Amateur radio licensing in the United States

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 22 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 22 min

In the United States, amateur radio licensing is governed by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Licenses to operate amateur stations for personal use are granted to individuals of any age once they demonstrate an understanding of both pertinent FCC regulations and knowledge of radio station operation and safety considerations. There is no minimum age for licensing; applicants as young as five years old have passed examinations and were granted licenses.[1][2]

Operator licenses are divided into different classes, each of which corresponds to an increasing degree of knowledge and corresponding privileges. Over the years, the details of the classes have changed significantly, leading to the current system of three open classes and three grandfathered (but closed to new applicants) classes.

Current license classes

[edit]Amateur radio licenses in the United States are issued and renewed by the Federal Communications Commission. In 2022 the FCC began charging a Congressionally-mandated $35 administrative fee. Private individuals recognized through a Volunteer Examiner Coordinator (VEC) who administer the examinations may recoup their expenses by charging a fee in addition to the FCC's fee. Licenses currently remain valid for ten years from the date of issuance or renewal.

- The entry-level license, known as Technician Class, is awarded after an applicant successfully completes a 35-question multiple choice written examination. The license grants full operating privileges on all amateur bands above 30 MHz and limited privileges in portions of the high frequency (HF) bands.

- The middle level, known as General Class, requires passage of the Technician test, as well as a 35-question multiple-choice General exam. General class licensees are granted privileges on portions of all amateur bands, and have access to over 83% of all amateur HF bands. However, some band segments often used for long distance contacts are not included.

- The top US license class is Amateur Extra Class. This license requires the same tests as General plus a 50-question multiple choice theory exam. Those with Amateur Extra licenses are granted all privileges on all US amateur bands.

Each licensing class has its own set of possible exam questions called a question pool.[3] The pools contain a few hundred questions each, divided into several sections. Each question in a section asks about radio or electronic theory, regulations, safety topics, or the meaning of diagrams or schematics. They are multiple choice, containing three wrong answers and one correct answer. To form an exam, a requisite number of questions are taken from each section of the question pool for which one is seeking a particular class, in random order, and with the four answers in random order. The passing percentage is 74, meaning one may miss up to 9 questions on each of the Technician or General exams, or up to 13 on the Amateur Extra exam. At many exam sessions, Volunteer Examiners may offer exams for all three license classes, so if someone desired, they could be eligible to be granted an Amateur Extra license in a single day, after answering 120 questions (and passing each class). Because of this nature of these published question and answer pools, it is also possible for an applicant not to know or understand radio, electronics, safety, etc., and just rote memorize the questions and the correct answers.

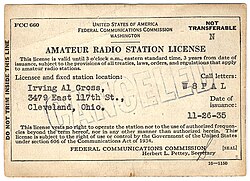

From February 17, 2015 onwards, the FCC stopped routinely sending paper copies of licenses to licensees[4] (the official license being the FCC's electronic record). However, until December 2020, it would continue sending paper copies upon a licensee's request or a licensee could print it out online from the FCC's database. As of December 2020, the FCC no longer offers paper licenses for any amateur radio licensee,[5] though users can still easily print paper copies and wallet cards from their online certifications.

Grandfathered license classes

[edit]The FCC classifications of licensing have evolved considerably since the program's inception (see History of US amateur licensing, below). When the FCC made the most recent changes it allowed certain existing operator classes to remain under a grandfather clause. These licenses would no longer be issued to new applicants, but existing licenses may be modified or renewed indefinitely.

- The Novice Class operator license was for persons who had passed a 5 word per minute (wpm) Morse code examination and a basic theory exam.[6] After the 1987 restructuring, privileges included four bands in the HF range (3–30 MHz), one band in the VHF range (30–300 MHz), and one band in the UHF range (300–3,000 MHz). This class was deprecated by the restructuring in 2000. Novice operators gained Morse code only privileges in the entire Morse code and data only segments of the General class portions of 80, 40, 15 and data and Morse code in the general section of 10 meters in 2007 just prior to the end of the Morse code requirement.

- The Advanced Class operator license, whose privileges closely match those of the General class license but included 275 kHz of additional spectrum in the HF bands, was deprecated by the restructuring in 2000.

- The Technician Plus Class was effectively introduced – though without a name – in 1990, when the requirement for Morse Code was dropped from the Technician Class. To comply with International Telecommunication Union regulations requiring Morse proficiency for working HF, Technicians were restricted to operating above 50MHz, but could gain access to the so-called Novice Class privileges (effectively getting what the Technician Class had before the change) by passing any of the contemporary Morse tests. In 1994, this was specifically separated out as a separate class, called Technician Plus. This class was deprecated by the restructuring in 2000.

Volunteer examiners

[edit]Any individual, except for a representative of a foreign government, regardless of citizenship who wishes to apply for a US amateur radio license must appear before Volunteer Examiners (VEs); any person who qualifies by examination is eligible to apply for an operator/primary station license grant. [7] VEs are licensed radio amateurs who conduct examination sessions, frequently through permanently established teams on a monthly or quarterly basis. VEs are governed by Volunteer Examiner Coordinators (VECs), organizations that "coordinate the efforts of Volunteer Examiners ... in preparing and administering amateur service operator license examinations." As of April 2021, the FCC recognizes 14 VECs.[8] The two largest VEC organizations are W5YI-VEC, a privately held company, and one sponsored by the non-profit American Radio Relay League (ARRL)[citation needed][according to whom?]. The ARRL VEC coordinates about two-thirds of all U.S. license examinations.[citation needed]

Prior to 1984, many Novice exams were administered by volunteers, but all other exams were taken at FCC offices. Some of the exam times were not always convenient for candidates, so a few exceptions were allowed in cases where candidates were physically unable to get to the field offices (such as the Conditional license, discussed elsewhere in this article).

In the 1950s and 1960s, Novice, Technician and Conditional exams were given by licensees acting as volunteer examiners[citation needed]. No Advanced and very few Amateur Extra exams were administered during this period, leaving the General exam as the only exam class regularly administered by the FCC.[citation needed]

The government's use of licensed amateur radio operators as voluntary examiners dates back to the founding of the Amateur Radio Service as a government-regulated entity in 1912 (Amateur Second Class licenses).

History of U.S. amateur licensing

[edit]Formation and early history

[edit]Established in 1912, regulation of radio was a result of the U.S. Navy's concern about interference to its stations and its desire to be able to order radio stations off the air in the event of war.[9] U.S. radio broadcasting was first governed by the U.S. Department of Commerce (the U.S. Department of Commerce and Labor until March 1913), then by the Federal Radio Commission, and finally (in 1934) by the FCC. The federal government's licensing of amateur radio experimenters and operators has evolved considerably over the century since the inception of licensing.

1912 through 1950

[edit]

Under authority of the Radio Act of 1912, the Department of Commerce issued Amateur First Grade and Amateur Second Grade operator licenses beginning in December of that year.[10] Amateur First Grade required an essay-type examination and five (later ten) words per minute code examination before a Radio Inspector at one of the Department's field offices. This class of license was renamed Amateur Class in 1927 and then Amateur First Class in 1932. Amateur Radio licensing in the United States began in mid-December 1912.

At first, the Amateur Second Grade license required the applicant to certify that he or she was unable to appear at a field office but was nevertheless qualified to operate a station. Later, the applicant took brief written and code exams before a nearby existing licensee. This class of license was renamed Temporary Amateur in 1927.

The Department of Commerce created a new top-level license in 1923, the Amateur Extra First Grade, that conveyed extra operating privileges. It required a more difficult written examination and a code test at twenty words per minute. In 1929, a special license endorsement for "unlimited radiotelephone privileges" became available in return for passing an examination on radiotelephone subjects. This allowed amateurs to upgrade and use reserved radiotelephone bands without having to pass a difficult code examination.

From 1912 through 1932, amateur radio operator licenses consisted of large and ornate diploma-form certificates. Amateur station licenses were separately issued on plainer forms.

In 1933, the Federal Radio Commission (FRC) reorganized amateur operator licenses into Classes A, B and C.

- Class A conveyed all amateur operating privileges, including certain reserved radiotelephone bands. Amateur Extra First Grade licensees and Amateur First Class licensees with "unlimited radiotelephone" endorsements were grandfathered into this class.

- Class B licensees did not have the right to operate on the reserved radiotelephone bands. Amateur First Class licensees were grandfathered into this class.

- Class C licensees had the same privileges as Class B licensees, but took their examinations from other licensees rather than from Commission field offices. Because examination requirements were somewhat stiffened, Temporary Amateur licensees were not grandfathered into this class but had to be licensed anew.

In addition, that year the FRC began issuing combined operator and station licenses in wallet-sized card form.

During the First World War, licensing was suspended and amateurs were ordered to render their equipment inoperable. The military attempted to preserve this situation after armistice, though amateurs resisted and prevailed. During the Second World War, station licenses were again suspended, though operator licenses continued to be issued and renewed, which did allow hams to listen if not transmit, and rights were phased back in following the war's end.[11]

1951 license restructuring

[edit]In 1951, the FCC moved to convert the existing three license classes (A, B, and C) into named classes, and added three new license classes.

Novice was a new 1-year non-renewable introductory license with very limited privileges. It required passing 5 wpm code (sending and receiving) and a simple written test.

Technician was a new 5-year license meant for experimenters. Full privileges on 220 MHz and higher, no privileges below 220 MHz. 5 wpm code tests and the same written test as Conditional and General.

General was the renamed Class B. 5-year license, full privileges except no phone privileges on the bands between 2.5 and 25 MHz (temporary restriction - see below). 13 wpm code and the same written test as Conditional and Technician. FCC exam only.

Conditional was the renamed Class C. 5-year license, full privileges except no phone privileges on the bands between 2.5 and 25 MHz (temporary restriction - see below). 13 wpm code and the same written test as General and Technician. Exam by mail.

Advanced was the renamed Class A. 5-year license, full privileges. Advanced required holding a General or Conditional for at least 1 year, plus an added written test. If the prospective Advanced had a Conditional, s/he had to pass 13 wpm code and the same written test as General and Technician at an FCC exam session before being allowed to try for Advanced. FCC exam only.

Amateur Extra was a new 5-year license, full privileges. Required holding an Advanced, General or Conditional for at least 2 years, plus 20 wpm code and an added written test. If the prospective Extra had a Conditional, s/he had to pass 13 wpm code and the same written test as General and Technician at an FCC exam session before being allowed to try for Extra. FCC exam only.

The new Amateur Extra was intended to replace the Advanced as the top license. No new Advanced licenses would be issued after December 31, 1952.

Note that the Advanced class license was made available again for new issues on November 22, 1967 with the incentive licensing program. Advanced class was still attainable in the interim by those migrating from Class A. [12]

The 1951 restructuring meant that anyone who wanted HF 'phone on the bands between 2.5 and 25 MHz would have to get an Extra if they didn't get an Advanced before the end of 1952. This caused a number of amateurs to get Advanced licenses before they became unavailable at the end of 1952.

However, near the end of 1952, FCC reversed its policy and gave full privileges to Generals and Conditionals, effective mid-Feb 1953. For the next 15+1⁄2 years, there were 6 license classes in the US (Novice, Technician, General, Conditional, Advanced and Amateur Extra) and four of those classes had full privileges. Only Novices and Technicians did not have full privileges.

Over time, the privileges of the various licenses classes changed. Technicians got 6 meters and later part of 2 meters in the 1950s. Novice privileges were expanded in the 1950s, with the addition of parts of 40 and 15 meters added and 11-meter privileges removed.

Incentive licensing

[edit]In 1964, the FCC and the American Radio Relay League (ARRL) developed a program known as "Incentive Licensing," which rearranged the HF spectrum privileges. The General/Conditional and Advanced portions of the HF bands were reduced, with the spectrum reassigned to those in the Advanced and Amateur Extra classes. It was hoped that these special portions of the radio spectrum would provide an incentive for hams to increase their knowledge and skills, creating a larger pool of experts to lead the Space Age.[citation needed] It did not take effect until 1968.

The Advanced class license was made available again for new issues, by exam, on November 22, 1967 with the incentive licensing program. [12]

Prior to the advent of incentive licensing, only a small percentage of General Class operators progressed to the Amateur Extra Class. After incentive licensing, a large number of amateurs attained Advanced and Amateur Extra Class licenses. Thus, incentive licensing was successful in inducing a large number of amateurs to study and upgrade their knowledge and license privileges. Incentive licensing was not without controversy; a number of General class operators, unhappy at having their privileges reduced, dropped out of the hobby rather than upgrade.[citation needed] One of the first foreign born non-citizen Ham radio operator was Julio Ricardo Ahumada LU7BD - from Argentina. Up until 1968 it was illegal for a non-citizen to operate a ham radio.

Novice enhancement

[edit]Prior to 1987, the only difference between the requirements for Technician and General licenses was the Morse telegraphy test, which was five words per minute (wpm) for Technician and 13 wpm for General. The written test, then called element 3, was the same for both classes.

In 1987, a number of changes, later called the "Novice Enhancement," were introduced. Among them, element 3 was split into two new exams, element 3A, which covered VHF theory and 3B, which covered HF theory. Element 3A became a requirement for the Technician class and element 3B became a requirement for General. Both classes also required candidates to have passed the Novice element 2 theory exam.[13]

The changes also granted Novice and Technician classes limited voice privileges on the 10-meter HF band. Novices were also granted voice privileges on portions of the then-220-MHz (since changed to 222 MHz) and 1,240 MHz bands using limited power. For the first time, Novices and Technicians were able to operate using single sideband voice and data modes on HF. It was hoped that this would prompt more hams to move up to General, once they had a chance to sample HF without a Morse key.[citation needed]

Technician: the first license without Morse code

[edit]In late 1990, the FCC released their Report and Order on Docket 90-55. Beginning on February 14, 1991, demonstration of proficiency in Morse code telegraphy was removed from the Technician license requirements.[14][15] Because International Telecommunication Union (ITU) regulations still required proficiency in Morse telegraphy for operation below 30 MHz, new Technicians were allowed all modes and bands above 30 MHz. If a Technician passed any of the contemporary Morse tests, he or she gained access to the so-called Novice HF privileges, essentially "upgrading" to what a Tech had before the new rules went into effect. This new, sixth class had no name until the FCC started calling them "Technician Plus" in 1994.[16] With a code-free class now available, Technician class became a second entry class, eventually surpassing the number of Novice class license holders.[17][18]

Restructuring in 2000 and CORES registration numbers

[edit]In 1999, the FCC moved to simplify the Amateur Radio Service operator license structure, streamline the number of examination elements, and reduce the emphasis on telegraphy. The change was titled a restructuring, and the new rules became effective on April 15, 2000.[19]

The major changes were:

- A reduction of the number of operator license classes from six to the current three (Technician, General, Extra). The Advanced Class, Technician Plus Class, and Novice Class licenses were deemed redundant and would no longer be issued; however, existing licensees would retain their operating privileges and be allowed to renew their licenses.

- A reduction of the number of telegraphy examination element levels from three to one. Both the Amateur Extra Class' 20 words-per-minute (WPM); and General and Advanced classes' 13 WPM Morse code tests, were removed in favor of a standardized 5 WPM as the sole Morse code requirement for both the General and Extra Class licenses. With the removal of the high-speed Morse code tests, physician certification waivers were no longer accepted.

- A reduction of the number of written examination elements from five to three.

- Authorization of Advanced Class amateur radio operators to prepare and administer examinations for the General Class license.

- Elimination of station licenses for the Radio Amateur Civil Emergency Service (RACES).

In addition to the above changes, the FCC instituted an additional system of identification for all licensees (even beyond amateur radio itself) in the United States, named the "CORES" (COmmission REgistration System"), which added a ten-digit "FRN" ("FCC Registration Number") to all licensees' paper licenses, generally in the same Y2K-timeframe.[20]

With the rule simplification, all pre-1987 Technician operators were now qualified to become General class operators, having already passed both the theory and code exams now required for the higher class. All that was necessary was to apply for the General license, usually through a "paper upgrade" (often done through existing amateur radio clubs) to achieve the license acquisition. The restructuring also enabled a pre-1987 Technician operator to become an Extra operator simply by passing the element 4 theory examination. Additionally, an expired or unexpired Novice class license could be used as credit toward the 5 WPM Morse code examination when upgrading.[21]

With the change, Technicians who could pass the 5 WPM Morse code examination were given the same HF-band privileges as the Technician Plus class, although the FCC's callsign database no longer distinguished between those Technician licensees possessing HF privileges and those who did not.

End of Morse code requirement

[edit]In 2003, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) ratified changes to the Radio Regulations to allow each country to determine whether it would require a person seeking an amateur radio operator license to demonstrate the ability to send and receive Morse code. The effect of this revision was to eliminate the international requirement that a person demonstrate Morse code proficiency in order to qualify for an amateur radio operator license with transmitting privileges on frequencies below 30 MHz.[22]

With this change of international rules, the FCC announced on December 15, 2006 that it intended to adopt rule changes which would eliminate the Morse code requirement for amateur operator licenses.[22][23] Shortly thereafter, the effective date of the new rules was announced as February 23, 2007. After that date, the FCC immediately granted the former Technician Plus privileges to all Technician Class operators, consolidating the class into a single set of rules.

Following the change in requirements, the ARRL reported a significant increase in the number of applications for licensing.[24]

Call signs

[edit]Each station is assigned a call sign which is used to identify the station during transmissions.

Amateur station call signs in the US take the format of one or two letters (the prefix), then a numeral (the call district), and finally between one and three letters (the suffix). The number of letters used in the call sign is determined by the operator's license class and the availability of letter combinations.

The format of the callsign is often abbreviated as X-by-Y where a number in place of the X or Y indicates the quantity of letters, separated by a single digit of the call district. For example, W2PE would be a 1 by 2. X is only 1 or 2, and Y is 1, 2, or 3.

Currently there are 13 geographically based regions. There were 9 original call districts within the 48 contiguous states, also known as radio inspection districts. [3] [4] [5] The 10th district (with numeral Ø) was split from the 9th district. Three additional regions cover Alaska, the Caribbean (including Puerto Rico), and the Pacific (including Hawaii).

In the last few decades the FCC has discarded the requirement that a station be located in the corresponding numerical district. Whereas at one time the callsign W1xxx would have been solid identification that the station was in New England (district 1), that is no longer the case, and W1xxx may be located anywhere in the USA. Even particularly distinctive calls such as KH6xxx which used to be exclusively in Hawaii, may be assigned to license holders on the US mainland. However, those licensees with KH6, KL7, KP4, etc., call signs must have been living (or had a mailing address) in Hawaii, Alaska or Puerto Rico when they received those call signs.

A newly licensed amateur will always receive a call sign from the district in which they live. For instance, a newly licensed Technician from New England would receive a call sign of the form KC1xxx. The amateur may thereafter apply for a specific or specialized call sign under the Vanity Licensing program.

Approximately 88% of all amateur radio operators have call signs that reflect the district in which those operators live.[25]

An amateur operator with an Amateur Extra Class license can hold a call from any of the four call sign groups, either by keeping an existing call sign (indefinitely, since there is no requirement to change call sign upon license renewal), or by choosing a Group B, C or D call sign under the Vanity Licensing Program.

Likewise, Advanced Class licensees can hold Group C or D call signs, as well as Group B, and any operator may choose a Group D call sign (in reality, all new licensees, except Amateur Extra, are assigned Group D call signs, since the supply of available Group C "1x3" call signs was quickly depleted with the elimination of the Element 1A Morse Code requirement for the Technician Class in 1991)

| Class | Size | Format | Letters | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Amateur Extra Class | Four characters | 1-by-2 | K, N, or W plus two letters | W1AW |

| 2-by-1 | AA–AK, KA–KZ, NA–NZ, or WA–WZ plus one letter | ABØC | |||

| Five characters | 2-by-2 | AA–AK plus two letters | ADØEC | ||

| Group B | Advanced Class[26] | Five characters | 2-by-2 | KA–KZ, NA–NZ, or WA–WZ plus two letters | NZ9WA |

| Group C | Technician or General Classes | Five or six characters | 1-by-3 | K, N, or W plus three letters | N1NJA |

| 2-by-3 (location specific) |

KL, NL, or WL; NP or WP; KH, NH, or WH, plus three letters | KL5CDE | |||

| Group D | Novice,[26] Club, and Military Recreation Stations; and sequentially to Technician or General | Six characters | 2-by-3 (Novice or Club) |

KA–KZ, WA–WZ plus three letters | KA2DOG |

| 2-by-3 (Sequential) |

KA–KZ plus three letters | KNØWCW | |||

| Source: FCC Callsign information | |||||

The call district assignments are as follows (note that a station may not actually be located in the district indicated by the numeral in the stations's callsign) :[27]

| District | Numeral | States and Territories | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | ME, NH, MA, RI, CT, VT | |

| 2 | 2 | NY, NJ | |

| 3 | 3 | PA, DE, MD, DC | |

| 4 | 4 | KY, VA, TN, NC, AL, GA, SC, FL | |

| 5 | 5 | NM, TX, OK, AR, LA, MS | |

| 6 | 6 | CA | |

| 7 | 7 | WA, OR, ID, MT, WY, NV, UT, AZ | |

| 8 | 8 | MI, OH, WV | |

| 9 | 9 | WI, IL, IN | |

| 10 | 0 | ND, SD, NE, KS, CO, MN, IA, MO | |

| 11 | L0–L9 | AK | |

| 12 | P1–P5 | Caribbean | |

| P1: Navassa Island | P3/P4: Puerto Rico | ||

| P2: U.S. Virgin Islands | P5: Desecheo Island | ||

| 13 | H0–H9 | Hawaii and Pacific | H5K: Kingman Reef |

| H1: Baker, Howland Islands | H6/7: Hawaii | ||

| H2: Guam | H7K: Kure Island | ||

| H3: Johnston Atoll | H8: American Samoa | ||

| H4: Midway Island | H9: Wake Island | ||

| H5: Palmyra Atoll, Jarvis Island | H0: Northern Marianas | ||

Because the FCC will not issue long-term licenses to locations without mailing addresses, operators visiting some of these smaller islands, such as Navassa and Wake, can apply for temporary 1x1 call signs, as discussed below. Unofficial self-identification (for example, adding a /KP5 after one's call sign for Desecheo Island) is also allowed.[28]

Sequentially assigned call signs

[edit]During the processing of a new license application, a call sign is selected from the available list sequentially using the sequential call sign system. This system is based on the alphabetized regional-group list for the licensee's operator class and mailing address.

As of December 2015, the sequential system for Group C assigns 2-by-3 formats. Call signs begin with the letter K in Regions 1 through 10 (continental United States), and with a W (along with an area specific 2nd letter and area-specific numeral) in Regions 11 through 13 (Alaska, the Caribbean, Hawaii and insular Pacific areas).[29]

Vanity callsigns

[edit]The FCC offers amateur licensees the opportunity to request a specific call sign for a primary station and for a club station.

Special event 1x1 call signs

[edit]The FCC allows the use of special event "1x1" call signs to denote special occasions such as a club's anniversary, a historic event or even a DXpedition. As an example, the call sign "N8S" was used for the April 2007 DXpedition to Swains Island in American Samoa. These call signs start with the letters K, N or W, followed by a single numeral from 0 to 9 then followed by a single letter from A through W, Y or Z. The letter X is not allowed as it is reserved for experimental stations. Thus, there are 750 such call signs available.[30] Each call sign may be used for 15 days from its issue. Each station using the special 1x1 call must transmit its assigned call at least once every hour.

Five coordinators (ARRL, W5YI Group Inc, Western Carolina Amateur Radio Society/VEC Inc, W4VEC Volunteer Examiners Club of America and the Laurel Amateur Radio Club Inc) are authorized to handle these call sign requests.[31]

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ 5-year-old passes ham radio exam

- ^ Girl Hams It Up for the World: Ham radio: At 5, she's maybe the youngest operator in U.S. Her mental skills are surprising. [1]

- ^ ARRL page listing the current question pools

- ^ "FCC "Paperless" Amateur Radio License Policy Goes into Effect on February 17". Archived from the original on 2015-02-18. Retrieved 2015-02-18.

- ^ "Obtain License Copy". www.arrl.org. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

- ^ Thomas, Ronald (2006-06-28). "The Novice License Helped Shape the '50s Ham Generation". American Radio Relay League. Archived from the original on 2007-01-26. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ^ "47 CFR 97.5 - Station license required". Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School. 2010-12-15. Archived from the original on 2017-02-19. Retrieved 2017-02-18.

- ^ "Volunteer Examiner Coordinators (VECs)". Federal Communications Commission. 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ See FCC Docket 99-412, page 3

- ^ Friedman, Neil D., N3DF, "83 Years of U.S. Amateur Licensing," The AWA Review, Vol. 9 (1995)

- ^ "The Storied History of the Ham Radio Call Sign". Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ^ a b "A History of Amateur Radio License Changes – Eastern Massachusetts ARRL".

- ^ "Impact of new rules on Novice and Technician". The W5YI Group, Inc. 2007-01-07. Archived from the original on 2007-10-07. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ^ FCC Report and Order #90-55, Codeless Technician Decision

- ^ Dinkins, Rodney R. "Amateur Radio History". Archived from the original on 27 April 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ^ FCC Order, 9 FCC Rcd 6111 (1994)

- ^ "Trends in Amateur Radio licensing over the last ten years". The W5YI Group, Inc. 2007-03-19. Archived from the original on 2007-10-07. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ^ "FCC Report and order, 99-412 page 12" (PDF). Federal Communications Commission. 1999. pp. 12 of 70. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-08-05. Retrieved 2011-06-18.

- ^ FCC's Report and Order #99-412 Archived 2011-08-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "FCC document dated July 19, 2000 announcing the then-"new" CORES registration number system". Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Lindquist, E. (2000-02-11). "FCC gives morse element credit to expired novices". American Radio Relay League, Inc. Archived from the original on 2007-02-18. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ^ a b FCC Report and Order #06-178 Archived 2011-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ FCC press release, FCC MODIFIES AMATEUR RADIO SERVICE RULES, ELIMINATING MORSE CODE EXAM REQUIREMENTS AND ADDRESSING ARRL PETITION FOR RECONSIDERATION Archived 2006-12-29 at the Wayback Machine December 15, 2006

- ^ Application Avalanche Under Way as New Codeless Testing Regime Ramps Up Archived 2007-08-27 at the Wayback Machine. ARRLWeb Bulletin. February 28, 2007

- ^ [2] Archived 2011-12-05 at the Wayback Machine N4MC's Vanity HQ, retrieved 18-Dec-2011

- ^ a b Note: vanity only; not used for new licensees

- ^ "FCC: Wireless Services: Amateur Radio Service: Call Sign Systems: Sequential". Archived from the original on 2007-02-18. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- ^ "Vanity Call Signs Request Types: By List". Archived from the original on 2015-04-14. Retrieved 2015-04-01.

- ^ "Hamdata FCC Information". Archived from the original on 2016-03-21. Retrieved 2015-12-25.

- ^ "FCC: Wireless Services: Amateur Radio Service: Call Sign Systems: Special Event". Archived from the original on 2007-05-12. Retrieved 2007-04-25.

- ^ "Special Event (1x1) Call Signs". Archived from the original on 2014-08-20. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- AC6V's History of Amateur Radio

External links

[edit]- ARRL's U.S. License Privileges by Band charts.

- FCC Information on Amateur Radio Service Operator Licensing

- FCC Information on Volunteer Examiner Coordinators

- National Conference of Volunteer Examiner Coordinators (source of question pools)

KSF

KSF