Art of the Middle Paleolithic

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

The oldest undisputed examples of figurative art are known from Europe and from Sulawesi, Indonesia, and are dated as far back as around 50,000 years ago (Art of the Upper Paleolithic).[1] Together with religion and other cultural universals of contemporary human societies, the emergence of figurative art is a necessary attribute of full behavioral modernity.

There are, however, some examples of non-figurative designs which somewhat predate the Upper Paleolithic, beginning about 70,000 years ago (MIS 4). These include the earliest of the Iberian cave paintings, including a hand stencil at the Cave of Maltravieso, a simple linear design, and red paint applied to speleothems, dated to at least 64,000 years ago and as such attributable to Neanderthals.[2] The markings on the walls of a cave in La Roche-Cotard in the Loire valley have been identified as the oldest known Neanderthal engravings and have been dated to more than 57,000 years ago.[3][4] Similarly, the Blombos Cave of South Africa yielded some stones with engraved grid or cross-hatch patterns, dated to some 73,000 years ago, but they are attributed to Homo sapiens.[5]

Europe

[edit]The 130,000-year-old eagle claws found in Krapina, Croatia, have been viewed by some anthropologists as an example of Neanderthal art. Some have suggested that Neanderthals may have copied this behavior from Homo sapiens. But David W. Frayer has disputed this view, saying that Homo sapiens were not in the region where claws were discovered even after 100,000 years.[8]

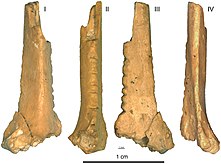

In Spain, Uranium-thorium dating of painted designs in the caves of La Pasiega (Cantabria), a hand stencil in Maltravieso (Extremadura), and red-painted speleothems in Ardales (Andalusia) yielded an age of more than 64,800 years, predating the previously oldest known art by at least 20,000 years.[2] In July 2021, scientists reported the discovery of a bone carving, one of the world's oldest works of art, made by Neanderthals about 51,000 years ago.[9][10]

The Mask of La Roche-Cotard has also been argued as being evidence of Neanderthal figurative art, although in a period post-dating their contact with Homo sapiens. The "Divje Babe flute" had controversially been claimed as a Neanderthal musical instrument, though many researchers believe that its holes are most likely the bite marks of carnivores.[11][12]

Southern Africa

[edit]

In 2002 in Blombos cave, situated in South Africa, ochre stones were discovered engraved with grid or cross-hatch patterns, dated to some 70,000 years ago. This suggested to some researchers that early Homo sapiens were capable of abstraction and production of abstract art or symbolic art. Also discovered at the Blombos cave were shell beads, also dating to c. 70,000 years ago.[13] Engraved ochre has also been reported from other Middle Stone Age sites, such as Klein Kliphuis,[14] Wonderwerk Cave[15] and Klasies River Cave 1.[16] Arguably, these engraved pieces of ochre represent – together with the engraved ostrich egg shells from Diepkloof[17][18] – the earliest forms of abstract representation and conventional design tradition hitherto recorded. The interpretation of the hatching patterns as "symbolic" has been challenged, and several purely functional explanations of the objects have been proposed, e.g. as an ingredient in mastic, skin protection against sun or insects, as soft-hammers for delicate knapping, as a hide preservative or as medicine.[19][20][21][22] The Blombos Cave cross-hatches, dated to as early as 73,000 years old, have been described as "abstract drawings" in a 2018 publication.[5]

Claimed Lower Paleolithic art

[edit]

A 500,000-year-old Pseudodon shell DUB1006-fL found in Java in the 1890s, associated with Homo erectus, contains the earliest known geometric engravings.[23] Although some commentators express an opinion that this could be the earliest evidence of artistic expression of hominids, the actual meaning and intent behind these engravings are not known.[23]

Homo erectus had long before produced seemingly aimless patterns on artifacts such as is those found at Bilzingsleben in Thuringia. Some have attempted to interpret these as a precursor to art, allegedly revealing the intent of the maker to decorate and fashion. The symmetry and attention given to the shape of a tool has led authors to controversially argue Acheulean hand axes as artistic expressions.

There are several other claims of Lower Paleolithic art, namely the "Venus of Tan-Tan" (before 300 kya)[24] and the "Venus of Berekhat Ram" (250 kya). Both of these may be natural rock formations with an incidental likeness to the human form, but some scholars have suggested that they exhibit traces of pigments or carving intended to further accentuate the human-like form.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ M. Aubert et al., "Pleistocene cave art from Sulawesi, Indonesia", Nature volume 514, pages 223–227 (09 October 2014). "using uranium-series dating of coralloid speleothems directly associated with 12 human hand stencils and two figurative animal depictions from seven cave sites in the Maros karsts of Sulawesi, we show that rock art traditions on this Indonesian island are at least compatible in age with the oldest European art. The earliest dated image from Maros, with a minimum age of 39.9 kyr, is now the oldest known hand stencil in the world. In addition, a painting of a babirusa ('pig-deer') made at least 35.4 kyr ago is among the earliest dated figurative depictions worldwide, if not the earliest one. Among the implications, it can now be demonstrated that humans were producing rock art by ~40 kyr ago at opposite ends of the Pleistocene Eurasian world."

- ^ a b D. L. Hoffmann; C. D. Standish; M. García-Diez; P. B. Pettitt; J. A. Milton; J. Zilhão; J. J. Alcolea-González; P. Cantalejo-Duarte; H. Collado; R. de Balbín; M. Lorblanchet; J. Ramos-Muñoz; G.-Ch. Weniger; A. W. G. Pike (2018). "U-Th dating of carbonate crusts reveals Neandertal origin of Iberian cave art". Science. 359 (6378): 912–915. Bibcode:2018Sci...359..912H. doi:10.1126/science.aap7778. hdl:10498/21578. PMID 29472483. "we present dating results for three sites in Spain that show that cave art emerged in Iberia substantially earlier than previously thought. Uranium-thorium (U-Th) dates on carbonate crusts overlying paintings provide minimum ages for a red linear motif in La Pasiega (Cantabria), a hand stencil in Maltravieso (Extremadura), and red-painted speleothems in Ardales (Andalucía). Collectively, these results show that cave art in Iberia is older than 64.8 thousand years (ka). This cave art is the earliest dated so far and predates, by at least 20 ka, the arrival of modern humans in Europe, which implies Neandertal authorship."

- ^ Sample, Ian (21 June 2023). "French cave markings said to be oldest known engravings by Neanderthals". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 21 June 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ Marquet, Jean-Claude; Freiesleben, Trine Holm; Thomsen, Kristina Jørkov; Murray, Andrew Sean; Calligaro, Morgane; Macaire, Jean-Jacques; Robert, Eric; Lorblanchet, Michel; Aubry, Thierry; Bayle, Grégory; Bréhéret, Jean-Gabriel; Camus, Hubert; Chareille, Pascal; Egels, Yves; Guillaud, Émilie (2023-06-21). "The earliest unambiguous Neanderthal engravings on cave walls: La Roche-Cotard, Loire Valley, France". PLOS ONE. 18 (6): e0286568. Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1886568M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0286568. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 10284424. PMID 37343032.

- ^ a b c Henshilwood, C.S.; et al. (2018). "An abstract drawing from the 73,000-year-old levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa" (PDF). Nature. 562 (7725): 115–118. Bibcode:2018Natur.562..115H. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0514-3. PMID 30209394. S2CID 52197496.

- ^ Frayer, David W.; Radovčić, Jakov; Sršen, Ankica Oros; Radovčić, Davorka (11 March 2015). "Evidence for Neandertal Jewelry: Modified White-Tailed Eagle Claws at Krapina". PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0119802. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019802R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119802. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4356571. PMID 25760648.

- ^ d'Errico, Francesco; Tsvelykh, Alexander (29 March 2017). "A decorated raven bone from the Zaskalnaya VI (Kolosovskaya) Neanderthal site, Crimea". PLOS ONE. 12 (3): e0173435. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1273435M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0173435. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5371307. PMID 28355292.

- ^ Koto, Koray (November 2, 2022). "The Origin of Art and the Early Examples of Paleolithic Art". ULUKAYIN English.

- ^ Feehly, Conor (6 July 2021). "Beautiful Bone Carving From 51,000 Years Ago Is Changing Our View of Neanderthals". ScienceAlert. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ Leder, Dirk; et al. (5 July 2021). "A 51,000-year-old engraved bone reveals Neanderthals' capacity for symbolic behaviour". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 594 (9): 1273–1282. doi:10.1038/s41559-021-01487-z. PMID 34226702. S2CID 235746596. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ Morley, Iain (2006). "Mousterian Musicianship? The Case of the Divje Babe I Bone". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 25 (4): 317–333. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.2006.00264.x. Retrieved May 30, 2024.

- ^ Diedrich, Cajus G. (April 1, 2015). "'Neanderthal bone flutes': simply products of Ice Age spotted hyena scavenging activities on cave bear cubs in European cave bear dens". Royal Society Open Science. 2 (4). doi:10.1098/rsos.140022. PMC 4448875. PMID 26064624.

- ^ Watts, Ian (2009) Red ochre, body painting, and language: interpreting the Blombos ochre. In Botha, Rudolf P. & Knight, Chris (Eds.) The cradle of language. Oxford; New York, Oxford University Press.

- ^ Mackay, Alex; Welz, Aara (2008). "Engraved ochre from a Middle Stone Age context at Klein Kliphuis in the Western Cape of South Africa". Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (6): 1521–1532. Bibcode:2008JArSc..35.1521M. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.10.015.

- ^ Chazan, Michael; Horwitz, Liora Kolska (2009). "Milestones in the development of symbolic behaviour: a case study from Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa". World Archaeology. 41 (4): 521–539. doi:10.1080/00438240903374506. S2CID 4672735.

- ^ d'Errico, Francesco; García Moreno, Renata; Rifkin, Riaan F (2012). "Technological, elemental and colorimetric analysis of an engraved ochre fragment from the Middle Stone Age levels of Klasies River Cave 1, South Africa". Journal of Archaeological Science. 39 (4): 942–952. Bibcode:2012JArSc..39..942D. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.10.032.

- ^ Texier, Pierre-Jean; et al. (2010). "A Howiesons Poort tradition of engraving ostrich eggshell containers dated to 60,000 years ago at Diepkloof Rock Shelter, South Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (14): 6180–6185. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.6180T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913047107. PMC 2851956. PMID 20194764.

- ^ Texier, Pierre-Jean, et al. The context, form and significance of the MSA engraved ostrich eggshell collection from Diepkloof Rock Shelter, Western Cape, South Africa. Journal of Archaeological Science.

- ^ Lombard, M (2006). "Direct evidence for the use of ochre in the hafting technology of Middle Stone Age tools from Sibudu Cave". Southern African Humanities. 18: 57–67.; Lombard, M (2007). "The gripping nature of ochre: The association of ochre with Howiesons Poort adhesives and Later Stone Age mastics from South Africa". Journal of Human Evolution. 53 (4): 406–419. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.05.004. PMID 17643475.

- ^ Wadley, Lyn, Hodgskiss, Tamaryn & Grant, Michael (2009) Implications for complex cognition from the hafting of tools with compound adhesives in the Middle Stone Age, South Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- ^ Wadley, Lyn (2010). "Compound-Adhesive Manufacture as a Behavioral Proxy for Complex Cognition in the Middle Stone Age". Current Anthropology. 51: S111 – S119. doi:10.1086/649836. S2CID 56253913.

- ^ Rifkin, Riaan F. (2012) The symbolic and functional exploitation of ochre during the South African Middle Stone Age. Institute for Human Evolution (IHE). University of the Witwatersrand.

- ^ a b c Joordens, Josephine C. A.; d'Errico, Francesco; Wesselingh, Frank P.; Munro, Stephen; de Vos, John; Wallinga, Jakob; Ankjærgaard, Christina; Reimann, Tony; Wijbrans, Jan R.; Kuiper, Klaudia F.; Mücher, Herman J. (2015). "Homo erectus at Trinil on Java used shells for tool production and engraving". Nature. 518 (7538): 228–231. Bibcode:2015Natur.518..228J. doi:10.1038/nature13962. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 25470048. S2CID 4461751.

- ^ Chase, Philip G (2005). The Emergence of Culture: The Evolution of a Uniquely Human Way of Life. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-0-387-30512-7., pp. 145-146

KSF

KSF