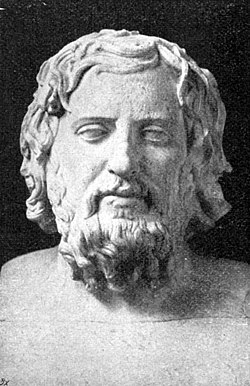

Anabasis (Xenophon)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 17 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 17 min

Anabasis (/əˈnæbəsɪs/ ə-NAB-ə-sis; Ancient Greek: Ἀνάβασις [anábasis]; lit. 'An Ascent') is the most famous work of the Ancient Greek professional soldier and writer Xenophon.[2] It gives an account of the expedition of the Ten Thousand, an army of Greek mercenaries hired by Cyrus the Younger to help him seize the throne of Persia from his brother, Artaxerxes II, in 401 BC.

The seven books making up the Anabasis were composed c. 370 BC. Although as an Ancient Greek vocabulary word (ᾰ̓νᾰ́βᾰσῐς) meaning 'embarkation', 'ascent' or 'mounting up', the title Anabasis has been rendered by some translators as The March Up Country or as The March of the Ten Thousand. The story of the army's journey across Asia Minor and Mesopotamia is Xenophon's best known work and "one of the great adventures in human history".[3]

Authorship

[edit]

Xenophon, in his Hellenica, did not cover the retreat of Cyrus but instead referred the reader to the Anabasis by "Themistogenes of Syracuse"[4]—the tenth-century Suda also describes Anabasis as being the work of Themistogenes, "preserved among the works of Xenophon", in the entry Θεμιστογένεης. (Θεμιστογένης, Συρακούσιος, ἱστορικός. Κύρου ἀνάβασιν, ἥτις ἐν τοῖς Ξενοφῶντος φέρεται: καὶ ἄλλα τινὰ περὶ τῆς ἑαυτοῦ πατρίδος. J.S. Watson in his Remarks on the Authorship of Anabasis refers to the various interpretations of the word "φέρεται", which give rise to different interpretations and different problems.[5]) Aside from these two references, there is no authority for there being a contemporary Anabasis written by "Themistogenes of Syracuse" and no mention of such a person in any other context.[citation needed]

By the end of the 1st century, Plutarch had said, in his Glory of the Athenians, that Xenophon had attributed Anabasis to a third party to distance himself as a subject from himself as a writer. While the attribution to Themistogenes has been raised many times, the view of most scholars aligns substantially with that of Plutarch and certainly that all the volumes were written by Xenophon himself.[citation needed]

Content

[edit]

Xenophon accompanied the Ten Thousand (words that Xenophon does not use), a large army of Greek mercenaries hired by Cyrus the Younger, who intended to seize the throne of Persia from his brother, Artaxerxes II. Although Cyrus' mixed army fought to a tactical victory at Cunaxa in Babylon (401 BC), Cyrus was killed, rendering the actions of the Greeks irrelevant and the expedition a failure.

Stranded deep in Persia, the Spartan general Clearchus and the other Greek senior officers were then killed or captured by treachery on the part of the Persian satrap Tissaphernes. Xenophon, one of three remaining leaders elected by the soldiers, played an instrumental role in encouraging the 10,000 to march north across foodless deserts and snow-filled mountain passes, towards the Black Sea and the comparative security of its Greek coastal cities. Abandoned in northern Mesopotamia, without supplies other than what they could obtain by force or diplomacy, the 10,000 had to fight their way northwards through Corduene and Armenia, making ad hoc decisions about their leaders, tactics, food supplies, and destiny, while the King's army and hostile natives barred their way and attacked their flanks.[citation needed]

Ultimately this "marching republic" managed to reach the Black Sea at Trabzon (Trebizond), a destination they greeted with their famous cry of exultation on the mountain of Theches (now Madur) in Hyssos (now Sürmene): "Thalatta! Thalatta!", "The sea, the sea!".[6] "The sea" meant that they were at last among Greek cities but it was not the end of their journey, which included a period fighting for Seuthes II of Thrace and ended with their recruitment into the army of the Spartan general Thibron. Xenophon related this story in Anabasis in a simple and direct manner.[citation needed]

The Greek term anabasis referred to an expedition from a coastline into the interior of a country. While the journey of Cyrus is an anabasis from Ionia on the eastern coast of the Aegean Sea, to the interior of Asia Minor and Mesopotamia, most of Xenophon's narrative is taken up with the return march of Xenophon and the Ten Thousand, from the interior of Babylon to the coast of the Black Sea. Socrates makes a cameo appearance, when Xenophon asks whether he ought to accompany the expedition. The short episode demonstrates the reverence of Socrates for the Oracle of Delphi.[citation needed]

Xenophon's account of the exploit resounded through Greece, where, two generations later, some surmise, it may have inspired Philip of Macedon to believe that a lean and disciplined Hellene army might be relied upon to defeat a Persian army many times its size.[7] Besides military history, the Anabasis has found use as a tool for the teaching of classical philosophy; the principles of statesmanship and politics exhibited by the army can be seen as exemplifying Socratic philosophy.[citation needed]

Chapter summaries

[edit]Book I

[edit]

- Cyrus makes preparations to take the throne from his brother.

- Cyrus marches to take out the Pisidians and gains troops as he progresses through the provinces.

- Word spreads that Cyrus might be moving against the king and the soldiers begin to question continuing onward.

- Cyrus and his generals continue marching onward, now towards Babylon. Xenias and Pasion are seen as cowards for deserting Cyrus.

- The soldiers face hardship with few provisions other than meat. Dissension arises after Clearchus has one of Menos's men flogged, which leads to escalating retaliation.

- Orontas is put on trial for a treasonous plot against Cyrus.

- Cyrus sizes up the situation for the coming battle against the king. Cyrus and his army pass safely through a trench constructed by the king.

- The battle between Artaxerxes's royal army and Cyrus's army commences.

- Xenophon describes a sort of eulogy after the death of Cyrus.

- The king rallies his forces and attacks Cyrus's army again. Then Artaxerxes retreats to a mound where upon being confronted again by the Hellenes, he and his men retreat for the day.

Book II

[edit]- The army finds out about Cyrus's death and heralds are sent to meet the army and ask for them to relinquish their weapons to the king.

- The generals of Cyrus's army and the officers of the Hellenes join forces to better their chances for returning home. The Hellenes are frightened by something in the night, which turns out to be nothing at all.

- The king asks for a truce and Clearchus asks for breakfast after establishing one. Clearchus says to Tissaphernes that the Hellenes only followed Cyrus's orders when they were attacking the king's authority.

- The Hellenes wait for Tissaphernes to return so they can leave. Tissaphernes comes with his troops and the Hellenes suspect they will be betrayed as they progress homeward.

- Clearchus trusts Tissaphernes enough to send generals, captains and some soldiers to his camp. This turns out to be a trap and Clearchus is killed and the generals do not return to the Hellenes's camp.

- All of the captured generals are decapitated and Xenophon describes their pasts and personalities.

Book III

[edit]- None of the Hellenes can sleep for fear of not returning home. Apollonides tries to persuade the Hellenes to go to the king to ask for a pardon.

- Xenophon tells the Hellenes to get rid of all but the necessities in order to travel homeward more efficiently.

- After crossing the river Zapatas, the Hellenes are attacked by Mithridates and find that they need better long-range weaponry.

- Tissaphernes comes after the Hellenes with a large contingent of troops. The Hellenes succeed in securing the summit first.

- The generals question their prisoners about the surrounding area and decide which direction to go after having reached the Tigris.

Book IV

[edit]

Trapezus (Trebizond) was the first Greek city the Ten Thousand reached on their retreat from inland Persia, 19th-c. illustration by Herman Vogel

- The Hellenes travel through the land of the Carduchii and lose two warriors when Cheirisophus does not slow for Xenophon on rearguard.

- The Hellenes progress slowly through the mountains with the Carduchii making it difficult to pass through the area. There is a struggle to gain control of the knolls and hilltops.

- Despairing, the Hellenes do not know what to do with the Carduchii closing in from behind and a deep river with a new enemy lying ahead of them until Xenophon has a dream.

- There is a heavy snowfall in Armenia and Tiribazus is following the Hellenes through his territory with a formidable army.

- The Hellenes face hardships in the snow. They are later overjoyed by the hospitality received in a village.

- The Hellenes confront an enemy in a mountain pass and Xenophon suggests taking control of the mountain before travelling up the pass.

- The Hellenes have a hard time overtaking the Taochian fortress. The soldiers finally catch a glimpse of the sea.

- Reaching a populous Hellenic city, Trapezus, the soldiers take a long rest and compete against each other in games.

Book V

[edit]- The soldiers vote to send Cheirisophus to a friend of his who lives nearby to get ships so they can sail home.

- The Hellenes are guided by the Trapezuntines to plunder provisions from the nearby Drilae.

- Cheirisophos returns but without enough ships to take them all back.

- The women and children, and those men who are sick or over the age of forty, are sent back on the ships to Hellas.

- Xenophon speaks of the temple he later constructs to Artemis in Scillus near Olympia.

- The Hellenes become allies with the Mossynoecians and agree to fight their foes together to pass through the territory.

- Xenophon persuades the ambassadors of Sinope into having good relations with the Hellenes.

- Taking the advice of Hecatonymus, the Hellenes take the sea route to reach Hellas.

- Slander is spread about Xenophon and his speech in defence of his honesty to the soldiers results in prosecutions of certain soldiers.

- Xenophon talks his way out of receiving punishment for beating a soldier.

Book VI

[edit]- The Hellenes make a deal with the Paphlagonians to cease fighting. Xenophon feels he should not be the leader on the last part of the trip.

- The army breaks up into three factions and Xenophon leads his troops back to Hellas.

- Xenophon hears of the situation the Arcadians and Achaeans are in and rushes with his troops to their aid.

- The Hellenes do not find the sacrificial victims in their favour and cannot proceed nor find provisions until the signs change in their favour.

- While waiting for the sacrifices to be in favour of their departure, 600 soldiers, while plunging a city for supplies, are killed by Pharnabazuse's soldiers. This is considered the biggest loss of soldiers during the Myrioi 's Anabasis.

- Xenophon advises the troops to attack their enemies now instead of waiting for the enemy to pursue them when they retreat to camp.

- Agasias is to be put on trial before Cleander for ordering Dexippus to be stoned after Agasias rescues one of his own from false accusation.

Book VII

[edit]- The Hellenes fight their way back into the city after learning of their planned expedition to Chersonese. Coeratadas' leadership falls through when he fails to give out enough rations for one day.

- Xenophon returns at the request of Anaxibius to the army after taking leave from the Hellenes for home.

- Xenophon works together with Seuthes to gain provisions for the Hellenes while Seuthes promises to pay them for gaining land for his control via the pillaged goods.

- Seuthes travels through the countryside burning villages and taking more territory with the Hellenes.

- Heracleides fails to come up with the full month's pay for the work done by the Hellenes. The blame is put on Xenophon.

- Xenophon speaks on the charges brought against him about not giving sufficient pay to the soldiers.

- Medosades gains control of the land the Hellenes helped to conquer and he threatens violence if the Hellenes don't cease pillaging his lands.

- Xenophon responds that the lack of promised payment and Seuthes' attitude will mean a new threat from him and his men if something isn't done.

- Seuthes pays a talent of silver and plentiful provisions to Xenophon, who distributes it to his troops.

- Xenophon finally returns home only to find he is wanted to help capture Asidates, which according to the soothsayer, Basias, should be easy.

- Asidates is captured with some difficulty.

Cultural influences

[edit]Educational use

[edit]Traditionally, Anabasis is one of the first unabridged texts studied by students of classical Greek, because of its clear and unadorned prose style in relatively pure Attic dialect—not unlike Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico for Latin students. Perhaps not coincidentally, they are both autobiographical tales of military adventure, told in the third person.[8]

Since the narrative mainly concerns a marching army, a common term used in Anabasis is ἐξελαύνω (exelauno), meaning "march out, march forth". Throughout the work, this term is used 23 times in the 3rd person singular present indicative active (ἐξελαύνει) and five additional times in other forms.[9] In the late 19th century, a tongue-in-cheek tradition arose among American students of Greek who were all too familiar with Xenophon's usage of this vocabulary item: March 4 (a date phonetically similar to the phrase "march forth") became known as "Exelauno Day".[10] The origin of this niche holiday is connected with the Roxbury Latin School in Massachusetts.[11]

Literary influence

[edit]Xenophon's book has inspired many literary and audio-visual works, both non-fiction and fiction.[citation needed]

Non-fiction

[edit]Non-fiction books inspired by Anabasis include:

The Anabasis of Alexander, by the Greek historian Arrian (86 – after 146 AD), is a history of the campaigns of Alexander the Great, specifically his conquest of the Persian Empire between 334 and 323 BC.[citation needed]

The Akhbār majmūʿa fī fatḥ al-Andalus ("Collection of Anecdotes on the Conquest of al-Andalus"), compiled in 11th-century Al-Andalus, makes use of the Anabasis as a literary embellishment, recording how, during the Abbasid Revolution, an army of ten thousand under a certain Balj marched to al-Andalus to support the Umayyad emir Abd ar-Rahman I.[12]

Shane Brennan's memoir In the Tracks of the Ten Thousand: A Journey on Foot through Turkey, Syria and Iraq (2005) recounts his 2000 journey to re-trace the steps of the Ten Thousand.[13]

Fiction

[edit]The cry of Xenophon's soldiers when they reach the sea ("Thalatta! Thalatta!") is mentioned in the second English translation of Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) when the expedition discovers an underground ocean (though the reference is absent from the original French text[14]).

The Sol Yurick novel The Warriors (1965) was directly based on Anabasis. The novel was adapted into the cult classic film The Warriors (1979).[15]

The Paul Davies novella Grace: A Story (1996) is a fantasy that details the progress of Xenophon's army through Armenia to Trabzon.[16]

Michael Curtis Ford wrote The Ten Thousand (2001); it follows Xenophon from his childhood until death.[17]

Valerio Massimo Manfredi's 2007 novel L'armata perduta (The Lost Army) tells the story of the army through Abira, a Syrian girl, who decides to follow a Greek warrior named Xeno (Xenophon).[18]

English translations and scholarly editions

[edit]- Xenophōntos Kyrou Anabaseōs : biblia hepta, edited by Thomas Hutchinson, E Typographeo Clarendoniano, Oxford, 1735.

- Anabasis, trans. by Edward Spelman, Esq., Harper & Brothers, New York, 1839.

- Anabasis, trans. by Rev. John Selby Watson, Henry G. Bohn, York Street, Covent Garden, 1854.

- The Anabasis of Xenophon: with an Interlinear Translation, trans. by Thomas Clark, David McKay Company, New York, 1887.

- Xenophon's Anabasis: Seven Books [Greek text for students], ed. by William Harper and James Wallace, American Book Co. 1893[19]

- The March of the Ten Thousand, trans. Henry Graham Dakyns, Macmillan, 1901.[20]

- Expeditio Cyri [Greek text], ed. by E. C. Marchant, Oxford Classical Texts, Oxford 1904, ISBN 0-19-814554-3

- Anabasis, trans. by C. L. Brownson, Loeb Classical Library, 1922, rev. 1989, ISBN 0-674-99101-X

- The March Up Country: A Translation of Xenophon's Anabasis into Plain English, trans. by W. H. D. Rouse, Nelson, London 1947.[21]

- The Persian Expedition, trans. by Rex Warner (1950), introduction by George Cawkwell (1972), Penguin Classics 2004 (ISBN 9780140440072).

- The Expedition of Cyrus, trans. by Robin Waterfield, Oxford World's Classics, Oxford, 2005, ISBN 0-19-282430-9

- The Anabasis of Cyrus, trans. by Wayne Ambler, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, 2008, ISBN 978-0-8014-8999-0

- The Landmark Xenophon's Anabasis, trans. by David Thomas, introduction by Shane Brennan, Pantheon Books, New York, 2021, ISBN 978-0-307-90685-4

References

[edit]- ^ Brownson, Carlson L. (Carleton Lewis) (1886). Xenophon;. Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. A Greek-English Lexicon on Perseus.

- ^ Durant, Will (1939). The Story of Civilization Volume 2: The Life of Greece. Simon & Schuster. pp. 460–61.

- ^ Hellen, iii, i, 2 cited in William Mitford; Baron John Mitford Redesdale (1838). The History of Greece. T. Cadell. p. 297.

- ^ Xenophon (1854). The Anabasis, Or Expedition of Cyrus: And the Memorabilia of Socrates. H. G. Bohn. p. v.

- ^ The cry, written in Greek as θαλασσα, θαλασσα, is conventionally rendered "Thalassa, thalassa!" in English. Thalatta was the Attic pronunciation, which had -tt- where the written language, as well as spoken Ionic, Doric and Modern Greek, has -ss-.

- ^ Jason of Pherae's plans of a "panhellenic conquest of Persia" (following the Anabasis), which Xenophon, in his Hellenica but also Isocrates, in his speech addressed directly to Phillip, recount, probably had an influence on the Macedonian king.

- ^ cf. Albrecht, Michael v.: Geschichte der römischen Literatur Band 1 (History of Roman Literature, Volume 1). Munich 1994, 2nd ed., pp. 332–334.

- ^ The count can be obtained by searching the lemma on the website of the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae: http://stephanus.tlg.uci.edu/

- ^ "Students celebrate Exelauno Day".

- ^ "Exelauno Day 2019". 2019-03-06.

- ^ Emilio González-Ferrín, "Al-Andalus: The First Enlightenment", Critical Muslim, 6 (2013), p. 5.

- ^ Brennan, Shane (2005). In the Tracks of the Ten Thousand: A Journey on Foot through Turkey, Syria and Iraq. London: Robert Hale.

- ^ Verne, Jules (1864). Voyage au centre de la Terre (1st ed.). Paris: Hetzel. p. 220. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ Almagor, Eran (2017). "Going Home: Xenophon's Anabasis in Sol Yurick's The Warriors (1965)". Rewriting the Ancient World: Greeks, Romans, Jews and Christians in modern popular fiction. Leiden: Brill. pp. 85–113. ISBN 9789004346383.

- ^ Davies, Paul (1996). Grace: A Story. Toronto: ECW Press. ISBN 9781550222753.

- ^ Ford, Michael Curtis (2001). The Ten Thousand. New York: Thomas Dune Books. ISBN 0312269463.

- ^ Massimo Manfredi, Valerio (2007). L'armata perduta. Milano: Arnoldo Mondadori Editore. ISBN 978-90-218-0138-4.

- ^ Xenophon; Harper, William Rainey; Wallace, James (1893). Xenophon's Anabasis, seven books . University of California Libraries. New York, Cincinnati [etc.] : American book company.

- ^ H. G. Dakyns (1901-01-01). The March of the Ten Thousand - Being a Translation of the Anabasis Preceded By a Life of Xenophon. Internet Archive. MacMillan & Co.

- ^ Xenophon; Rouse, W. H. D. (William Henry Denham) (1958). The march up country : a translation of Xenophon's Anabasis. Internet Archive. Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link)

Bibliography

[edit]- Bassett, S. R. "Innocent Victims or Perjurers Betrayed? The Arrest of the Generals in Xenophon's 'Anabasis'." The Classical Quarterly, vol. 52, no. 2, 2002, pp. 447–461.

- Bradley, P. "Xenophon's Anabasis: Reading the End with Zeus the Merciful". Arethusa 44(3), 279–310. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011.

- Brennan, S. "Chronological Pointers in Xenophon's 'Anabasis'." Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, vol. 51, 2008, pp. 51–61.

- Burckhardt, L. Militärgeschichte der Antike. Beck'schen Reihe; 2447. München: Verlag C. H. Beck, 2008.

- Buzzetti, E. Xenophon: The Socratic Prince: The Argument of the Anabasis of Cyrus. Recovering Political Philosophy . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

- Flower, M. A. Xenophon's Anabasis, or the Expedition of Cyrus. Oxford Approaches to Classical Literature. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Lane Fox, R., ed. The Long March: Xenophon and the Ten Thousand. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2004.

- Lee, J. W. I. A Greek Army on the March: Soldiers and Survival in Xenophon's Anabasis. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Nussbaum, G. B. The Ten Thousand: A Study in Social Organization and Action in Xenophon's Anabasis. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1967.

- Rood, T. "Space and Landscape in Xenophon's Anabasis". In Kate Gilhuly & Nancy Worman (eds.), (pp. 63–93). Space, Place, and Landscape in Ancient Greek Literature and Culture. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Xenophon's Retreat by Robin Waterfield is an accessible companion for anyone needing to be filled in on the historical, military and political background. Faber & Faber, 2006, ISBN 978-0-674-02356-7

KSF

KSF