Astronomy

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 32 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 32 min

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, galaxies, meteoroids, asteroids, and comets. Relevant phenomena include supernova explosions, gamma ray bursts, quasars, blazars, pulsars, and cosmic microwave background radiation. More generally, astronomy studies everything that originates beyond Earth's atmosphere. Cosmology is the branch of astronomy that studies the universe as a whole.

Astronomy is one of the oldest natural sciences. The early civilizations in recorded history made methodical observations of the night sky. These include the Egyptians, Babylonians, Greeks, Indians, Chinese, Maya, and many ancient indigenous peoples of the Americas. In the past, astronomy included disciplines as diverse as astrometry, celestial navigation, observational astronomy, and the making of calendars.

Professional astronomy is split into observational and theoretical branches. Observational astronomy is focused on acquiring data from observations of astronomical objects. This data is then analyzed using basic principles of physics. Theoretical astronomy is oriented toward the development of computer or analytical models to describe astronomical objects and phenomena. These two fields complement each other. Theoretical astronomy seeks to explain observational results and observations are used to confirm theoretical results.

Astronomy is one of the few sciences in which amateurs play an active role. This is especially true for the discovery and observation of transient events. Amateur astronomers have helped with many important discoveries, such as finding new comets.

Etymology

[edit]Astronomy (from the Greek ἀστρονομία from ἄστρον astron, "star" and -νομία -nomia from νόμος nomos, "law" or "rule") means study of celestial objects.[1] Astronomy should not be confused with astrology, the belief system which claims that human affairs are correlated with the positions of celestial objects. The two fields share a common origin but became distinct, astronomy being supported by physics while astrology is not.[2]

Use of terms "astronomy" and "astrophysics"

[edit]"Astronomy" and "astrophysics" are broadly synonymous in modern usage.[3][4][5] In dictionary definitions, "astronomy" is "the study of objects and matter outside the Earth's atmosphere and of their physical and chemical properties",[6] while "astrophysics" is the branch of astronomy dealing with "the behavior, physical properties, and dynamic processes of celestial objects and phenomena".[7] Sometimes, as in the introduction of the introductory textbook The Physical Universe by Frank Shu, "astronomy" means the qualitative study of the subject, whereas "astrophysics" is the physics-oriented version of the subject.[8] Some fields, such as astrometry, are in this sense purely astronomy rather than also astrophysics. Research departments may use "astronomy" and "astrophysics" according to whether the department is historically affiliated with a physics department,[4] and many professional astronomers have physics rather than astronomy degrees.[5] Thus, in modern use, the two terms are often used interchangeably.[3]

History

[edit]Pre-historic

[edit]

In prehistoric times, people created artefacts such as the Nebra sky disc which serves as an astronomical calendar, defining a year as twelve lunar months, 354 days, with intercalary months to make up the solar year. The disc is inlaid with symbols interpreted as a sun, moon, and stars including a cluster of seven stars.[9][12][13]

Classical

[edit]

Civilizations such as Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, India, China together – with cross-cultural influences – created astronomical observatories and developed ideas on the nature of the Universe, along with calendars and astronomical instruments.[15] A key early development was the beginning of mathematical and scientific astronomy among the Babylonians, laying the foundations for astronomical traditions in other civilizations.[16] The Babylonians discovered that lunar eclipses recurred in the saros cycle of 223 synodic months.[17]

Following the Babylonians, significant advances were made in ancient Greece and the Hellenistic world. Greek astronomy sought a rational, physical explanation for celestial phenomena.[18] In the 3rd century BC, Aristarchus of Samos estimated the size and distance of the Moon and Sun, and he proposed a model of the Solar System where the Earth and planets rotated around the Sun, now called the heliocentric model.[19] In the 2nd century BC, Hipparchus discovered precession, calculated the size and distance of the Moon and invented the earliest known astronomical devices such as the astrolabe.[20] Hipparchus also created a catalog of 1020 stars, and most of the constellations of the northern hemisphere derive from Greek astronomy.[21] The Antikythera mechanism (c. 150–80 BC) was an early analog computer designed to calculate the location of the Sun, Moon, and planets for a given date. Technological artifacts of similar complexity did not reappear until the 14th century, when mechanical astronomical clocks appeared in Europe.[22]

After the classical Greek era, astronomy was dominated by the geocentric model of the Universe, or the Ptolemaic system, named after Ptolemy. In this system, the Earth was believed to be the center of the Universe with the Sun, the Moon and the stars rotating around it.[23]

Post-classical

[edit]

Astronomy flourished in the medieval Islamic world. Astronomical observatories were established there by the early 9th century.[25][26][27] In 964, the Andromeda Galaxy, the largest galaxy in the Local Group, was described by the Persian Muslim astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi in his Book of Fixed Stars.[28] The SN 1006 supernova, the brightest apparent magnitude stellar event in the last 1000 years, was observed by the Egyptian Arabic astronomer Ali ibn Ridwan and Chinese astronomers in 1006.[29] Iranian scholar Al-Biruni observed that, contrary to Ptolemy, the Sun's apogee (highest point in the heavens) was mobile, not fixed.[30][31] Arabic astronomers introduced many Arabic names now used for individual stars.[32]

The ruins at Great Zimbabwe and Timbuktu[33] may have housed astronomical observatories.[34] In Post-classical West Africa, astronomers studied the movement of stars and relation to seasons, crafting charts of the heavens and diagrams of orbits of the other planets based on complex mathematical calculations. Songhai historian Mahmud Kati documented a meteor shower in 1583.[35][36]

In medieval Europe, Richard of Wallingford (1292–1336) invented the first astronomical clock, the Rectangulus which allowed for the measurement of angles between planets and other astronomical bodies,[37] as well as an equatorium called the Albion which could be used for astronomical calculations such as lunar, solar and planetary longitudes.[38] Nicole Oresme (1320–1382) discussed evidence for the rotation of the Earth.[39] Jean Buridan (1300–1361) developed the theory of impetus, describing motions including of the celestial bodies.[40][41] For over six centuries (from the recovery of ancient learning during the late Middle Ages into the Enlightenment), the Roman Catholic Church gave more financial and social support to the study of astronomy than probably all other institutions. Among the Church's motives was finding the date for Easter.[42]

Early telescopic

[edit]

During the Renaissance, Nicolaus Copernicus proposed a heliocentric model of the solar system.[43] His work was defended by Galileo Galilei and expanded upon by Johannes Kepler.[44] Kepler was the first to devise a system that correctly described the details of the motion of the planets around the Sun. However, Kepler did not succeed in formulating a theory behind the laws he wrote down.[45] It was Isaac Newton, with his invention of celestial dynamics and his law of gravitation, who finally explained the motions of the planets.[46] Newton also developed the reflecting telescope.[47]

The English astronomer John Flamsteed, Britain's first Astronomer Royal, catalogued over 3000 stars.[48] More extensive star catalogues were produced by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille. The astronomer William Herschel made a detailed catalog of nebulosity and clusters, and in 1781 discovered the planet Uranus, the first new planet found.[49]

During the 18–19th centuries, the study of the three-body problem by Leonhard Euler, Alexis Claude Clairaut, and Jean le Rond d'Alembert led to more accurate predictions about the motions of the Moon and planets. This work was further refined by Joseph-Louis Lagrange and Pierre Simon Laplace, allowing the masses of the planets and moons to be estimated from their perturbations.[50]

Significant advances in astronomy came about with the introduction of new technology, including the spectroscope and astrophotography. In 1814–15, Joseph von Fraunhofer discovered some 574 dark lines in the spectrum of the sun and of other stars.[51][52] In 1859, Gustav Kirchhoff ascribed these lines to the presence of different elements.[53]

Deep space

[edit]

The existence of the Earth's galaxy, the Milky Way, as its own group of stars was only proven in the 20th century, along with the existence of other galaxies. The observed recession of those galaxies led to the discovery of the expansion of the Universe.[54] Using the Hooker Telescope, Edwin Hubble identified Cepheid variables in several spiral nebulae and in 1922–1923 proved conclusively that Andromeda Nebula and Triangulum among others, were entire galaxies outside our own, thus proving that the universe consists of a multitude of galaxies.[55] With this, Hubble formulated the Hubble constant, which enabled a calculation of the age of the Universe and the size of the Observable Universe. Such calculations became increasingly precise with better measurements, starting at 2 billion years and 280 million light-years, until 2006 when data of the Hubble Space Telescope supported very accurate calculations.[56]

Theoretical astronomy predicted the existence of objects such as black holes[57] and neutron stars.[58] These have been used to explain phenomena such as quasars[59] and pulsars.[60] As for physical cosmology, in the early 20th century the Big Bang theory of the universe was formulated, evidenced by cosmic microwave background radiation and Hubble's law.[61]

Space telescopes have enabled measurements in parts of the electromagnetic spectrum normally blocked or blurred by the atmosphere.[62] The LIGO project detected evidence of gravitational waves in 2015.[63][64]

Observational astronomy

[edit]

The main source of information about celestial bodies and other objects is visible light, or more generally electromagnetic radiation.[65] Observational astronomy may be categorized according to the corresponding region of the electromagnetic spectrum on which the observations are made. Specific information on these subfields is given below.

Radio

[edit]

Radio astronomy uses radiation with long wavelengths, mainly between 1 millimeter and 15 meters (frequencies from 20 MHz to 300 GHz), far outside the visible range.[66] Hydrogen, otherwise an invisible gas, produces a spectral line at 21 cm (1420 MHz) which is observable at radio wavelengths.[67] Objects observable at radio wavelengths include interstellar gas,[67] pulsars,[67] fast radio bursts,[67] supernovae,[68] and active galactic nuclei.[69]

Infrared

[edit]

Infrared astronomy is founded on the detection and analysis of infrared radiation, wavelengths longer than red light and outside the range of our vision. The infrared spectrum is useful for studying objects that are too cold to radiate visible light, such as planets, circumstellar disks or nebulae whose light is blocked by dust. The longer wavelengths of infrared can penetrate clouds of dust that block visible light, allowing the observation of young stars embedded in molecular clouds and the cores of galaxies. Observations from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) have been particularly effective at unveiling numerous galactic protostars and their host star clusters.[70][71] With the exception of infrared wavelengths close to visible light, such radiation is heavily absorbed by the atmosphere, or masked, as the atmosphere itself produces significant infrared emission. Consequently, infrared observatories have to be located in high, dry places on Earth or in space.[72] Some molecules radiate strongly in the infrared. This allows the study of the chemistry of space.[73]

Optical

[edit]Historically, optical astronomy, which has been also called visible light astronomy, is the oldest form of astronomy.[74] Images of observations were originally drawn by hand. In the late 19th century and most of the 20th century, images were made using photographic equipment. Modern images are made using digital detectors, particularly using charge-coupled devices (CCDs) and recorded on modern medium. Although visible light itself extends from approximately 380 to 700 nm[75] that same equipment can be used to observe some near-ultraviolet and near-infrared radiation.[76]

Ultraviolet

[edit]Ultraviolet astronomy employs ultraviolet wavelengths which are absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere, requiring observations from the upper atmosphere or from space. Ultraviolet astronomy is best suited to the study of thermal radiation and spectral emission lines from hot blue OB stars that are very bright in this wave band.[77]

X-ray

[edit]

X-ray astronomy uses X-radiation, produced by extremely hot and high-energy processes. Since X-rays are absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere, observations must be performed at high altitude, such as from balloons, rockets, or specialized satellites. X-ray sources include X-ray binaries, supernova remnants, clusters of galaxies, and active galactic nuclei.[78]

Gamma-ray

[edit]Gamma ray astronomy observes astronomical objects at the shortest wavelengths (highest energy) of the electromagnetic spectrum. Gamma rays may be observed directly by satellites such as the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory,[79] or by specialized telescopes called atmospheric Cherenkov telescopes. Cherenkov telescopes do not detect the gamma rays directly but instead detect the flashes of visible light produced when gamma rays are absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere.[80][81] Gamma-ray bursts, which radiate transiently, are extremely energetic events, and are the brightest (most luminous) phenomena in the universe.[82]

Fields not based on the electromagnetic spectrum

[edit]

Some events originating from great distances may be observed from the Earth using systems that do not rely on electromagnetic radiation.[83][84]

In neutrino astronomy, astronomers use heavily shielded underground facilities such as SAGE, GALLEX, and Kamioka II/III for the detection of neutrinos. The vast majority of the neutrinos streaming through the Earth originate from the Sun, but 24 neutrinos were also detected from supernova 1987A. Cosmic rays, which consist of very high energy particles (atomic nuclei) that can decay or be absorbed when they enter the Earth's atmosphere, result in a cascade of secondary particles which can be detected by current observatories.[83]

Gravitational-wave astronomy employs gravitational-wave detectors to collect observational data about distant massive objects. A few observatories have been constructed, such as the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Observatory LIGO. LIGO made its first detection on 14 September 2015, observing gravitational waves from a binary black hole.[84][85] A second gravitational wave was detected on 26 December 2015 and additional observations should continue but gravitational waves require extremely sensitive instruments.[86][87]

The combination of observations made using electromagnetic radiation, neutrinos or gravitational waves and other complementary information, is known as multi-messenger astronomy.[88][89]

Astrometry and celestial mechanics

[edit]

One of the oldest fields in astronomy, and in all of science, is the measurement of the positions of celestial objects. Historically, accurate knowledge of the positions of the Sun, Moon, planets and stars has been essential in celestial navigation (the use of celestial objects to guide navigation) and in the making of calendars.[90] Careful measurement of the positions of the planets has led to a solid understanding of gravitational perturbations, and an ability to determine past and future positions of the planets with great accuracy, a field known as celestial mechanics.[91] The measurement of stellar parallax of nearby stars provides a fundamental baseline in the cosmic distance ladder that is used to measure the scale of the Universe. Parallax measurements of nearby stars provide an absolute baseline for the properties of more distant stars, as their properties can be compared.[92] Measurements of the radial velocity[93][94] and proper motion of stars allow astronomers to plot the movement of these systems through the Milky Way galaxy.[95]

Theoretical astronomy

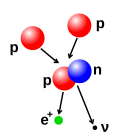

[edit]| Nucleosynthesis |

|---|

|

| Related topics |

Theoretical astronomers use several tools including analytical models and computational numerical simulations; each has its particular advantages. Analytical models of a process are better for giving broader insight into the heart of what is going on. Numerical models reveal the existence of phenomena and effects otherwise unobserved.[96][97] Modern theoretical astronomy reflects dramatic advances in observation since the 1990s, including studies of the cosmic microwave background, distant supernovae and galaxy redshifts, which have led to the development of a standard model of cosmology. This model requires the universe to contain large amounts of dark matter and dark energy whose nature is currently not well understood, but the model gives detailed predictions that are in excellent agreement with many diverse observations.[98]

Subfields by scale

[edit]Physical cosmology

[edit]

Physical cosmology, the study of large-scale structure of the Universe, seeks to understand the formation and evolution of the cosmos. Fundamental to modern cosmology is the well-accepted theory of the Big Bang, the concept that the universe begin extremely dense and hot, then expanded over the course of 13.8 billion years[99] to its present condition.[100] The concept of the Big Bang became widely accepted after the discovery of the microwave background radiation in 1965.[100] Fundamental to the structure of the Universe is the existence of dark matter and dark energy. These are now thought to be its dominant components, forming 96% of the mass of the Universe. For this reason, much effort is expended in trying to understand the physics of these components.[101]

Extragalactic

[edit]

The study of objects outside our galaxy is concerned with the formation and evolution of galaxies, their morphology (description) and classification, the observation of active galaxies, and at a larger scale, the groups and clusters of galaxies. These assist the understanding of the large-scale structure of the cosmos.[90]

Galactic

[edit]Galactic astronomy studies galaxies including the Milky Way, a barred spiral galaxy that is a prominent member of the Local Group of galaxies and contains the Solar System. It is a rotating mass of gas, dust, stars and other objects, held together by mutual gravitational attraction. As the Earth is within the dusty outer arms, large portions of the Milky Way are obscured from view.[90]: 837–842, 944

Kinematic studies of matter in the Milky Way and other galaxies show there is more mass than can be accounted for by visible matter. A dark matter halo appears to dominate the mass, although the nature of this dark matter remains undetermined.[102]

Stellar

[edit]The study of stars and stellar evolution is fundamental to our understanding of the Universe. The astrophysics of stars has been determined through observation and theoretical understanding; and from computer simulations of the interior.[103] Aspects studied include star formation in giant molecular clouds; the formation of protostars; and the transition to nuclear fusion and main-sequence stars,[104] carrying out nucleosynthesis.[103] Further processes studied include stellar evolution,[105] ending either with supernovae[106] or white dwarfs. The ejection of the outer layers forms a planetary nebula.[107] The remnant of a supernova is a dense neutron star, or, if the stellar mass was at least three times that of the Sun, a black hole.[108]

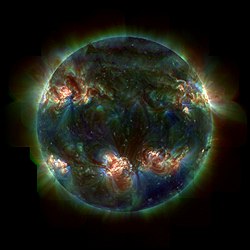

Solar

[edit]

Solar astronomy is the study of the Sun, a typical main-sequence dwarf star of stellar class G2 V, and about 4.6 billion years (Gyr) old. Processes studied by the science include the sunspot cycle,[109] the sun's changes in luminosity, both steady and periodic,[110][111] and the behavior of the sun's various layers, namely its core with its nuclear fusion, the radiation zone, the convection zone, the photosphere, the chromosphere, and the corona.[90]: 498–502

Planetary science

[edit]

Planetary science is the study of the assemblage of planets, moons, dwarf planets, comets, asteroids, and other bodies orbiting the Sun, as well as extrasolar planets. The Solar System has been relatively well-studied, initially through telescopes and then later by spacecraft.[112][113]

Processes studied include planetary differentiation; the generation of, and effects created by, a planetary magnetic field;[114] and the creation of heat within a planet, such as by collisions, radioactive decay, and tidal heating. In turn, that heat can drive geologic processes such as volcanism, tectonics, and surface erosion, studied by branches of geology.[115]

Interdisciplinary subfields

[edit]Astrochemistry

[edit]Astrochemistry is an overlap of astronomy and chemistry. It studies the abundance and reactions of molecules in the Universe, and their interaction with radiation. The word "astrochemistry" may be applied to both the Solar System and the interstellar medium. Studies in this field contribute for example to the understanding of the formation of the Solar System.[116]

Astrobiology

[edit]Astrobiology (or exobiology[117]) studies the origin of life and its development other than on earth. It considers whether extraterrestrial life exists, and how humans can detect it if it does.[118] It makes use of astronomy, biochemistry, geology, microbiology, physics, and planetary science to investigate the possibility of life on other worlds and help recognize biospheres that might be different from that on Earth.[119] The origin and early evolution of life is an inseparable part of the discipline of astrobiology.[120] That encompasses research on the origin of planetary systems, origins of organic compounds in space, rock-water-carbon interactions, abiogenesis on Earth, planetary habitability, research on biosignatures for life detection, and studies on the potential for life to adapt to challenges on Earth and in outer space.[121][122][123]

Other

[edit]Astronomy and astrophysics have developed interdisciplinary links with other major scientific fields. Archaeoastronomy is the study of ancient or traditional astronomies in their cultural context, using archaeological and anthropological evidence.[124] Astrostatistics is the application of statistics to the analysis of large quantities of observational astrophysical data.[125] As "forensic astronomy", finally, methods from astronomy have been used to solve problems of art history[126][127] and occasionally of law.[128]

Amateur

[edit]

Astronomy is one of the sciences to which amateurs can contribute the most.[129] Collectively, amateur astronomers observe celestial objects and phenomena, sometimes with consumer-level equipment or equipment that they build themselves. Common targets include the Sun, the Moon, planets, stars, comets, meteor showers, and deep-sky objects such as star clusters, galaxies, and nebulae. Astronomy clubs throughout the world have programs to help their members set up and run observational programs such as to observe all the objects in the Messier (110 objects) or Herschel 400 catalogues.[130][131] Most amateurs work at visible wavelengths, but some have experimented with wavelengths outside the visible spectrum. The pioneer of amateur radio astronomy, Karl Jansky, discovered a radio source at the centre of the Milky Way.[132] Some amateur astronomers use homemade telescopes or radio telescopes originally built for astronomy research (e.g. the One-Mile Telescope).[133][134]

Amateurs can make occultation measurements to refine the orbits of minor planets. They can discover comets, and perform regular observations of variable stars. Improvements in digital technology have allowed amateurs to make advances in astrophotography.[135][136][137]

Unsolved problems

[edit]In the 21st century, there remain important unanswered questions in astronomy. Some are cosmic in scope: for example, what are the dark matter and dark energy that dominate the evolution and fate of the cosmos?[138] What will be the ultimate fate of the universe?[139] Why is the abundance of lithium in the cosmos four times lower than predicted by the standard Big Bang model?[140] Others pertain to more specific classes of phenomena. For example, is the Solar System normal or atypical?[141] What is the origin of the stellar mass spectrum, i.e. why do astronomers observe the same distribution of stellar masses—the initial mass function—regardless of initial conditions?[142] Likewise, questions remain about the formation of the first galaxies,[143] the origin of supermassive black holes,[144] the source of ultra-high-energy cosmic rays,[145] and whether there is other life in the Universe, especially other intelligent life.[146][147]

See also

[edit]- Cosmogony – Theory or model concerning the origin of the universe

- Outline of astronomy – Overview of the scientific field of astronomy

- Outline of space science – Overview of and topical guide to space science

- Space exploration – Exploration of space, planets, and moons

Lists

[edit]- Glossary of astronomy

- List of astronomers

- List of astronomical instruments

- List of astronomical observatories

- List of astronomy acronyms

- List of astronomical societies

- List of software for astronomy research and education

References

[edit]- ^ "astronomy (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- ^ Losev, Alexandre (2012). "'Astronomy' or 'astrology': A brief history of an apparent confusion". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 15 (1): 42–46. arXiv:1006.5209. Bibcode:2012JAHH...15...42L. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1440-2807.2012.01.05. ISSN 1440-2807. S2CID 51802196.

- ^ a b Scharringhausen, B. (January 2002). "What is the difference between astronomy and astrophysics?". Curious About Astronomy. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ a b Odenwald, Sten. "Archive of Astronomy Questions and Answers: What is the difference between astronomy and astrophysics?". The Astronomy Cafe. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ^ a b "School of Science-Astronomy and Astrophysics". Penn State Erie. 18 July 2005. Archived from the original on 1 November 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ^ "astronomy". Merriam-Webster Online. Archived from the original on 17 June 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ^ "astrophysics". Merriam-Webster Online. Archived from the original on 21 September 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ^ Shu, F.H. (1983). "Preface". The Physical Universe. Mill Valley, California: University Science Books. ISBN 978-0-935702-05-7.

- ^ a b Meller, Harald (2021). "The Nebra Sky Disc – astronomy and time determination as a source of power". Time is power. Who makes time?: 13th Archaeological Conference of Central Germany. Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte Halle (Saale). ISBN 978-3-948618-22-3.

- ^ Concepts of cosmos in the world of Stonehenge. British Museum. 2022.

- ^ Bohan, Elise; Dinwiddie, Robert; Challoner, Jack; Stuart, Colin; Harvey, Derek; Wragg-Sykes, Rebecca; Chrisp, Peter; Hubbard, Ben; Parker, Phillip; et al. (Writers) (February 2016). Big History. Foreword by David Christian (1st American ed.). New York: DK. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-4654-5443-0. OCLC 940282526.

- ^ "Nebra Sky Disc". Halle State Museum of Prehistory.

- ^ "The Nebra Sky Disc: decoding a prehistoric vision of the cosmos". The-Past.com. May 2022.

- ^ Gent, R.H. van. "Bibliography of Babylonian Astronomy & Astrology". science.uu.nl project csg. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ Sarma, Nataraja (2000). "Diffusion of astronomy in the ancient world". Endeavour. 24 (4): 157–164. doi:10.1016/S0160-9327(00)01327-2.

- ^ Aaboe, A. (1974). "Scientific Astronomy in Antiquity". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 276 (1257): 21–42. Bibcode:1974RSPTA.276...21A. doi:10.1098/rsta.1974.0007. JSTOR 74272. S2CID 122508567.

- ^ "Eclipses and the Saros". NASA. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- ^ Krafft, Fritz (2009). "Astronomy". In Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth (eds.). Brill's New Pauly.

- ^ Berrgren, J.L.; Sidoli, Nathan (May 2007). "Aristarchus's On the Sizes and Distances of the Sun and the Moon: Greek and Arabic Texts". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 61 (3): 213–54. doi:10.1007/s00407-006-0118-4. S2CID 121872685.

- ^ "Hipparchus of Rhodes". School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- ^ Thurston, H. (1996). Early Astronomy. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-387-94822-5. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Marchant, Jo (2006). "In search of lost time". Nature. 444 (7119): 534–538. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..534M. doi:10.1038/444534a. PMID 17136067.

- ^ DeWitt, Richard (2010). "The Ptolemaic System". Worldviews: An Introduction to the History and Philosophy of Science. Chichester, England: Wiley. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-4051-9563-8.

- ^ Akerman, Iain (17 May 2023). "The language of the stars". WIRED Middle East. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ Kennedy, Edward S. (1962). "Review: The Observatory in Islam and Its Place in the General History of the Observatory by Aydin Sayili". Isis. 53 (2): 237–39. doi:10.1086/349558.

- ^ Micheau, Françoise. Rashed, Roshdi; Morelon, Régis (eds.). "The Scientific Institutions in the Medieval Near East". Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. 3: 992–93.

- ^ Nas, Peter J (1993). Urban Symbolism. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 350. ISBN 978-90-04-09855-8.

- ^ Kepple, George Robert; Sanner, Glen W. (1998). The Night Sky Observer's Guide. Vol. 1. Willmann-Bell, Inc. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-943396-58-3.

- ^ Murdin, Paul; Murdin, Lesley (1985). Supernovae (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-521-30038-4.

- ^ Goldstein, Bernard R. (1967). "The Arabic version of Ptolemy's planetary hypothesis". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 57 (pt. 4): 6. doi:10.2307/1006040. JSTOR 1006040.

- ^ Covington, Richard (2007). "Rediscovering Arabic Science". Aramco World. Vol. 58, no. 3. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ Morrison, Robert G. (2013). "Astronomy in Islam". Encyclopedia of Sciences and Religions. pp. 155–158. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8265-8_89. ISBN 978-1-4020-8264-1.

- ^ McKissack, Pat; McKissack, Frederick (1995). The royal kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhay: life in medieval Africa. H. Holt. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-8050-4259-7.

- ^ Clark, Stuart; Carrington, Damian (2002). "Eclipse brings claim of medieval African observatory". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ^ Hammer, Joshua (2016). The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu And Their Race to Save the World's Most Precious Manuscripts. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-1-4767-7743-6.

- ^ Holbrook, Jarita C.; Medupe, R. Thebe; Johnson Urama (2008). African Cultural Astronomy. Springer. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-4020-6638-2. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ Gimpel, Jean (1992) [1976]. The Medieval Machine (2nd ed.). Pimlico. pp. 155–157. ISBN 978-0-7126-5484-5.

- ^ Hannam, James (2009). God's philosophers: how the medieval world laid the foundations of modern science. Icon Books. p. 180.

- ^ Grant, The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp. 114–116.

- ^ Questions on the Eight Books of the Physics of Aristotle: Book VIII Question 12. English translation in Clagett's 1959 Science of Mechanics in the Middle Ages , p. 536

- ^ Van Dyck, Maarten; Malara, Ivan. "Renaissance Concept of Impetus". Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Heilbron, J.L. (1999). The Sun in the Church: Cathedrals as Solar Observatories. Harvard University Press. p. 3.

- ^ Forbes 1909, Book 2, chapter 4: The Reign of Epicycles—From Ptolemy to Copernicus

- ^ Forbes 1909, Book 2, chapter 6: Galileo and the Telescope—Notionsl of gravity by Horrocks, etc.

- ^ Forbes 1909, Book 2, chapter 5: Discovery of the True Solar System—Tycho Brahe—Kepler

- ^ Forbes 1909, Book 2, chapter 7: Sir Isaac Newton—Law of Universal Gravitation

- ^ Forbes 1909, Book 3, chapter 10: History of the Telescope—Spectroscope

- ^ "Who was John Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal?". Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Forbes 1909, Book 2, chapter 9: Discovery of New Planets—Herschel, Piazzi, Adams, and Le Verrier

- ^ Forbes 1909, Book 2, chapter 8: Newton's Successors—Halley, Euler, Lagrange, Laplace, etc.

- ^ Ferguson, Kitty; Maciaszek, Miko (20 March 2014). "The Glassmaker Who Sparked Astrophysics". Nautilus. Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Buehrke, Thomas (2021). "Physics & Astronomy: Cosmic Detective Work" (PDF). Max Planck Research (4): 67–72.

- ^ Kirchhoff, G. (1860). "Ueber die Fraunhofer'schen Linien" [On Fraunhofer's Lines]. Annalen der Physik (in German). 185 (1): 148–150. Bibcode:1860AnP...185..148K. doi:10.1002/andp.18601850115.

- ^ Belkora, Leila (2003). Minding the heavens: the story of our discovery of the Milky Way. CRC Press. pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-0-7503-0730-7. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Sharov, Aleksandr Sergeevich; Novikov, Igor Dmitrievich (1993). Edwin Hubble, the discoverer of the big bang universe. Cambridge University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-521-41617-7. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ "Cosmic Times". Imagine the Universe!. 8 December 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^ Oppenheimer, J. R.; Volkoff, G. M. (1939). "On Massive Neutron Cores". Physical Review. 55 (4): 374–381. Bibcode:1939PhRv...55..374O. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.55.374.

- ^ Baade, Walter; Zwicky, Fritz (1934). "Remarks on Super-Novae and Cosmic Rays" (PDF). Physical Review. 46 (1): 76–77. Bibcode:1934PhRv...46...76B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.46.76.2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ Schmidt, M. (March 1963). "3C 273 : A Star-Like Object with Large Red-Shift". Nature. 197 (4872): 1040. Bibcode:1963Natur.197.1040S. doi:10.1038/1971040a0. S2CID 4186361.

- ^ Gold, T. (1968). "Rotating Neutron Stars as the Origin of the Pulsating Radio Sources". Nature. 218 (5143): 731–732. Bibcode:1968Natur.218..731G. doi:10.1038/218731a0. S2CID 4217682.

- ^ Nussbaumer, H.; Bieri, L. (2011). "Who discovered the expanding universe?". The Observatory. 131 (6): 394–398. arXiv:1107.2281. Bibcode:2011Obs...131..394N.

- ^ McLean, Ian S. (2008). "Beating the atmosphere". Electronic Imaging in Astronomy. Springer Praxis Books. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 39–75. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-76583-7_2. ISBN 978-3-540-76582-0.

- ^ Castelvecchi, Davide; Witze, Witze (11 February 2016). "Einstein's gravitational waves found at last". Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19361. S2CID 182916902. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ Abbott, B.P.; et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration) (2016). "Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger". Physical Review Letters. 116 (6) 061102. arXiv:1602.03837. Bibcode:2016PhRvL.116f1102A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.061102. PMID 26918975. S2CID 124959784.

- ^ "Electromagnetic Spectrum". NASA. Archived from the original on 5 September 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ "What is radio astronomy". RadioAstroLab. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d "What is radio astronomy?". SKAO. 2025. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- ^ "Radio Wave Emissions from Supernova 1987a". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 11 March 1987. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- ^ Radcliffe, J. F.; Barthel, P. D.; Garrett, M. A.; Beswick, R. J.; Thomson, A. P.; Muxlow, T. W. B. (2021). "The radio emission from active galactic nuclei" (PDF). Astronomy & Astrophysics. 649: L9. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202140791.

- ^ "Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer Mission". NASA University of California, Berkeley. 30 September 2014. Archived from the original on 12 January 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ Majaess, D. (2013). "Discovering protostars and their host clusters via WISE". Astrophysics and Space Science. 344 (1): 175–186. arXiv:1211.4032. Bibcode:2013Ap&SS.344..175M. doi:10.1007/s10509-012-1308-y. S2CID 118455708.

- ^ "Why infrared astronomy is a hot topic". ESA. 11 September 2003. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ^ "Infrared Spectroscopy – An Overview". NASA California Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 5 October 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- ^ Moore, Patrick (2007). "Invisible Astronomy". Philip's atlas of the universe (6., new ed.). London: Philip's. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0540091189.

- ^ "Visible Light - NASA Science". NASA.gov. NASA. 10 August 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ "Glossary term: Optical Astronomy". IAU Office of Astronomy for Education. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ Mohammed, Steven Matthew (2021). Probing the Ultraviolet Milky Way: The Final Galactic Puzzle Piece. Columbia University (PhD thesis). pp. 11–13.

- ^ Arnaud, Keith (2007). "An Introduction to X-ray Astronomy" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- ^ "The History of Gamma-ray Astronomy". NASA. Archived from the original on 20 May 1998. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ "MAGIC telescopes webpage". Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Penston, Margaret J. (14 August 2002). "The electromagnetic spectrum". Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ Gehrels, Neil; Mészáros, Péter (24 August 2012). "Gamma-Ray Bursts". Science. 337 (6097): 932–936. arXiv:1208.6522. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..932G. doi:10.1126/science.1216793. PMID 22923573.

- ^ a b Gaisser, Thomas K. (1990). Cosmic Rays and Particle Physics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-521-33931-5.

- ^ a b Abbott, Benjamin P.; et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration) (2016). "Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger". Physical Review Letters. 116 (6) 061102. arXiv:1602.03837. Bibcode:2016PhRvL.116f1102A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.061102. PMID 26918975. S2CID 124959784.

- ^ Moskowitz, Clara (11 February 2016). "Gravitational Waves Discovered from Colliding Black Holes". Scientific American.

- ^ Tammann, Gustav-Andreas; Thielemann, Friedrich-Karl; Trautmann, Dirk (2003). "Opening new windows in observing the Universe". Europhysics News. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration; Abbott, B. P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T. D.; Abernathy, M. R.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T. (15 June 2016). "GW151226: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a 22-Solar-Mass Binary Black Hole Coalescence". Physical Review Letters. 116 (24): 241103. arXiv:1606.04855. Bibcode:2016PhRvL.116x1103A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.241103. PMID 27367379. S2CID 118651851.

- ^ "Planning for a bright tomorrow: Prospects for gravitational-wave astronomy with Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo". LIGO Scientific Collaboration. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ Xing, Zhizhong; Zhou, Shun (2011). Neutrinos in Particle Physics, Astronomy and Cosmology. Springer. p. 313. ISBN 978-3-642-17560-2. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d Fraknoi, Andrew; et al. (2022). Astronomy 2e (2e ed.). OpenStax. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-951693-50-3. OCLC 1322188620. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ Calvert, James B. (28 March 2003). "Celestial Mechanics". University of Denver. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ "Climbing the cosmic distance ladder" (PDF). University of Western Australia. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Lindegren, Lennart; Dravins, Dainis (April 2003). "The fundamental definition of "radial velocity"" (PDF). Astronomy and Astrophysics. 401 (3): 1185–1201. arXiv:astro-ph/0302522. Bibcode:2003A&A...401.1185L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20030181. S2CID 16012160. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ Dravins, Dainis; Lindegren, Lennart; Madsen, Søren (1999). "Astrometric radial velocities. I. Non-spectroscopic methods for measuring stellar radial velocity". Astron. Astrophys. 348: 1040–1051. arXiv:astro-ph/9907145. Bibcode:1999A&A...348.1040D.

- ^ "Hall of Precision Astrometry". University of Virginia Department of Astronomy. Archived from the original on 26 August 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ Roth, H. (1932). "A Slowly Contracting or Expanding Fluid Sphere and its Stability". Physical Review. 39 (3): 525–529. Bibcode:1932PhRv...39..525R. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.39.525.

- ^ Eddington, A.S. (1926). "Internal Constitution of the Stars". Science. 52 (1341). Cambridge University Press: 233–40. Bibcode:1920Sci....52..233E. doi:10.1126/science.52.1341.233. ISBN 978-0-521-33708-3. PMID 17747682. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

{{cite journal}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Beringer, J.; et al. (Particle Data Group) (2012). "2013 Review of Particle Physics" (PDF). Physical Review D. 86 (1): 010001. Bibcode:2012PhRvD..86a0001B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.86.010001. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ "Cosmic Detectives". The European Space Agency (ESA). 2 April 2013. Archived from the original on 11 February 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ a b Dodelson, Scott (2003). Modern cosmology. Academic Press. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-12-219141-1.

- ^ Preuss, Paul. "Dark Energy Fills the Cosmos". U.S. Department of Energy, Berkeley Lab. Archived from the original on 11 August 2006. Retrieved 8 September 2006.

- ^ Van den Bergh, Sidney (1999). "The Early History of Dark Matter". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 111 (760): 657–60. arXiv:astro-ph/9904251. Bibcode:1999PASP..111..657V. doi:10.1086/316369. S2CID 5640064.

- ^ a b Harpaz, 1994, pp. 7–18

- ^ Smith, Michael David (2004). "Cloud formation, Evolution and Destruction". The Origin of Stars. Imperial College Press. pp. 53–86. ISBN 978-1-86094-501-4. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Harpaz, 1994, p. 20 and whole book

- ^ Harpaz, 1994, pp. 173–78

- ^ Harpaz, 1994, pp. 111–18

- ^ Harpaz, 1994, pp. 189–210

- ^ Johansson, Sverker (27 July 2003). "The Solar FAQ". Talk.Origins Archive. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 11 August 2006.

- ^ Lerner, K. Lee; Lerner, Brenda Wilmoth (2006). "Environmental issues: essential primary sources". Thomson Gale. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ Pogge, Richard W. (1997). "The Once & Future Sun". New Vistas in Astronomy. Archived from the original (lecture notes) on 27 May 2005. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ^ Bell III, J. F.; Campbell, B.A.; Robinson, M.S. (2004). Remote Sensing for the Earth Sciences: Manual of Remote Sensing (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. Archived from the original on 11 August 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ Montmerle, Thierry; Augereau, Jean-Charles; Chaussidon, Marc; et al. (2006). "Solar System Formation and Early Evolution: the First 100 Million Years". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 98 (1–4): 39–95. Bibcode:2006EM&P...98...39M. doi:10.1007/s11038-006-9087-5. S2CID 120504344.

- ^ Montmerle, 2006, pp. 87–90

- ^ Beatty, J.K.; Petersen, C.C.; Chaikin, A., eds. (1999). The New Solar System (4th ed.). Cambridge press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-521-64587-4. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ "Astrochemistry". www.cfa.harvard.edu/. 15 July 2013. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ Merriam Webster Dictionary entry "Exobiology" Archived 4 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 11 April 2013)

- ^ "About Astrobiology". NASA Astrobiology Institute. NASA. 21 January 2008. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- ^ "Astrobiology". University College London. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- ^ "Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres". Journal: Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ "Release of the First Roadmap for European Astrobiology". European Science Foundation. Astrobiology Web. 29 March 2016. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ Corum, Jonathan (18 December 2015). "Mapping Saturn's Moons". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ Cockell, Charles S. (4 October 2012). "How the search for aliens can help sustain life on Earth". CNN News. Archived from the original on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ Aveni, Anthony F. (1995). "Frombork 1992: Where Worlds and Disciplines Collide". Archaeoastronomy: Supplement to the Journal for the History of Astronomy. 26 (20): S74 – S79. Bibcode:1995JHAS...26...74A. doi:10.1177/002182869502602007. S2CID 220911940.

- ^ Hilbe, Joseph M. (2017). "Astrostatistics". Wiley Stats Ref: Statistics Reference Online. Wiley. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1002/9781118445112.stat07961. ISBN 978-1118445112.

- ^ Ouellette, Jennifer (13 May 2016). "Scientists Used the Stars to Confirm When a Famous Sapphic Poem Was Written". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ Ash, Summer (17 April 2018). "'Forensic Astronomy' Reveals the Secrets of an Iconic Ansel Adams Photo". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ Marché, Jordan D. (2005). "Epilogue". Theaters of Time and Space: American Planetaria, 1930–1970. Rutgers University Press. pp. 170–178. ISBN 0-813-53576-X. JSTOR j.ctt5hjd29.14.

- ^ Mims III, Forrest M. (1999). "Amateur Science—Strong Tradition, Bright Future". Science. 284 (5411): 55–56. Bibcode:1999Sci...284...55M. doi:10.1126/science.284.5411.55. S2CID 162370774.

Astronomy has traditionally been among the most fertile fields for serious amateurs [...]

- ^ "The American Meteor Society". Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2006.

- ^ Lodriguss, Jerry. "Catching the Light: Astrophotography". Archived from the original on 1 September 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2006.

- ^ Imbriale, William A. (July 1998). "Introduction to "Electrical Disturbances Apparently of Extraterrestrial Origin"". Proceedings of the IEEE. 86 (7): 1507–1509. doi:10.1109/JPROC.1998.681377.

- ^ Ghigo, F. (7 February 2006). "Karl Jansky and the Discovery of Cosmic Radio Waves". National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Archived from the original on 31 August 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2006.

- ^ "Cambridge Amateur Radio Astronomers". Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2006.

- ^ "The International Occultation Timing Association". Archived from the original on 21 August 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2006.

- ^ "Edgar Wilson Award". IAU Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. Archived from the original on 24 October 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ "American Association of Variable Star Observers". AAVSO. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ^ "11 Physics Questions for the New Century". Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 3 February 2006. Retrieved 12 August 2006.

- ^ Hinshaw, Gary (15 December 2005). "What is the Ultimate Fate of the Universe?". NASA WMAP. Archived from the original on 29 May 2007. Retrieved 28 May 2007.

- ^ Howk, J. Christopher; Lehner, Nicolas; Fields, Brian D.; Mathews, Grant J. (6 September 2012). "Observation of interstellar lithium in the low-metallicity Small Magellanic Cloud". Nature. 489 (7414): 121–23. arXiv:1207.3081. Bibcode:2012Natur.489..121H. doi:10.1038/nature11407. PMID 22955622. S2CID 205230254.

- ^ Beer, M. E.; King, A. R.; Livio, M.; Pringle, J. E. (November 2004). "How special is the Solar system?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 354 (3): 763–768. arXiv:astro-ph/0407476. Bibcode:2004MNRAS.354..763B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.08237.x. S2CID 119552423.

- ^ Kroupa, Pavel (2002). "The Initial Mass Function of Stars: Evidence for Uniformity in Variable Systems". Science. 295 (5552): 82–91. arXiv:astro-ph/0201098. Bibcode:2002Sci...295...82K. doi:10.1126/science.1067524. PMID 11778039. S2CID 14084249.

- ^ "FAQ – How did galaxies form?". NASA. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ "Supermassive Black Hole". Swinburne University. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ Hillas, A.M. (September 1984). "The Origin of Ultra-High-Energy Cosmic Rays". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 22: 425–44. Bibcode:1984ARA&A..22..425H. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.22.090184.002233.

This poses a challenge to these models, because [...]

- ^ "Rare Earth: Complex Life Elsewhere in the Universe?". Astrobiology Magazine. 15 July 2002. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2006.

- ^ Sagan, Carl. "The Quest for Extraterrestrial Intelligence". Cosmic Search Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 August 2006. Retrieved 12 August 2006.

Sources

[edit]- Forbes, George (1909). History of Astronomy. London: Plain Label Books. ISBN 978-1-60303-159-2. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Harpaz, Amos (1994). Stellar Evolution. A K Peters. ISBN 978-1-56881-012-6.

- Unsöld, A.; Baschek, B. (2001). The New Cosmos: An Introduction to Astronomy and Astrophysics. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-67877-9.

External links

[edit]- NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED) (NED-Distances)

- Core books and Core journals in Astronomy, from the Smithsonian/NASA Astrophysics Data System

KSF

KSF