Arts in the Philippines

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 58 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 58 min

This article contains too many images for its overall length. (January 2022) |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

|

Philippines portal |

The arts in the Philippines reflect a range of artistic influences on the country's culture, including indigenous art. Philippine art consists of two branches: traditional[1] and non-traditional art.[2] Each branch is divided into categories and subcategories.

Overview

[edit]The National Commission for Culture and the Arts, the cultural agency of the Philippine government, has categorized Filipino arts as traditional and non-traditional. Each category has sub-categories.

- Traditional arts:[1]

- Ethnomedicine – including the arts of hilot and the arts of the albularyo and babaylans[3]

- Folk architecture – including stilt, land, and aerial houses.

- Maritime transport – boat houses, boat-making, and maritime traditions.

- Weaving – including back-strap loom weaving and other, related forms of weaving.

- Carving – including woodcarving and folk non-clay sculpture.

- Folk performing arts – including dances, plays, and dramas.

- Folk (oral) literature – including epics, songs, and myths.

- Folk graphic and plastic arts – including calligraphy, tattooing, writing, drawing, and painting

- Ornaments – including mask-making, accessory-making, ornamental metal crafts

- Textile (fiber) art – including headgear weaving, basketry, and fishing gear

- Pottery – including ceramics, clay pots and sculpture

- Other artistic expressions of traditional culture – including non-ornamental metal crafts, martial arts, supernatural healing arts, medicinal arts, and constellation traditions

- Non-traditional arts:[2]

- Dance – including choreography, direction, and performance

- Music – including composition, direction, and performance

- Theater – including direction, performance, production design, lighting and sound design, and playwriting

- Visual arts – including painting, non-folk sculpture, printmaking, photography, installation art, mixed-media works, illustration, graphic arts, performance art, and imaging

- Literature – including poetry, fiction, essays, and literary or art criticism

- Film and broadcast arts – including direction, writing, production design, cinematography, editing, animation, performance, and new media

- Architecture and allied arts – including non-folk architecture, interior design, landscape architecture, and urban design

- Design – including industrial and fashion design

-

Madonna with Child, ivory statue with silver; unknown 17th-century artist

-

Singkil, a dance based on the Darangen (an Intangible Cultural Heritage and a National Cultural Treasure)

Traditional arts

[edit]Traditional arts in the Philippines include folk architecture, maritime transport, weaving, carving, folk performing arts, folk (oral) literature, folk graphic and plastic arts, ornaments, textile or fiber art, pottery, and other artistic expressions of traditional culture.[1] Traditional artists or groups of artists receive the National Living Treasures Award (Gawad Manlilikha ng Bayan Award (GAMABA)) for their contributions to the country's intangible cultural heritage.

Ethnomedicine

[edit]

Ethnomedicine is one of the oldest traditional arts in the Philippines. Traditions (and objects associated with them) are performed by medical artisans and shamans. Practices, grounded on the physical elements, are an ancient science and art. Herbal remedies, complementing mental, emotional, and spiritual techniques, are also part of many traditions as well. The category was added to the GAMABA in 2020.[3]

Folk architecture

[edit]Folk architecture in the Philippines varies by ethnic group, and structures are made of bamboo, wood, rock, coral, rattan, grass, and other materials. They include the hut-style bahay kubo, highland houses (known as bale) with four to eight sides, the coral houses of Batanes which protect from the area's harsh, sandy winds, the royal torogan (engraved with an intricate okir motif) and palaces such as the Darul Jambangan (Palace of Flowers), the residence of the sultan of Sulu before colonization. Folk architecture also includes religious buildings, generally called spirit houses, which are shrines to protective spirits or gods.[4][5][6] Most are open-air, house-like buildings made of native materials.[7][4] Some were originally pagoda-like (a style continued by natives who converted to Islam), and are now rare.[8] Other buildings have indigenous and Hispanic motifs (bahay na bato architecture and its prototypes). Many bahay na bato buildings are in Vigan, a World Heritage Site.[9] Folk structures range from simple, sacred stick stands to indigenous castles or fortresses (such as Batanes' ijangs and geological alterations such as the Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras (another World Heritage Site).[10][11][12][13]

-

Painting of shamanhood and ethnomedicine, including rituals

-

Some bahay na bato houses

-

Dakay house, the oldest surviving coral houses in the Batanes still used today (c. 1887)

-

Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras, World Heritage Site and a National Cultural Treasure

-

Batad Rice Terraces

Maritime transport

[edit]Maritime transport includes boat houses, boat-making, and maritime traditions. These structures, traditionally made of wood chosen by elders and crafters, connected the islands. Although boats are believed to have been used in the archipelago for thousands of years, the earliest evidence of boat-making has been carbon-dated to 689 AD: the Butuan boats identified as large balangays.[14][15][16] In addition to the balangay, indigenous boats include the two-masted double-outrigger fishing armadahan,[17][18] the avang trading ship,[19] the awang dugout canoes,[20] the balación sailing outrigger boat,[21] the bangka,[22] the bangka anak-anak canoe,[23] the salambáw-lifting basnigan,[24] the bigiw double-outrigger sailboat,[25] the birau dugout canoe,[23] the buggoh dugout canoe,[23] the casco barge,[26] the single mast and pointed chinarem,[19] the rough-sea open-deck chinedkeran,[19] the djenging double-outrigger plank boat,[23] the garay pirate ship,[27] the guilalo sailing outrigger ship,[28] the falua open-deck boat,[19] the junkun canoe,[23] the motorized junkung,[29] the outrigger karakoa and lanong warships,[30][31] the lepa houseboat,[32] the ontang raft,[23] the owong lake canoe,[33] the open-deck fishing boat panineman,[19] the double-outrigger paraw sailboat,[34] the salisipan war canoe,[35] the tataya fishing boat,[19] the motorized tempel, the dinghy tiririt,[36] and the outrigger vinta.[37] From 1565 to 1815, Manila galleons were built by Filipino artisans.[38]

-

A large karakoa outrigger warship, 1711

-

A balangay reconstruction

-

The Sama-Bajau's lepa house-boat with elaborate carvings

-

A large lanong outrigger warship, 1890

-

Filipino boat-builders in a Cavite shipyard (1899)

-

Garay warships of the Banguingui

-

An armadahan at Laguna de Bay (1968)

-

War canoe salisipan, 1890

-

Painting of a balación, 1847

-

Some of the remains of the Butuan Balangay (689-988 AD), a National Cultural Treasure

-

A Manila galleon visiting Micronesia, c. 1590s

-

A casco, 1906

Weaving

[edit]Weaving is an ancient art form, and each ethnic group has a distinct weaving technique.[39] The weaving arts include basket weaving, back-strap loom weaving, headgear weaving, and fishnet weaving.

Cloth and mat weaving

[edit]

Valuable textiles are made with a back strap loom.[40] Fibers such as cotton, abaca, banana fiber, grass, and palm are used in Filipino weaving.[41] There are a number of types of woven cloth. Pinilian is an Ilocano cotton cloth woven with a pangablan, using binakul, binetwagan, or tinumballitan styles. Bontoc weave emphasizes the concept of centeredness, key to the culture of the Bontoc people. The weave begins with the sides (langkit), followed by the pa-ikid (side panels), fatawil (warp bands), and shukyong (arrows). The sinamaki weaving then begins, incorporating a tinagtakho (human figure), minatmata (diamond), and tinitiko (zigzag). The last is the center (pa-khawa), with the kan-ay (supplementary weft). Kalinga textiles contain geometric designs; one motif is a lozenge pattern known as inata-ata. Piña is considered the finest indigenous Filipino textile. Aklanon textiles are used in national costumes. Hablon is the textile of the Karay-a and Hiligaynon peoples. Tapestry woven by the Yakan people uses the bunga-sama supplementary weft weave, the siniluan warp-floating pattern, the inalaman supplementary-weft technique, and the pinantupan weft-band pattern. Blaan weaving depicts crocodiles and curls. The Mandaya use a mud-dye technique. Meranaw textiles are used for the malong and other Maranao clothing. T'nalak is a Tboli textile.[42] The oldest known ikat textile in Southeast Asia is the Banton cloth, dating to the 13th to 14th centuries.[43]

Unlike cloth weaving with a loom, mats are woven by hand. They are woven in cool shade, and are kept cool to preserve their integrity. An example is the banig of Basey, where its weavers usually work in a cave. Fibers include banana, grass, and palm.[44]

-

Panel made of silk, piña, and metallic threads (1800s)

-

Northern Luzon textile used in skirt

Basketry

[edit]Baskets have intricate designs, styles and forms for specific purposes, such as harvesting, rice storage, traveling, and sword storage. Basket weaving is believed to have arrived with north-to-south human migration. Some of the finest baskets made are from Palawan, in the southwest. Materials vary by ethnic group, and include bamboo, rattan, pandan, cotton tassels, beeswax, abacá, bark, and dyes. Basketry patterns include closed crossed-over underweave, closed bamboo double-twill weave, and a spaced rattan pentagon pattern. Products include the tupil (lunch box), bukug (basket), kabil (carrying basket), uppig (lunch basket), tagga-i (rice basket), bay'ung (basket pouch), lig-o (winnowing tray), and binga (bag).[45][46] Weaving traditions have been influenced by modern demands.[47]

Woven headpieces are common, and cultures use a variety of fibers to create headgear such as the Ivatan vakul and the snake headpiece of the Bontoc.[48] Woven fish traps are a specialty of the Ilocano people.[49] Broom weaving is another tradition, exemplified by the Kalinga people.[50]

-

Various rice baskets

-

Filipino tobacco basket

-

Pasiking or basket bags

-

Ivatan woman wearing a vakul

-

T'boli women utilizing the s'laong kinibang in dance

-

Weaved hornbill headgear of the Ilongot

-

Gaddang people's weaved headgear

-

Filipino weaved hats

-

Ilocano merchants wearing the headgear kattukong and raincoat annangá

-

Ifugao brooms

-

Manila fishermen utilizing the sarambaw fishnet (c. 1800s)

-

Various weaved fish gears

-

Filipino cap

-

Variant of a Bontoc hat

-

Basket crafts made by the Iraya Mangyan

Relics

[edit]The Philippines has Buddhist artifacts[51][52] with Vajrayāna influence,[53][54][better source needed][55] most of which date to the ninth century and reflect the iconography of the Śrīvijayan empire. They were produced from the Agusan-Surigao area on Mindanao to Cebu, Palawan, and Luzon.

The Agusan image is a 2 kg (4.4 lb), 21-karat gold statuette found in 1917 on the Wawa River near Esperanza, Agusan del Sur, Mindanao,[56] dates to the ninth or tenth centuries. The image is commonly known as the Golden Tara, an allusion to its reported[57] identity as an image of a Buddhist Tara. The figure, about 178 mm (7.0 in)[58] tall, is of a female Hindu or Buddhist deity sitting cross-legged and wearing a headdress and other ornaments. It is on display in the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.[58][59][60] A bronze statue of Lokesvara was found in Isla Puting Bato in Tondo, Manila.[61]

An image of the Buddha was moulded on a clay medallion in bas-relief in the municipality of Calatagan. It reportedly resembles iconographic depictions of the Buddha in Siam, India, and Nepal: in a tribhanga[62] pose inside an oval nimbus. Scholars have noted a Mahayanic orientation in the image, since the boddhisattva Avalokiteśvara is also shown.[63]

Another gold artifact, from the Tabon Caves in the island of Palawan, is an image of Garuda, the bird who is the mount of Vishnu. The Hindu imagery and gold artifacts in the caves has been linked to those in Oc Eo, in the Mekong Delta of southern Vietnam. Crude bronze statues of the Hindu deity Ganesha were found by Henry Otley Beyer in 1921 in Puerto Princesa, Palawan, and in Mactan, Cebu. The statues were produced locally.[61] A bronze statue of Avalokiteśvara was also excavated that year by Beyer in Mactan.[61] A gold Kinnara was found in Surigao. Other gold relics include rings (some with images of Nandi), jewellery chains, inscribed gold sheets, and gold plaques with repoussé images of Hindu deities.[64][65]

Carving

[edit]Carving includes on woodcarving and the creation of folk non-clay sculptures.[66][67]

Woodcarving

[edit]Indigenous woodcarving by some ethnic groups dates to before the Hispanic arrival; the oldest may be fragments of a wooden boat dating to 320 AD.[68] A variety of woods are used to make wood crafts, which include bululs.[69][70] These wooden figures, known by a number of names, are found from north Luzon to southern Mindanao.[71] Wood okir is crafted by ethnic groups in Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago.[72][73] Wood crafts of objects such as sword hilts and musical instruments depict ancient, mythical beings.[74][75] Indigenous wood-crafting techniques have been utilized in Hispanic woodcarvings after colonization, such as in Paete.[76][77]

Religious Hispanic woodcarvings were introduced with Christianity, and are a fusion of indigenous and Hispanic styles. Paete is a center of religious Hispanic woodcarving.[76] Such woodcarving also exists in many municipalities, where most crafts depict the life of Jesus and the Virgin Mary.[78]

-

Kampilan hilts

-

Spinning wheel

-

San Agustin Church door carvings (1607), part of a World Heritage Site and a National Cultural Treasure

-

Carved saddle panel of the Yakan people, inlaid with shells

-

Carved bas relief at San Agustin Church, Manila

-

Ifugao rice spoon guarded by a wooden figure

-

Bulul god with pamahan cup (15th century)

-

Carved sarimanok

-

Wooden chest with bones

-

Carved holder for an agong

-

Tboli carving of a macaque and a turtle at Lake Sebu's museum

-

Carving depicting a Filipino farmer and a carabao

-

Tomb markers from the Sulu archipelago

-

Various crafts made with okir

-

Wooden Madonna

-

Giant wooden drums

-

A number of wooden shields

Stone, ivory, and other carvings

[edit]Stone carving predates Western colonization.[79] Carvings may represent an ancestor or a deity who helps the spirit of a loved one enter the afterlife.[80] Ancient carved burial urns have been found in many areas, notably in the Cotabato region.[81] The Limestone tombs of Kamhantik, in Quezon province, are thought to initially have rock covers and were sarcophagi. They are believed to have been originally roofed, as evidenced by holes where beams have been placed.[82] Stone grave marks are carved with okir motifs to aid the dead.[83] Mountainsides are carved to form burial caves, especially in the highlands of northern Luzon; the Kabayan Mummies are an example.[84] Marble carvings are centered in Romblon, and most (primarily Buddhist statues and related works) are exported.[85] With the arrival of Christianity, stone carvings became widespread; most are church facades or statues, or statues and other crafts for personal altars.[86] A notable stone carving is the facade of Miagao Church.[87]

Ivory carving has been practiced in the Philippines for a millennium; its oldest known ivory artifact is the Butuan Ivory Seal, dated to the ninth to 12th centuries.[88] Ivory religious carvings (locally known as garing) became widespread after ivory was imported to the Philippines from Asia, where carvings focused on Christian themes such as the Madonna and child, the Christ child, and the Sorrowful Mother.[89] Many of the ivory carvings from the Philippines have gold and silver designs.[89] The Filipino ivory trade has boomed because of the demand for carvings,[90] but the government has cracked down on the illegal trade. In 2013, the Philippines was the first country to destroy its ivory stock; the ivory trade has decimated the world's elephant and rhinoceros populations.[91] Horns of dead carabaos have substituted for ivory in the country for centuries.[92]

-

Stone carvings at the facade of Miagao Church, World Heritage Site and a National Cultural Treasure

-

Various ancient carved limestone burial urns

-

Bas relief at Panay Church (1770s)

-

Carved marbles from Romblon

-

Virgin Mary ivory head with inlaid glass eyes (18-19th century)

-

Visayan tenegre buffalo horn hilt

-

Ivory carving of Christ Child with gold paint (1580–1640)

-

Stamp of the Butuan Ivory Seal (9th-12th century)

-

Our Lady of La Naval de Manila, the oldest Christian statue in the Philippines made of ivory (1593 or 1596)

-

An ivory triptych (17th century)

-

Mother-of-pearl relief (19th century)

-

One of the carvings at the Basilica del Santo Niño

-

Teeth filing is present in some ethnic groups in the country

-

A likha portraying a god, one of only two likha that survived Spanish persecution and destruction

-

Moro helmet, exterior made of carved carabao horn (18th century)

Folk performing arts

[edit]Folk dances, plays, and dramas are performed. Each ethnic group has its own heritage, and Filipino folk performing arts also have Spanish and American influences. Some dances are related to those in neighboring Austronesian and other Asian countries.[93] Folk performing arts include the banga, manmanok, ragragsakan, tarektek, uyaoy (or uyauy),[94] pangalay, asik, singkil, sagayan, kapa malong malong,[95] binaylan, sugod uno, dugso, kinugsik kugsik, siring, pagdiwata, maglalatik, tinikling, subli, cariñosa, kuratsa, and pandanggo sa ilaw.[96][97][98][99] Folk dramas and plays are based on popular epics such as Hinilawod,[100] and the Senakulo is a popular drama with Hispanic groups.[101][102]

-

Singkil royal dance

-

Senakulo in Bulacan

-

Lumad courtship dance

Folk (oral) literature

[edit]Folk (oral) literature includes the epics, songs, myths, and other oral literature of Filipino ethnic groups. The country's poetry is rich in metaphors.[103] Tanaga poetry has a 7777 syllable count, and its rhyme forms range from dual rhymes to none.[103] Awit poetry has 12-syllable quatrains, with rhyming similar to the Pasyon[104][105] chanted in the pabasa.[106] Another awit is the 1838 Florante at Laura.[107] Dalit poetry contains four lines of eight syllables each.[108] Ambahan poetry consists of seven-syllable lines with rhythmic end syllables, often chanted and sometimes written on bamboo.[109] Balagtasan is a debate in verse.[110] Other poems include A la juventud filipina,[111] and Ako'y may alaga.[112][113]

Epic poems include the 17-cycle, 72,000-line Darangen of the Maranao[114] and the Hinilawod.[115] Others include Biag ni Lam-Ang, Ibalon, Hudhud, Alim, the Ulalim cycle, Lumalindaw, Kudaman, the Agyu Cycle, Tulelangan, Gumao of Dumalinao, Ag Tubig Nog Keboklagan, Keg Sumba Neg Sandayo, and Tudbulul.[116] Filipino Sign Language is used to pass on oral literature to the hearing-impaired.[117] Folk literature is documented by scholars in manuscripts, tapes, and video recordings.[118][119]

-

Bakunawa, a deity from the Visayas and Bicol, in a divination-rotation chart as explained in Signosan (1919)

-

A manananggal drawing, as depicted in folk stories

-

A buraq sculpture, as depicted in folk stories

-

Sculpture depicting Makiling, the protector-goddess of Mount Makiling

-

A hogang, fern-trunk statue, of a god protecting boundaries in Ifugao

-

Performance at the Kaamulan, depicting gods and heroes from the people's ancient religions

Folk graphic and plastic arts

[edit]These are tattooing, folk writing, and folk drawing and painting.

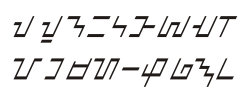

Folk writing (calligraphy)

[edit]The Philippines has a number of indigenous scripts collectively known as suyat, each of which has its own calligraphy. Since 16th-century Spanish colonization, ethnolinguistic groups have used the scripts in a variety of media. By the end of the colonial era, only four suyat scripts survived and continue to be used: the Hanunó'o and Buhid scripts and those of the Tagbanwa and Palawan peoples. All four were inscribed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Programme as Philippine Paleographs (Hanunoo, Buid, Tagbanua and Pala’wan) in 1999.[120]

Artists and cultural experts have also revived extinct suyat scripts, including the Visayan badlit script, the iniskaya script of the Eskaya people, the baybayin script of the Tagalog people, the sambali script of the Sambal people, the basahan script of the Bicolano people, the sulat pangasinan script of the Pangasinense people, and the kur-itan (or kurdita) script of the Ilocano people.[121][122][123][124][125] Spanish[126] and Arabic Jawi scripts are also used.[127][128] Suyat-based calligraphy has become increasingly popular.[129][130] Philippine Braille is used by the visually impaired.[131]

-

Amami, a fragment of a prayer written in kur-itan or kurdita, the first to use the krus-kudlit

-

Laguna Copperplate Inscription written in the kawi script, precursor to baybayin (900 CE), a National Cultural Treasure

-

Basahan (surat bikol) script sample

-

Hanunó'o calligraphy written on bamboo

-

Buhid script sample

-

Jawi script, used in the Sulu archipelago

-

The Koran of Bayang, written in the kirim script on paper, a National Cultural Treasure; kirim is used in mainland Muslim Mindanao

-

Eskaya script sample

-

Pages of the Doctrina Christiana, an early Christian book in Spanish, Tagalog in Latin script and in Baybayin (1593)

-

Indigenous script in the country's passport

-

Tagbanwa calligraphy on bamboo

Folk drawing and painting

[edit]Folk drawing has been known for thousands of years. The oldest folk drawings are rock drawings and engravings which include the Angono Petroglyphs in Rizal, created during the Neolithic (6000 to 2000 BC). The drawings have been interpreted as religious, with infant drawings to relieve sickness in children.[132] Another petroglyph is in Alab (Bontoc), dated as not later than 1500 BC and containing fertility symbols such as the pudenda. Ancient petrographs are also found; those in Peñablanca and Singnapan are drawn with charcoal, and those in Anda (Bohol) are drawn with red hematite.[133] Recently discovered petrographs in Monreal (Ticao) include drawings of monkeys, human faces, worms (or snakes), plants, dragonflies, and birds.[134]

Evidence indicates that indigenous Filipinos have been painting and glazing pottery for thousands of years. Pigments used for painting range from gold, yellow, reddish-purple, green, white, and blue-green to blue.[135] Statues and other creations have also been painted with a variety of colors. Painting on skin is practiced, especially by the Yakan people.[136]

Tattooing was introduced by the Austronesian peoples thousands of years ago, and it developed into cultural symbols in a number of ethnic groups.[137][138][139] It was first documented the 16th century, with the bravest Pintados (people of central and eastern Visayas) the most tattooed. Similar tattooed peoples were the Bicolanos of Camarines and the Tagalogs of Marinduque.[140][141][142] Tattooed people in Mindanao include the Manobo, whose tattoo tradition is known as pang-o-túb.[143][144] The T'boli also tattoo their skin in the belief that the tattoos glow after death, guiding the soul in its journey to the afterlife.[145] The best-known tattooed people may have been the Igorot people of highland Luzon. Only Tinglayan in Kalinga has traditional tattoo artists crafting batok; they were headed by master tattooist and Kalinga matriarch Whang-od.[146][147] Traditional tattooing has experienced a revival after centuries of decline.[148]

-

A portion of the Angono Petroglyphs (6000-2000 BC), a National Cultural Treasure

-

Filipino American dancers wearing traditional Yakan facial paintings called tanyak tanyak

-

Painting made with the Waray people's kut-kut technique, developed in Samar

-

Painted ivory statue of St. Joseph (17th century)

-

Pintados recorded in the Boxer Codex (c. 1590)

-

Whang-od applying a Kalinga tattoo

-

Tattooed Bontoc warrior

-

Aeta man with body scarification

Ornaments

[edit]Ornamental art includes glass art, accessories and metal crafts.[1]

Glass art

[edit]Glass art is found in places such as Pinagbayanan.[149] Stained glass has been a feature of many churches since Spanish colonization. European craftspeople initially produced stained glass, with Filipinos beginning to join the craft during the 20th century.[150] The Manila Cathedral contains a number of stained-glass windows.[151] [better source needed] Other glass art includes chandeliers and sculptures.[152]

-

Jeremiah at Aringay church

-

San Sebastian Church window, part of a National Cultural Treasure

-

Zadkiel at Samar church

-

Cultural Center of the Philippines chandelier

Hats, masks, and related arts

[edit]The gourd-based tabungaw of Abra and Ilocos Region is an example of hat-making.[153] Indigenous hats were widely worn until the 20th century (when they were replaced by Western styles), and are currently worn for festivals, rituals, or theatre.[48][154]

Mask-making is an indigenous and imported tradition; some communities made masks before colonization, and other mask-making traditions were introduced by trade with Asia and the West. These masks are primarily worn during the Moriones and MassKara Festivals.[155][156][157] Puppet-making is a related art whose products are used in plays and festivals such as the Higantes Festival.[158] Most indigenous masks are made of wood, and gold masks (made for the dead) were common in the Visayas region before Spanish colonization. Masks made of bamboo and paper, used in Lucban depict the typical Filipino farming family. Masks in Marinduque are used in pantomime; those in Bacolod depict egalitarian values, regardless of economic standards. Masks are worn in theatrical epics, especially those related to the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.[159]

-

Gourd-based Salakot (bottom)

-

Brass helmets (top) from Bangsamoro

-

Bontoc wood hat

-

Tortoiseshell salakot with inlaid silver

-

Mandaya people's sadok

-

Participant with headgear during the Ati-Atihan festival

-

Masked participants during the MassKara Festival

-

Various masks used during the Kwaresma

Accessories

[edit]Accessories are generally worn with clothing, and some are accessories for houses, altars, and other objects. Of the Philippines' over 100 ethnic groups, the most accessorized may be the Kalinga people.[160] The Gaddang people also use many accessories.[161] The best-known accessory is the lingling-o, a pendant or amulet used from Batanes in the north to Palawan in the south.[162][163] The oldest known lingling-o has been dated to 500 BC and is made of nephrite.[163] Shells have also traditionally been used for accessories.[164]

Gold is crafted by Filipino ethnic groups, and the country's best-known goldsmiths came from Butuan. Regalia, jewelry, ceremonial weapons, tooth ornamentation, and ritualistic and funerary objects made of high-quality gold have been found at a number of sites, and the archipelago's gold culture flourished between the tenth and thirteenth centuries. Some gold-crafting techniques were lost in colonization, but techniques influenced by other cultures have been adopted by Filipino goldsmiths.[165][166]

-

Accessory of the Gaddang people

-

A lingling-o of the Kalinga people

-

Ilongot earring

-

Filipino gold and coral necklace (17th-18th c.)

-

Gold jewelries (12th-15th century)

-

Itneg accessory

-

Ilongot hair ornament

-

Bontoc belt

-

Mother-of-pearl necklace

-

Ifugao pectoral accessory

-

Necklaces made of gold, semi-precious stones, and glass (12th-15th century)

-

Necklace made of gold and coral (17th–19th century)

Metal ornaments

[edit]Ornamental metal crafts are metal-based products used to beautify something else, metal or non-metal, and those made by the Maranao in Tugaya are valued. Metal crafts by the Moro people decorate a variety of objects, and are inscribed with the okir motif.[167] Metal crafts also decorate religious objects such as altars, Christian statues, and vestments. Apalit, in Pampanga, is a center of the craft.[168] Gold has been used in a number of ornaments, and most which survive are human accessories with elaborate, ancient designs.[165]

-

Our Lady of Manaoag with metal headpiece, part of a National Cultural Treasure

-

Golden garuda ornament from Palawan

-

Santa Monica Church chandelier, part of a National Cultural Treasure

-

Indigenous armor from Sulu, made of metal, carabao horn, and silver

-

Wrought iron at Malolos Church

-

Northern Luzon metal belt

Pottery (ceramic) arts

[edit]Pottery (ceramics, clay, and folk clay sculpture) has been part of Filipino culture for about 3,500 years.[169] Notable artifacts include the Manunggul Jar (890–710 BCE)[170] and Maitum anthropomorphic pottery (5 BC-225 AD).[171] High-fired pottery was first made around 1,000 years ago, leading to a ceramic age in the Philippines.[135] Ceramics were traded, and pottery and fragments from the Arab world (possibly Egypt) and East Asia have been found.[135] Specific jars were also traded directly to Japan.[172] Before colonization during the 16th century, foreign porcelain was popular in a number of communities; according to oral tradition from Cebu, indigenous porcelain was produced at the time of Cebu's early rulers.[173] The earliest known indigenous porcelain has been dated to the 1900s, however; porcelain found at Filipino archaeological sites was labeled "imported", which has become a subject of controversy. Filipinos worked as porcelain artisans in Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, re-introducing the craft in the Philippines. All but one porcelain artifact from the era survived World War II.[174] Notable folk clay art includes The Triumph of Science over Death (1890)[175] and Mother's Revenge (1894),[176] and popular pottery includes the tapayan and palayok. Pottery-making has received recent media attention.[177][178]

-

Philippine ceramic (100-1400 CE)

-

Calatagan Pot with suyat calligraphy (14th-15th century)

-

Burial pots, with the right having wave designs

-

The Intramuros Pot Shard, with a script on it

-

Burial jar top of one of the Maitum anthropomorphic pottery from Sarangani (5 BC-370 AD)

-

Maitum Anthropomorphic Burial Jar No. 13 (5 BC-370 AD), a National Cultural Treasure

-

The Mother's Revenge (1894), a National Cultural Treasure

-

Multiple clay heads used as toppings for burial jars, each with a unique face

-

An ancient mini-jar and a goblet

-

An ancient burial jar head

-

Porcelain found in the Philippines

-

Porcelain jar found in the Philippines (11th century)

-

Porcelain found in Palawan (15th century)

-

Porcelain found in the Philippines (11th-12th century)

Other traditional arts

[edit]Other traditional arts, including non-ornamental metal crafts, martial arts, supernatural healing arts, medicinal arts, and constellation traditions, cannot be specifically categorized.

Non-ornamental metal crafts

[edit]Non-ornamental metal crafts are metal products with simple, utilitarian designs. The Moro people are known for their metalwork, which is usually decorated with the okir motif.[179] Baguio is also a center for metalwork.[180] Hispanic metal crafts are common in the lowlands. They include large bells, and Asia's largest bell is at Panay Church.[181] Metal deities, notably of gold, are also found.[165][182]

-

Brass gadur

-

Lantaka guns

-

Copper betel nut box with silver inlay

-

Ewer from Mindanao (1800)

-

Detail of a lantaka gun

-

Silver ciborium

-

The largest church bell in Asia, housed at Panay Church, a National Cultural Treasure

-

Manobo jewel case

-

Bronze jars (19th century)

-

Hinged brass box (1800)

-

Gangsa gongs of the Kalinga people

-

Kulintang gongs of the Maranao people

Sword making

[edit]Filipino bladesmiths have been creating swords and other bladed weapons for centuries. Many swords are made for ceremonies and agriculture, and others are used for warfare. The best-known Filipino sword is the kampilan, a sharp blade with a spikelet one the flat side of the tip and a pommel depicting one of four sacred creatures: a bakunawa (dragon), a buaya (crocodile), a kalaw (hornbill), or a kakatua (cockatoo).[183] Other Filipino bladed weapons include the balarao, balasiong, balisong, balisword, bangkung, banyal, barong, batangas, bolo, dahong palay, gunong, gayang, golok, kalis, karambit, panabas, pinutí, pirah, gunong, susuwat, tagan, and utak. A variety of spears (sibat), axes, darts (bagakay), and arrows (pana or busog) are also used.[184]

-

Kampilan sword from Sulu

-

Basih weapons

-

Yakan ceremonial swords

-

Lumad swords from Mindanao and Igorot axes from Luzon

-

Kalis sword from Sulu

-

Moro swords

-

War, ceremonial, and fishing spears in the Philippines

-

Lumad daggers in Mindanao

-

Swords from Luzon and Visayas

-

Various balisongs

-

Various swords from the Visayas

Martial arts

[edit]Filipino martial arts vary by ethnic group. The best-known is arnis (also known as kali and eskrima) (the country's national sport and martial art), which has weapon-based fighting styles with sticks, knives, bladed and improvised weapons and open-hand techniques. Arnis has changed over time, and was also known as estoque, estocada, and garrote during Spanish colonization. The Spanish recorded it as called paccalicali-t by the Ibanags, didya (or kabaroan) by the Ilocanos, sitbatan or kalirongan by the Pangasinenses, sinawali ("to weave") by the Kapampangans, calis or pananandata ("use of weapons") by the Tagalogs, pagaradman by the Ilonggos, and kaliradman by the Cebuanos.[185]

Unarmed martial-arts techniques include pangamot (the Bisaya), suntukan (the Tagalogs), sikaran (the Rizal Tagalogs), dumog (the Karay-a), buno (the Igorot people), and yaw-yan. Martial-arts weapons include the baston (or olisi), bangkaw (or tongat), dulo-dulo, and tameng. Edged weapons include the daga (or cuchillo), gunong, punyal and barung (or barong), balisong, karambit (with blades resembling tiger claws), espada, kampilan, ginunting, pinuti, talibong, itak, kalis, kris, golok, sibat, sundang, lagaraw, ginunting, and pinunting. Flexible weapons include latigo, buntot pagi, lubid, sarong, cadena (or tanikala), and tabak-toyok. Projectile weapons include the pana, sibat, sumpit, bagakay, tirador (or pintik or saltik), kana, lantaka, and luthang.[186][187][188] Related martial arts include kuntaw and silat.[189][full citation needed][190][page needed][191]

-

Kalasag, shields used in Filipino warfare

-

Arnis being taught in Australia

-

Sambal warriors specializing in archery and falconry, recorded in the Boxer Codex

-

Suntukan sequence

-

Kuntaw utilized in dance

-

Statue depicting the sikaran

-

Jendo[192]

Cuisine

[edit]Filipino cuisine encompasses the country's more than 100 ethnolinguistic groups. Most mainstream dishes are from the Bikol, Chavacano, Hiligaynon, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Maranao, Pangasinan, Cebuano (or Bisaya), Tagalog, and Waray groups. The style of cooking and the associated foods have evolved over centuries from their Austronesian origins to a mixed cuisine with Indian, Chinese, Spanish, and American influences.[193] Dishes range the simple, such as fried salted fish and rice, to complex paellas and cocidos for Spanish fiestas. Popular dishes include lechón[194] (whole roasted pig), longganisa (Philippine sausage), tapa (cured beef), torta (omelette), adobo (chicken or pork braised in garlic, vinegar, oil and soy sauce, or cooked until dry), kaldereta (meat stewed in tomato sauce), mechado (fatty beef in a soy-tomato sauce), puchero (beef in a banana-and-tomato sauce), afritada (chicken or pork simmered in tomato sauce with vegetables), kare-kare (oxtail and vegetables cooked in peanut sauce), pinakbet (kabocha squash, eggplant, beans, okra, and tomato stew flavored with shrimp paste), crispy pata (deep-fried pig's leg), hamonado (pork sweetened in pineapple sauce), sinigang (meat or seafood in a sour broth), pancit (noodles), and lumpia (fresh or fried spring rolls).[195]

-

Sisig, usually served in scorching metal plates

-

Bibingka, a popular Christmas rice cake with salted egg and grated coconut toppings

-

Halo-halo, a common Filipino dessert or summer snack

-

Chicken adobo on rice

-

Sinigang, a sour soup with meat and vegetables

-

Lechon, whole roasted pig, stuffed with spices

Others

[edit]Shell crafts are common, due to the variety of mollusk shells available. The country's shell industry emphasizes crafts made of capiz shells, which are seen in a variety of products including capiz-shell windows, statues, and lamps.[164] Lantern-making is also a traditional art form which began after the introduction of Christianity, and many lanterns (locally known as parol) are in Filipino streets and in front of houses for the Christmas season (which begins in September and ends in January, the world's longest Christmas season). The Giant Lantern Festival, which also celebrates Christmas, features large lanterns made by Filipino artisans.[196] Pyrotechnics are popular during the New Year celebrations and the Christmas season. The Philippines has hosted the Philippine International Pyromusical Competition, the world's largest pyrotechnic competition (previously known as the World Pyro Olympics) since 2010.[197]

Lacquerware is a less-common art form. Filipino researchers are studying the possibility of turning coconut oil into lacquer.[198][199][200] Paper arts are common in many communities; examples include the taka papier-mâché of Laguna and the pabalat of Bulacan.[201] A form of leaf-folding art is puni, which uses palm leaves to create forms such as birds and insects.[201]

Bamboo art is also common, with products including kitchen utensils, toys, furniture, and musical instruments such as the Las Piñas Bamboo Organ (the world's only organ made of bamboo).[202] In bulakaykay, bamboo is bristled to create large arches.[201] Floristry is popular for festivals, birthdays, and Undas.[203] Leaf speech (language and meaning) is popular among the Dumagat people, who use leaves to express themselves and send secret messages.[204]

Shamanism and its related healing arts are found throughout the country, with each ethnic group having its unique concepts of shamanism and healing. Philippine shamans are regarded as sacred by their ethnic groups. The introduction of Abrahamic religions (Islam and Christianity) suppressed many shamanitic traditions, with Spanish and American colonizers demeaning native beliefs during the colonial era. Shamans and their practices continue in some parts of the Philippines.[205] The art of constellation and cosmic reading and interpretation is a fundamental tradition among all Filipino ethnic groups, and the stars are used to interpret for communities to conduct farming, fishing, festivities, and other important activities. Notable constellations include Balatik and Moroporo.[206] Another cosmic reading is the utilization of earthly monuments, such as the Gueday stone calendar of Besao, which locals use to see the arrival of kasilapet (the end of the current agricultural season and the beginning of the next one).[207]

-

View from a Capiz-shell window

-

Typical shell lamp in the Philippines

-

A huge lantern during the Giant Lantern Festival

-

Traditional bamboo and paper lanterns, sometimes made with bamboo and capiz shells as well

-

Traditional leaf lantern

-

Taka, a type of papier-mâché art in Laguna

-

One form of sampaguita garland-making

Non-traditional arts

[edit]Non-traditional arts include dance, music, theater, visual arts, literature, film and broadcast arts, architecture and allied arts, and design.[2] A distinguished artist is inducted as a National Artist of the Philippines.

Dance

[edit]Dance in the Philippines includes choreography, direction, and performance. Philippine dance is influenced by the country's folk performing arts and its Hispanic traditions; a number of styles also have global influences. Igorot dances such as banga,[94] Moro dances such as pangalay and singkil,[95] Lumad dances such as kuntaw, kadal taho and lawin-lawin, and Hispanic dances such as maglalatik and subli have been incorporated into contemporary Filipino dance.[96][97][98][99] Ballet has been popular since the early 20th century.[208] Pinoy hip hop music has influenced dances, a number of which have adopted global standards of hip hop and break dances.[209] Filipinos choreograph traditional and Westernized dances, with some companies focusing on Hispanic and traditional dance.[210][211]

-

Dancers during the Sinulog Festival

-

Filipinos performing Hispanic dances in an international stage

-

Dancers during the Pamulinawen

-

Performers of Moro dances in an international stage

Music

[edit]Musical composition, direction, and performance are central to non-traditional music. The basis of Filipino music is the heritage of the country's many ethnic groups, some of whom have been influenced by other Asian and Western music (primarily Hispanic and American). Philippine folk music includes the chanting of epic poems such as Darangen and Hudhud ni Aliguyon, and singing the Harana serenade. Musical genres include the Manila sound,[212] Pinoy reggae,[213] Pinoy rock,[214] Pinoy pop,[215] Tagonggo,[216] kapanirong,[217] kulintang,[218] kundiman,[219] bisrock,[220] and Pinoy hip hop.

-

Choir music

-

PUP Chorale

-

Depiction of harana

Theater

[edit]Theater has a long history, and includes direction, performance, production design, light and sound design, and playwriting are the focal arts. It is Austronesian in character, evidenced by ritual, mimetic dances. Spanish culture has influenced Filipino theater and drama: the komedya, sinakulo, playlets, and sarswela. Puppetry, such as carrillo, is another theater art.[221] Anglo-American theater has influenced bodabil. Modern, original plays by Filipinos have also influenced the country's theater.[222][223][224]

-

Promotion for the opera, Sangdugong Panaguinip (1902)

-

Tanghalang Pambansa (National Theater)

Visual arts

[edit]Visual arts include painting, sculpture, printmaking, photography, installation art, mixed-media works, illustration, graphic arts, performance art, and imaging.

Painting

[edit]Folk painting has always been part of Filipino culture.[133][225] Petroglyphs and petrographs, the earliest known folk drawings and paintings, originated during the Neolithic.[226] Human figures, frogs, lizards, and other designs were depicted. They may have been primarily symbolic, associated with healing and sympathetic magic.[227]

Other Asian and Western cultures influenced the art of painting. From the 16th century to the end of the colonial period, religious paintings were used to spread Catholicism. Most were part of churches, such as ceilings and walls. Non-religious paintings were also known.[228] Notable works include Nuestra Senora de la Soledad de Porta Vaga (1692)[229] and paintings at Camarin de da Virgen (1720).[230] Wealthy, educated Filipinos introduced secular art during the 19th century. The number of watercolour paintings increased, and subjects began to include landscapes, Filipino people and fashion, and government officials. Portraits included self-portraits, Filipino jewelry, and native furniture. Landscape paintings depicted ordinary Filipinos participating in daily life. The paintings, often ornately signed, were made on canvas, wood, and a variety of metals.[228] Watercolours were painted in the Tipos del País[231] or Letras y figuras style.[232]

Notable 19th-century oil paintings include Basi Revolt paintings, Sacred Art of the Parish Church of Santiago Apostol (1852), Spoliarium (1884), La Bulaqueña (1895), and The Parisian Life (1892).[230] A notable modern painting is The Progress of Medicine in the Philippines (1953).[230] After World War II, paintings were influenced by the effects of war. Common themes included battle scenes, destruction, and the suffering of the Filipino people.[233] Nationalistic themes included International Rice Research Institute (1962) and the Manila Mural (1968)[230] Twentieth- and 21st-century paintings have showcased native Filipino cultures as part of the spread of nationalism.[234] Notable paintings during the era include Chickens (1968)[235] and Sarimanok series (late 20th century).[236] Some works have criticized lingering colonial viewpoints such as discrimination against darker-skinned people and the negative effects of colonialism; examples are Filipina: A racial identity crisis (1990s)[237][238] and The Brown Man's Burden (2003).[239] A number of works have protested against state authoritarian rule, human-rights violations, and fascism.[240][241][242]

-

Basi Revolt (1807), a National Cultural Treasure

-

The Parisian Life (Interior d'un Cafi) (1892), a National Cultural Treasure

-

Painting utilizing the Letras y figuras technique (1847)

-

The Death of Cleopatra (1881)

-

Las Damas Romanas (1882)

-

Entrance of the Camarin de la Virgen (1720–1725), a National Cultural Treasure

-

Balilihan Church ceiling

-

Our Lady of the Rosary retablo

Sculpture

[edit]Sculpture is popular in the Philippines.[243] Notable sculptures include Oblation, the Rizal Monument to nationalist José Rizal,[244] the Tandang Sora National Shrine commemorating Melchora Aquino,[245] the Mactan Shrine to Lapulapu,[246] the People Power Monument,[247] Filipina Comfort Women,[248] and the Bonifacio Monument commemorating Andres Bonifacio.[249][250]

-

Mary and Child

-

Rizal Monument (1913), a National Cultural Treasure

-

Bonifacio Monument (1933), a National Cultural Treasure

-

Commonwealth statue

Other visual arts

[edit]Printmaking began in the Philippines after the country's religious orders – the Dominicans, Franciscans and Jesuits – began printing prayer books and inexpensive religious images (such as the Virgin Mary, Jesus Christ, or the saints) to spread Roman Catholicism. Maps were also printed, including the 1734 Velarde map. Printmaking has diversified to include woodblock printing and other forms.[251] Photography began during the 1840s, and photos were used during the colonial era as media for news, tourism, anthropology and other documentation, and as colonial propaganda.[252] After independence, photography became popular for personal and commercial use.[253]

-

Religious print used for colonialism in the Philippines, 1896

-

An original copy of the printed Velarde map, 1734

-

Leonor Rivera crayon sketch (19th century)

-

Malolos Congress photo (1898)

-

Pre-1863 lithograph photo of Malolos Cathedral

-

Third frame of the Filipino comic, The Monkey and The Turtle (1886)

New Art Form

[edit]The Kutbayin Movement is a fresh, original art form that reimagines Baybayin, the ancient Filipino script and Kutkut art, into a vibrant, modern medium of expression. Spearheaded by renowned Filipino-American artist Fred DeAsis, this movement is more than just art—it’s a celebration of our heritage, a reconnection to our roots, and a bold step toward shaping the future of Filipino culture.

Literature

[edit]Poetry, fiction, essays, and literary and art criticism are usually influenced by folk literature, which focuses on epics, ethnic mythology, and related stories and traditions. Calligraphy on a variety of media was used to create literary works; an example is Mangyan ambahan poetry.[254] Colonial literature focused first on Spanish-language works, and then English-language works. From 1593 to 1800, most literature in the Philippines consisted of Spanish-language religious works; examples are Doctrina Christiana (1593)[255] and a Tagalog rendition of the Pasyon (1704).[256] Colonial literature was also written in native languages, primarily religious and governmental works promoting colonialism.[252] Non-colonial Filipino literature was written by local authors as well; oral traditions were incorporated into works by Filipino writers, such as the 17th-century manuscript of the ancient Ilocano epic Biag ni Lam-ang.[257] Florante at Laura was published in 1869, combining fiction with Asian and European themes.[258][unreliable source?][259] In 1878[260] or 1894,[261] Ang Babai nga Huaran (the first modern play in any Philippine language) was written in Hiligaynon. Spanish literature evolved into a nationalist stage from 1883 to 1903; Nínay, the first novel written by a Filipino, was published at this time. Literature critical of colonial rulers was published, such as the 1887 Noli Me Tángere and the 1891 El filibusterismo.[262] The first novel in Cebuano, Maming, was published in 1900.[263] The golden age of Spanish-language literature was from 1903 to 1966, and works in native languages and English were also popular. Banaag at Sikat, a 1906 novel, explores socialism, capitalism, and organized labor.[264] The first Filipino book written in English, The Child of Sorrow, was published in 1921. Early English literature is characterized by melodrama, figurative language, and an emphasis on local color.[265] A later theme was the search for Filipino identity, reconciling Spanish and American influence with the Philippines' Asian heritage.[266] Portions of Sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag were published in 1966 and 1967, and were combined in a 1986 novel.[267] During the martial-law era, works such as Dekada '70 (1983)[268] and Luha ng Buwaya (1983) criticizing human-rights violations by those in power were published.[269][270] Twenty-first-century Filipino literature has explored history, global outlooks, equality, and nationalism. Major works include Smaller and Smaller Circles (2002),[271] Ladlad (2007),[272] Ilustrado (2008),[273] and Insurrecto (2018).[274]

-

Doctrina Christiana, 1593

-

Florante at Laura, originally published in 1869

-

Noli Me Tángere, 1887

-

El filibusterismo, 1891

Film and broadcast arts

[edit]The film and broadcast arts focus on direction, writing, production design, cinematography, editing, animation, performance, and new media. Filipino cinema began in 1897, with the introduction of moving pictures in Manila. Foreign filmmakers worked in the country until 1919, when filmmaker José Nepomuceno made the first Filipino film, Country Maiden.[275] Interest in film as art had begun by the 1930s, with theatre an important influence. Films made during the 1940s were realistic, due to the occupation years of World War II. More artistic, mature films were produced a decade later.[276][277] The 1960s were a decade of commercialism, fan movies, soft porn films, action films, and western spin-offs, leading to a golden age during the 1970s and 1980s under dictatorship. These films were overseen by the government, and a number of filmmakers were arrested. One notable film made at that time was Himala, which addressed religious fanaticism. The period after martial law dealt with more serious topics, and independent films were popular. The 1990s saw the emergence of Western-themed films and the continued popularity of films focusing on poverty; examples of the latter include Manila in the Claws of Light, The Flor Contemplacion Story, Oro, Plata, Mata, and Sa Pusod ng Dagat.[277] Twenty-first-century Filipino films have examined human equality, poverty, self-love, and history.[278] Notable films include The Blossoming of Maximo Oliveros,[279] Caregiver,[280] Kinatay,[281] Thy Womb,[282] That Thing Called Tadhana,[283] The Woman Who Left,[284] and the film version of the novel Smaller and Smaller Circles.[285]

-

A cinema inside a Filipino mall

-

A postcard for the film, Zamboanga (1936)

-

Various decaying old Filipino films. Restoration of some films have been undertaken by the ABS-CBN Film Restoration Project

-

Eden, a former cinema conserved as part of the Malolos Historic Town Center

Architecture and allied arts

[edit]Architecture focuses on non-folk architecture and its allied arts, such as interior design, landscape architecture, and urban design.

Architecture

[edit]Filipino architecture is influenced by the folk architecture of its ethnic groups, including the bahay kubo, bahay na bato, torogan, idjang, payyo, and shrines and mosques.[286] Western Baroque architecture was introduced by the Spanish during the 16th century; examples are the Manila Cathedral and Boljoon Church. It evolved into Earthquake Baroque, used to build Binondo Church, Daraga Church and the World Heritage Sites of Paoay Church, Miagao Church, San Agustin Church, and Santa Maria Church.[87][287][288] Throughout the colonial era, a variety of architectural styles were introduced; a Gothic Revival example is San Sebastian Church, Asia's only all-steel church. Beaux-Arts architecture became popular among the wealthy, and an example is the Lopez Heritage House.[286] Art Deco is popular in some Filipino communities, and the city of Sariaya is considered the country's Art Deco capital.[289] Italian and Italian-Spanish architecture is seen in Fort Santiago and the Ruins. An example of Stick-built construction is Silliman Hall. Many official buildings have neoclassical architecture; examples include the Baguio Cathedral, Manila Central Post Office, and the National Museum of Fine Arts. After independence, Brutalism was employed during the martial-law era. After the restoration of democracy, indigenous architecture revived during the late 20th and 21st centuries; these buildings have become bases for Filipino nationalism. Modern architecture is popular, and examples include Saint Andrew the Apostle Church and the Manila Hotel.[286] Culturally-important buildings have been demolished despite preservation laws, and cultural workers and architects are attempting to prevent further demolition.[290]

-

Gothic revival San Sebastian Church (c. 1891), a National Cultural Treasure

-

Art Deco Natalio Enriquez Ancestral House (c. 1931)

-

Neo-vernacular Cotabato City Hall (20th century)

-

Italian-style The Ruins (mansion) (c. 1990s)

-

Renaissance revival University of Santo Tomas Main Building (1927), a National Cultural Treasure

-

Baroque Dupax Church (1776), a National Cultural Treasure

-

Fortress-style Capul Church (1781), a National Cultural Treasure

-

Barn-style Jasaan Church (1887), a [National Cultural Treasure

-

Moorish-style Sulu Provincial Capitol building

-

Neo-vernacular Coconut Palace (1978)

-

Spanish-American Lizares Mansion (1937)

-

Neoclassical Manila Central Post Office (1928)

-

Gabaldon-style Negros Occidental High School (1927)

-

Buddhist Seng Guan Temple (20th century)

-

Neo-gothic feminist Molo Church

-

Bastion-style Baluarte de San Diego (1587)

Allied arts

[edit]Allied arts of architecture include interior design, landscape architecture, and urban design. Interior design has been influenced by indigenous Filipino culture, Hispanic, American and Japanese styles, modern design, the avant-garde, tropical design, neo-vernacular, international style, and sustainable design. Interior spaces, expressive of culture, values and aspirations, have been extensively researched by Filipino scholars.[291] Common interior design styles have been Tropical, Filipino, Japanese, Mediterranean, Chinese, Moorish, Victorian and Baroque, and Avant Garde Industrial, Tech and Trendy, Metallic Glam, Rustic Luxe, Eclectic Elegance, Organic Opulence, Design Deconstructed, and Funk Art have become popular.[292] Landscape architecture initially mirrored a client's opulence, but presently emphasizes ecosystems and sustainability.[293] Urban planning is a key economic and cultural issue because of the country's large population and problems with infrastructure such as transportation. Urban planners have proposed raising some urban areas, especially in congested and flood-prone Metro Manila.[294][295]

-

Interior of Betis Church, a National Cultural Treasure

-

Interior of San Sebastian Church, a National Cultural Treasure

-

Interior of San Agustin Church, a National Cultural Treasure

-

Urban design for Intramuros, 1734

-

Balay Negrense interior

-

Dapitan Church interior

-

Wright Park in front of the Baguio Mansion

-

Dapitan's Mindanao relief map (c. 1892), a National Cultural Treasure

-

Casa Manila courtyard

-

Paco Park, a National Cultural Treasure

Design

[edit]Design encompasses industrial and fashion design.

Industrial design

[edit]Industrial design has been a factor in improving the Philippine economy. Many artistic creations are through research and development, which attracts customers. The packaging of food and other products and the aesthetics of gadgets are examples of industrial design with the aesthetics of mass-produced vehicles, kitchen equipment and utensils, and furniture.[296][297] Design Week has been held during the third week of March and October since 2011.[298]

-

Various jewelries

-

Earth-tone bags

-

Angel ornament made of capiz shell, silver, and metal

-

Rattan rocking chair

Fashion design

[edit]Fashion is one of the Philippines' oldest artistic crafts, and each ethnic group has an individual fashion sense. Indigenous fashion uses materials created with the traditional arts, such as weaving and the ornamental arts. Unlike industrial design (which is intended for objects and structures), fashion design is a bodily package. Filipino fashion is based on indigenous fashion and aesthetics introduced by other Asian peoples and the West through trade and colonization. Ilustrado fashion was prevalent during the last years of the Hispanic era, and many people wore Hispanized outfits; this slowly changed as American culture was imported.[300] Budget-friendly choices prevail in modern Filipino fashion, although expensive fashions are available for the wealthy.[301] Outfits using indigenous Filipino textiles, without cultural appropriation, have become popular in the country.[302]

-

Tagalog royal fashion (1590)

-

Visayan royal fashion (1590)

-

Contemporary fashion

Preservation

[edit]Museums protect and conserve Philippine arts. A number of museums in the country possess works of art which have been declared National Treasures, particularly the National Museum of the Philippines in Manila. Other notable museums include the Ayala Museum, Negros Museum, Museo Sugbo, Lopez Museum, and Metropolitan Museum of Manila. University museums also hold a large collection of art.[303] The best-known libraries and archives are the National Library of the Philippines and the National Archives of the Philippines.[304] Organizations, groups, and universities also preserve the arts, especially the performing and craft arts.[304]

Heritage management in the Philippines includes preservation measures by private and public institutions and organizations, and laws such as the National Cultural Heritage Act have aided the conservation of Filipino art. The act established the Philippine Registry of Cultural Property, the country's repository of its cultural heritage.[305] The National Commission for Culture and the Arts, established by law in 1992, is the cultural arm of the Philippine government, and a Philippine Department of Culture has been proposed.[306][307]

Artistic freedom

[edit]Freedom of speech and freedom of the press are enshrined in the 1987 Constitution. According to the Constitution, under Article XVI, Section 10, the State is obligated to "provide the policy environment for … the balanced flow of information into, out of, and across the country, in accordance with a policy that respects the freedom of speech and of the press." The Constitution also guarantees freedom of the press under Article III, Section 4.[308] The Office of the President is responsible for managing the government's policy toward the press.

The Philippines is also a signatory to the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which aims to protect freedom of expression and the freedom of the press.[309]Censorship

[edit]In 2011, the Cultural Center of the Philippines took down the group exhibit Kulo (Boil) following pressure from religious leaders and politicians to remove the multimedia installation "Poleteismo" by Mideo Cruz. The installation prompted public debate on art and censorship[310] and its subsequent removal sparked protests from democracy and freedom of expression advocates.[311]

See also

[edit]- Baroque Churches of the Philippines

- Culture of the Philippines

- Filipino cartoon and animation

- List of Intangible Cultural Heritage elements in the Philippines

- List of Memory of the World Documentary Heritage in the Philippines

- List of World Heritage Sites in the Philippines

- Literature of the Philippines

- Philippine comics

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Gawad sa Manlilikha ng Bayan Guidelines". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c Order of National Artist Guidelines Approved on April 27, 2017 (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 29, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ a b Pag-iwayan, Jessica (November 2, 2020). "Albularyo, Babaylan, and Manghihilot Are Now Considered National Living Treasures". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- ^ Kroeber, A. L. (1918). The History of Philippine Civilization as Reflected in Religious Nomenclature. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. 19, Part 2. New York: Published by Order of the Trustees. pp. 35–37. hdl:2246/286.

- ^ Cole, Fay-Cooper (1922). The Tinguian: Social, Religious, and Economic Life of a Philippine Tribe. Anthropological Series, Vol.14, No. 2. Additional chapter by Albert Gale. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History. pp. 235–493.

- ^ Gaioni, Dominic T. (1985). "The Tingyans of Northern Philippines and Their Spirit World". Anthropos. 80 (4/6): 381–401. JSTOR 40461052.

- ^ "A Look at Philippine Mosques". ncca.gov.ph. October 6, 2003. Archived from the original on July 22, 2018. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Historic City of Vigan". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Klassen, Winand W. (1986). Architecture in the Philippines: Filipino Building in a Cross-Cultural Context. Cebu City: University of San Carlos.

- ^ Ignacio, Jose F. (n.d.). Heritage Architecture of Batanes Islands in the Philippines: A Survey of Different House Types and Their Evolution (PDF) – via hdm.lth.se.

- ^ Perez, Rodrigo D. III; Encarnacion, Rosario S.; Dacanay, Julian E. (1989). Folk Architecture. Photographs by Joseph R. Fortin and John K. Chua. Quezon City: GCF Books.

- ^ "Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Lacsina, Ligaya (2014). "Re-examining the Butuan Boats: Pre-colonial Philippine watercraft". National Museum of the Philippines.

- ^ Lacsina, Ligaya (2016). "Boats of the Precolonial Philippines: Butuan Boats". Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. pp. 948–954. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7747-7_10279. ISBN 978-94-007-7746-0.

- ^ Rosario, Ben (November 30, 2015). "Malay Ancestors' 'Balangay' Declared PH's National Boat". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015.

- ^ "Asia". Commercial Fisheries Review. Vol. 30, no. 8–9. August–September 1968. p. 96.

- ^ Roxas-Lim, Aurora. Traditional Boatbuilding and Philippine Maritime Culture (PDF). International Information and Networking Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region under the auspices of UNESCO (ICHCAP). pp. 219–222. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "Traditional Boats in Batanes" (PDF). International Information and Networking Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (ICHCAP). UNESCO. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ Madale, Abdullah T. (1997). The Maranaws: Dwellers of the Lake. Manila: Rex Book Store. p. 82. ISBN 971-23-2174-6.

- ^ Lozano, José Honorato (1847). Vistas de las islas Filipinas y trajes de sus habitantes.

- ^ Abrera, Maria Bernadette L. (2005). "Bangka, Kaluluwa at Katutubong Paniniwala" (PDF). Philippine Social Sciences Review (in Filipino). 57 (1–4): 1–15.

- ^ a b c d e f Nimmo, H. Arlo (1990). "The Boats of the Tawi-Tawi Bajau, Sulu Archipelago, Philippines". Asian Perspectives. 29 (1): 51–88. hdl:10125/16980. S2CID 31792662.

- ^ Kawamura, Gunzo; Bagarinao, Teodora (1980). "Fishing Methods and Gears in Panay Island, Philippines". Memoirs of Faculty of Fisheries Kagoshima University. 29: 81–121.

- ^ "Bigiw-Bugsay: Upholding Traditional Sailing". BusinessMirror. May 6, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ Galang, Ricardo E. (1941). "Types of Watercraft in the Philippines". The Philippine Journal of Science. 75 (3): 291–306.

- ^ Warren, James Francis (1985). "The Prahus of the Sulu Zone" (PDF). Brunei Museum Journal. 6: 42–45.

- ^ Roe, E. T.; Hooker, Le Roy; Handford, Thomas W., eds. (1907). The New American Encyclopedic Dictionary. New York: J. A. Hill & Company. p. 484.

- ^ Banagudos, Rey-Luis (December 26, 2018). "Wooden Boatmaking Embraces Mindanao Life, Culture". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ Argensola, Bartolomé Leonardo de (1711). "The Discovery and Conquest of the Molucco and Philippine Islands". In Stevens, John (ed.). A New Collection of Voyages and Travels, Into Several Parts of the World, None of Them Ever Before Printed in English. p. 61.

- ^ Yule, Henry; Burnell, Arthur Coke (1886). Hobson-Jobson: Being a Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Words and Phrases and of Kindred Terms Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive. London: John Murray. p. 509.

- ^ Abrera, Maria Bernadette L. (2007). "The Soul Boat and the Boat-Soul: An Inquiry into the Indigenous "Soul"" (PDF). ResearchSEA. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2022. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ Lim, Frinston (November 25, 2016). "Sa Marilag na Lake Sebu Hitik ang Kalikasan, Kultura, Adventure". Inquirer Libre Davao (in Filipino). Retrieved July 23, 2019 – via PressReader.

- ^ Diamond, Isobel (March 26, 2015). "Palawan by Paraw Boat". Travel+Leisure. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- ^ Warren, James Francis. The Sulu Zone, 1768–1898: The Dynamics of External Trade, Slavery, and Ethnicity in the Transformation of a Southeast Asian Maritime State (2nd ed.). Singapore: NUS Press.

- ^ Deveza, JB R. (February 21, 2010). "National Pride Sails in Ancient Boats". Philippine Daily Inquirer – via PressReader.

- ^ Doran, Edwin (1972). "Wa, Vinta, and Trimaran". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 81 (2): 144–159. JSTOR 20704848.

- ^ Medillo, Robert Joseph P. (June 19, 2015). "Forgotten History? the Polistas of the Galleon Trade". Rappler. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ Patterns of Culture (PDF). Retrieved July 24, 2020 – via unesco-ichcap.org.

- ^ Back-strap Weaving (PDF). Retrieved July 24, 2020 – via unesco-ichcap.org.

- ^ Sorilla, Franz IV (May 10, 2017). "Weaving the Threads of Filipino Heritage". Tatler Philippines.

- ^ Ocampo, Ambeth R. (October 19, 2011). "History and Design in Death Blankets". Opinion. Philippine Daily Inquirer.

- ^ Nocheseda, Elmer I. (2016). Rara: Art and Tradition of Mat Weaving in the Philippines. Makati City: The Philippine Textile Council. OCLC 982066949.

- ^ Pazon, Andy Nestor Ryan; Del Rio, Joana Marie P. (2018). "Materials, Functions and Weaving Patterns of Philippine Indigenous Baskets". Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies. 1 (2): 107–118. Archived from the original on November 6, 2021.

- ^ Yuvuk (PDF). Retrieved July 25, 2020 – via unesco-ichcap.org.

- ^ Smith-Lathouris, Olivana (January 4, 2019). "Thanks to These Filipino Women, Basket Weaving Is Revolutionising Entire Communities". SBS. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ a b "Salakkot and other headgear" (PDF). www.unesco-ichcap.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 24, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Bubo and other fish traps" (PDF). www.unesco-ichcap.org. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Saked brrom-making" (PDF). www.unesco-ichcap.org. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Peralta, Jesus T. (July–August 1983). "Prehistoric Gold Ornaments From the Central Bank of the Philippines". Arts of Asia. pp. 54–60.

- ^ Zafra, Jessica (April 26, 2008). "Art Exhibit: Philippines' 'Gold of Ancestors'". Newsweek. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Legeza, Laszlo (1988). "Tantric Elements in Pre-Hispanic Gold Art". Arts of Asia. Vol. 18, no. 4. pp. 129–133.

- ^ "History of Palawan". Camperspoint. Archived from the original on January 15, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- ^ "Early Buddhism in the Philippines". Buddhism in the Philippines. November 8, 2014.

- ^ Francisco, Juan R. (1963). "A Note on the Golden Image of Agusan". Philippine Studies. 11 (3): 390–400. doi:10.13185/2244-1638.2756. JSTOR 42719871.

It was found in 1917 on the left bank of the Wawa River near Esperanza, Agusan, eastern Mindanao, following a storm and flood

- ^ Francisco, Juan R. (1963). "A Note on the Golden Image of Agusan". Philippine Studies. 11 (3): 390–400. doi:10.13185/2244-1638.2756. JSTOR 42719871.

The question of its identification is still undecided.

- ^ a b "FMNH 109928". Field Museum. Archived from the original on June 1, 2019.

Statue [figure] is about 178 mm in height (FMNH A109928).

- ^ Onyot, Ian (March 23, 2012). "Agusan Gold Image Only in the Philippines". MagWrite.info. Archived from the original on June 27, 2012.

- ^ Agusan Image Documents, Agusan-Surigao Historical Archives.

- ^ a b c Churchill, Malcolm H. (1977). "Indian Penetration of Pre-Spanish Philippines: A New Look at the Evidence" (PDF). Asian Studies. 15: 21–45.

- ^ "Tribhanga: Strike A Pose". yet.typepad.com. Archived from the original on January 15, 2009. Retrieved January 6, 2007.

- ^ Francisco, Juan R. (January 1, 1963). "A Buddhist Image from Karitunan Site, Batangas Province" (PDF). Asian Studies: Journal of Critical Perspectives on Asia. 1. University of the Philippines Diliman: 13–22. ISSN 2244-5927.

- ^ Bennett, Anna T. N. (2009). "Gold in Early Southeast Asia". ArchéoSciences. 33 (33): 99–107. doi:10.4000/archeosciences.2072.

- ^ Dang, Van Thang; Vu, Quoc Hien (1977). "The Excavation at Giong Ca Vo Site". Journal of Southeast Asian Archaeology. 17: 30–37.

- ^ Caparas, Olympio V.; Lim, Valentine Mariel L.; Vargas, Nestor S. (1992). "Handicrafts and Folkcrafts Industries in the Philippines: Their Socio-Cultural and Economic Context". SPAFA Journal. 2 (1): 22–26.

- ^ Camacho, Leni D.; Gevaña, Dixon T.; Carandang, Antonio P.; Camacho, Sofronio C. (2016). "Indigenous Knowledge and Practices for the Sustainable Management of Ifugao Forests in Cordillera, Philippines". International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management. 12 (1–2): 5–13. Bibcode:2016IJBSE..12....5C. doi:10.1080/21513732.2015.1124453.

- ^ "Butuan Boat". National Museum. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Buenafe, Mayo (2011). "The Legal Pluralism Phenomenon: Emerging Issues on Protecting and Preserving the Sacred Ifugao Bulul". Nebraska Anthropologist. 26: 127–146.

- ^ Dancel, Manlou M. (1989). "The Ifugao Wooden Idol". SPAFA Digest. Vol. 10, no. 1. pp. 2–5.

- ^ Arcilla, Jose S. (1971). "The Christianization of Davao Oriental: Excerpts from Jesuit Missionary Letters". Philippine Studies. 19 (4): 639–724. doi:10.13185/2244-1638.2104. JSTOR 42632131.

- ^ Peralta, Jesus T. (1982). "Southwestern Philippine Art". SPAFA Digest. Vol. 3, no. 1. pp. 32–34.

- ^ Benesa, Leonidas V. (1982). Okir: The Epiphany of Philippine Graphic Art. Manila: Interlino Printing Company.

- ^ Barbosa, Artemio C. (1991). "Persisting Traditions of Folk Arts and Handicrafts in the Philippines". SPAFA Journal. 1 (1): 54–60.

- ^ Lasco, Lorenz (2011). "Ang Kosmolohiya at Simbolismo ng mga Sandatang Pilipino: Isang Panimulang Pag-Aaral". Dalumat e-Journal (in Filipino). 2 (1) – via Philippine E-Journals.

- ^ a b Baraoidan, Kimmy (April 28, 2019). "Wood Carving Art Alive in Paete". Inquirer.net.

- ^ Sánchez Gómez, Luis Ángel (2002). "Indigenous Art at the Philippine Exposition of 1887: Arguments for an Ideological and Racial Battle in a Colonial Context" (PDF). Journal of the History of Collections. 14 (2): 283–294. doi:10.1093/jhc/14.2.283.

- ^ Wood Connections: Creating Spaces and Possibilities for Wood Carvers in the Philippines, CD Habito, AV Mariano, 2014

- ^ National Museum (2010). Annual Report 2010 (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 13, 2020.

- ^ "PH National Museum receives valuable Philippine artifact". Southeast Asian Archeology. Philippines. January 27, 2020. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ Junker, Laura Lee (1999). Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2035-5.

- ^ "Remains of 1,000-Year Old Village Unearthed in Philippines". Daily News. Associated Press. September 20, 2012.

- ^ Baradas, David B. (1968). "Some Implications of the Okir Motif in Lanao and Sulu Art". Asian Studies. 6 (2): 129–168. S2CID 27892222.

- ^ "Kabayan Mummy Burial Caves". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ^ Torres, Sophia (June 5, 2014). "Romblon: The Country's Marble Capital is also an Island Haven". GMA News Online. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Reyes, Raquel A. G. (2019). "Paradise in Stone: Representations of New World Plants and Animals on Spanish Colonial Churches in the Philippines". In Reyes, Raquel A. G. (ed.). Art, Trade, and Cultural Mediation in Asia, 1600–1950. London: Palgrave Pivot. pp. 43–74. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-57237-0_3. ISBN 978-1-137-57236-3. S2CID 192379096.

- ^ a b "Baroque Churches of the Philippines". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ^ "Butuan Ivory Seal". National Museum. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ a b Intramuros Administration. "Rebultong Garing: Religious Images in Ivory". Google Arts & Culture (Photo slideshow). Archived from the original on January 30, 2023. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ Martin, Esmond; Martin, Chryssee; Vigne, Lucy (2011). "The Importance of Ivory in Philippine Culture" (PDF). Pachyderm. 50: 56–67.

- ^ Christy, Bryan (June 19, 2013). "In Global First, Philippines to Destroy its Ivory Stock". National Geographic. Archived from the original on January 14, 2020.

- ^ Madale, Abdullah T. (1997). The Maranaws: Dwellers of the Lake. Manila: Rex Book Store. ISBN 971-23-2174-6.

- ^ Duangwises, Narupon; Skar, Lowell D., eds. (2016). The Folk Performing Arts in ASEAN. Bangkok: Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre. ISBN 978-616-7154-36-7 – via Museum Siam Digital Repository.

- ^ a b "Cordillera". seasite.niu.edu. Archived from the original on August 5, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ a b "Muslim Mindanao". seasite.niu.edu.

- ^ a b Santos, Monica Fides Amada (2019). "Philippine Folk Dances: A Story of a Nation". Journal of English Studies and Comparative Literature. 18 (1): 1–38.