Acanthus (ornament)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 10 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 10 min

The acanthus (Ancient Greek: ἄκανθος) is one of the most common plant forms to make foliage ornament and decoration in the architectural tradition emanating from Greece and Rome.[1]

Architecture

[edit]

In architecture, an ornament may be carved into stone or wood to resemble leaves from the Mediterranean species of the Acanthus genus of plants, which have deeply cut leaves with some similarity to those of the thistle and poppy. Both Acanthus mollis and the still more deeply cut Acanthus spinosus have been claimed as the main model, and particular examples of the motif may be closer in form to one or the other species; the leaves of both are, in any case, rather variable in form. The motif is found in decoration in nearly every medium.

The relationship between acanthus ornament and the acanthus plant has been the subject of a long-standing controversy. Alois Riegl argued in his Stilfragen that acanthus ornament originated as a sculptural version of the palmette, and only later began to resemble Acanthus spinosus.[2]

Greek and Roman

[edit]In ancient Roman and ancient Greek architecture acanthus ornament appears extensively in the capitals of the Corinthian and Composite orders, and applied to friezes, dentils and other decorated areas. The oldest known example of a Corinthian column is in the Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae in Arcadia, c. 450–420 BC, but the order was used sparingly in Greece before the Roman period. The Romans elaborated the order with the ends of the leaves curled, and it was their favourite order for grand buildings, with their own invention of the Composite, which was first seen in the epoch of Augustus.[3] Acanthus decoration continued in popularity in Byzantine, Romanesque, and Gothic architecture. It saw a major revival in the Renaissance, and still is used today.

The Roman writer Vitruvius (c. 75 – c. 15 BC) related that the Corinthian order had been invented by Callimachus, a Greek architect and sculptor who was inspired by the sight of a votive basket that had been left on the grave of a young girl. A few of her toys were in it, and a square tile had been placed over the basket, to protect them from the weather. An acanthus plant had grown through the woven basket, mixing its spiny, deeply cut leaves with the weave of the basket.

Byzantine

[edit]Some of the most detailed and elaborate acanthus decoration occurs in important buildings of the Byzantine architectural tradition, where the leaves are undercut, drilled, and spread over a wide surface. Use of the motif continued in Medieval art, particularly in sculpture and wood carving and in friezes, although usually it is stylized and generalized, so that one doubts that the artists connected it with any plant in particular. After centuries without decorated capitals, they were revived enthusiastically in Romanesque architecture, often using foliage designs, including acanthus. Curling acanthus-type leaves occur frequently in the borders and ornamented initial letters of illuminated manuscripts, and are commonly found in combination with palmettes in woven silk textiles. In the Renaissance classical models were followed closely, and the acanthus becomes recognisable again in large-scale architectural examples. The term is often also found describing more stylized and abstracted foliage motifs, where the similarity to the species is weak.

Gallery

[edit]-

Acanthuses, one natural and the rest manmade, on a Corinthian capital

-

Reconstructed Corinthian capital, with original colours

-

Ancient Greek Corinthian capital from the tholos at Epidaurus, Archaeological Museum of Epidaurus, Greece, said to have been designed by Polyclitus the Younger, c.350 BC[4]

-

Roman acanthuses that replace the legs of a figure of a man that is attacked by a panther, Sala della Sfinge, Domus Aurea, Rome, unknown painter, 65-68 AD

-

Byzantine quasi-Corinthian capital of the Column of Leo, formerly in the Forum of Leo, Constantinople, now in a courtyard of the Topkapı Palace, Fatih, Istanbul, Turkey, unknown architect or sculptor, 457-474

-

Byzantine acanthuses on the cornice at the top of the Pilastri Acritani (Pillars of Acre), originally in the Church of St. Polyeuctus, later taken and now displayed in the Piazzetta di San Marco, Venice, unknown architect or sculptor, 524-527[6]

-

Byzantine quasi-Corinthian capital in the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy, unknown architect or sculptor, 6th century

-

Islamic capital with acanthuses, 10th century, marble, Cincinnati Art Museum, US

-

Romanesque quasi-Corinthian capital of the Church of St. Philibert, Tournus, France, unknown architect or sculptor, c.1008 to mid-11th century[7]

-

Romanesque quasi-Corinthian capital of the Chapelle Notre-Dame-de-Nazareth d'Entrechaux, Entrechaux, France, unknown architect or sculptor, 12th century

-

Gothic acanthus on a corbel of the Vienne Cathedral, Vienne, France, unknown architect or sculptor, c.1130-1529

-

Gothic acanthuses on a page of the Codex Salemitanus IX c, 15th century, tempera colors, gold paint, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, Heidelberg University Library, Heidelberg, Germany

-

Renaissance acanthuses on the fabric worn by king Edward IV, portrait painted by Lucas Horenbout, c.1470-1475

-

Gothic acanthuses on the Hôtel de Cluny, Paris, unknown architect or sculptor, 1485-1510[8]

-

Baroque acanthuses of a monogram of Louis XIV on the entrance door of the Dôme des Invalides, Paris, by Jules Hardouin-Mansart, 1677–1706[9]

-

Brâncovenesc acanthuses of a railing of the Potlogi Palace, Potlogi, Romania, unknown architect or sculptor, 1698

-

Brâncovenesc acanthuses of a railing of the Horezu Monastery, Horezu, Romania, unknown architect or sculptor, 17th-18th centuries[10]

-

Baroque acanthuses on a commode, by André-Charles Boulle, c.1710–1720, walnut veneered with ebony, marquetry of engraved brass and tortoiseshell, and gilt-bronze mounts, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Baroque mascaron with acanthuses in the Salon d'Hercule, 1724–1736, designed by Robert de Cotte, Jacques Gabriel

-

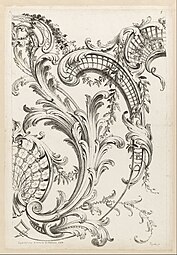

Rococo acanthus, by Alexis Peyrotte, 1740, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York

-

Rococo acanthuses on a wall of the oval salon of the Princesse in Hôtel de Soubise, Paris, by Germain Boffrand, 1740[11]

-

Neoclassical acanthuses of a staircase railing in the Petit Trianon, Versailles, France, by Ange-Jacques Gabriel, 1764[12]

-

Neoclassical acanthuses on a vase, by the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory, 1814, hard-paste porcelain with platinum background and gilt bronze mounts, Louvre[13]

-

Neoclassical acanthuses on the ceiling of the Salon des Sept cheminées, Louvre Palace, Paris, by Francisque Duret, 1851[14]

-

Beaux Arts acanthuses on the base of a column in the Grand Foyer of the Palais Garnier, Paris, designed by Charles Garnier, 1860–1875[15]

-

Greek Revival Corinthian pilasters on the Austrian Parliament Building, Vienna, by Theophil von Hansen, 1873–1883[16]

-

Neoclassical terracotta and enamel acanthuses of the door of the fine art hall of the Exposition Universelle of 1878, Paris, by Paul Sedille, 1878

-

Romanian Revival acanthuses on a stained-glass window of the Kiseleff Roadside Buffet (Șoseaua Kiseleff no. 4), Bucharest, Romania, by Ion Mincu, 1889-1892[17]

-

Romanian Revival glazed ceramic acanthus in the courtyard of the Central Girls' School (Strada Icoanei no. 3-5), Bucharest, by Ion Mincu, 1890[18]

-

Romanian Revival acanthuses on the Gheorghieff Brothers Tomb, Bellu Cemetery, Bucharest, by Ion Mincu, c.1900

-

Art Nouveau and Gothic Revival acanthus designed as a bronze element of a stained glass window of Bijouterie Fouquet in Paris, by Alphonse Mucha, c.1900, charcoal drawing, Musée Carnavalet, Paris

-

Art Nouveau corbels with Byzantine Revival acanthuses on the portico monumental Jules-Félix Coutan in the Félix-Desruelles Square, Paris, by Jules Coutan and the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory, 1900

-

Romanian Revival acanthuses of fish in a relief of Strada Louis Pasteur no. 24, Bucharest, unknown architect, c.1930

-

Romanian Revival capital with acanthuses of Strada Carol Davila no. 12, Bucharest, unknown architect, c.1930

-

Postmodern neon Corinthian capital in South Bay Galleria, Redondo Beach, California, US, by RTKL Associates and Theo Kondos Associates, 1985

-

Postmodern acanthus leave on the leg of a table with different legs, unknown designer, c.2010, painted wood, Cărturești Verona (Strada Arthur Verona no. 15), Bucharest

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Lewis & Darley 1986, p. 20.

- ^ Riegl 1992, pp. 187–206.

- ^ Strong, D. E. (1960). "Some early examples of the composite capital". Journal of Roman Studies. 50: 119–128. doi:10.2307/298294. JSTOR 298294. S2CID 162473543.

- ^ Honour & Fleming 2009, p. 147.

- ^ Robertson 2022, p. 323.

- ^ Eastmond, Anthony (2013). The Glory of Byzantium and early Christendom. Phaidon. p. 81. ISBN 978 0 7148 4810 5.

- ^ Watkin 2022, p. 123.

- ^ "Ancien hôtel de Cluny et Palais des Thermes, actuellement Musée National du Moyen Âge". pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ Bailey 2012, pp. 238.

- ^ Florea 2016, p. 243.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 241.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 273.

- ^ "PAIRE DE VASES « FUSEAU »". amisdulouvre.fr. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ Bresc-Bautier 2008, p. 122.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 296.

- ^ Watkin 2022, p. 490.

- ^ Celac, Carabela & Marcu-Lapadat 2017, p. 153.

- ^ Celac, Carabela & Marcu-Lapadat 2017, p. 123.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 294.

References

[edit]- Bailey, Gauvin Alexander (2012). Baroque & Rococo. Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-5742-8.

- Bresc-Bautier, Geneviève (2008). The Louvre, a Tale of a Palace. Musée du Louvre Éditions. ISBN 978-2-7572-0177-0.

- Celac, Mariana; Carabela, Octavian; Marcu-Lapadat, Marius (2017). Bucharest Architecture - an annotated guide. Order of Architects of Romania. ISBN 978-973-0-23884-6.

- Florea, Vasile (2016). Arta Românească de la Origini până în Prezent (in Romanian). Litera. ISBN 978-606-33-1053-9.

- Honour, Hugh; Fleming, John (2009). A World History of Art - Revised Seventh Edition. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85669-584-8.

- Jones, Denna, ed. (2014). Architecture The Whole Story. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-29148-1.

- Lewis, Philippa; Darley, Gillian (1986). Dictionary of Ornament. New York: Pantheon. ISBN 9780394509310.

- Riegl, A (1992). Problems of style: foundations for a history of ornament. Translated by Kain, E. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-65658-8.

- Robertson, Hutton (2022). The History of Art - From Prehistory to Presentday - A Global View. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-02236-8.

- Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Hopkins, Owen (2014). Architectural Styles: A Visual Guide. Laurence King. ISBN 978-178067-163-5.

External links

[edit] Media related to Acanthus ornaments at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Acanthus ornaments at Wikimedia Commons

KSF

KSF

![Ancient Greek Corinthian capital from the tholos at Epidaurus, Archaeological Museum of Epidaurus, Greece, said to have been designed by Polyclitus the Younger, c.350 BC[4]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6d/Corinthian_capital%2C_AM_of_Epidauros%2C_202545.jpg/384px-Corinthian_capital%2C_AM_of_Epidauros%2C_202545.jpg)

![Roman acanthuses in an arabesque on the Ara Pacis, Rome, unknown architect and sculptors, 13-9 BC[5]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/97/Panel_of_Tellus%2C_Ara_Pacis%2C_Rome_%28II%29.jpg/170px-Panel_of_Tellus%2C_Ara_Pacis%2C_Rome_%28II%29.jpg)

![Byzantine acanthuses on the cornice at the top of the Pilastri Acritani (Pillars of Acre), originally in the Church of St. Polyeuctus, later taken and now displayed in the Piazzetta di San Marco, Venice, unknown architect or sculptor, 524-527[6]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/35/Pilastri_Acritani.jpg/340px-Pilastri_Acritani.jpg)

![Romanesque quasi-Corinthian capital of the Church of St. Philibert, Tournus, France, unknown architect or sculptor, c.1008 to mid-11th century[7]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ef/Tournus_%2871%29_Abbatiale_Saint-Philibert_-_Int%C3%A9rieur_-_Chapiteau_-_13.jpg/170px-Tournus_%2871%29_Abbatiale_Saint-Philibert_-_Int%C3%A9rieur_-_Chapiteau_-_13.jpg)

![Gothic acanthuses on the Hôtel de Cluny, Paris, unknown architect or sculptor, 1485-1510[8]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/38/Visite_H%C3%B4tel_de_Cluny_07_juillet_2015_4326.jpg/383px-Visite_H%C3%B4tel_de_Cluny_07_juillet_2015_4326.jpg)

![Baroque acanthuses of a monogram of Louis XIV on the entrance door of the Dôme des Invalides, Paris, by Jules Hardouin-Mansart, 1677–1706[9]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/72/Paris_-_le_D%C3%B4me_des_Invalides_-_d%C3%A9tail_de_la_porte_-_104.jpg/170px-Paris_-_le_D%C3%B4me_des_Invalides_-_d%C3%A9tail_de_la_porte_-_104.jpg)

![Brâncovenesc acanthuses of a railing of the Horezu Monastery, Horezu, Romania, unknown architect or sculptor, 17th-18th centuries[10]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d0/Horezu_bicefal_eagle.JPG/340px-Horezu_bicefal_eagle.JPG)

![Rococo acanthuses on a wall of the oval salon of the Princesse in Hôtel de Soubise, Paris, by Germain Boffrand, 1740[11]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/81/Salon_ovale_de_la_princesse_in_the_H%C3%B4tel_de_Soubise_%2810%29.jpg/331px-Salon_ovale_de_la_princesse_in_the_H%C3%B4tel_de_Soubise_%2810%29.jpg)

![Neoclassical acanthuses of a staircase railing in the Petit Trianon, Versailles, France, by Ange-Jacques Gabriel, 1764[12]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/41/D%C3%A9part_de_la_rampe_de_l%27escalier_int%C3%A9rieur_du_Petit_Trianon.jpg/169px-D%C3%A9part_de_la_rampe_de_l%27escalier_int%C3%A9rieur_du_Petit_Trianon.jpg)

![Neoclassical acanthuses on a vase, by the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory, 1814, hard-paste porcelain with platinum background and gilt bronze mounts, Louvre[13]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f4/Pair_of_Spindle_Vases_-_OA_11090_-_Louvre_%2808%29.jpg/306px-Pair_of_Spindle_Vases_-_OA_11090_-_Louvre_%2808%29.jpg)

![Neoclassical acanthuses on the ceiling of the Salon des Sept cheminées, Louvre Palace, Paris, by Francisque Duret, 1851[14]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/35/Ceiling_of_the_Salle_des_Sept-Chemin%C3%A9es_in_the_Louvre_Palace_%2828223543502%29.jpg/383px-Ceiling_of_the_Salle_des_Sept-Chemin%C3%A9es_in_the_Louvre_Palace_%2828223543502%29.jpg)

![Beaux Arts acanthuses on the base of a column in the Grand Foyer of the Palais Garnier, Paris, designed by Charles Garnier, 1860–1875[15]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4a/Base_of_a_column_in_the_Grand_foyer_of_the_Op%C3%A9ra_Garnier.jpg/159px-Base_of_a_column_in_the_Grand_foyer_of_the_Op%C3%A9ra_Garnier.jpg)

![Greek Revival Corinthian pilasters on the Austrian Parliament Building, Vienna, by Theophil von Hansen, 1873–1883[16]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0b/Austrian_Parliament_Building_-_colored_sections_04.jpg/355px-Austrian_Parliament_Building_-_colored_sections_04.jpg)

![Romanian Revival acanthuses on a stained-glass window of the Kiseleff Roadside Buffet [ro] (Șoseaua Kiseleff no. 4), Bucharest, Romania, by Ion Mincu, 1889-1892[17]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/92/4_%C8%98oseaua_Pavel_D._Kiseleff%2C_Bucharest_%2801%29.jpg/224px-4_%C8%98oseaua_Pavel_D._Kiseleff%2C_Bucharest_%2801%29.jpg)

![Romanian Revival glazed ceramic acanthus in the courtyard of the Central Girls' School (Strada Icoanei no. 3-5), Bucharest, by Ion Mincu, 1890[18]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7b/3-5_Strada_Icoanei%2C_Bucharest_%2844%29.jpg/262px-3-5_Strada_Icoanei%2C_Bucharest_%2844%29.jpg)

![Beaux Arts acanthuses on the Petit Palais, Paris, by Charles Giraud, 1900[19]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/42/PetitPalaisParisIngresso.jpg/191px-PetitPalaisParisIngresso.jpg)