroad, foreign ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova described the queues outside Russian embassies as evidence of support for the Kremlin.[220]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Early voting had taken place from 26 February in several remote regions of the Russian Far East as well as occupied territories of Ukraine.[3]

- ^ Putin has strong ties with United Russia and ran as its candidate in 2012.

- ^ The case deals with CEC's refusal to register Nadezhdin as a candidate for the election and seeks his direct reinstating.

- ^ The two cases are concerned on CEC's apparent procedural faults while checking the selected signatures. If both cases were upheld, Nadezhdin would have enough valid signatures to be reinstated as a candidate.

- ^ Supported by the People's Front, United Russia, A Just Russia – For Truth, Rodina, Russian Party of Pensioners for Social Justice, Party of Business, Russian All-People's Union and Democratic Party of Russia

- ^ Algeria,[161] Armenia,[162] Azerbaijan,[163] Bahrain,[164] Bangladesh,[165] Belarus,[158] Bolivia,[166] Brazil,[167] Burkina Faso,[168] Burundi,[169] Cambodia,[170] the Central African Republic,[171] Chad,[168] China,[172] the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[173] the Republic of the Congo,[174] Cuba,[175] Egypt,[176] Guinea-Bissau,[177] Eritrea,[178] Honduras,[179] Hungary,[180] India,[181] Iran,[182] Kazakhstan,[183] North Korea,[172] Kuwait,[164] Kyrgyzstan,[184] Laos,[185] Libya,[186] Mali,[187] Morocco,[188] Myanmar,[189] Nicaragua,[190] Niger,[168] Oman,[164] Pakistan,[191] Palestine,[192] Qatar,[164] the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic,[193] Saudi Arabia,[164] Serbia,[194] South Africa,[195] Syria,[196] Tajikistan,[197] Tanzania,[198] Turkey,[199] Turkmenistan,[200] the United Arab Emirates,[164] Uzbekistan,[201] Venezuela,[202] Vietnam,[203] Yemen,[204] and Zimbabwe[205]

References

[edit]- ^ "Russian presidential election set for March 15–17, 2024". Meduza. Archived from the original on 12 December 2023. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ "Совет Федерации назначил выборы президента РФ на 17 марта". Interfax (in Russian). 7 December 2023. Archived from the original on 7 December 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ "In Photos: Residents of Remote Areas Start Voting in Russia's Presidential Election". 29 February 2024. Archived from the original on 4 March 2024. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Russia's Putin hails victory in election criticised as illegitimate". Al Jazeera. 18 March 2024. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Headley, James (18 March 2024). "Putin landslide surprises nobody – but what comes next?". MSN. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Kastouéva-Jean, Tatiana (16 March 2024). "'Russia's presidential election is about Putin convincing himself and others that he has mastered all the workings of the system'". Le Monde.fr. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "Федеральный закон от 10.01.2003 N 19-ФЗ (ред. от 05.12.2017) "О выборах Президента Российской Федерации" Статья 82. Вступление в должность Президента Российской Федерации". Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ Документы в ЦИК представили шесть самовыдвиженцев и девять кандидатов от партий. Новости. Первый канал (in Russian), archived from the original on 28 December 2023, retrieved 29 December 2023

- ^ "Экс-депутат Госдумы с антивоенными взглядами планирует стать кандидатом в президенты России". RTVI. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 27 November 2023 – via VK.

- ^ "Выборы не за горами". Kommersant (in Russian). 13 January 2023. Archived from the original on 5 December 2023. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- ^ "Песков: в Кремле пока не готовятся к выборам президента". Kommersant (in Russian). 23 January 2023. Archived from the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "Russia's Putin says he will run for president again in 2024 – TASS". Reuters. 8 December 2023. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Alexei Navalny, Russia's most vociferous Putin critic". BBC News. 16 February 2024. Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ "Who was Alexei Navalny and what did he say of Russia, Putin and death?". Reuters. 17 February 2024. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Neil; Nechepurenko, Ivan (8 February 2017). "Aleksei Navalny, Viable Putin Rival, Is Barred From a Presidential Run". New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Gomozova, Tatiana; Osborn, Andrew; Osborn, Andrew (5 August 2023). "Putin critic Alexei Navalny has 19 years added to jail term, West condemns Russia". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ Bennetts, Marc (26 December 2017). "Russia rejects concerns over banning of Alexei Navalny from elections". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 October 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Lenton, Adam (12 March 2024). "3 things to watch for in Russia's presidential election – other than Putin's win, that is". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "US weighs response to Navalny's reported death". ABC News. 16 February 2024. Archived from the original on 25 February 2024. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ Tenisheva, Anastasia (8 February 2024). "Russian Election Authority Rejects Pro-Peace Hopeful Nadezhdin's Presidential Bid". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "Presidential candidate Davankov's manifesto calls for 'peace and negotiations'". Novaya Gazeta Europe. 15 February 2024. Archived from the original on 18 February 2024. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ a b Christian Edwards, Putin extends one-man rule in Russia after stage-managed election devoid of credible opposition Archived 18 March 2024 at the Wayback Machine, CNN (18 March 2024).

- ^ Francesca Ebel, Putin, claiming Russian voters are with him, vows to continue war, Washington Post (18 March 2024).

- ^ "Alexei Navalny: Widow urges Russians to protest on election day". BBC News. 6 March 2024. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ Roth, Andrew; Sauer, Pjotr (15 March 2024). "A forever war, more repression, Putin for life? Russia's bleak post-election outlook". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Putin Wins 87.28% of Votes With All Ballots Counted – Election Officials". The Moscow Times. 18 March 2024. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ Robyn Dixon, Siobhán O'Grady, David L. Stern, Serhii Korolchuk and Serhiy Morgunov, For Putin's election in occupied Ukraine, voting is forced at gunpoint Archived 17 March 2024 at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post; (16 March 2024).

- ^ a b Emma Burrows (16 March 2024). "Russians cast ballots on Day 2 of an election preordained to extend President Vladimir Putin's rule". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Ukrainians living under Russian occupation are coerced to vote for Putin". Associated Press. 14 March 2024. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Putin 2024 - Meduza breaks down the evidence pointing to the most fraudulent elections in modern Russian history". Meduza. 20 March 2024. Wikidata Q125025516. Archived from the original on 20 March 2024.

- ^ "Constitution of Russia. Chapter 4. The President of the Russian Federation. Article 81". Constitution. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "Vladimir Putin passes law that may keep him in office until 2036". The Guardian. 5 April 2021. Archived from the original on 17 February 2024. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ "Статья 81 Конституция Российской Федерации (принята на всенародном голосовании 12 декабря 1993 г.) (с поправками)". Garant. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ "Знать четырех". Kommersant (in Russian). 9 February 2024. Archived from the original on 10 February 2024. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ "Что известно о Владиславе Даванкове" [What is known about Vladislav Davankov]. Tass. Archived from the original on 24 December 2023. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ Колесник, Вероника (25 December 2023). "Даванков подал документы в ЦИК для участия в выборах президента от "Новых людей"". Izvestia (in Russian). Archived from the original on 25 December 2023. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ "ЦИК зарегистрировал группу избирателей в поддержку Путина". RIA Novosti (in Russian). 20 December 2023. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "Путин подал документы для участия в выборах президента". Kommersant (in Russian). 18 December 2023. Archived from the original on 18 December 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ "ЦИК зарегистрировал Путина кандидатом на выборы президента России". Kommersant (in Russian). 29 January 2024. Archived from the original on 29 January 2024. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ a b c "ЛДПР выдвинула Слуцкого кандидатом в президенты России". Ведомости (in Russian). Archived from the original on 19 December 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Слуцкий подал документы в ЦИК для участия в выборах президента". Tass. Archived from the original on 25 December 2023. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ "Документы в ЦИК представили шесть самовыдвиженцев и девять кандидатов от партий" [Six self-nominated candidates and nine party candidates submitted documents to the CEC], Channel One Russia (in Russian), archived from the original on 28 December 2023, retrieved 29 December 2023

- ^ "Правила регистрации кандидатов-самовыдвиженцев на выборах президента РФ". Tass. Archived from the original on 18 December 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ "В РФ собрали более 500 тыс. подписей в поддержку самовыдвижения Путина на выборах". Tass. Archived from the original on 31 December 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ "Штаб Путина собрал более 2,5 млн подписей в поддержку его выдвижения". Kommersant (in Russian). 17 January 2024. Archived from the original on 17 January 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ "Лидер партии "Коммунисты России", депутат Алтайского краевого законодательного собрания Сергей Малинкович подал..." Novosti Zhytomyr (in Russian). 1 January 2024. Archived from the original on 1 January 2024. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ "Три кандидата собрали подписи для участия в президентских выборах". Ведомости (in Russian). Archived from the original on 25 January 2024. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ a b "ЦИК не зарегистрировал Бориса Надеждина кандидатом в президенты". Kommersant (in Russian). 8 February 2024. Archived from the original on 8 February 2024. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ "В РФ появился первый кандидат на пост президента". URA (in Russian). 31 October 2023. Archived from the original on 1 November 2023. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ "Надеждин подал документы в ЦИК для участия в выборах президента". RIA Novosti (in Russian). 26 December 2023. Archived from the original on 26 December 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ "ЦИК нашел в подписях за Надеждина более 5% допустимого брака" [The CEC found more than 5% of acceptable invalid signatures in the signatures in favour of Nadezhdin]. Kommersant (in Russian). 8 February 2024. Archived from the original on 8 February 2024. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ "Official site". Archived from the original on 31 January 2024. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "Иски в Верховный Суд РФ (Official Site)". Archived from the original on 23 February 2024. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ "Съезд "ЕР" единогласно поддержал кандидатуру Путина на выборах президента". www.mk.ru (in Russian). 17 December 2023. Archived from the original on 17 December 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ Dariya Garmonenko (14 November 2023). "Надеждин с кем-нибудь разделит ненужные власти голоса". Nezavisimaya Gazeta. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ "КПРФ определилась с кандидатом: главные итоги съезда коммунистов". FederalPress (in Russian). 23 December 2023. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Нажбудинова, Амалия (23 December 2023). "Миронов поддержал Путина в качестве кандидата на выборах президента России". Izvestia (in Russian). Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Лидер партии Социальной защиты Михайлов подал документы в ЦИК". 24 December 2023. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ "Партия РОС определилась с кандидатом на выборах президента РФ – Газета.Ru | Новости". Gazeta (in Russian). 23 December 2023. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Бабурин снялся с выборов президента". Kommersant (in Russian). 30 January 2024. Archived from the original on 30 January 2024. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ "Партия роста присоединится к "Новым людям"". Ведомости (in Russian). Archived from the original on 24 December 2023. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ ""Новые люди" проведут предвыборный съезд 24 декабря". RIA Novosti. 29 November 2023. Archived from the original on 1 December 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ Анасьева, Ольга (24 December 2023). "Политика Богданова выдвинули кандидатом на выборах президента от РПСС". Izvestia (in Russian). Archived from the original on 25 December 2023. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ Елизавета КУЗНЕЦОВА. Еще один кандидат подал в ЦИК документы для участия в выборах президента России. Комсомольская Правда (in Russian). Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ Нажбудинова, Амалия (28 December 2023). ""Коммунисты России" выдвинули Малинковича в кандидаты на выборах президента". Izvestia (in Russian). Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ "Об участии в президентских выборах 2024 года". Yabloko (in Russian). Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Кто может стать миллионером" [Who can become a millionaire]. Kommersant (in Russian). 10 December 2023. Archived from the original on 20 December 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ ""Яблоко" передумало выдвигать кандидата на выборы президента". Ведомости (in Russian). Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Явлинский отказался от выдвижения в президенты". RBC (in Russian). 23 December 2023. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Организаторам президентских праймериз лево-патриотических сил грозят уголовным делом". Left Front (in Russian). 13 December 2023. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ a b Marc Bennetts (12 June 2023). "Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin appeals to Russians with 'election poster'". The Times. Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ a b "«Я к этому отношения не имею». Пригожин прокомментировал Юга.ру листовки со своим фото, появившиеся в Краснодаре". Yuga (in Russian). 16 June 2023. Archived from the original on 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ a b Holger Roonemaa; Marta Vunsh; Anastasiia Morozova; Carina Huppertz; Mattias Carlsson; Mart Nigola; Hele-Mai Kulleste (26 February 2024), Kremlin Leaks: Secret Files Reveal How Putin Pre-Rigged his Reelection, VSquare, Wikidata Q124672623, archived from the original on 27 February 2024

- ^ a b "'People don't want to vote' How the Kremlin plans to compensate for Russians' record-low interest in the country's upcoming election". Meduza. 4 March 2024. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ Roth, Andrew (8 March 2024). "From patriotic films to youth festivals: the £1bn push to get vote out for Putin". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "A political education Putin's order to appoint political commissars responsible for 'strengthening patriotism' in Russian government bodies". Meduza. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Russia election: Stage-managed vote will give Putin another term". BBC News. 14 March 2024. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "Russia's presidential election: Three Putin challengers but little suspense". France 24. 15 March 2024. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Russia elections: Everything you need to know about sham presidential polls that will hand Putin fifth term". The Independent. 17 March 2024. Archived from the original on 17 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Russia Kicks Off Early Voting in Occupied Ukrainian Regions". The Moscow Times. 26 February 2024. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ "Institute for the Study of War". Institute for the Study of War. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Occupied Ukraine encouraged to vote in Russian election by armed men". BBC News. 12 March 2024. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "Inwoners van bezet Oekraïne werken onder dwang mee aan herverkiezing Poetin". NOS. 16 March 2024. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ "At gunpoint, Ukrainians in occupied regions vote in Russia's election". Al Jazeera. 17 March 2024. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Финита ля комедия – в Мелитополе закончились фейковые выборы. Что дальше? (фото, видео)". 17 March 2024. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "'Record falsification': Kremlin critics decry vote won by Russia's Putin". Al Jazeera. 20 March 2024. Archived from the original on 20 March 2024. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ a b "'Make the Young Fall in Love With Putin': Young Russians Pressured to Vote as Kremlin Demands Record Turnout". France 24. 14 March 2024. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Kremlin insiders weigh in on the record-breaking voting results reported for Vladimir Putin". Meduza. 18 March 2024.

- ^ "Russian election: Alexei Navalny's final plan to cause Vladimir Putin 'maximum damage'". Politico. 14 March 2024. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Bread Rolls and Dyson Hair Stylers: Russia Lures Voters With Election Day Freebies". The Moscow Times. 14 March 2024. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ Kozlov, Pyotr (14 March 2024). "'Make the Young Fall in Love With Putin': Young Russians Pressured to Vote as Kremlin Demands Record Turnout". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Russians are voting in an election that holds little suspense after Putin crushed dissent". Associated Press. 15 March 2024. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Putin Votes Online in Russian Presidential Election – TV". The Moscow Times. 15 March 2024. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ "Russia's Online Voting System Briefly Crashes on First Day of Election". The Moscow Times. 15 March 2024. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "At least 22 million fake votes cast for Putin in presidential election". Novaya Gazeta. 19 March 2024. ISSN 1606-4828. Wikidata Q125026372. Archived from the original on 20 March 2024.

- ^ "Исследование «Новой-Европа»: около половины голосов за Владимира Путина на президентских выборах были вброшены". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). 18 March 2024. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Russians cast ballots in an election preordained to extend President Vladimir Putin's rule". Associated Press. 17 March 2024. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Putin hails electoral victory that was preordained, after harshly suppressing opposition voices". Associated Press. 18 March 2024. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "VIDEO: Allegations emerge of disappearing ink being used on Russian election ballot paper that vanishes under lighter flame". TalkTV. 15 March 2024. Archived from the original on 21 March 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "Disappearing Ink: Another Item In Russia's Election Bag Of Tricks?". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 20 September 2021. Archived from the original on 27 December 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "Russian Presidential Vote an 'Imitation,' Election Watchdog Golos Says". The Moscow Times. 18 March 2024. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ Elsa Court (6 March 2024). "Exiled official: Russian election organizer killed in explosion in occupied Berdiansk". The Kyiv Independent. Archived from the original on 6 March 2024. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Russia election: Arrests for vandalism as ballot boxes targeted in Putin vote". BBC News. 15 March 2024. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ Martin Fornusek (16 March 2024). "National Resistance Center: Resistance disrupts 'voting' in occupied Skadovsk, injures 5 Russian troops". The Kyiv Independent. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ Lukiv, Jaroslav (12 March 2024). "Ukraine-based Russian armed groups claim raids into Russia". BBC News. Archived from the original on 12 March 2024. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ Elsa Court (13 March 2024). "Anti-Kremlin militia says fighting ongoing in 5 Russian settlements". The Kyiv Independent. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Kateryna Denisova (13 March 2024). "Putin: Cross-border incursion by Russian anti-Kremlin militia 'attempt to interfere in elections'". The Kyiv Independent. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "In Russian Border City, Election Must Go On Under Ukrainian Fire". The Moscow Times. 18 March 2024. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "Russia's FSB Thwarted Attack on Putin Campaign Office – Mediazona". The Moscow Times. 18 March 2024. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Russians Set Fire to At Least 4 Polling Stations on First Day of Election". The Moscow Times. 15 March 2024. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ "Multiple Russians arrested for pouring ink into ballot boxes, St. Petersburg woman throws Molotov cocktail at polling station". Meduza. 15 March 2024. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Russians are voting in an election that holds little suspense after Putin crushed dissent". Associated Press. 15 March 2024. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "St. Petersburg Woman Arrested for Writing 'No to War' on Voting Ballot". The Moscow Times. 20 March 2024. Archived from the original on 20 March 2024. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Russians crowd polling stations in apparent protest as Putin is set to extend his rule". Associated Press. 17 March 2024. Archived from the original on 17 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Moldova Police Detain Man After Firebombs at Russian Embassy". The Moscow Times. 17 March 2024. Archived from the original on 17 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.