Abraham ibn Ezra

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 18 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 18 min

Abraham ibn Ezra ראב"ע | |

|---|---|

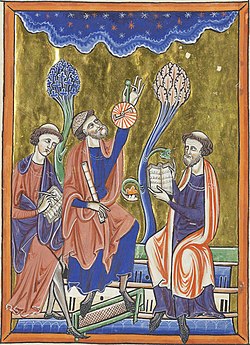

An illustration of Ibn Ezra (center) making use of an astrolabe. | |

| Born | c. 1089 - 1092 |

| Died | c. 1164 - 1167 |

| Known for | writing commentaries, grammarian |

| Children | Isaac ben Ezra |

Abraham ben Meir Ibn Ezra (Hebrew: ר׳ אַבְרָהָם בֶּן מֵאִיר אִבְּן עֶזְרָא, romanized: ʾAḇrāhām ben Mēʾir ʾiḇən ʾEzrāʾ, often abbreviated as ראב״ע; Arabic: إبراهيم المجيد ابن عزرا Ibrāhim al-Mājid ibn Ezra; also known as Abenezra or simply ibn Ezra, 1089 / 1092 – 27 January 1164 / 23 January 1167)[1][2] was one of the most distinguished Jewish biblical commentators and philosophers of the Middle Ages. He was born in Tudela, Taifa of Zaragoza (now Navarre).

Biography

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Jewish philosophy |

|---|

|

Abraham Ibn Ezra was born in Tudela, one of the oldest and most important Jewish communities in Navarre. At the time, the town was under the rule of the emirs of the Muslim Taifa of Zaragoza. However, when he later moved to Córdoba, he claimed it was his birthplace.[2] Ultimately, most scholars agree that his place of birth was Tudela.[citation needed]

From outside sources, little is known of ibn Ezra's family; however, he wrote of a marriage to a wife who produced five children. While it is believed four died early, the last-born, Isaac, became an influential poet and a later convert to Islam in 1140. His son's conversion was deeply troubling for ibn Ezra, leading him to pen many poems reacting to the event for years afterward.[3]

Ibn Ezra was a close friend of Judah Halevi, who was approximately 14 years older. When ibn Ezra moved to Córdoba as a young man, Halevi followed him. This trend continued when the two began their lives as wanderers in 1137. Halevi died in 1141, but Ibn Ezra continued travelling for three decades, reaching as far as Baghdad. During his travels, he composed secular poetry of the lands he traveled through and rationalist Torah commentaries (for which he would be best remembered).[2]

He appears to have been unrelated to the contemporary scholar Moses ibn Ezra.[4]

Works

[edit]

In Spain, Ibn Ezra had already gained the reputation of a distinguished poet and thinker.[5] However, apart from his poems, the vast majority of his work was composed after 1140. Written in Hebrew, as opposed to earlier thinkers' use of Judeo-Arabic, these works covering Hebrew grammar, Biblical exegesis, and scientific theory were tinged with the work of Arab scholars he had studied in Spain.

Beginning many of his writings in Italy, Ibn Ezra also worked extensively to translate the works of grammarian and biblical exegetist Judah ben David Hayyuj from their original Judeo-Arabic to Hebrew.[6] Published as early as 1140, these translations became some of the first expositions of Hebrew grammar to be written in Hebrew.[2]

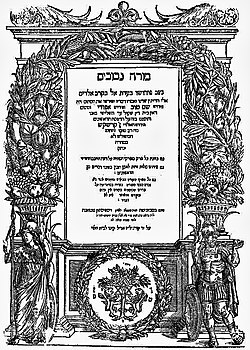

While publishing translations, Ibn Ezra also began to publish biblical commentaries. Using many of the techniques outlined by Hayyuj, Ibn Ezra would publish his first biblical commentary on Ecclesiastes in 1140.[6] He would continue to publish such commentaries over mainly works from Ketuvim and Nevi'im throughout his journey. He managed to publish a short commentary over the entire Pentateuch while living in Lucca in 1145. This brief commentary would be amended into more extended portions beginning in 1155 with the publication of his expanded commentary on Genesis.[6]

Besides his Torah commentaries, ibn Ezra also published many works in Hebrew on Islamic science. In doing so, he continued spreading the knowledge he had gained in Spain to the Jews throughout the areas he visited and lived. This can be seen particularly in the works he published while living in France. Many of the works he published relate to astrology and the use of the astrolabe.

Influence on biblical criticism and philosophy of religion

[edit]In his commentary, Ibn Ezra adhered to the literal sense of the texts, avoiding Rabbinic allegory and Kabbalistic interpretation.[7] He exercised an independent criticism that, according to some writers, exhibits a marked tendency toward rationalism.[8] In addition, he sharply criticized those who blended the simplistic and logical explanation with Midrash, maintaining that such interpretations were never intended to supplant the plain understanding.[9]

Indeed, Ibn Ezra is claimed by proponents of higher biblical criticism of the Torah as one of its earliest pioneers. Baruch Spinoza, in concluding that Moses did not author the Torah and that the Torah and other protocanonical books were written or redacted by somebody else, cites Ibn Ezra's commentary on Deuteronomy.[10] In his commentary, ibn Ezra examines Deuteronomy 1:1 and expresses concern over the unusual phrasing that describes Moses as being "beyond the Jordan." This wording suggests that the writer was situated in the land of Canaan, which is located west of the Jordan River, even though Moses and the Children of Israel had not yet crossed the Jordan at that point in the Biblical narrative.[11] Relating this inconsistency to others in the Torah, Ibn Ezra stated,

"If you can grasp the mystery behind the following problematic passages: 1) The final twelve verses of this book [i.e., Deuteronomy 34:1–12, describing the death of Moses], 2) 'Moshe wrote [this song on the same day, and taught it to the children of Israel]' [Deuteronomy 31:22]; 3) 'At that time, the Canaanites dwelt in the land' [Genesis 12:6]; 4) '... In the mountain of God, He will appear' [Genesis 22:14]; 5) 'behold, his [Og king of Bashan] bed is a bed of iron [is it not in Rabbah of the children of Ammon?]' you will understand the truth."[11]

Spinoza concluded that Ibn Ezra's reference to "the truth", and other such references scattered throughout Ibn Ezra's commentary in reference to seemingly anachronistic verses,[12] as "a clear indication that it was not Moses who wrote the Pentateuch but someone else who lived long after him, and that it was a different book that Moses wrote".[10] Spinoza and later scholars were thus able to expand on several of Ibn Ezra's references as a means of providing more substantial evidence for non-Mosaic authorship.[13]

On the other hand, Orthodox writers have stated that Ibn Ezra's commentary can be interpreted as consistent with Jewish tradition, stating that the Torah was divinely dictated to Moses.[14]

Ibn Ezra is also among the first scholars to have published a text about dividing the Book of Isaiah into at least two distinct parts. In his commentary to Isaiah, he remarked that chapters 1-39 dealt with a different historical period (second half of the 8th century BCE) than chapters 40-66 (later than the last third of the 6th century BCE). This division of the book into First Isaiah and Deutero-Isaiah has been accepted nowadays by all but the most conservative Jews and Christians.[15]

Ibn Ezra's commentaries, especially some of the longer excursuses, contain numerous contributions to the philosophy of religion. One work in particular that belongs to this province, Yesod Mora ("Foundation of Awe"), on the division and the reasons for the Biblical commandments, he wrote in 1158 for a London-based friend, Joseph ben Jacob. In his philosophical thought, Neoplatonic ideas prevail, and astrology also had a place in his view of the world. He also wrote various works on mathematical and astronomical subjects.[5][16]

He believed that Greek science had been "pillaged" from Hebrew science which predated it.[17]

Bibliography

[edit]Biblical commentaries

[edit]- Sefer ha-Yashar ("Book of the Straight"). The complete commentary on the Torah was finished shortly before his death.

Hebrew grammar

[edit]- Sefer Moznayim "Book of Scales" (1140), chiefly an explanation of the terms used in Hebrew grammar; as early as 1148, it was incorporated by Judah Hadassi in his Eshkol ha-Kofer, with no mention of Ibn Ezra.

- Sefer ha-Yesod, or Yesod Diqduq "Book of Language Fundamentals" (1143)

- Sefer Haganah 'al R. Sa'adyah Gaon, (1143) a defense of Saadyah Gaon against Dunash ben Labrat's criticisms.

- Tzakhoot (1145), on linguistic correctness, his best grammatical work, which also contains a brief outline of modern Hebrew meter.

- Sefer Safah Berurah "Book of Purified Language" (1146).

Smaller works – partly grammatical, partly exegetical

[edit]- Sefat Yeter, in defense of Saadia Gaon against Dunash ben Labrat, whose criticism of Saadia ibn Ezra had brought with him from Egypt.

- Sefer ha-Shem ("Book of the Name"), a work on the names of God.

- Yesod Mispar, a small monograph on numerals.

- Iggeret Shabbat (1158), a responsum on Shabbat

Religious philosophy

[edit]- Yesod Mora Vesod Hatorah (1158), on the division of and reasons for the Biblical commandments.

Mathematics

[edit]- Sefer ha-Ekhad, on the peculiarities of the numbers 1–9.

- Sefer ha-Mispar or Yesod Mispar, arithmetic.

- Luchot, astronomical tables.

- Sefer ha-'Ibbur, on the calendar.

- Keli ha-Nechoshet, on the astrolabe.

- Shalosh She'elot, in answer to three chronological questions of David ben Joseph Narboni.

Astrology

[edit]Ibn Ezra composed his first book on astrology in Italy, before his move to France:

- Mishpetai ha-Mazzelot ("Judgments of the Zodiacal Signs"), on the general principles of astrology

In seven books written in Béziers in 1147–1148 Ibn Ezra then composed a systematic presentation of astrology, starting with an introduction and a book on general principles, and then five books on particular branches of the subject. The presentation appears to have been planned as an integrated whole, with cross-references, including references to subsequent books in the future tense. Each of the books is known in two versions, so it seems that Ibn Ezra also created a revised edition of the series at some point.[18]

- Reshit Hokhma ("The Beginning of Wisdom"), an introduction to astrology, perhaps a revision of his earlier book

- Sefer ha-Te'amim ("Book of Reasons"), an overview of Arabic astrology, explaining the material in the previous book.

- Sefer ha-Moladot ("Book of Nativities"), on astrology based on the time and place of birth.

- Sefer ha-Me'orot ("Book of Luminaries" or "Book of Lights"), on medical astrology.

- Sefer ha-She'elot ("Book of Interrogations"), on questions about particular events.

- Sefer ha-Mivharim ("Book of Elections", also known as "Critical Days"), on optimum days for particular activities.

- Sefer ha-Olam ("Book of the World"), on the fates of countries and wars, and other larger-scale issues.

- Translation of two works by the astrologer Mashallah ibn Athari: "She'elot" and "Qadrut".

Poetry

[edit]There are a great many other poems by Ibn Ezra, some of them religious and some secular – about friendship, wine, didactic or satirical. Like his friend Yehuda Halevi, he used the Arabic poetic form of Muwashshah.

Legacy

[edit]The crater Abenezra on the Moon was named in honor of Ibn Ezra.

Robert Browning's poem "Rabbi ben Ezra", beginning "Grow old along with me/The best is yet to be", is derived from a meditation on Ibn Ezra's life and work that appeared in Browning's 1864 poetry collection Dramatis Personæ.[19]

Burial

[edit]According to Jewish tradition, Abraham ibn Ezra was buried in Cabul in the Lower Galilee alongside Judah Halevi.[20]

See also

[edit]- Rabbinic literature

- List of rabbis

- Jewish views of astrology

- Jewish commentaries on the Bible

- Kabbalistic astrology

- Astrology in Judaism

- Hebrew astronomy

- Islamic astrology

- Abenezra (crater)

References

[edit]- ^ Encyclopaedia Judaica, pages 1163–1164

- ^ a b c d Jewish Encyclopedia (online); Chambers Biographical Dictionary gives the dates 1092/93 – 1167

- ^ "IBN EZRA, ISAAC (ABU SA'D) - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ Mordechai Z. Cohen, The Rule of Peshat: Jewish Constructions of the Plain Sense of Scripture and Their Christian and Muslim Contexts, 900-1270, p. 209

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bacher, William (1911). "Abenezra". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 42.

- ^ a b c Sela, Shlomo; Freudenthal, Gad (2006). "Abraham Ibn Ezra's Scholarly Writings: A Chronological Listing". Aleph. 6 (6): 13–55. doi:10.1353/ale.2006.0006. ISSN 1565-1525. JSTOR 40385893. S2CID 170244695.

- ^ Avigail Rock, Lecture #13: R. Avraham ibn Ezra, Part I

- ^ see the introduction to Yam Shel Shlomo by Rabbi Shlomo Luria

- ^ שפה ברורה. מוסד הרב קוק. pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b "A Theologico-Political Treatise: Part 2: Chapter VIII.—Of the Authorship of the Pentateuch and the Other Historical Books of the Old Testament". www.sacred-texts.com.

- ^ a b Jay F. Schachter, The Commentary of Abraham Ibn Ezra on the Pentateuch: Volume 5, Deuteronomy (KTAV Publishing House 2003)

- ^ For example, Spinoza understood Ibn Ezra's commentary on Genesis 12:6 ("And the Canaanite was then in the land"), wherein Ibn Ezra esoterically stated that "some mystery lies here, and let him who understands it keep silent," as proof that Ibn Ezra recognized that at least certain Biblical passages had been inserted long after the time of Moses.

- ^ See for example, "Who wrote the Bible" and the "Bible with Sources Revealed", both by Richard Elliott Friedman

- ^ ""The Canaanites Were Then in the Land": Ibn Ezra, Post-Mosaic Editorial Insertions, and the Canaanite Exile from the Land - Text & Texture". text.rcarabbis.org.

- ^ "Isaiah and Deutero-Isaiah" (PDF).

- ^ J. J. O'Connor; E. F. Robertson. "Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra".

- ^ Shavit, Yaacov (August 10, 2020), "Chapter Eight. Solomon, Aristoteles Judaicus, and the Invention of a Pseudo- Solomonic Library", An Imaginary Trio, De Gruyter, pp. 172–190, doi:10.1515/9783110677263-010, ISBN 978-3-11-067726-3, retrieved May 8, 2025

- ^ Shlomo Sela (2000), "Encyclopedic aspects of Ibn Ezra's scientific corpus", in Steven Harvey (ed), The Medieval Hebrew Encyclopedias of Science and Philosophy: Proceedings of the Bar-Ilan University Conference, Springer. ISBN 0-7923-6242-X. See pp. 158 et seq.

- ^ Robert Browning (1864/1969), Dramatis Personae, reprint, London: Collins

- ^ Levi-Naḥum, Yehuda (1986). "The graves of the fathers and of the righteous". Sefer ṣohar le-ḥasifat ginzei teiman (in Hebrew). Ḥolon, Israel: Mifʻal ḥaśifat ginze Teman. p. 252. OCLC 15417732.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "IBN EZRA, ABRAHAM BEN MEÏR (ABEN EZRA)". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "IBN EZRA, ABRAHAM BEN MEÏR (ABEN EZRA)". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Further reading

[edit]- Carmi, T. (ed.), The Penguin book of Hebrew verse, Penguin Classics, 2006, London ISBN 978-0-14-042467-6

- Charlap, Luba. 2001. Another view of Rabbi Abraham Ibn-Ezra's contribution to medieval Hebrew grammar. Hebrew Studies 42:67-80.

- Epstein, Meira, "Rabbi Avraham Ibn Ezra" – An article by Meira Epstein, detailing all of ibn Ezra's extant astrological works

- Glick, Thomas F.; Livesey, Steven John; and Wallis, Faith, Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0-415-96930-1. Cf. pp. 247–250.

- Goodman, Mordechai S. (Translator), The Sabbath Epistle of Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra,('iggeret hashabbat). Ktav Publishing House, Inc., New Jersey (2009). ISBN 978-1-60280-111-0

- Halbronn, Jacques, Le monde juif et l'astrologie, Ed Arché, Milan, 1985

- Halbronn, Jacques, Le livre des fondements astrologiques, précédé du Commencement de la Sapience des Signes, Pref. G. Vajda, Paris, ed Retz 1977

- Holden, James H., History of Horoscopic Astrology, American Federation of Astrologers, 2006. ISBN 0-86690-463-8. Cf. pp. 132–135.

- Jewish Virtual Library, Abraham Ibn Ezra

- Johansson, Nadja, Religion and Science in Abraham Ibn Ezra's Sefer Ha-Olam (Including an English Translation of the Hebrew Text)

- Langermann, Tzvi, "Abraham Ibn Ezra", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2006. Accessed June 21, 2011.

- Levin, Elizabetha, Various Times in Abraham Ibn Ezra's Works and their Reflection in Modern Thought // KronoScope, Brill Academic Publishers,18, Issue 2, 2018, pp. 154–170. DOI: 10.1163/15685241-12341414

- Levine, Etan. Ed., Abraham ibn Ezra's Commentary to the Pentateuch, Vatican Manuscript Vat. Ebr. 38. Jerusalem: Makor, 1974.

- Sánchez-Rubio García, Fernando (2016). El segundo comentario de Abraham Ibn Ezra al libro del Cantar de los Cantares. Edición crítica, traducción, notas y estudio introductorio. Tesis doctoral (UCM)

- Sela, Shlomo, "Abraham Ibn Ezra's Scientific Corpus Basic Constituents and General Characterization", in Arabic Sciences and Philosophy, (2001), 11:1:91–149 Cambridge University Press

- Sela, Shlomo, Abraham Ibn Ezra and the Rise of Medieval Hebrew Science, Brill, 2003. ISBN 90-04-12973-1

- Siegel, Eliezer, Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra's Commentary to the Torah

- skyscript.co.uk, 120 Aphorisms for Astrologers by Abraham ibn Ezra

- skyscript.co.uk, Skyscript: The Life and Work of Abraham Ibn Ezra

- Smithuis, Renate, "Abraham Ibn Ezra's Astrological Works in Hebrew and Latin: New Discoveries and Exhaustive Listing", in Aleph (Aleph: Historical Studies in Science and Judaism), 2006, No. 6, Pages 239-338

- Wacks, David. "The Poet, the Rabbi, and the Song: Abraham ibn Ezra and the Song of Songs". Wine, Women, and Song: Hebrew and Arabic Literature in Medieval Iberia. Eds. Michelle M. Hamilton, Sarah J. Portnoy and David A. Wacks. Newark, Del.: Juan de la Cuesta Hispanic Monographs, 2004. 47–58.

- Walfish, Barry, "The Two Commentaries of Abraham Ibn Ezra on the Book of Esther", The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Series, Vol. 79, No. 4 (April 1989), pp. 323–343, University of Pennsylvania Press

External links

[edit]- Encyclopaedia Judaica (2007) entry on "Ibn Ezra, Abraham Ben Meir" with extensive bibliography by Uriel Simon and Raphael Jospe

- Rudavsky, Tamar M. (2007). "Ibn ʿEzra: Abraham ibn ʿEzra". In Thomas Hockey; et al. (eds.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 553–5. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0.

- Levey, Martin (2008) [1970-80]. "Ibn Ezra, Abraham Ben Meir". Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Encyclopedia.com.

- Roth, Norman. Ibn Ezra: Highlights of His Life.

- Commentaries over the Torah at Sefaria

- Poems in Hebrew at Ben Yehuda Project

|

KSF

KSF