Akiva Eiger

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 64 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 64 min

Rabbi Akiva Eiger עקיבא אייגער | |

|---|---|

Engraving of Rabbi Akiva Eiger (1830’s) | |

| Personal | |

| Born | 8 November 1761 (11 Cheshvan 5522 Anno Mundi) |

| Died | 12 October 1837 (aged 75) (13 Tishrei 5598 Anno Mundi) |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Children | Solomon Eger Sarah Eger |

| Denomination | Orthodox Judaism |

| Occupation | Rabbi |

| Signature |  |

| Buried | Poznań |

| Residence | Markisch Friedland, Posen |

Rabbi Akiva Eiger (/eɪɡər/, also spelled Eger; Hebrew: עקיבא איגר, Yiddish: עקיבא אייגער), or Akiva Güns (8 November 1761 – 12 October 1837)[a] was a Talmudic scholar, halakhic decisor and leader of European Jewry during the early 19th century.

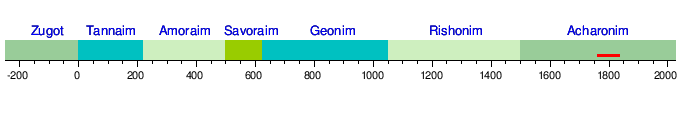

Eger is considered one of the greatest Talmudic scholars of modern times and among the most prominent. His name has become synonymous with Talmudic genius in Jewish scholarly culture, and his Torah is studied in the Batei Midrash of contemporary yeshivas. His methods of study and the logic he applied remain relevant today, unlike other Aharonim who tended towards Pilpul. In addition to his significant influence on the study of the Talmud and the works of the Rishonim, Rabbi Akiva Eger had a decisive impact in the field of halakha. His glosses printed on the margins of the Shulchan Aruch, as well as his responsa in his Shut works, are foundational elements in the world of daily halachic ruling and the realm of Dayanut.[1]

At the beginning of his career, he avoided taking on a rabbinical position involving halachic rulings but did not refrain from serving as a rosh yeshiva. Later, he served for 24 years as the rabbi of the town of Markisch-Friedland. His main public activity began when, after the efforts of his famous son-in-law, the Chatam Sofer, he was elected as the rabbi of the Polish district city of Posen, a position he held for 23 years, until his death.

Biography

[edit]His youth

[edit]Akiva Eger was born on 1 Cheshvan 5522 (October 29, 1761).[2] in Eisenstadt.[3] located in western Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary (now in Burgenland, Austria), one of the "Seven Communities."[4] His brit milah is recorded in the circumcision register of the mohel Rabbi Binyamin Wolf Tevin, a leader of the Pressburg community, and it was performed on 9 Cheshvan,[5] not on time.[6] He was the eldest son of Rabbi Moshe Ginz and Gittel Eger.

His mother, Gittel, whom her brother described as "righteous and learned like a man",[7] was the daughter of Rabbi Akiva Eger of Halberstadt, author of the book "Mishnat DeRabbi Akiva," rabbi of Zülz and Pressburg, considered one of the great rabbis of German Jewry and of the Holy Roman Empire. Rabbi Eger of Halberstadt at age 39, and his daughter Gittel chose to name her eldest son after him, Akiva. Rabbi Akiva Eger always signed his letters: "Akiva Ginz of AS" (Eisenstadt), like his father, but on official documents, he signed "Yaakov Moshe Eger," where the name "Yaakov" is an anagram of "Akiva,"[8] and "Moshe" represents his father's name. Later, during his lifetime, the family adopted the mother's surname "Eger" as it was considered genealogically more prestigious.[9] His father, Rabbi Moshe Ginz, was the son of Rabbi Shmuel Schlesinger and Sarah, the daughter of Rabbi Moshe Broda, and the granddaughter of Rabbi Avraham Broda, rabbi of Prague and Frankfurt.

As a child, he was recognized for his quick comprehension and phenomenal memory, and his parents directed him to study Talmud at a very young age. His name began to spread among scholars in the area when, at just six or seven years old, he solved a difficult Talmudic sugya that had stumped the greatest minds at the Breslau yeshiva for a long time without resolution. The question was sent to his father by his uncle, Rosh Yeshiva Binyamin Wolf Eger, who later became the rabbi of Zülz and Leipnik (Lipnik). The solution proposed by the young Eger earned him the reputation of a child prodigy and sparked curiosity. Many sought to meet him and witness his abilities firsthand.[10] At the age of seven, his father sent him to Mattersdorf to study under the local rabbi, Rabbi Natan Nata Frankfurter.[11] When he turned 12, he returned to Eisenstadt, where he primarily studied with his father and the city's new rabbi, Rabbi Asher Lemmel from Glogau (Głogów) in Silesia, Prussia (today in Poland).[12]

Over the years, after his uncle (his mother's brother) recognized his level of Torah knowledge, he persuaded his parents to send him for advanced studies at his yeshiva in Breslau. Due to his age, his parents preferred to keep him close to home, so he was briefly sent to the nearby Hungarian city of Mattersdorf, to the local rabbi's yeshiva, where he strengthened his knowledge and confidence.[13] At age 12 (5533, 1773), he traveled to Breslau and became the close student of his uncle, Rabbi Wolf Eger, who even designated him as his successor should he be absent. In this yeshiva, he met Rabbi Yeshaya Pick Berlin, who later became the rabbi of Breslau and was known for his glosses on the Babylonian Talmud printed as additions to the "Masoret HaShas" on the pages of Vilna Shas.

The Lissa period

[edit]

In the summer of 1781, when he was about 20 years old, he married Glickl,[14] the 18-year-old daughter (born 1763) of the wealthy Yitzchak (Itzik) Margolis of Lissa. The wedding took place in Lissa.[15] According to their prior agreement, Rabbi Akiva Eger settled in Lissa. His father-in-law provided him with a large, well-furnished house, including a rich library, and also supported him financially so that he could devote himself to Torah study. During his time in Lissa, he befriended Rabbi Yehuda Neuburg, the rabbi of Ravicz (Rawitsch), son-in-law of Rabbi Meir Posner, author of the "Beit Meir," who later corresponded with Eger. Rabbi David Tevel ben Natan Neta of Lissa also included him in his rabbinical court during his stay in the city.

In Lissa, Rabbi Akiva Eger and Glickl had their first three children:

- Avraham (late 1781–1853): Rabbi Avraham Eger, Rabbi Akiva Eger's eldest son, later married a woman from Ravicz (Rawitsch) near Posen (Poznań) and settled there. He eventually became the rabbi of Rogozin. He spent much time editing and preparing his father's works for print. He died on 1 Kislev 5614 (1853) and was buried in Posen.

- Shlomo (1787–1852): Rabbi Shlomo Eger, later the rabbi of Kalisz, who succeeded his father as the rabbi of Posen.

- Sheindel (1788–?): She later married Rabbi Moshe Heinrich Davidson of Bromberg.[16]

While still in Lissa, Rabbi Akiva Eger established a yeshiva in the house provided by his father-in-law, and students began gathering around him, some of whom later became rabbis themselves and maintained correspondence with their teacher. This arrangement continued until the winter of 1789–1790 (5550). In the middle of Shevat 5550, Rabbi Akiva Eger's father died, and he mourned deeply. That summer[17] a fire broke out, destroying most of the Jewish homes in Lissa, including the properties of his father-in-law Itzik Margolis, who was left destitute with his extended family. The yeshiva students dispersed, and Rabbi Akiva Eger was forced to move to the nearby city of Ravicz, where he was appointed as a dayan (rabbinical judge). His economic situation in Ravicz worsened daily, and the small Jewish community could not afford the salaries for its religious leaders.

The Markisch-Friedland period

[edit]

Initially, Rabbi Akiva Eger was reluctant to accept a rabbinical position, preferring to be a rosh yeshiva and teach students, relying on a living stipend provided by local Jewish benefactors. However, financial difficulties eventually forced him to take on a rabbinical position. In 1791, after the great fire in Lissa and the ensuing economic crisis, as well as the loss of his father-in-law's fortune, and following a trial period in the city of Ravicz, Rabbi Akiva Eger was appointed, through the intervention of his father-in-law and friends, to serve as the rabbi of Markisch-Friedland in West Prussia, a position he held for 24 years, beginning on 18 Adar I 5551.

Immediately upon his arrival in Markisch-Friedland, he established a yeshiva and began gathering many students, including those from his previous yeshiva in Lissa. As was customary at the time, the local Jewish community funded the rabbi's yeshiva and its students, in addition to his regular salary. The community board's protocol in Markisch-Friedland, detailing the new rabbi's salary terms, dated 8 Adar I 5551 (1791), has been preserved.[18] In this agreement, under the title,

"We have all agreed to accept the rabbi among us, to guide the people of Israel in the way they should go, and we have resolved that his meal will always come from this..."

his monthly salary is detailed in the local currency (Reichstaler), including special pay for his sermons on Shabbat Shuva and Shabbat HaGadol, Kimcha D'Pischa (Passover flour), Four Cups, Etrog and Lulav, free accommodation in the rabbi's residence, notary fees for certifying marriages and inheritance agreements. The agreement also specified the occasions on which the rabbi was entitled to be called to the Torah and to read the Haftarah. Additionally, it stipulated that the rabbi would serve as the Sandak (godfather) at the first brit milah (circumcision) conducted each month in the community. The initial salary was modest, and Rabbi Akiva Eger, who saw that it was insufficient to support his family, suspected that the community leaders assumed he had savings from the dowry he received from his wealthy father-in-law. However, as he did not have such funds, he approached the community board to request a raise, emphasizing that he only wished to receive the minimum necessary for his subsistence:

To the esteemed leaders, noblemen, officers, chiefs, and community leaders of the holy congregation of Markisch-Friedland!

I appeal to you and express my feelings to inform you that the salary granted to me, along with all income, does not even reach two-thirds of the necessary expenses, and I cannot sustain myself on this. Undoubtedly, your intention is not for me to live in hardship, nor for me to seek another path for sustenance. Do not think that I possess great wealth or have support from elsewhere, for it is not so. Therefore, my request from you is to give your attention to this and provide me with a fixed salary that would suffice minimally. If I had five Reichstaler per week as a fixed salary, I think it would cover my needs, albeit minimally.

These are the words of your friend, speaking from his heart The humble Akiva the son of our teacher Rabbi Moshe Ginz of blessed memory.

During the early period of his tenure in Markisch-Friedland, his fourth child, Sharl (Sarah), was born.[19] She was married in her first match to Rabbi Avraham Moshe Kalischer, the rabbi of Schneidermuhl, the son of Rabbi Yehuda Leib Kalischer of Lissa, author of the "Yad HaChazakah." His daughter Tzipora, born in Markisch-Friedland, died in her youth.[20]

During the Markisch-Friedland period, Rabbi Akiva Eger established his first students.[21] His innovations on the Talmud and his annotations on the Mishnah and Shulchan Aruch were mostly written there. Rabbi Akiva Eger began responding to halachic queries from across Europe and became known as one of the greatest halachic respondents of his generation. His responsa from this period are addressed to the rabbis of major communities in Italy, Germany, Moravia, Poland, and Russia.[22] Even the local authorities entrusted him with decisions concerning Jewish life.

In addition to issuing halachic rulings, studying, and spreading Torah, Rabbi Akiva Eger was involved in all public needs in his city, especially those of the disadvantaged. He served as a member of the Board of Directors in all charity organizations in the city and even founded specific charitable organizations for neglected areas until his arrival. At his initiative, the city established the "Holy Society for Wood Distribution," a charitable fund aimed at ensuring a steady supply of firewood to heat the homes of the poor during the harsh winter.[23]

The passing of his first wife

[edit]On 12 Adar I 5556 (1796), two months after they walked their daughter to her wedding canopy,[24] his first wife, Glickl, died. Rabbi Akiva Eger mourned her deeply, as he describes in a letter from that time:

My thoughts are confused, my heart is closed, and I lack the strength to settle into anything, and I am only pouring out my words in bitterness of heart... Therefore, my dear friends, if you find any fault in my letter, do not blame me, for a person is not held accountable for his grief.

— Letters of Rabbi Akiva Eger, Letter 149.[25]

He attributed the stomach ailment he suffered from at this time, which stayed with him for the rest of his life, to the grief he felt during this period. To his friends who sought to console him and quickly proposed a new match immediately after the mourning period ended, he responded with a bitter letter revealing the depth of their love:

Do you consider me to be of such cruel and harsh heart that I would rush to find a match during my mourning? Can I forget the love of my youth, my perfect dove whom God granted to His servant...? She was my support in minimizing the Torah of the Lord within me... She watched over me to ensure my weak and fragile body was taken care of, and she shielded me from financial worries so as not to hinder me from serving God, as I now realize, unfortunately, in my many sins... My pain is as vast as the sea, my wound is severe, and darkness has fallen upon my world.[25]

Rabbi Akiva Eger saw her not only as a wife and mother to his children but also as his partner in all matters of service to God and Yirat Shamayim (Fear of Heaven), with whom he often consulted:

Who among the creatures of flesh and blood knows her righteousness and fear of God better than I? – Many times, we engaged in debates about the fear of God until midnight.

— Letters of Rabbi Akiva Eger, Letter 149.[25]

Shortly before his wife's passing, Rabbi Akiva Eger received an offer to assume the rabbinic position in Leipnik after the previous rabbi, Benjamin Wolf Eger, Rabbi Akiva Eger's uncle and mentor, died, leaving the position vacant. The offer remained open until after his second marriage, but ultimately, it did not materialize.[26]

Following his wife's death, Rabbi Akiva Eger contemplated resigning from his rabbinical post:

To find rest, to remove the burden of the rabbinate, and to live as one of the common folk... Besides the fear of issuing halachic rulings, I always feel as if Gehinnom is open beneath me... It is also hard for me to depend on the community for sustenance for no reason, as some might give out of shame and not willingly... I prefer being a beadle in the synagogue or a night watchman, to earn my living from manual labor and study most of the day.

This thought did not come to fruition.[25]

Second marriage

[edit]

After the intervention of his friends and some of the dayanim (judges) of Lissa, Rabbi Akiva Eger remarried at the end of the year, in a second match, to his niece Breindel, the daughter of his brother-in-law, also a son-in-law of Itzik Margolis, Rabbi Yehoshua HaLevi Feibelman Segal, who served as a dayan in Lissa and later as the Av Beit Din in Satmar. Despite the age difference and Rabbi Akiva Eger's concerns about entrusting the upbringing of his children to his young niece, he preferred this match as it brought comfort to his grieving father-in-law. To his brother-in-law, his new father-in-law, he wrote immediately after the wedding about how his children from his previous marriage saw her as their mother in every way and praised her performance:

To my dear father-in-law... Regarding your daughter... may his pure heart be calm and trust, and may he not worry. For her great fear of God and wisdom have enabled her to do all things properly. Despite her young age, she is, thank God, the lady and mistress of the house.

The Lord has shown His great kindness to me, granting me a second match beyond my merit. Even my children see her as a comfort after their mother; they revere and respect her as if she bore and raised them herself, without distinction.

Your son-in-law, your friend, who honors you as a father, Akiva— Letters of Rabbi Akiva Eger, Letter 150.[27]

In 1801 (5561), their first son was born. Rabbi Akiva Eger named him Moshe after his father, who had died about a decade earlier.

In 1802 (5562), after the death of Rabbi Meshulam Igra, the rabbinic seat of Pressburg became vacant, and Rabbi Akiva Eger was among the leading candidates proposed by the local community board, but ultimately, Rabbi Moshe Sofer (the "Chasam Sofer"), who later became Rabbi Akiva Eger's son-in-law, was appointed.[28]

In 1805 (5565), Rabbi Akiva Eger's fourth son was born and named after his uncle and mentor, Benjamin Wolf, the rabbi of Leipnik. Benjamin Wolf Eger (the second) was a learned Torah scholar and resided in Berlin.[29] In 1806 (5566), his daughter Hadassah was born; she later married Rabbi Meir Aryeh Leib HaKohen Rosens of Brody, and after her death (before 1837), he married her younger sister, Beila.[30] In 1807 (5567), his son Feibelman was born but died the following year.[31] Another daughter born to him in Markisch-Friedland was Rodish, wife of Rabbi Wolf Schiff of Wolnstein (d. 1849).[32]

In the summer of 1810 (5570), Rabbi Akiva Eger was offered to leave Markisch-Friedland for the rabbinic position of his hometown, Eisenstadt. A rabbinic contract was sent to him, where the community leaders, aware of the salary issues in the poor community Rabbi Akiva Eger was serving, offered generous terms, including appointing two individuals to oversee the rabbi's livelihood. Rabbi Akiva Eger had already given his consent in principle.[33] However, his friends, the rabbis of the cities Lissa, Berlin, and Rawitsch, prevented him from taking the position, and the appointment did not materialize.[34]

In the summer of 1811 (5571), Rabbi Akiva Eger's mother died in Eisenstadt. Later that year, a daughter was born to him, named Gitel after his mother. She later married Rabbi Shmuel Kornfeld.[32] A year later (1812), his young son-in-law, Rabbi Avraham Moshe Kalischer, who was then the rabbi of Schneidermuhl, died, leaving Rabbi Akiva Eger's daughter, Sherel, aged 22, with their two daughters: Glickl (who died in childhood) and Radish (wife of Rabbi Yosef Gins).

Rabbi Akiva Eger urgently wrote about her in a letter to Rabbi Moshe Sofer, the rabbi of Pressburg, asking if he knew of a suitable widower in his community for his daughter. Rabbi Sofer, who had recently been widowed from his first wife, forwarded the letter to his close associate, Rabbi Daniel Proshtitz, who then wrote to Rabbi Akiva Eger, suggesting he match his daughter with the rabbi of Pressburg. At the same time, Rabbi Bonem Eger, Rabbi Akiva Eger's brother and the rabbi of Mattersdorf, reached out to Rabbi Sofer, his friend, and to his brother, Rabbi Akiva Eger, supporting the match idea.[35] The wedding took place in early winter of 1813 in Eisenstadt.

Rabbi Akiva Eger's friendship with his son-in-law, the Chasam Sofer, began even before they became family through marriage, as they exchanged letters on halachic and communal matters. The age gap between them was less than a year: Rabbi Akiva Eger was born in October 1761, while the Chasam Sofer was born in September 1762. A popular legend highlights the sensitivity of Rabbi Akiva Eger towards others’ feelings, portraying his character as compassionate. This story takes place during a meeting between Rabbi Akiva Eger and two other Torah giants of his generation: his son-in-law, the Chasam Sofer, and Rabbi Yaakov Lorberbaum of Lissa, author of "Netivot HaMishpat." The legend, while elevating Rabbi Akiva Eger's status as a wonder worker, also shows the near-blind reverence people held for him: During this meeting, the two rabbis visited Rabbi Akiva Eger's home. Pleased with their visit, Rabbi Akiva Eger invited them to dine with him and assigned one of his yeshiva students to serve the meal. During the meal, the rabbi of Lissa shared a complex discussion involving several Talmudic topics. When he finished, Rabbi Akiva Eger asked his son-in-law for his opinion, and the Chasam Sofer expressed, at length, his view that the rabbi of Lissa's argument was untenable. Sensing that the rabbi of Lissa was displeased with the turn of events, Rabbi Akiva Eger, in his sensitivity, asked the student serving as a waiter for his opinion on the dispute between the two rabbis. To everyone's surprise, the student declared that the rabbi of Lissa was correct, outlining the points of disagreement, refuting the Chasam Sofer's position, and proving the truth of the Lissa rabbi's argument. According to the legend, the Chasam Sofer later remarked that the student's arguments were beyond his Torah knowledge and that it was unlikely he could have followed the discussion while serving the meal.[36] However:

When my father-in-law commands someone to speak, even a stone from the wall would cry out.[36]

Immediately after his wedding, the Chasam Sofer began searching for a rabbinic position for his father-in-law in a major city befitting his stature and standing in the Jewish community. One proposal was for the rabbinate of Trešt (Třešť), Moravia. For an unknown reason, Rabbi Akiva Eger was not chosen for the position, and the community of Trešt decided to appoint Rabbi Elazar Löw, author of "Shemen Rokeach."

Rabbinic position in Posen

[edit]

In 1812, Jews of Prussia received formal emancipation. The process of secularization that followed the "Age of Enlightenment" was felt more strongly in smaller towns, and the 51-year-old Rabbi Akiva Eger began to question his influence over the local Jewish community, particularly the youth. He started reconsidering the idea of stepping down from the rabbinate altogether and became more open to rabbinic offers from other communities where his Torah abilities could be more effectively utilized. In the following years, negotiations took place with several cities regarding his tenure.

The offer of the Posen Rabbinate

[edit]In the month of Adar 5574 (1814), Rabbi Akiva Eger was offered the rabbinic position of the large city of Posen, then under Prussian control (in German: Posen; in Polish: Poznań; now in Poland, capital of the Greater Poland region, Wielkopolska). The last rabbi of Posen had died seven years earlier, in 1807, and the community had been without a spiritual leader. Disputes within the community leadership, mainly of a religious nature, had emerged, with liberal and Haskalah members wanting to appoint a more progressive rabbi. However, they faced opposition from the religious officials and others who did not want to forgo appointing a rabbi of well-known Torah stature, believing such a choice would honor the community. In the winter of 1814, an opportunity arose for the appointment following a coalition of relatively conservative factions within the community. In a meeting held at the home of Rabbi Yosef Landsberg, the head of the yeshiva in Posen, it was decided to appoint Rabbi Akiva Eger of Markisch-Friedland.[37] One opinion suggests that the debate surrounding the appointment of Posen's rabbi was primarily fueled by the political-national tensions in the region. Posen, historically Polish, had been under Prussian control since 1795. Some believed this was temporary and preferred appointing a Polish-born rabbi who could interact effectively with the authorities, while others assumed Prussian rule would persist (as it did) and therefore preferred a German-born rabbi for the same reason. According to this view, Rabbi Akiva Eger's appointment was a compromise.[38]

Delegates from the community board came to Rabbi Akiva Eger's home, but he hesitated and refused to immediately take on a responsible position in a large city like Posen. In his letter to the community board, he requested time to decide and promised to respond either positively or negatively before Passover. Meanwhile, news of the proposed appointment spread in Posen, causing unrest among some Jews in the city who argued that the appointment of an "old-fashioned" rabbi like Rabbi Akiva Eger was unsuitable for a progressive community like Posen's. Twenty-two community members lodged a complaint with the local governor, Zbroni di Sposeti, arguing that Posen needed only a preacher who would focus on ethics and moral rectification. The community board tried to defend itself by claiming that since the election process was legitimate, the rest was a private matter of the Jewish community. However, to no avail; the authorities enforced new elections.

Rabbinic offers from smaller towns due to the political struggle in Posen

[edit]Even as it became public knowledge that the important and leading community of Posen, the most significant in Western Poland annexed to Prussia (since 1793), had chosen Rabbi Akiva Eger as its rabbi, the delay in the appointment led Rabbi Akiva Eger to receive offers from smaller communities, such as the community of Wilen.[39] This caused discontent among the local community in Markisch-Friedland, which could have accepted the rabbi's move to a more prestigious position—a common career path for rabbis at that time—but not a move to an equivalent community. At the beginning of the month of Shevat 5575 (1815), several Jews of Markisch-Friedland approached Rabbi Akiva Eger on the matter, and he replied:[40]

I do not wish to leave here for the sake of money or honor, for I lack neither. But troubles are beginning here, and unfortunately, I am distressed by this, and I am fifty-three years old... and here they do not raise children for Torah... and there is no difference between a small community and a large one. And if, God forbid, it is false honor that I seek?

As the delays continued in Posen and the knowledge that Rabbi Akiva Eger had grown tired of his long tenure in Markisch-Friedland spread, the community of Kornik, a small community of about 1,000 Jews in a small town of approximately 3,000 residents,[41] tried its luck and sent Rabbi Akiva Eger its own "rabbinic contract" on the 18th of Shevat 5575.[42][41] It is possible that the Kornik community board assumed that Rabbi Akiva Eger had become tired of Markisch-Friedland's rabbinate but was not yet ready for a large rabbinate like Posen. The financial conditions offered in the Kornik contract were more generous than those in Posen.[41] Rabbi Akiva Eger ultimately declined Kornik's offer for unknown reasons and accepted Posen's offer in the spring, despite the ongoing internal dispute within Posen.[43][44]

Compromise agreement and acceptance of the Posen Rabbinate

[edit]In the summer of 1815 (5575), as preparations for new elections for the rabbinate in Jewish Posen were underway, negotiations took place among the conflicting factions within the community. Ultimately, in a meeting attended by all parties and mediated by Rabbi Yaakov Lorberbaum of Lissa, who came as an agreed-upon arbitrator, even those who had initially opposed Rabbi Akiva Eger's appointment agreed to it.

Thus, Rabbi Akiva Eger's appointment was delayed until the month of Elul 5575. In the rabbinic contract sent to Rabbi Akiva Eger in this month, it was written:[45]

Rabbinic Contractב"ה יום ה' ב' אלול בא יבא אדמ"ו הגאון מ"ו עקיבא איגר לפ"ק עיר הקודש ק"ק פרידלאנד משם רועה אבן ישראל קהלת קודש פוזנא תשית לראשו עטרת פזנאה עיר ואם בישראל יושבת ק"ק פוזנן צהלי ורוני כי גדול בקרבך קדוש ישראל ברוך אשר לא השבית גואל מישראל איש אלקים קדוש ונורא מאוד תפארת ישראל ה"ה אדמ"ו הרב הגאון הגדול המפורסם מופת הדור החרוץ ושנון נזר הקודש פאר הזמן נ"י פ"ה ע"ה כ"ש תפארתו מ"ו עקיבא נרו יאיר, כאור הבהיר.

When the leaders of the people gathered together, uniting the tribes of Israel, on the night of the 21st of Adar 5574, to oversee communal affairs and the needs of the Jewish people, here in the Holy Community of Posen, all the elders, the distinguished rabbis of the holy community, the leaders of Israel, the elders of the congregation, and the great luminaries, those who sit in judgment and serve as judges in Israel, came together. When the assembly convened, the eyes of the congregation, the noble leaders, the scholarly notables, those whose ancestral merits assist them and whose righteousness is as enduring as the mountains, and the rest of the holy congregation—those called forth and people of great repute among the Jewish people—spoke to one another, fearing that God’s congregation had become like a flock without a shepherd. They said: Let us appoint a leader, a faithful shepherd, to lead the people with warmth, to teach the people the laws of God and His teachings, so that they may know what to do in Israel. Let us seek a man who possesses the spirit of God, the spirit of wisdom and understanding, a heart that listens to judgment, one who is both a teacher and a guide. And one of the assembly members stood up and said: Behold, a holy and righteous man, perfect and a solver of mysteries, dwells in the Holy Community of Markisch-Friedland, and his name is Rabbi Akiva Ginz. His reputation has spread across the lands, and his fame is recounted in the isles. Let us call upon this man of God to be the leader of God in our midst, to be our rabbi and teacher, a light for the people and a guide on their path, one who will do the righteousness of God and uphold His judgments among Israel. The people responded with one voice and said: This is good, for we know the man and his ways; he seeks the welfare of his people and is a great man among the Jews. He is the chosen one, and upon him shall the crown of the rabbinate rest. However, we will only agree if he consents to uphold the conditions outlined in our records, as discussed with previous sages. These are the details...

These matters were agreed upon on the day of the assembly, and the conditions were written according to the main points for the distinguished sage mentioned above. He accepted and confirmed to be our rabbi and teacher according to these conditions, like the previous sages. The people rejoiced and sounded the trumpets, saying: Long live our master! May he come to our congregation with joy, and may our hearts be glad, and our souls rejoice. We give thanks and praise to our Creator for all the goodness He has granted us, and great goodness for the House of Israel. We give thanks for the past and pray for the future: May it be His will that our master and teacher will arrive at an auspicious time for our eternal success. With all this, we make a covenant, and the signatories are our leaders, priests, officers, distinguished rabbis, and the prominent figures, all bound together by the ties of love.

Those who have signed below in accordance with the passage "so that he may lengthen his days in his kingdom, he and his children, in the midst of Israel," here in Posen(- the signatures of 133 distinguished members of the community) We, too, the distinguished officers, have signed below and delayed until now so that this list may serve as a testament that all the above signatories are truly living witnesses. Done on the eve of Shabbat Parashat Shoftim, the 3rd of Elul 5575

(- 28 signatures, including the signatures of the community leaders)

In the year 5578 (1818), his son Shmuel was born; he later resided in Minsk after his marriage. In 5581 (1820 or 1821), his son Rabbi Simcha Bunim Eger of Breslau (who died in 5628, 1868) was born.[46] A scholar who spent his last twenty years in Brezan, Galicia, his father's book "K'tav Ve'Hotam" was printed from his manuscripts. In 5582 (1822), his daughter Beila was born. After the death of her older sister Hadassah, she married her brother-in-law Rabbi Meir Aryeh Leib HaCohen Rosenz from Brody.[47] Two years later, in 5584, his son Rabbi David Eger of Breslau was born. In 5587 (1827), his daughter Yitta was born (she died in 5641, 1881); she married Shimon Berliner. Other daughters born to him in Posen include: Freida (Freidke) (who died on the first day of Passover 5637[48]), wife of Rabbi Simcha Ephraim Fishel Gertshtein (Gradstein) of Lublin, who was also the brother-in-law of Rabbi Akiva Eger's grandson Rabbi Leibele Eger. And Rivka Rachel (?–5649, 1889), wife of Rabbi Chaim Shmuel Birnbaum of Dubno, author of the books "Rachash Levav" and "Maaseh Chashav".[49]

Even in Posen, he simultaneously served as the head of the yeshiva while holding the rabbinate. His tenure in Posen lasted approximately 23 years until his death.

His daily schedule

[edit]During his twenty-three years in Posen, he maintained a strict and fixed daily schedule: he woke up at 4:00 AM, studied Mishnah until 6:00 AM, and then delivered a one-hour lesson to a group of laymen at the synagogue before the morning prayer, which he allotted an hour for. Between 8:00 and 9:00 AM, he ate breakfast at home with his family; his meal always consisted of one cup of coffee without sugar. After breakfast, he studied Tanakh until 10:00 AM, and from 10:00 to 11:00 AM, he delivered his daily lesson on Talmudic topics, dedicating the following hour to reviewing what was learned.

No time was allocated for lunch, and a bowl of soup was served to him while he delved into the Gemara open before him. Between 1:00 PM and 2:00 PM, he rested on his bed, armed with a pencil, while reviewing new books brought to him and annotating the margins.

From 2:00 PM to 4:00 PM, he sat as a judge in the community's court, and the community board meetings were scheduled during these hours to allow his participation, taking place in the courtroom. After the court proceedings, which usually ended before 4:00 PM, he drank a glass of wine, adhering to the halachic ruling that a judge should not issue rulings after drinking wine. He then visited community members, comforting the sick and consoling mourners, a task that often took a long time due to his commitment to visiting individuals from all societal layers. This practice ceased over the years as his communal duties increased. He found a halachic solution to the obligation of visiting the sick by hiring a special messenger who visited the sick on his behalf and provided detailed reports on their medical conditions.[50]

At 4:00 PM, he prayed Mincha (afternoon prayer), which he set at this relatively early time to maintain a consistent schedule even during the winter, when sunset occurs earlier. He used to pray the afternoon prayer wearing tefillin. After Mincha, he delivered a halachic lesson from the book "Magen Avraham," until the Maariv (evening prayer).

The hours from 8:00 PM to 10:00 PM were dedicated to reading letters sent to him from across the Jewish diaspora in Europe and beyond and responding to them. Afterward, he studied until midnight, then he would go to sleep.[51]

Public activities in Posen and Its vicinity

[edit]That Rabbi Akiva Eger was a seasoned activist in communal matters, sowing righteousness, avoiding honor, and truly despising the rabbinate in its most literal and plain sense—this we do not know from his responsa, nor from his "Talmud Margins," but from what is told about him among the people. -Mordechai Lifshon, Introduction to the Book "Medor Dor"

As the rabbi of Posen, Rabbi Akiva Eger exercised his rabbinic authority even in non-halachic matters when it was necessary for the public's welfare. In 1831 (5591 and the beginning of 5592), during the outbreak of the cholera epidemic, Rabbi Akiva Eger instituted several regulations that significantly helped prevent the spread of the epidemic and isolated the affected areas: he appointed a committee responsible for overseeing hygiene in public spaces and raising awareness among the residents. He ensured that the committee funded cleaning services for the homes of the poor and distributed proclamations in the name of religion about the obligation to safeguard health by boiling drinking water and maintaining personal cleanliness. To reduce mass gatherings, a significant vector for disease transmission, the rabbi decreed that it was permissible to forgo prayers in a quorum. As the High Holy Days approached that year, he decreed that a lottery be held to determine which community members would pray in the synagogue during the Rosh Hashanah prayers and which during Yom Kippur, thus reducing the number of attendees to one-third. He significantly shortened the prayers themselves and scheduled a long break between each prayer. In cooperation with the local police, officers were stationed in the synagogues to monitor order and prevent crowding during entry and exit times. He required all congregants to drink a hot beverage before morning prayers, despite the custom not to eat or drink before prayer, and canceled the traditional gathering for charity collection on the eve of Yom Kippur.[52] His efforts significantly reduced the number of casualties in Posen during this cholera outbreak, earning him a letter of gratitude from Frederick William III of Prussia.[53]

Rabbi Akiva Eger was very active in the Jewish public sphere both in Posen and beyond, involved in numerous cases affecting the lives of Jews in Prussia and Poland. Below are some of the major cases he managed:

The residency permit issue for the Rabbi of Lissa

[edit]In Adar Sheini 5581, Rabbi Yaakov Lorberbaum, the rabbi of Lissa and author of "Netivot HaMishpat" and "Chavat Da’at," was forced to leave his city due to his divorce case, which could only be resolved in Galicia. He planned to stay in Galicia for a year and return to his city, but fearing that those within the community who opposed him might take advantage of the situation to replace him, a contract was signed between him and the Jewish community leaders to ensure his return to the rabbinate when the time came. This contract was signed under the intervention of Rabbi Akiva Eger, who, despite the severe cold at the time, traveled to Lissa to facilitate it, and it was entrusted to him. For technical reasons, Rabbi Lorberbaum did not arrange for an official exit permit. Later, a problem arose when his opponents within the community proposed a resolution to reduce his authority and salary, and under these conditions, he decided he was released from his obligation to return to the Lissa rabbinate. Rabbi Akiva Eger engaged in extensive correspondence with both parties to try and reach a compromise.[54] The negotiations ceased when, in March 1823, the district head, possibly following a denunciation, issued an order banning Rabbi Lorberbaum's return to the city on the grounds that he was a foreign citizen. The fact that he sold his possessions before traveling to Galicia was used against him as evidence that he left the city with no intention of returning. The opposition in the Lissa community to his return, and the appeals under Rabbi Akiva Eger's close guidance to the regulator regarding the revocation of citizenship, continued. In June 1825, the representative of the Prussian government in Posen issued a final ruling that Rabbi Lorberbaum could not be allowed back as he was a foreign citizen. Later appeals on this matter were dismissed outright. Rabbi Akiva Eger eventually gave up, and the rabbi of Lissa did not return to his position.[55]

The Jewish hospital named after Latz

[edit]

In 5591 (1831), Rabbi Akiva Eger was appointed as the executor of the estate of the Jewish philanthropist Solomon Benjamin Latz, who had died. At the request of Rabbi Akiva Eger, the deceased dedicated a large sum of his fortune for the establishment of a study hall and a hospital for the Jewish community in Posen. In the official appointment document, it was stated that two-thirds of the funds would be used for building the hospital and its initial operation, while one-third would be allocated for the construction of the study hall. The philanthropist, fearing corruption, ensured that the community leaders would have no right to intervene in the affairs of the institutions and would not receive any benefit from them. He appointed Rabbi Akiva Eger as the sole trustee of the institutions, stating:

"I rely on the rabbi's great fear of God, his Torah knowledge, and integrity, so that his will would be considered as my own."

Using the estate funds, Rabbi Akiva Eger purchased a large residence, and with an additional donation from the donor's son-in-law and other funds that he borrowed himself, he inaugurated the hospital under the name "Beit Shlomo" after the benefactor. The hospital wing contained 13 patient rooms, and one hall was dedicated as a study hall for Torah learning and prayer. Additionally, a pleasant garden was maintained in front of the building.

Rabbi Akiva Eger personally supervised the hospital's management and wrote its operating regulations. The hospital provided medical care to hundreds of patients annually at a reduced cost, and those with limited means received free treatment and hospitalization. Wanting to distance the Jewish community leadership, which he suspected of being influenced by the Haskalah, Rabbi Akiva Eger ensured the institution's funding came from philanthropists rather than the local community funds. This move provoked the community leaders, who appealed to the authorities to enforce a clause in the law stating that all Jewish institutions in the city should be under the governance of the community leadership. The rabbi defended himself by stating that according to Latz's will, the institution, built with his funds, could not be placed under the community leaders’ control, and he invited the authorities to send an inspector to the institution. The inspector's examination revealed that the institution was managed according to regulations and that there was no suspicion of embezzlement of public funds. The inspector concluded with a recommendation that the authorities reprimand the community leaders for their petty complaint. Later attempts at mediation proposed by the community leaders, which involved signing an agreement to change the institution's regulations after the rabbi's death, were rejected. In practice, the regulations were preserved even after the rabbi's death, and even after "Beit Latz" was repurposed as a retirement home for the community[56]

The appointment controversy of Baruch Lifshitz to the Rabbinate of Wornik

[edit]

In the summer of 5593 (1833), Rabbi Akiva Eger led a principled struggle that had nationwide implications for Poland, Germany, and the Jewish diaspora in general. The background of the controversy was his long-standing friendship with one of the central figures in the affair, a friendship that continued even after the controversy, despite the harsh exchanges that accompanied it. In the month of Sivan that year, Rabbi Yisrael Lifshitz, one of Germany's leading rabbis and author of the popular yet deep commentary on the Mishnah, "Tiferet Yisrael," attempted to appoint his son, Baruch Yitzchak Lifshitz, as rabbi of the town of Wornik (Wronki), despite his being unmarried and young. Rabbi Akiva Eger opposed the appointment of unmarried men to rabbinic positions, which involved daily interaction with all segments of the Jewish population, regardless of gender. This case was particularly problematic since the young Rabbi Lifshitz was a native of Wornik and well known there. Despite his long and positive relationship with the Lifshitz family, Rabbi Akiva Eger opposed the idea, fearing it would set a precedent, especially considering the general religious situation in Europe at the time, that could serve reform advocates seeking to appoint talented young individuals who were not yet experts in or experienced with halachic rulings.

Rabbi Akiva Eger threw his full public weight into the matter. In his letter dated the 3rd of Tammuz (June 20), he addressed Rabbi Lifshitz senior, who was then the rabbi of Khadzyets, demanding that he cease his lobbying efforts and withdraw his son's candidacy. In the absence of voluntary compliance by the Lifshitz rabbis, he wrote:

“If necessary, I will oppose this and do what I can to annul it”.

Rabbi Lifshitz's response is lost, but from Rabbi Akiva Eger's reply dated the 14th of Tammuz (July 1), it is clear that he reiterated his stance, emphasizing that he would not allow the young Rabbi Lifshitz to issue halachic rulings in Wornik at all, not even temporarily or on simple matters. Two days earlier, he sent a personal letter to the young Rabbi Lifshitz, opening it without the rabbinic title “To Mr. the bachelor Baruch, son of the rabbi of Khadzyets”, instructing him not to issue rulings in Wornik even on minor issues, emphasizing that conducting wedding ceremonies was also considered issuing a halachic ruling in this context, and was thus forbidden to him.

In parallel, he wrote to the town's shochet instructing him not to bring any kashrut questions regarding animals or poultry before "the bachelor Baruch Yitzchak" and not to allow him to check the slaughtering knife or examine it under his supervision. In additional letters to the Wornik community board and the rabbis of neighboring towns, he emphasized that he had no personal interest in the matter, that his sole intention was for the sake of Heaven, and he requested that the regional rabbis join him in a ruling that unless the new rabbi passed an examination before the regional rabbis, himself included, he was not permitted to issue halachic rulings, and meat from his community should not be consumed.[57]

In later years, Rabbi Baruch Yitzchak Lifshitz became a preacher in Hamburg and authored several books. His prominent work is his notes on his father's Mishnah commentary "Tiferet Yisrael," which he signed: Avi—an acronym for "Amar Baruch Yitzchak" (said Baruch Yitzchak).[58]

A processed detail from the painting by Julius Knorr The Market Area in Posen[2]

His passing

[edit]In 5592 (1832), his daughter, Sarah, wife of the Chatam Sofer, died at the age of 44. Due to his advanced age and concerns for his health, his son-in-law ensured that Rabbi Akiva Eger was not informed of the tragic news.[59] According to N.M. Gelber, Rabbi Akiva Eger was chosen for the Rabbinate of Vilna in his final year but did not accept the invitation.[60]

In Elul 5597 (1837), Rabbi Akiva Eger fell seriously ill. A slight improvement occurred during the Ten Days of Repentance of 5598, and he appeared for public Yom Kippur prayers. However, the day after Yom Kippur, he developed a severe pneumonia, and three days later, on the 13th of Tishrei 5598, he died in Posen at the age of 76. He left behind fifteen children, several of whom from his second marriage were still unmarried at his passing. His last wife had died a year before him, leaving their children orphaned. In his will, he allocated a certain sum for their wedding expenses.

Upon the news of his death, the local Jewish leadership declared a "work cessation," a general order to close shops and businesses to pay last respects to such an important figure. The entire Jewish community of Posen attended his funeral, along with members of the city's upper non-Jewish classes, government officials, and the bishop of Posen.[61]

According to his will, Rabbi Akiva Eger was eulogized only at the gravesite, rather than at the start of the funeral procession as was customary. The will was publicly released a few days after his passing, wherein Rabbi Akiva Eger forbade his students from eulogizing him and asked that they study in his merit during the year of mourning and on the anniversary in the following years. The text of the will was published in German in the Jewish press:

Obituary: Our good and God-fearing father, Chief Rabbi R' Jacob Moses Akiva son of Moshe Eger, was called by the righteous will of the good and beneficent to all, on the 13th of Tishrei from his earthly life to a better one. We announce this to his friends and admirers, and especially to his students and colleagues, attaching a portion of his will as follows: "Upon my death, my students and colleagues should be notified through public newspapers, along with my request that for my merit they study one chapter of Mishnah each day during the first year, and on my yahrzeit thereafter. Besides this, I request that I not be eulogized in any place other than at the burial site." Posen, 18th of Tishrei 5598.[62]

Rabbi Akiva Eger also specified the exact wording he wished to be inscribed on his gravestone to prevent any honorific titles that did not align with his modesty during his life. The gravestone inscription according to his will:

Here lies the rabbi R' Akiva Eger, servant of God's servants in the Holy Community of M. Friedland and the Holy Community of Posen, gathered to his people on...

The community members, wanting to honor their rabbi who, in their view, had humbly downplayed his own status, took the liberty of interpreting the abbreviation R as standing for: Rabbi Rabbenu Akiva Eger. The original gravestone of Rabbi Akiva Eger in the Jewish cemetery of Posen was destroyed during World War II, and afterward, a new marble gravestone was placed at the assumed location of his grave, now situated within a residential street, with the inscription quoting the old gravestone.

Despite Rabbi Akiva Eger's directive against being eulogized after his death, fearing that future generations might interpret it as neglect or disregard, one of his students published a mournful poem titled "Unique Mourning",[63] explaining that by doing so, his rabbi's words were being observed in letter, if not in spirit. A rhymed passage from the poem's introduction justifies the act of eulogy, reflecting the shock and silence that struck the Jewish world upon Rabbi Akiva Eger's passing:

(Głogowska Street)

Rabbi Akiva Eger's gravestone is on the bottom left row

The top of the gravestone reads: "...which is buried here or near this location"

And if His holy word binds me in chains -

To lament him and weep, his humility restrains me, I have not walked in greatness, and I am a man of uncircumcised lips, And I fear lest my tongue sin to break his command - Shall I guard my mouth with restraint, heed his injunction? Shall I be silent, restrain myself, give my eyes respite? Shall I say to the sun: still! To the sea, restrain your wrath? Shall I stand as a beacon of light, and darkness envelops me?

Fire has struck the forest, the flame has fallen on the cedars, And the wall-moss shall stand steadfast? The shepherd has been taken from his flock, and the sheep remain silent? The father has gone and is no more, and his sons keep silent and betray? Alas, this generation is like a deaf viper! There is no God in its camp! So shall the next generation say, astonished and amazed: The Ark of God has been taken, and no one seeks it! Their eye's delight has been despoiled! And they stand and watch!

Shall I, too, remain silent? Shall my tongue cleave to my palate? Shall I remain silent for my fruit? Silent for my teacher and guide? Let me speak and find relief! Let my tears fall freely! May I find healing for my sorrow, and through my lamentation, find a remedy! Would that my voice would cry like a shofar, reaching the gates of death; Who pressed the bowstring and made the righteous the target? I will carry my grief to the distant, my mourning to the close; Let a friend stand by my sorrow, and a brother be born for adversity!

So, let my harp not remain silent! Proclaim the news! Mourn this lamentation, even if your strings falter! Bear witness to us that the great and terrible mourning is real, And let the ends of the earth know the wail of your strings! Be strong and brave! Do not be ashamed to tread the gate, And let every eye be filled with tears, and every heart mourn, And if your voice weakens, even in the wilderness, in the forest,

Even the sigh of the suckling child will be heard like a shofar!

Additional mourning pamphlets were printed and circulated after his passing, including:[64]

- Zechor Tzaddik (Breslau 5598), in Hebrew and German, by R' Mordechai Levenstam.

- Kol Bochim (Krotchin? 5598), by his student Rabbi Yisrael Goldschmidt, rabbi of Krotchin.

- Ayen HaMayim (Breslau 5599), the book's title page states:

The book contains the sermon of Rabbi Avraham Dov Pelham from Meziherich.It is a great mourning and bitter eulogy on the passing of our master, our teacher, the rabbi of all the diaspora, the gaon, the true saint, our master Akiva Eger.

- G'zei Yesishim (Vilna 5605) by R' Chaim Krinsky.

- Rashfei Keshet (Koenigsberg 5612) by Rabbi Avraham of Stavisk.

On behalf of the community, it was announced at the sealing of the grave that his son, Rabbi Shlomo Eger, who until then served as the rabbi of Kalisz, would be his successor as the rabbi of Posen[65]

His views

[edit]

Attitude towards the Maskilim and Reformists

[edit]Rabbi Akiva Eger was among the leading rabbis opposing any change or reform in the religion, holding that even the yod of the earliest authorities’ words should not be deviated from. In his response published in the compilation "Eleh Divrei HaBrit" against the first Reform synagogue, he argues:

If we allow ourselves to annul even a single letter of the words of the Sages, then the entire Torah is at risk.

Many of his actions in the rabbinate and his appointments of rabbis in the cities of Prussia were driven by his opposition to reformation, and he often acted with the explicit aim of preventing the appointment of Haskalah rabbis.

The writer Alter Druyanov recounts, based on the historian Shaul Pinchas Rabinovitch (Shapir), Rabbi Akiva Eger's encounter with the students of the Rabbinical Seminary of Warsaw and his sarcastic remarks towards them:

Rabbi Akiva Eger came to Warsaw and went to see the Rabbinical Seminary, founded there in 1826. He examined the students and found them lacking in Talmudic and Halachic knowledge.

He wondered and asked the principal: - Where is the Torah of these students? The principal replied: - This seminary is merely a kind of corridor to prepare the students for rabbinical studies. Rabbi Akiva responded:

- It seems that a student who studies here is generally an "erev rav" (mixed multitude).[66]

Despite the above, when modernity was possible or necessary within Orthodox boundaries, he did not oppose it. His disciples were the first among Orthodox rabbis to introduce the practice of delivering speeches, sermons, and eulogies in German, considering it a practical adaptation to the language of their listeners and not a remnant of modernity. During his lifetime, in 1821, his disciple Rabbi Shlomo Plessner delivered a eulogy in modern German for Rabbi Avraham Tiktin of Breslau, and since then, this practice gradually became accepted among all German Orthodox rabbis.[67]

Attitude towards Hasidism and its leaders

[edit]

Rabbi Akiva Eger's attitude towards the Hasidim and the Hasidic movement was moderate, although he remained faithful to the 'opposing' worldview, which rejected the movement and, at times and places, even excommunicated its supporters.[68] Evidence supporting Rabbi Akiva Eger's moderate attitude towards Hasidism can be found in a letter from Rabbi Eger's son-in-law, Rabbi Shmuel Chaim Birnbaum, to his nephew Rabbi Yehuda Leib Eiger of Lublin, where he describes, in response to his inquiry, details of daily life in his grandfather's home, mentioning among other things the books used:

The Shulchan Aruch from the Vilna Gaon was among the rabbinic books, as was the Tanya from Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, of blessed memory. I cannot recall if the Shulchan Aruch HaRav was among his many books...

— Iggerot Sofrim, p. 56

Before 1805, while still serving as rabbi in Markish-Friedland, the Hasidim spread a rumor that he leaned towards Hasidism or had even joined the movement. Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Lipshitz, the "Chemdat Shlomo," refuted this rumor in a letter to his son.[69] In retaliation, a rumor spread from the opposing camp that Rabbi Akiva Eger had issued a harsh letter against Hasidism and the Hasidim. The Rebbe Rabbi Dovber Schneuri, the "Mitteler Rebbe," leader of Chabad, in his letter to his nephew, son-in-law, and successor the Tzemach Tzedek of Lubavitch, recounts his meeting with Rabbi Akiva Eger in 1825.[70] Rabbi Akiva Eger denied authorship of the harsh letter attributed to him. He wrote:

…And I recounted to him some of the division and baseless hatred between the Mitnagdim and Hasidim according to their tradition from the Gaon of Vilna, and it seems that Your Honor seeks the welfare of all his people equally, and he raised his hands and said: Heaven forbid, all of Israel are friends... And it is a lie that I wrote any letter against Hasidim, for the opposite... and we parted in peace and great honor."[71]

His work

[edit]Editing of the Responsa

[edit]

Since the publication of his responsa began during his lifetime, his instructions have been preserved, some of which are technical, regarding the printing of his works. He addressed questions generally related to the entire genre of responsa literature, such as the issue of editing versus fidelity to the original letters, and the question of the standard honorific titles, which were often filled with exaggerated superlatives.

In his letter from Kislev 5593 (winter of 1833) to his son Abraham, he instructed not to duplicate responsa he had written to different people on the same topic, even if some contain additions and innovations. He stated,

"It is not worthwhile to tire the reader's eyes for a small addition,"

and preferred to edit the central responsum and incorporate later additions within it,

"and there is no harm to the inquirer if, after the response to him, something is added."

He also addressed the question of the quality of the printing, the paper, the ink, and the font, as he believed that the aesthetics of the print, seemingly external, had an impact on how the text was perceived by the reader. In one of his letters, printed by his sons in their introduction to the book of responsa, he expressed:

"I ask you, my dear son, to supervise that it is printed on fine paper, with black ink and proper letters. In my opinion, the soul is moved, the mind is comforted, and the intention is awakened through study in a beautiful and adorned book, and the opposite occurs if the print is blurred."

Regarding the standard honorific titles typically included in such letters and usually copied verbatim into printed responsa literature, he strongly rejected the practice, preferring that no titles, even minimal ones, be quoted:

"To the writer, it is flattery, and to the recipient, it is either arrogance if he is praised too much or baseless hatred if praised too little. I detest them so much that I have resolved not to look at them or read them, much less desire them in a printed matter meant to last for many years, lest I be ridiculed in the world of truth."

Editions of the Responsa

[edit]The first edition of "Responsa Rabbi Akiva Eger," known as the "First Edition," was printed by his sons in Warsaw in 1835, followed by an edition in Stettin (1862), and later in many reprinted facsimiles. In 1889, an additional collection of Rabbi Eger's responsa was printed in Vienna under the title "New Responsa of Rabbi Akiva Eger," which also received numerous reprinted facsimiles. Over the years, additional collections of responsa were published from time to time. In the early 21st century, several editions compiling all previously printed responsa were published in several volumes. Simultaneously, the original collection, the "First Edition of Responsa Rabbi Akiva Eger," received several annotated editions.

Talmudic Novellae and margins of the Talmud

[edit]

In addition to the extensive responsa literature published from Rabbi Akiva Eger's writings, publishers have released collections from his writings and those of his disciples, focusing on commentary and insights on the Babylonian Talmud systematically, and on selected topics within it, such as the book "Derush V’Chiddush" published by his sons shortly after his passing (Warsaw 1839) on certain tractates. Additionally, many of his halachic responsa expand during discussions into elucidations of Talmudic topics, sometimes focusing solely on Talmudic analysis without any practical halachic implications, such as exploring the understanding of Tannaim or Amoraim whose opinions were in the minority and were not adopted as the final ruling. Such responsa were gradually collected and organized for the convenience of scholars according to the order of the Talmudic tractates. Additionally, many of his individual notes on Talmudic topics have appeared and continue to appear from time to time in various Torah journals.

Since many of these novellae collections were not organized according to the Talmud's order, and due to the multitude of collections that made it difficult for scholars to follow all of Rabbi Eger's insights on a given topic, there arose a need for a project that would arrange all of his numerous writings according to the order of the Babylonian Talmud. Such a project encountered many difficulties due to issues of copyright, held by numerous entities, and it also required a scholarly authority to guide the work.

From the early 1980s, several editions of Rabbi Akiva Eger's novellae on the Talmud were published according to this vision. The oldest among them is the "Zichron Yaakov" edition, printed between 1981 and 1983 in four volumes, which has since received numerous reprints. This edition has become the standard and popular edition of Rabbi Eger's novellae due to its smaller number of volumes and their compact size. At the beginning and end of each volume, indexes of sources were printed to maintain minimalism within the text pages and not to overload information.

A highly expanded edition, covering even relatively minor references from Rabbi Eger, began to be published in 1990 under the editorship of Rabbi Shlomo Arieli. In this edition, a separate volume was dedicated to each tractate, and some tractates were divided into two volumes. Although this project was not completed, it provided Rabbi Eger's insights on most tractates studied in yeshivot. Another edition in this style, called "Torat Rabbeinu Akiva Eger," was edited by Rabbi David Metzger (Maor Institute, 2005), and it consists of six volumes.

Margins of the Talmud

[edit]Rabbi Akiva Eger used to write brief notes on the margins of the Talmud pages he studied. He also added references and cross-references to topics relevant to understanding the local issue or its contradictions. His notes were first printed in the Prague edition of the Babylonian Talmud published in 1830–1835, titled "Annotations and Cross-References by Rabbi Akiva Eger, Rabbi of Poznań," and later with additional material in the printings of Rom Press and Horodna (1835–1854), eventually becoming known as the "Glosses of Vilna Talmud". The brief nature of these notes often means they require interpretation to fully understand his intentions.

In recent years, a fully annotated edition of Rabbi Akiva Eger's glosses has been published, which organizes and expands upon his notes according to the full text. An annotated edition of the glosses on selected tractates was also published. Research into these annotations has been conducted by Rabbi Chaim Dov Shavel, who partially published his findings in his book "The Teachings of Rabbi Akiva Eger in the Glosses of the Talmud" in 1959 (covering parts of Seder Moed). He continued his research on Rabbi Eger's glosses for all of Seder Moed, Seder Nashim, and parts of Seder Nezikin, publishing articles on these topics in the journal "HaDarom." In 1972, a second volume of his book was published, compiling his studies on the remaining tractates of Seder Moed.

Most of the notes in the "Glosses of the Talmud" also appear in different forms in Rabbi Eger's other, more detailed writings, such as "Derush V’Chiddush." Therefore, it is customary to compare them to discern his precise intention in places where he was highly concise.

Margins of the Jerusalem Talmud

[edit]In 1981, a small booklet containing Rabbi Akiva Eger's "Margins of the Jerusalem Talmud" was published in London.[72] These were notes recorded on the margins of the Order of Nashim of the Jerusalem Talmud that he studied. Before this publication, "The Widow and Brothers Rom Press" conducted a feverish search in 1913 for these margins, hoping to publish them in their edition of the Jerusalem Talmud. At their request, Rabbi Dr. Avraham Yitzchak Bleicherode, a great-grandson of Rabbi Eger, reached out through the "Akiva Eger Family Association" to all of Rabbi Eger's descendants in an attempt to locate the copy of the Jerusalem Talmud he possessed. These searches proved futile.[73] In one of his responsa, Rabbi Eger quotes a passage from his Jerusalem Talmud margins on Order of Nezikin, but this volume was lost, and its fate remains unknown.

Rabbi Akiva Eger's questions

[edit]

Rabbi Akiva Eger was known for his sharp mind and his logical and insightful questions (kushiyot). His questions became famous in study halls and posed intellectual challenges for the best scholars. Rabbi Eger even categorized the severity of his questions: in his writing style, the suffix "u'tzarikh iyun" (needs analysis) indicates a severe, unresolved question, while the suffix "u'tzarikh iyun gadol" (needs extensive analysis) signifies an exceptional, extraordinary query.[74] When he adds a suffix like "and may God enlighten my eyes," the question is considered unsolvable.

Given the extensive focus on his questions, books compiling his unanswered queries have also been published. In 1982, his descendants published the book "Kushiot Atsumot" from his manuscript, containing 1,401 questions, many of which had not appeared in his previously printed works. These collections were integrated, as much as possible, into the volumes of his Talmudic teachings.

As early as 1876, just forty years after the first publication of his book "Derush V’Chiddush," Rabbi Eger's questions became widespread in study halls and served as the basis for Torah works primarily aimed at resolving these questions. Rabbi Yissachar Dov Heltercht from Lubranitz published his book "Chazot Kashot," stating:

"It is dedicated to resolving over a thousand questions raised on the Talmud by our holy Rabbi... the marvel of the generation, the pride of Israel... Akiva Eger in his work Derush and Chiddush [!] and also in his margins on the Talmud."

In 1898, Rabbi Yitzchak Tzvi Aronovsky printed his book "Yad Yitzchak" in Vilna[75]

"to settle the understanding of our Talmudic sages, Rashi, and Tosafot from all the questions and doubts that the great Gaon, the leader of the generation, Rabbi Akiva Eger, raised in the margins of the Talmud."

In 1905-1912, Rabbi Binyamin Rabinowitz published in Jerusalem his book "Mishnat Rabbi Binyamin,"[76] which

"aims to answer the questions of the holy Gaon, Rabbi Akiva Eger, of blessed memory, that appear in his notes on all Six Orders of the Mishnah."

In 1934-1937, Rabbi Moshe Avraham from Wienchter printed his book "Ganon V’Hatzil" in Brooklyn,[77] dedicated to

"defending and rescuing the words of our holy sages from the questions and doubts left unresolved by the holy Gaon, the light of the exile, Rabbi Akiva Eger, of blessed memory, in his notes on the Mishnah."[78]

In 1979, a book titled "Choshen Yeshuot" was published in Jerusalem. On the title page, the author, Rabbi Avraham Zilberman, claimed that he "answers all of the questions of Rabbi Akiva Eger of blessed memory on Orders Nashim and Nezikin."

Another ongoing attempt was made by Rabbi Shmuel Aharon Shazuri, who dedicated a regular column titled 'Asheshot' in his journal "Kol Torah"[79] systematically aimed at resolving Rabbi Eger's questions in the margins of the Talmud.

Annotations and novellae on the "Shulchan Aruch"

[edit]For years, Rabbi Akiva Eger recorded his notes on the margins of the Shulchan Aruch he studied. These notes included print corrections, comments on sources of the law, questions, debates, and practical annotations. In his later years, Rabbi Eger entrusted his volumes of the Shulchan Aruch to his eldest son, Rabbi Avraham, to prepare them for printing. Rabbi Eger deliberated whether to print his notes as a standalone book or as an appendix to the margins of the Shulchan Aruch. About a year before his death, he expressed this dilemma in a letter to his son, requesting the edited version of the notes for review before printing:

"Perhaps it is right for you to print the new insights from me next to the Shulchan Aruch... or make it a separate volume like the book Degul Meravava."[80] In either case, I do not understand your delay in sending me the booklet on Orach Chaim to review it once more... until then, it cannot go to print."

About a month later, he confirmed in a letter that the annotations were suitable for print. However, the printing of the annotations was delayed for over twenty years after Rabbi Eger's death, and they were first printed in Berlin in 1862 by his grandson Avraham Moshe Bleicherode. Concurrently, his son R. Itzik Leib printed another edition of his father's annotations on the Shulchan Aruch in Johannisburg (Pisz), Prussia. Other manuscripts of the annotations also exist. At the end of the 20th century, a comparative edition of Rabbi Eger's annotations on the Shulchan Aruch, including the various versions, was published.[81]

Rabbi Akiva Eger used to write his notes on the margins of the books in his library. As a result, besides his printed annotations on the margins of the Babylonian Talmud and the Shulchan Aruch, many books from his library, which dispersed over the years, are held by collectors and continue to be discovered and published from time to time in Torah compilations.[82] Sometimes, he had several copies of the same book in his library, and his notes were recorded randomly on different copies. Due to the high value placed on Rabbi Eger's writings in the yeshiva world, even his duplicated annotations receive printed editions, even when the book on which they were written is not a foundational work like the Shulchan Aruch.[83]

Novellae on Aggadah and Tanakh

[edit]Rabbi Akiva Eger left behind a notebook of novellae on matters of Aggadah, including insights on verses of the Tanakh. This notebook was mentioned by Rabbi Eger's sons[84] and was known until World War II.[85] Since then, as far as is known, its traces have disappeared.

Nevertheless, many of Rabbi Eger's novellae on the Tanakh have survived through citations in his other books and those of his students and colleagues. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, attempts were made to compile them, such as the collection "Midrashei U’Chiddushei Rabbi Akiva Eger on the Torah,"[86] which includes insights on other books of the Nevi'im and Ketuvim, some from unpublished manuscripts and most from collected sources.

Disciples

[edit]

- Rabbi Akiva Yisrael Wertheimer (1778–1835), chief rabbi of Altona and Schleswig-Holstein from 1823 until his death.

- Rabbi Yaakov Tzvi Mecklenburg (1785?–1865), a rabbi in Germany. Author of "HaKetav VeHaKabalah," the first complete commentary on the Torah written in opposition to the Reform approach, combining Peshat (simple meaning) with the words of Chazal (our Sages).

- Rabbi Yosef Zundel of Salant (1786–1865), founder of the Mussar Movement and teacher of Rabbi Yisrael Salanter. In his later years, he served as the posek (halakhic authority) for the Ashkenazi community in Jerusalem.

- Rabbi Aharon Fold of Frankfurt (1790–1861), author of "Beit Aharon."[87]

- Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch Kalischer (1795–1874), rabbi and thinker, author of "Drishat Tzion," considered one of the heralds of Zionism, known for his early support of the idea of Aliyah to the Land of Israel and the renewal of settlement there, promoting cooperation between the Maskilim (enlightened ones) and observant Jews.

- Rabbi Eliyahu Guttmacher (1796–1874), rabbi, Kabbalist, and thinker. Known for his followers' treatment of him as a Hasidic Rebbe in non-Hasidic Germany. Among the first advocates of agricultural settlement in the Land of Israel in the 19th century.

- Rabbi Avraham Dov Ber Flamm (1795–1876), writer and well-known preacher, editor and biographer of the books of the Maggid of Dubno.

- Rabbi Aharon Yehuda Levin Lazarus (?–1874), rabbi of the Filehne community, father of the famous philosopher and psychologist Moritz Lazarus.

- Rabbi Shlomo Plessner[88] (1797–1887), author of "Koach LaChay"[89] and many other works, including "Edut LeYisrael".[90]

- Rabbi Mordechai Michael Yafe, rabbi and halachic authority, author of "She'elot U'Teshuvot Maram Yafe" and "Beit Menachem",[91] works addressing the theoretical aspects of halachic questions.

- Rabbi Moshe Pailchenfeld, rabbi of Rogozino (Rogozin), who ordained Rabbi Marcus Jastrow in 1853.

- Rabbi Yosef Feder, dayan in Breslau, author of the books "Ometz Yosef" and "Yosef Ometz."

- Rabbi Yitzchak Ettinger, rabbi of Pleschen, author of "Dudaei Mahari"[92] on the Torah.

- His brother-in-law, Rabbi Shimon Segal Levi (son of his father-in-law Rabbi Yehoshua Feivelman), rabbi of Pardon and Rogozino (Ragazin), author of "Sha'ar Shimon"[93] on four tractates of the Babylonian Talmud.

- His nephew, Rabbi Moshe Gins-Shlesinger of Hamburg, who worked on preparing his uncle's writings for publication and is frequently mentioned in his writings and in the responsa of the Chatam Sofer.

- Rabbi Shimon Shatin Katz, rabbi of Sarospatak in Hungary (1837–1861), author of the book "Kehunat Olam",[94] known as the "Maharshek Aharon" after his famous grandfather, Rabbi Shmuel Shatin Katz, author of "Kos Yeshuot."

- Yosef Zedner (1804–1871), a German-Jewish bibliographer and librarian, resident of Berlin.

- Julius Fürst (1805–1873), a Jewish historian and lexicographer, professor of Oriental languages at the University of Leipzig, and founder of the Jewish-German journal "Der Orient."

Descendants

[edit]

Many of Rabbi Akiva Eger's descendants gained prominence within the Jewish world and beyond. Among them are:

- His grandson, Rabbi Yehuda Leib Eiger, the founder of the Lublin Hasidic dynasty, and his descendants became Rebbes of the Lublin line.

- The third Rebbe of Modzitz, Rabbi Shmuel Eliyahu Taub, author of "Imrei Esh," and his descendants became Rebbes of the Modzitz dynasty.

- The mathematician and chess player, Jakob Rosanes (German: Jakob Rosanes), the son of Rabbi Eiger's son-in-law, Rabbi Meir Aryeh Leib Hakohen Rosanes.

- Rabbi Kalman Ber, Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Israel (2024-), Chief Rabbi of Netanya (2014-2024)

- The Rebbe Rabbi Menachem Mendel Landa of Biala, the son of Rabbi Aharon Tzvi Landa of New York, from the Tchenikoff dynasty, author of the book "Shemesh U'Magen." He was a great-grandson of Rabbi Rosanes.

- Rabbi David Rappaport, rabbi and Rosh Yeshiva of "Ohel Torah" in Baranovichi between the world wars. Author of the popular yeshiva book "Mikdash David" on the Talmud. His book "Tzemach David" is dedicated to the teachings of Rabbi Akiva Eger.

- Dr. Abraham Isaac Bleicherode (1867–1954), a Talmud lecturer and great-grandson of Rabbi Eiger. One of his students was Gershom Scholem, who wrote an article in his honor when he turned eighty.

- Hermann Struck, a painter and print artist of Jewish German descent, one of the prominent Jewish artists in Imperial Germany. He was a member of the Zionist Congress, and a board member of the Jewish National Fund. His father, David Solomon Struck, was a grandson of Rabbi Abraham Eger, Rabbi Akiva Eger's eldest son. Struck also painted a portrait of Rabbi Eger. The lithograph of the portrait can be viewed in the National Library collection.

- Mordechai Ovadiahu (Gotsdinor), a writer, journalist, editor, and secretary of Chaim Nachman Bialik.

- Akiva Ettinger, an early Zionist leader and agronomist. He led the Jewish National Fund's land purchases in Ottoman Palestine and functioned as director general of the Jewish Colonization Association in South Russia, Brazil, and Argentina.

- Alberto Eiguer, a French-Argentine psychiatrist and psychoanalyst. He was the president of the French Society of Family Therapy and a professor at the Institute of Psychology of the University of Paris.

- Frederic Eger, an Israeli journalist for the Times of Israel and filmmaker.

Apart from these, many descendants of Rabbi Akiva Eger are known through his daughter, Sarah, the wife of the Hatam Sofer.

Eger Family Association

[edit]In 1913, the "Eger Family Association" was founded in Europe to unite the many descendants of the family. Around 250 individuals participated in its first conference. The association held gatherings periodically and published circulars, many of which are preserved in the Abraham Isaac Bleicherode collection at the National Library in Jerusalem. In 1990, the association published a collection titled "Eger Family Association 1913–1990." It included a bibliography of the writings of Rabbi Eger and 36 detailed family trees tracing the various branches starting from Rabbi Akiva Eger the First of Halberstadt. An updated edition was published in 1993. (For more information about the association and later meetings, see: Hannah Amit, "Akiva Eger is a Kibbutznik," Amudim, Issue 606, 1997, pp. 142–143).

In the collection, the association's statutes were published. From the section detailing the association's objectives, one can observe the cultural diversity of the family members and their commitment to maintain family ties. Among other goals: to learn about the various parts of the family and connect them in a Jewish-humanistic spirit, in the light of Rabbi Akiva Eger, to promote mutual respect. To publish a detailed bibliography of Rabbi Akiva Eger's works and those written about him. To collect stories and legends about Rabbi Eger. To organize study groups on his teachings on the anniversary of his passing, in accordance with his will.

Seforim

[edit]As Rabbi Akiva Eger's works are scattered across a wide range of publications, including books, journals, pamphlets, and even individual pages published in various venues, many have seen multiple editions and photographic reproductions.[95] Below is a survey of the primary ones:[96]

Responsa and Rulings