Aromatic compound

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 18 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 18 min

Aromatic compounds or arenes are organic compounds "with a chemistry typified by benzene" and "cyclically conjugated."[1] The word "aromatic" originates from the past grouping of molecules based on odor, before their general chemical properties were understood. The current definition of aromatic compounds does not have any relation to their odor. Aromatic compounds are now defined as cyclic compounds satisfying Hückel's rule. Aromatic compounds have the following general properties:

- Typically unreactive

- Often non polar and hydrophobic

- High carbon-hydrogen ratio

- Burn with a strong sooty yellow flame, due to high C:H ratio

- Undergo electrophilic substitution reactions and nucleophilic aromatic substitutions[2]

Arenes are typically split into two categories - benzoids, that contain a benzene derivative and follow the benzene ring model, and non-benzoids that contain other aromatic cyclic derivatives. Aromatic compounds are commonly used in organic synthesis and are involved in many reaction types, following both additions and removals, as well as saturation and dearomatization.

Heteroarenes

[edit]Heteroarenes are aromatic compounds, where at least one methine or vinylene (-C= or -CH=CH-) group is replaced by a heteroatom: oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur.[3] Examples of non-benzene compounds with aromatic properties are furan, a heterocyclic compound with a five-membered ring that includes a single oxygen atom, and pyridine, a heterocyclic compound with a six-membered ring containing one nitrogen atom. Hydrocarbons without an aromatic ring are called aliphatic. Approximately half of compounds known in 2000 are described as aromatic to some extent.[4]

Applications

[edit]Aromatic compounds are pervasive in nature and industry. Key industrial aromatic hydrocarbons are benzene, toluene, xylene called BTX. Many biomolecules have phenyl groups including the so-called aromatic amino acids.

Benzene ring model

[edit]

Benzene, C6H6, is the least complex aromatic hydrocarbon, and it was the first one defined as such.[6] Its bonding nature was first recognized independently by Joseph Loschmidt and August Kekulé in the 19th century.[6] Each carbon atom in the hexagonal cycle has four electrons to share. One electron forms a sigma bond with the hydrogen atom, and one is used in covalently bonding to each of the two neighboring carbons. This leaves six electrons, shared equally around the ring in delocalized pi molecular orbitals the size of the ring itself.[5] This represents the equivalent nature of the six carbon-carbon bonds all of bond order 1.5. This equivalency can also explained by resonance forms.[5] The electrons are visualized as floating above and below the ring, with the electromagnetic fields they generate acting to keep the ring flat.[5]

The circle symbol for aromaticity was introduced by Sir Robert Robinson and his student James Armit in 1925 and popularized starting in 1959 by the Morrison & Boyd textbook on organic chemistry.[7] The proper use of the symbol is debated: some publications use it to any cyclic π system, while others use it only for those π systems that obey Hückel's rule. Some argue that, in order to stay in line with Robinson's originally intended proposal, the use of the circle symbol should be limited to monocyclic 6 π-electron systems.[8] In this way the circle symbol for a six-center six-electron bond can be compared to the Y symbol for a three-center two-electron bond.[8]

Benzene and derivatives of benzene

[edit]

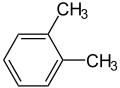

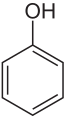

Benzene derivatives have from one to six substituents attached to the central benzene core.[2] Examples of benzene compounds with just one substituent are phenol, which carries a hydroxyl group, and toluene with a methyl group. When there is more than one substituent present on the ring, their spatial relationship becomes important for which the arene substitution patterns ortho, meta, and para are devised.[9] When reacting to form more complex benzene derivatives, the substituents on a benzene ring can be described as either activated or deactivated, which are electron donating and electron withdrawing respectively.[9] Activators are known as ortho-para directors, and deactivators are known as meta directors.[9] Upon reacting, substituents will be added at the ortho, para or meta positions, depending on the directivity of the current substituents to make more complex benzene derivatives, often with several isomers. Electron flow leading to re-aromatization is key in ensuring the stability of such products.[9]

For example, three isomers exist for cresol because the methyl group and the hydroxyl group (both ortho para directors) can be placed next to each other (ortho), one position removed from each other (meta), or two positions removed from each other (para).[10] Given that both the methyl and hydroxyl group are ortho-para directors, the ortho and para isomers are typically favoured.[10] Xylenol has two methyl groups in addition to the hydroxyl group, and, for this structure, 6 isomers exist.[citation needed]

Arene rings can stabilize charges, as seen in, for example, phenol (C6H5–OH), which is acidic at the hydroxyl (OH), as charge on the oxygen (alkoxide –O−) is partially delocalized into the benzene ring.

- Representative arene compounds

Non-benzylic arenes

[edit]Although benzylic arenes are common, non-benzylic compounds are also exceedingly important. Any compound containing a cyclic portion that conforms to Hückel's rule and is not a benzene derivative can be considered a non-benzylic aromatic compound.[5]

Monocyclic arenes

[edit]Of annulenes larger than benzene, [12]annulene and [14]annulene are weakly aromatic compounds and [18]annulene, Cyclooctadecanonaene, is aromatic, though strain within the structure causes a slight deviation from the precisely planar structure necessary for aromatic categorization.[11] Another example of a non-benzylic monocyclic arene is the cyclopropenyl (cyclopropenium cation), which satisfies Hückel's rule with an n equal to 0.[12] Note, only the cationic form of this cyclic propenyl is aromatic, given that neutrality in this compound would violate either the octet rule or Hückel's rule.[12]

Other non-benzylic monocyclic arenes include the aforementioned heteroarenes that can replace carbon atoms with other heteroatoms such as N, O or S.[5] Common examples of these are the five-membered pyrrole and six-membered pyridine, both of which have a substituted nitrogen[13]

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

[edit]

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, also known as polynuclear aromatic compounds (PAHs) are aromatic hydrocarbons that consist of fused aromatic rings and do not contain heteroatoms or carry substituents.[14] Naphthalene is the simplest example of a PAH. PAHs occur in oil, coal, and tar deposits, and are produced as byproducts of fuel burning (whether fossil fuel or biomass).[15] As pollutants, they are of concern because some compounds have been identified as carcinogenic, mutagenic, and teratogenic.[16][17][18][19] PAHs are also found in cooked foods.[15] Studies have shown that high levels of PAHs are found, for example, in meat cooked at high temperatures such as grilling or barbecuing, and in smoked fish.[15][16] They are also a good candidate molecule to act as a basis for the earliest forms of life.[20] In graphene the PAH motif is extended to large 2D sheets.[21]

Reactions

[edit]Aromatic ring systems participate in many organic reactions.

Substitution

[edit]In aromatic substitution, one substituent on the arene ring, usually hydrogen, is replaced by another reagent.[5] The two main types are electrophilic aromatic substitution, when the active reagent is an electrophile, and nucleophilic aromatic substitution, when the reagent is a nucleophile. In radical-nucleophilic aromatic substitution, the active reagent is a radical.[22][23]

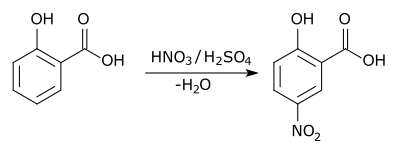

An example of electrophilic aromatic substitution is the nitration of salicylic acid, where a nitro group is added para to the hydroxide substituent:

Nucleophilic aromatic substitution involves displacement of a leaving group, such as a halide, on an aromatic ring. Aromatic rings usually nucleophilic, but in the presence of electron-withdrawing groups aromatic compounds undergo nucleophilic substitution. Mechanistically, this reaction differs from a common SN2 reaction, because it occurs at a trigonal carbon atom (sp2 hybridization).[24]

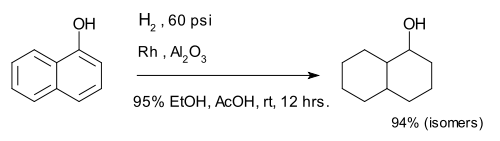

Hydrogenation

[edit]Hydrogenation of arenes create saturated rings. The compound 1-naphthol is completely reduced to a mixture of decalin-ol isomers.[25]

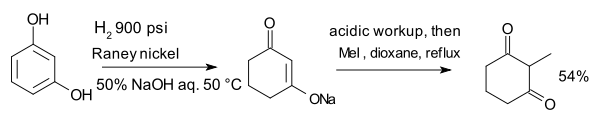

The compound resorcinol, hydrogenated with Raney nickel in presence of aqueous sodium hydroxide forms an enolate which is alkylated with methyl iodide to 2-methyl-1,3-cyclohexandione:[26]

Dearomatization

[edit]In dearomatization reactions the aromaticity of the reactant is lost. In this regard, the dearomatization is related to hydrogenation. A classic approach is Birch reduction. The methodology is used in synthesis.[27]

Arene-arene interactions

[edit]Arene-arene interactions have attracted much attention. Pi-stacking (also called π–π stacking) refers to the presumptively attractive, noncovalent pi interactions between the pi bonds of aromatic rings, because of orbital overlap.[29] According to some authors direct stacking of aromatic rings (the "sandwich interaction") is electrostatically repulsive.

More commonly observed are either a staggered stacking (parallel displaced) or pi-teeing (perpendicular T-shaped) interaction both of which are electrostatic attractive[30][31] For example, the most commonly observed interactions between aromatic rings of amino acid residues in proteins is a staggered stacked followed by a perpendicular orientation. Sandwiched orientations are relatively rare.[32]

Pi stacking is repulsive as it places carbon atoms with partial negative charges from one ring on top of other partial negatively charged carbon atoms from the second ring and hydrogen atoms with partial positive charges on top of other hydrogen atoms that likewise carry partial positive charges.[30] In staggered stacking, one of the two aromatic rings is offset sideways so that the carbon atoms with partial negative charge in the first ring are placed above hydrogen atoms with partial positive charge in the second ring so that the electrostatic interactions become attractive. Likewise, pi-teeing interactions in which the two rings are oriented perpendicular to either other is electrostatically attractive as it places partial positively charged hydrogen atoms in close proximity to partially negatively charged carbon atoms. An alternative explanation for the preference for staggered stacking is due to the balance between van der Waals interactions (attractive dispersion plus Pauli repulsion).[33]

These staggered stacking and π-teeing interactions between aromatic rings are important in nucleobase stacking within DNA and RNA molecules, protein folding, template-directed synthesis, materials science, and molecular recognition. Despite the wide use of term pi stacking in the scientific literature, there is no theoretical justification for its use.[30]

Benzene dimer

[edit]

The benzene dimer is the prototypical system for the study of pi stacking, and is experimentally bound by 8–12 kJ/mol (2–3 kcal/mol) in the gas phase with a separation of 4.96 Å between the centers of mass for the T-shaped dimer.[34] X-ray crystallography reveals perpendicular and offset parallel configurations for many simple aromatic compounds.[34] Similar offset parallel or perpendicular geometries were observed in a survey of high-resolution x-ray protein crystal structures in the Protein Data Bank.[35] Analysis of the aromatic amino acids phenylalanine, tyrosine, histidine, and tryptophan indicates that dimers of these side chains have many stabilizing interactions at distances larger than the average van der Waals radii.[32]

The relative binding energies of the three geometries of the benzene dimer can be explained by a balance of quadrupole/quadrupole and London dispersion forces. While benzene does not have a dipole moment, it has a strong quadrupole moment.[36] The local C–H dipole means that there is positive charge on the atoms in the ring and a correspondingly negative charge representing an electron cloud above and below the ring. The quadrupole moment is reversed for hexafluorobenzene due to the electronegativity of fluorine. The benzene dimer in the sandwich configuration is stabilized by London dispersion forces but destabilized by repulsive quadrupole/quadrupole interactions. By offsetting one of the benzene rings, the parallel displaced configuration reduces these repulsive interactions and is stabilized. The large polarizability of aromatic rings lead to dispersive interactions as major contribution to stacking effects. These play a major role for interactions of nucleobases e.g. in DNA.[37] The T-shaped configuration enjoys favorable quadrupole/quadrupole interactions, as the positive quadrupole of one benzene ring interacts with the negative quadrupole of the other. The benzene rings are furthest apart in this configuration, so the favorable quadrupole/quadrupole interactions evidently compensate for diminished dispersion forces.

According to one model, electron-withdrawing substituents lowers the negative quadrupole of the aromatic ring and thereby favor parallel displaced and sandwich conformations. By contrast, electron donating groups increase the negative quadrupole, which may stabilize a T-shaped configuration with the proper geometry.[38] They used a simple mathematical model based on sigma and pi atomic charges, relative orientations, and van der Waals interactions to qualitatively determine that electrostatics are dominant in substituent effects.[39]

Hunter et al. applied a more sophisticated chemical double mutant cycle with a hydrogen-bonded "zipper" to the issue of substituent effects in pi stacking interactions in proteins.[40] [41] However, the authors note that direct interactions with the ring substituents, discussed below, also make important contributions. Indeed, the interplay of these two factors may result in the complicated substituent- and geometry-dependent behavior of pi stacking interactions.

Some experimental and computational evidence suggests that pi stacking interactions are not governed primarily by electrostatic effects.[42].[43]

The relative contributions pi stacking have been borne out by computation.[44][45][46] Trends based on electron donating or withdrawing substituents can be explained by exchange-repulsion and dispersion terms.[47]

A molecular torsion balance from an aryl ester with two conformational states.[48] The folded state had a well-defined pi stacking interaction with a T-shaped geometry, whereas the unfolded state had no aryl–aryl interactions. The NMR chemical shifts of the two conformations were distinct and could be used to determine the ratio of the two states, which was interpreted as a measure of intramolecular forces. The authors report that a preference for the folded state is not unique to aryl esters. For example, the cyclohexyl ester favored the folded state more so than the phenyl ester, and the tert-butyl ester favored the folded state by a preference greater than that shown by any aryl ester. This suggests that aromaticity is not a strict requirement for favorable interaction with an aromatic ring.

Other evidence for non-aromatic pi stacking interactions results include critical studies in theoretical chemistry, explaining the underlying mechanisms of empirical observations. Grimme reported that the interaction energies of smaller dimers consisting of one or two rings are very similar for both aromatic and saturated compounds.[49] This finding is of particular relevance to biology, and suggests that the contribution of pi systems to phenomena such as stacked nucleobases may be overestimated. However, it was shown that an increased stabilizing interaction is seen for large aromatic dimers. As previously noted, this interaction energy is highly dependent on geometry. Indeed, large aromatic dimers are only stabilized relative to their saturated counterparts in a sandwich geometry, while their energies are similar in a T-shaped interaction.

A more direct approach to modeling the role of aromaticity was taken by Bloom and Wheeler.[50] The authors compared the interactions between benzene and either 2-methylnaphthalene or its non-aromatic isomer, 2-methylene-2,3-dihydronaphthalene. The latter compound provides a means of conserving the number of p-electrons while, however, removing the effects of delocalization. Surprisingly, the interaction energies with benzene are higher for the non-aromatic compound, suggesting that pi-bond localization is favorable in pi stacking interactions. The authors also considered a homodesmotic dissection of benzene into ethylene and 1,3-butadiene and compared these interactions in a sandwich with benzene. Their calculation indicates that the interaction energy between benzene and homodesmotic benzene is higher than that of a benzene dimer in both sandwich and parallel displaced conformations, again highlighting the favorability of localized pi-bond interactions. These results strongly suggest that aromaticity is not required for pi stacking interactions in this model.

Even in light of this evidence, Grimme concludes that pi stacking does indeed exist.[49] However, he cautions that smaller rings, particularly those in T-shaped conformations, do not behave significantly differently from their saturated counterparts, and that the term should be specified for larger rings in stacked conformations which do seem to exhibit a cooperative pi electron effect.

See also

[edit]- Aromatic substituents: Aryl, Aryloxy and Arenediyl

- Asphaltene

- Hydrodealkylation

- Simple aromatic rings

References

[edit]- ^ "Aromatic". IUPAC GoldBook. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ a b Smith, Michael B.; March, Jerry (2007), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 978-0-471-72091-1

- ^ IUPAC. Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book"). Compiled by A. D. McNaught and A. Wilkinson. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford (1997). Online version (2019-) created by S. J. Chalk. ISBN 0-9678550-9-8. https://doi.org/10.1351/goldbook.

- ^ Balaban, Alexandru T.; Oniciu, Daniela C.; Katritzky, Alan R. (2004-05-01). "Aromaticity as a Cornerstone of Heterocyclic Chemistry". Chemical Reviews. 104 (5): 2777–2812. doi:10.1021/cr0306790. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 15137807.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Klein, David R. (2017). Organic Chemistry (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119444251.

- ^ a b "Benzene | Definition, Discovery, Structure, Properties, & Uses | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ Armit, James Wilson; Robinson, Robert (1925). "CCXI.—Polynuclear heterocyclic aromatic types. Part II. Some anhydronium bases". J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 127: 1604–1618. doi:10.1039/CT9252701604. ISSN 0368-1645.

- ^ a b Jensen, William B. (April 2009). "The Origin of the Circle Symbol for Aromaticity". Journal of Chemical Education. 86 (4): 423. Bibcode:2009JChEd..86..423J. doi:10.1021/ed086p423. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ^ a b c d "16.5: An Explanation of Substituent Effects". Chemistry LibreTexts. 2015-05-03. Retrieved 2023-12-03.

- ^ a b Badanthadka, M.; Mehendale, H.M. (2014). "Cresols". Encyclopedia of Toxicology. pp. 1061–1065. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-386454-3.00296-7. ISBN 978-0-12-386455-0.

- ^ "What does "aromatic" really mean?". Chemistry LibreTexts. 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ a b "What does "aromatic" really mean?". Chemistry LibreTexts. 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ^ "4.2: Covalent Bonds". Chemistry LibreTexts. 2020-07-30. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ Fetzer, John C. (2007-04-16). "THE CHEMISTRY AND ANALYSIS OF LARGE PAHs". Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds. 27 (2): 143–162. doi:10.1080/10406630701268255. ISSN 1040-6638. S2CID 97930473.

- ^ a b c "Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons – Occurrence in foods, dietary exposure and health effects" (PDF). European Commission, Scientific Committee on Food. December 4, 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ a b Larsson, Bonny K.; Sahlberg, Greger P.; Eriksson, Anders T.; Busk, Leif A. (July 1983). "Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in grilled food". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 31 (4): 867–873. Bibcode:1983JAFC...31..867L. doi:10.1021/jf00118a049. ISSN 0021-8561. PMID 6352775.

- ^ Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain on a request from the European Commission on Marine Biotoxins in Shellfish – Saxitoxin Group. The EFSA Journal (2009) 1019, 1-76.

- ^ Keith, Lawrence H. (2015-03-15). "The Source of U.S. EPA's Sixteen PAH Priority Pollutants". Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds. 35 (2–4): 147–160. doi:10.1080/10406638.2014.892886. ISSN 1040-6638.

- ^ Thomas, Philippe J.; Newell, Emily E.; Eccles, Kristin; Holloway, Alison C.; Idowu, Ifeoluwa; Xia, Zhe; Hassan, Elizabeth; Tomy, Gregg; Quenneville, Cheryl (2021-02-01). "Co-exposures to trace elements and polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs) impacts North American river otter (Lontra canadensis) baculum". Chemosphere. 265: 128920. Bibcode:2021Chmsp.26528920T. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128920. ISSN 0045-6535. PMID 33213878.

- ^ Ehrenfreund, Pascale; Rasmussen, Steen; Cleaves, James; Chen, Liaohai (June 2006). "Experimentally Tracing the Key Steps in the Origin of Life: The Aromatic World". Astrobiology. 6 (3): 490–520. Bibcode:2006AsBio...6..490E. doi:10.1089/ast.2006.6.490. ISSN 1531-1074. PMID 16805704.

- ^ Wang, Xiao-Ye; Yao, Xuelin; Müllen, Klaus (2019-09-01). "Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the graphene era". Science China Chemistry. 62 (9): 1099–1144. doi:10.1007/s11426-019-9491-2. hdl:21.11116/0000-0004-B547-0. ISSN 1869-1870. S2CID 198333072.

- ^ "22.4: Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution". Chemistry LibreTexts. 2014-11-26. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ^ "16.7: Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution". Chemistry LibreTexts. 2015-05-03. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ^ Clayden, Jonathan; Greeves, Nick; Warren, Stuart (2012-03-15). Organic Chemistry (Second ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 514–515. ISBN 978-0-19-927029-3.

- ^ Meyers, A. I.; Beverung, W. N.; Gault, R. "1-Naphthol". Organic Syntheses. 51: 103; Collected Volumes, vol. 6.

- ^ Noland, Wayland E.; Baude, Frederic J. "Ethyl Indole-2-carboxylate". Organic Syntheses. 41: 56; Collected Volumes, vol. 5.

- ^ Roche, Stéphane P.; Porco, John A. (2011-04-26). "Dearomatization Strategies in the Synthesis of Complex Natural Products". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 50 (18): 4068–4093. doi:10.1002/anie.201006017. ISSN 1433-7851. PMC 4136767. PMID 21506209.

- ^ Zheng, Chao; You, Shu-Li (2021-03-24). "Advances in Catalytic Asymmetric Dearomatization". ACS Central Science. 7 (3): 432–444. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.0c01651. ISSN 2374-7943. PMC 8006174. PMID 33791426.

- ^ Smith, Michael B.; March, Jerry (2007), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, p. 114, ISBN 978-0-471-72091-1

- ^ a b c Martinez CR, Iverson BL (2012). "Rethinking the term "pi-stacking"". Chemical Science. 3 (7): 2191. doi:10.1039/c2sc20045g. hdl:2152/41033. ISSN 2041-6520. S2CID 95789541.

- ^ Lewis M, Bagwill C, Hardebeck L, Wireduaah S (2016). "Modern Computational Approaches to Understanding Interactions of Aromatics". In Johnson DW, Hof F (eds.). Aromatic Interactions: Frontiers in Knowledge and Application. England: Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-1-78262-662-6.

- ^ a b McGaughey GB, Gagné M, Rappé AK (June 1998). "pi-Stacking interactions. Alive and well in proteins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (25): 15458–63. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.25.15458. PMID 9624131.

- ^ Carter-Fenk K, Herbert JM (November 2020). "Reinterpreting π-stacking". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 22 (43): 24870–24886. Bibcode:2020PCCP...2224870C. doi:10.1039/d0cp05039c. PMID 33107520. S2CID 225083299.

- ^ a b Sinnokrot MO, Valeev EF, Sherrill CD (September 2002). "Estimates of the ab initio limit for pi-pi interactions: the benzene dimer". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 124 (36): 10887–10893. doi:10.1021/ja025896h. PMID 12207544.

- ^ Huber RG, Margreiter MA, Fuchs JE, von Grafenstein S, Tautermann CS, Liedl KR, Fox T (May 2014). "Heteroaromatic π-stacking energy landscapes". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 54 (5): 1371–1379. doi:10.1021/ci500183u. PMC 4037317. PMID 24773380.

- ^ Battaglia MR, Buckingham AD, Williams JH (1981). "The electric quadrupole moments of benzene and hexafluorobenzene". Chem. Phys. Lett. 78 (3): 421–423. Bibcode:1981CPL....78..421B. doi:10.1016/0009-2614(81)85228-1.

- ^ Riley KE, Hobza P (April 2013). "On the importance and origin of aromatic interactions in chemistry and biodisciplines". Accounts of Chemical Research. 46 (4): 927–936. doi:10.1021/ar300083h. PMID 22872015.

- ^ Hunter CA, Sanders JK (1990). "The nature of π–π Interactions". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112 (14): 5525–5534. Bibcode:1990JAChS.112.5525H. doi:10.1021/ja00170a016.

- ^ Cozzi F, Cinquini M, Annuziata R, Siegel JS (1993). "Dominance of polar/.pi. Over charge-transfer effects in stacked phenyl interactions". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115 (12): 5330–5331. Bibcode:1993JAChS.115.5330C. doi:10.1021/ja00065a069.

- ^ a b Cockroft SL, Hunter CA, Lawson KR, Perkins J, Urch CJ (June 2005). "Electrostatic control of aromatic stacking interactions". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (24): 8594–8595. Bibcode:2005JAChS.127.8594C. doi:10.1021/ja050880n. PMID 15954755.

- ^ Cockroft SL, Perkins J, Zonta C, Adams H, Spey SE, Low CM, et al. (April 2007). "Substituent effects on aromatic stacking interactions". Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 5 (7): 1062–1080. doi:10.1039/b617576g. PMID 17377660. S2CID 37409177.

- ^ Martinez, Chelsea R.; Iverson, Brent L. (2012). "Rethinking the term "pi-stacking"". Chemical Science. 3 (7): 2191. doi:10.1039/C2SC20045G. hdl:2152/41033.

- ^ Rashkin MJ, Waters ML (March 2002). "Unexpected substituent effects in offset pi-pi stacked interactions in water". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 124 (9): 1860–1861. doi:10.1021/ja016508z. PMID 11866592.

- ^ a b Wheeler SE, Houk KN (August 2008). "Substituent effects in the benzene dimer are due to direct interactions of the substituents with the unsubstituted benzene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 130 (33): 10854–10855. Bibcode:2008JAChS.13010854W. doi:10.1021/ja802849j. PMC 2655233. PMID 18652453.

- ^ Sinnokrot MO, Sherrill CD (2003). "Unexpected Substituent Effects in Face-to-Face π-Stacking Interactions". J. Phys. Chem. A. 107 (41): 8377–8379. Bibcode:2003JPCA..107.8377S. doi:10.1021/jp030880e.

- ^ Ringer AL, Sinnokrot MO, Lively RP, Sherrill CD (May 2006). "The effect of multiple substituents on sandwich and T-shaped pi-pi interactions". Chemistry: A European Journal. 12 (14): 3821–3828. doi:10.1002/chem.200501316. PMID 16514687.

- ^ Sinnokrot MO, Sherrill CD (September 2006). "High-accuracy quantum mechanical studies of pi-pi interactions in benzene dimers". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 110 (37): 10656–10668. Bibcode:2006JPCA..11010656S. doi:10.1021/jp0610416. PMID 16970354.

- ^ Paliwal S, Geib S, Wilcox CS (1994). "Molecular Torsion Balance for Weak Molecular Recognition Forces. Effects of "Tilted-T" Edge-to-Face Aromatic Interactions on Conformational Selection and Solid-State Structure". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116 (10): 4497–4498. Bibcode:1994JAChS.116.4497P. doi:10.1021/ja00089a057.

- ^ a b Grimme S (2008). "Do special noncovalent pi-pi stacking interactions really exist?". Angewandte Chemie. 47 (18): 3430–3434. doi:10.1002/anie.200705157. PMID 18350534.

- ^ a b Bloom JW, Wheeler SE (2011). "Taking the Aromaticity out of Aromatic Interactions". Angew. Chem. 123 (34): 7993–7995. Bibcode:2011AngCh.123.7993B. doi:10.1002/ange.201102982.

External links

[edit] Media related to aromatic compounds at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to aromatic compounds at Wikimedia Commons

KSF

KSF