Albireo

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 15 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 15 min

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 (ICRS) | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Cygnus |

| Albireo Aa | |

| Right ascension | 19h 30m 43.286s[1] |

| Declination | +27° 57′ 34.84″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 3.21[2] |

| Albireo Ac | |

| Right ascension | 19h 30m 43.295s[3] |

| Declination | +27° 57′ 34.62″[3] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 5.85[2] |

| Albireo B | |

| Right ascension | 19h 30m 45.3962s[4] |

| Declination | +27° 57′ 54.989″[4] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 5.11[5] |

| Characteristics | |

| Albireo Aa | |

| Evolutionary stage | Bright giant |

| Spectral type | K2II[6] |

| B−V color index | +1.13[5] |

| V−R color index | +0.92[7] |

| Albireo Ac | |

| Spectral type | B8:p[6] |

| B−V color index | +0.09[3] |

| V−R color index | +0.09[7] |

| Albireo B | |

| Spectral type | B8Ve[8] |

| U−B color index | -0.32[5] |

| B−V color index | -0.10[5] |

| Astrometry | |

| Albireo A | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −23.54[2] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 4.915 mas/yr[9] Dec.: −11.127 mas/yr[9] |

| Parallax (π) | 8.9816 ± 0.4474 mas[9] |

| Distance | 364.8+15.6 −15.3 ly (111.9+4.8 −4.7 pc)[10] |

| Albireo Aa | |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −2.45[6] |

| Albireo Ac | |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −0.25[6] |

| Albireo B | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −18.80[11] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −1.078[12] mas/yr Dec.: −1.540[12] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 8.1896 ± 0.0781 mas[12] |

| Distance | 395.4+2.9 −3.3 ly (121.3+0.9 −1 pc)[10] |

| Position (relative to Albireo A) | |

| Component | Albireo B |

| Epoch of observation | 2006 |

| Angular distance | 35.3″ [13] |

| Position angle | 54° [13] |

| Orbit[2] | |

| Primary | Aa |

| Companion | Ac |

| Period (P) | 121.65+3.34 −2.90 yr |

| Semi-major axis (a) | 0.401+0.007 −0.006″ |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0.20+0.01 −0.02 |

| Inclination (i) | 156.15+2.90 −2.63° |

| Longitude of the node (Ω) | 84.43+5.27 −4.50° |

| Periastron epoch (T) | B2026.36 |

| Argument of periastron (ω) (secondary) | 54.72+1.88 −2.24° |

| Semi-amplitude (K1) (primary) | 2.91+0.09 −0.12 km/s |

| Details | |

| Albireo Aa | |

| Mass | 5.2[2] M☉ |

| Radius | 58.69+2.83 −3.12[14] R☉ |

| Luminosity (bolometric) | 1,259[2] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 0.93[2] cgs |

| Temperature | 4,383[2] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | −0.1[15] dex |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 8.34[2] km/s |

| Albireo Ac | |

| Mass | 2.7[2] M☉ |

| Radius | 3.0[a] R☉ |

| Luminosity (bolometric) | 79[2] L☉ |

| Temperature | 10,000[2] K |

| Albireo Ad | |

| Mass | 0.085 ± 0.007[16] M☉ |

| Albireo B | |

| Mass | 3.7 ± 0.8[17] M☉ |

| Radius | 2.59[18] R☉ |

| Luminosity (bolometric) | 230 ± 90[17] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.00 ± 0.15[17] cgs |

| Temperature | 13,200 ± 600[17] K |

| Age | 100[17] Myr |

| Other designations | |

| Albireo A: β¹ Cygni, BD+27 3410, HR 7417, HD 183912/183913, HIP 95947, SAO 87301, FK5 732, MCA 55 Aac, NSV 12105 | |

| Albireo B: β² Cygni, STF 4043B, BD+27 3411, HD 183914, HIP 95951, HR 7418, SAO 87302[22] | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | β Cyg (STF 4043) |

| Albireo A | |

| Albireo Aa | |

| Albireo Ab | |

| Albireo B | |

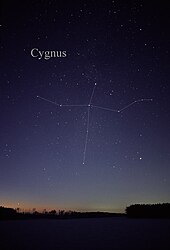

Albireo /ælˈbɪrioʊ/[23] is a binary star designated Beta Cygni (β Cygni, abbreviated Beta Cyg, β Cyg). The International Astronomical Union uses the name "Albireo" specifically for the brightest star in the system.[24] Although designated 'beta', it is fainter than Gamma Cygni, Delta Cygni, and Epsilon Cygni and is the fifth-brightest point of light in the constellation of Cygnus. Appearing to the naked eye to be a single star of magnitude 3, viewing through even a low-magnification telescope resolves it into its two components. The brighter yellow star, itself a very close trinary system, makes a striking colour contrast with its fainter blue companion.[25]

Nomenclature

[edit]

β Cygni (Latinised to Beta Cygni) is the system's Bayer designation. The brighter of the two components is designated β¹ Cygni or Beta Cygni A and the fainter β² Cygni or Beta Cygni B.

The origin of the star system's traditional name Albireo is unclear. Christian Ludwig Ideler traced it to the heading for the constellation we call Cygnus in Ptolemy's star catalog, in the translation of the Almagest by Gerard of Cremona: "Stellatio Eurisim: et est volans; et jam vocatur gallina. et dicitur eurisim quasi redolens ut lilium ab ireo" ("Constellation Eurisim: and it is the Flyer, and it is also called the Hen, and it is called Eurisim as if redolent like the lily from the 'ireo'"). (The original Greek just calls the constellation "Ορνιθος αστερισμος", "the constellation of the Bird".) The word "ireo" is obscure as well – Ideler suggests that Gerard took "Eurisim" to mean the plant Erysimum, which is called irio in Latin, but the ablative case of that is not "ireo" but irione.[26] In any case, Ideler proposed that (somehow) the phrase "ab ireo" was applied to the star at the head of the bird, and this became "Albireo" when an "l" was mistakenly inserted as though it was an Arabic name.[27] Ideler also supposed that the name Eurisim was a mistaken transliteration of the Arabic name "Urnis" for Cygnus (from the Greek "Ορνις").

In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[28] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN's first bulletin of July 2016[29] included a table of the first two batches of names approved by the WGSN; which included Albireo for β¹ Cygni. It is now so entered in the IAU Catalog of Star Names.[24]

Medieval Arabic-speaking astronomers called Beta Cygni minqār al-dajājah (English: the hen's beak).[30] The term minqār al-dajājah (منقار الدجاجة) or Menchir al Dedjadjet appeared in the catalogue of stars in the Calendarium of Al Achsasi Al Mouakket, which was translated into Latin as Rostrum Gallinae, meaning the hen's beak.[31]

Since Cygnus is the swan, and Beta Cygni is located at the head of the swan, it is sometimes called the "beak star".[32] With Deneb, Gamma Cygni (Sadr), Delta Cygni, and Epsilon Cygni (Gienah), it forms the asterism called the Northern Cross.[33]

Properties

[edit]

Beta Cygni is about 420 light-years (129 pc) away from the Sun.[2] When viewed with the naked eye, Albireo appears to be a single star. However, in a telescope it resolves into a double star consisting of β Cygni A (amber, apparent magnitude 3.1), and β Cygni B (blue-green, apparent magnitude 5.1).[34] Separated by 35 seconds of arc,[13] the two components provide one of the best contrasting double stars in the sky due to their different colors.

It is not known whether the two components β Cygni A and B are orbiting around each other in a physical binary system, or if they are merely an optical double.[2] If they are a physical binary, their orbital period is probably at least 100,000 years.[34] Some experts, however, support the optical double argument, based on observations that suggest different proper motions for the components, which implies that they are unrelated.[35] The primary and secondary also have different measured distances from the Hipparcos mission – 434 ± 20 light-years (133 ± 6 pc) for the primary and 401 ± 13 light-years (123 ± 4 pc) for the secondary.[36] More recently the Gaia mission has measured distances of about 330–390 light years (100–120 parsecs) for both components, but noise in the astrometric measurements for the stars means that data from Gaia's second data release is not yet sufficient to determine whether the stars are physically associated.[37]

In around 3.87 million years, Albireo will become the brightest star in the night sky.[38] It will peak in brightness with an apparent magnitude of –0.53 in 4.61 million years.[38]

There are a further 10 faint companions listed in the Washington Double Star catalogue, all fainter than magnitude 10. Only one is closer to the primary than Albireo B, with the others up to 142" away.[20]

Albireo A

[edit]The spectrum of Beta Cygni A was found to be composite when it was observed as part of the Henry Draper Memorial project in the late 19th century, leading to the supposition that it was itself double.[39] This was supported by observations from 1898 to 1918 which showed that it had a varying radial velocity.[40] In 1923, the two components were identified in the Henry Draper Catalogue as HD 183912 and HD 183913.[41][42]

In 1978, speckle interferometry observations using the 1.93m telescope at the Haute-Provence Observatory resolved a companion at 0.125". This observation was published in 1980,[43] and the companion is referred to as component Ab in the Washington Double Star Catalog.[20]

In 1976 speckle interferometry was used to resolve a companion using the 2.1-meter telescope at the Kitt Peak National Observatory. It was measured at a separation of 0.44", and it is noted that the observation was inconsistent with the Haute-Provence observations and hence not of the same star.[21][44] Although these observations pre-dated those at Haute-Provence, they were not published until 1982 and this component is designated Ac in the Washington Double Star Catalog.[20] It is designated as component C in the Catalog of Components of Double and Multiple Stars,[45] not to be confused with component C in the Washington Double Star Catalog which is a faint optical companion.[20] An orbit for the pair has since been computed using interferometric measurements, but as only approximately a quarter of the orbit has been observed, the orbital parameters must be regarded as preliminary. The period of this orbit is 214 years.[21] The confirmed close pair are referred to as Aa and Ac in modern papers, with Ab being the unconfirmed third component.[2] A 2022 study treats the existence of Albireo Ab as "very unlikely".[16]

In 2022, a third component was found to be orbiting Albireo Aa, named Albireo Ad. It is a very-low-mass star with around 8.5% the Sun's mass and an orbital period of 371 days.[16]

The diameter of the primary K-type giant star has been measured using interferometry from the Navy Precision Optical Interferometer. A limb-darkened angular diameter of 4.904 mas was measured. At the parallax-derived distance of 111.4 pc, a radius equivalent to 58.69 R☉ is calculated.[14]

Albireo B

[edit]β Cygni B is a fast-rotating Be star, with an equatorial rotational velocity of at least 250 kilometers per second.[25] Its surface temperature has been spectroscopically estimated to be about 13,200 K.[17]

β Cygni B has been reported to be a very close double,[46] but the observations appear to have been incorrect.[20]

Moving group

[edit]Analysis of Gaia Data Release 2 astrometry suggests that four fainter stars may form a moving group along with the brighter visible components.[2]

Namesakes

[edit]Albireo (AK-90) was a United States Navy Crater-class cargo ship named after the star.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Applying the Stefan-Boltzmann Law with a nominal solar effective temperature of 5,772 K:

References

[edit]- ^ a b Høg, E; Fabricius, C; Makarov, V. V; Urban, S; Corbin, T; Wycoff, G; Bastian, U; Schwekendiek, P; Wicenec, A (2000). "The Tycho-2 catalogue of the 2.5 million brightest stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 355: L27. Bibcode:2000A&A...355L..27H.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Drimmel, Ronald; Sozzetti, Alessandro; Schröder, Klaus-Peter; Bastian, Ulrich; Pinamonti, Matteo; Jack, Dennis; Hernández Huerta, Missael A. (2021). "A celestial matryoshka: Dynamical and spectroscopic analysis of the Albireo system". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 502 (1): 328. arXiv:2012.01277. Bibcode:2021MNRAS.502..328D. doi:10.1093/mnras/staa4038.

- ^ a b c Fabricius, C; Høg, E; Makarov, V. V; Mason, B. D; Wycoff, G. L; Urban, S. E (2002). "The Tycho double star catalogue". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 384: 180–189. Bibcode:2002A&A...384..180F. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20011822.

- ^ a b Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2021). "Gaia Early Data Release 3: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 649: A1. arXiv:2012.01533. Bibcode:2021A&A...649A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039657. S2CID 227254300. (Erratum: doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039657e). Gaia EDR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ a b c d Ducati, J. R (2002). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Photometry in Johnson's 11-color system". CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues. 2237. Bibcode:2002yCat.2237....0D.

- ^ a b c d Ginestet, N.; Carquillat, J. M. (2002). "Spectral Classification of the Hot Components of a Large Sample of Stars with Composite Spectra, and Implication for the Absolute Magnitudes of the Cool Supergiant Components". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 143 (2): 513. Bibcode:2002ApJS..143..513G. doi:10.1086/342942.

- ^ a b Ten Brummelaar, Theo; Mason, Brian D; McAlister, Harold A; Roberts, Lewis C; Turner, Nils H; Hartkopf, William I; Bagnuolo, William G (2000). "Binary Star Differential Photometry Using the Adaptive Optics System at Mount Wilson Observatory". The Astronomical Journal. 119 (5): 2403. Bibcode:2000AJ....119.2403T. doi:10.1086/301338.. See tables 4, 5, 6, and 8. Luminosity from Lbol=102(4.75−Mbol)/5.

- ^ Levenhagen, R. S; Leister, N. V (2006). "Spectroscopic analysis of southern B and Be stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 371 (1): 252–262. arXiv:astro-ph/0606149. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.371..252L. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10655.x. S2CID 16492030.

- ^ a b Vallenari, A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2023). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 674: A1. arXiv:2208.00211. Bibcode:2023A&A...674A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940. S2CID 244398875. Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ a b Bailer-Jones, C. A. L.; Rybizki, J.; Fouesneau, M.; Demleitner, M.; Andrae, R. (2021-03-01). "Estimating distances from parallaxes. V: Geometric and photogeometric distances to 1.47 billion stars in Gaia Early Data Release 3". The Astronomical Journal. 161 (3): 147. arXiv:2012.05220. Bibcode:2021AJ....161..147B. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/abd806. ISSN 0004-6256. Data about this star can be seen here.

Beta1 Cygni = Gaia DR3 2026116260337482112

Beta2 Cygni = Gaia DR3 2026113339752723456 - ^ Kharchenko, N. V; Scholz, R.-D; Piskunov, A. E; Röser, S; Schilbach, E (2007). "Astrophysical supplements to the ASCC-2.5: Ia. Radial velocities of ˜55000 stars and mean radial velocities of 516 Galactic open clusters and associations". Astronomische Nachrichten. 328 (9): 889. arXiv:0705.0878. Bibcode:2007AN....328..889K. doi:10.1002/asna.200710776. S2CID 119323941.

- ^ a b c Vallenari, A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2023). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 674: A1. arXiv:2208.00211. Bibcode:2023A&A...674A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940. S2CID 244398875. Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ a b c Entry, The Washington Double Star Catalog, identifier 19307+2758, discoverer identifier STFA 43. Accessed on line July 9, 2008. Archived 8 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Baines, Ellyn K.; Clark, James H., III; Schmitt, Henrique R.; Stone, Jordan M.; von Braun, Kaspar (2023-12-01), "33 New Stellar Angular Diameters from the NPOI, and Nearly 180 NPOI Diameters as an Ensemble", The Astronomical Journal, 166 (6): 268, Bibcode:2023AJ....166..268B, doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ad08be, ISSN 0004-6256

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lèbre, A.; De Laverny, P.; Do Nascimento, J. D.; De Medeiros, J. R. (2006). "Lithium abundances and rotational behavior for bright giant stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 450 (3): 1173. Bibcode:2006A&A...450.1173L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053485.

- ^ a b c Jack, D.; Schröder, K.-P.; Mittag, M.; Bastian, U. (2022-05-01). "Yet another star in the Albireo system - The discovery of Albireo Ad". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 661: A49. arXiv:2203.04222. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243255. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ a b c d e f Table 1, Levenhagen, R. S. (2004). "Physical Parameters of Southern B- and Be-Type Stars". The Astronomical Journal. 127 (2): 1176–1180. Bibcode:2004AJ....127.1176L. doi:10.1086/381063. S2CID 121487369.

- ^ Fracassini, Massimo; Gilardoni, Giorgio; Pasinetti, Laura E. (1973). "Apparent diameters of 172 B5V-A5V stars of the Catalogue of Geneva Observatory". Astrophysics and Space Science. 22 (1): 141–152. Bibcode:1973Ap&SS..22..141F. doi:10.1007/BF00642829. S2CID 120496963.

- ^ NAME ALBIREO -- Star in double system , database entry, SIMBAD. Accessed on line July 9, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Entry, WDS identifier 19307+2758, Sixth Catalog of Orbits of Visual Binary Stars Archived 2017-11-12 at the Wayback Machine, William I. Hartkopf & Brian D. Mason, U.S. Naval Observatory. Accessed on line July 9, 2008. (19307+2758) Archived 2011-05-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Scardia, M.; Prieur, J.-L.; Pansecchi, L.; Argyle, R.W.; Sala, M.; Basso, S.; Ghigo, M.; Koechlin, L.; Aristidi, E. (2008). "Speckle observations with PISCO in Merate: IV. Astrometric measurements of visual binaries in 2005" (PDF). Astronomische Nachrichten. 329 (1): 54–68. Bibcode:2008AN....329...54S. doi:10.1002/asna.200710834. S2CID 263306085.

- ^ HD 183914 -- Emission-line Star, database entry, SIMBAD. Accessed on line July 9, 2008.

- ^ Kunitzsch, Paul; Smart, Tim (2006). A Dictionary of Modern star Names: A Short Guide to 254 Star Names and Their Derivations (2nd rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Sky Pub. ISBN 978-1-931559-44-7.

- ^ a b "IAU Catalog of Star Names". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ a b Jim Kaler. "Albireo". Retrieved 2018-01-07.

- ^ p. 24, The names of the stars and constellations compiled from the Latin, Greek and Arabic, W. H. Higgins, Leicester: Samuel Clarke, 1882.

- ^ "LacusCurtius • Allen's Star Names — Cygnus". Allen quotes (in translation) a passage from Ideler's Untersuchungen über den Ursprung und die Bedeutung der Sternnamen (1809), page 75.

- ^ "IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)". Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1" (PDF). Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ p. 196, Star-names and Their Meanings, Richard Hinckley Allen, New York, G. E. Stechert, 1899.

- ^ Knobel, E. B. (June 1895). "Al Achsasi Al Mouakket, on a catalogue of stars in the Calendarium of Mohammad Al Achsasi Al Mouakket". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 55 (8): 429. Bibcode:1895MNRAS..55..429K. doi:10.1093/mnras/55.8.429.

- ^ p. 416, In Quest of the Universe, Theo Koupelis and Karl F. Kuhn, 5th ed., Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2007, ISBN 0-7637-4387-9.

- ^ Northern Cross Archived 2008-07-08 at the Wayback Machine, entry, The Internet Encyclopedia of Science, David Darling. Accessed on line July 24, 2008.

- ^ a b p. 46, The Monthly Sky Guide, Ian Ridpath, Wil Tirion, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-521-68435-8.

- ^ Bob King (September 21, 2016). "Will the Real Albireo Please Stand Up?". Sky and Telescope. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ Van Leeuwen, F (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600.

- ^ Bailer-Jones, C. A. L; Rybizki, J; Fouesneau, M; Mantelet, G; Andrae, R (2018). "Estimating distances from parallaxes IV: Distances to 1.33 billion stars in Gaia Data Release 2". The Astronomical Journal. 156 (2): 58. arXiv:1804.10121. Bibcode:2018AJ....156...58B. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aacb21. S2CID 119289017.

- ^ a b Tomkin, Jocelyn (April 1998). "Once and Future Celestial Kings". Sky and Telescope. 95 (4): 59–63. Bibcode:1998S&T....95d..59T. – based on computations from HIPPARCOS data. (The calculations exclude stars whose distance or proper motion is uncertain.) PDF[permanent dead link]

- ^ Maury, Antonia C.; Pickering, Edward C. (1897). "Spectra of bright stars photographed with the 11-inch Draper Telescope as part of the Henry Draper Memorial". Annals of Harvard College Observatory. 28: 1. Bibcode:1897AnHar..28....1M.

- ^ Campbell, W. W. (1919). "The Variable Velocity of β Cygni". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 31 (179): 38. Bibcode:1919PASP...31...38C. doi:10.1086/122807.

- ^ "freestarcharts.com". Retrieved 2017-06-11.

- ^ Cannon, Annie Jump; Pickering, Edward Charles (1923). "The Henry Draper catalogue : 19h and 20h". Annals of the Astronomical Observatory of Harvard College. 98: 1. Bibcode:1923AnHar..98....1C.. See note re HD 183912,3,4 on this page.

- ^ Bonneau, D.; Foy, R. (1980). "Speckle interferometric observations of binary systems with the Haute-Provence 1.93 M telescope". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 86: 295. Bibcode:1980A&A....86..295B.

- ^ McAlister, H. A.; Hendry, E. M. (1982). "Speckle interferometric measurements of binary stars. VI". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 48: 273. Bibcode:1982ApJS...48..273M. doi:10.1086/190778.

- ^ Dommanget, J.; Nys, O. (1994). "Catalogue des composantes d'etoiles doubles et multiples (CCDM) premiere edition - Catalogue of the components of double and multiple stars (CCDM) first edition". Com. De l'Observ. Royal de Belgique. 115: 1. Bibcode:1994CoORB.115....1D.

- ^ Roberts, Lewis C.; Turner, Nils H.; Ten Brummelaar, Theo A. (2007). "Adaptive Optics Photometry and Astrometry of Binary Stars. II. A Multiplicity Survey of B Stars" (PDF). The Astronomical Journal. 133 (2): 545. Bibcode:2007AJ....133..545R. doi:10.1086/510335. S2CID 10416471.

Further reading

[edit]- Webb, T. W.; McAlister, H. A.; Worley, C. E.; Burnham, S. W.; Aitken, R. G. (1980). "Albireo as a Triple Star". Sky and Telescope. 59: 210. Bibcode:1980S&T....59..210W.

External links

[edit]- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Albireo: A Bright and Beautiful Double (30 August 2005)

- A picture of Albireo by Stefan Seip (Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine)

- Albireo at Pete Roberts' Fuzzy Blobs site

- About Cygnus, including more information about the origin of the name Albireo.

KSF

KSF