Auschwitz bombing debate

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 29 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 29 min

The issue of why the Allies did not act on early reports of atrocities in the Auschwitz concentration camp by destroying it or its railways by air during World War II has been a subject of controversy since the late 1970s. Brought to public attention by a 1978 article from historian David Wyman, it has been described by Michael Berenbaum as "a moral question emblematic of the Allied response to the plight of the Jews during the Holocaust",[1] and whether or not the Allies had the requisite knowledge and the technical capability to act continues to be explored by historians. The U.S. government followed the military's strong advice to always keep the defeat of Germany the paramount objective, and refused to tolerate outside civilian advice regarding alternative military operations. No major American Jewish organizations recommended bombing.

Background

[edit]Allied intelligence on the Holocaust

[edit]-

German concentration camps: Auschwitz, Oranienburg, Mauthausen and Dachau in "The Polish White Book", New York (1941).

-

Halina Krahelska report from Auschwitz Oświęcim, pamiętnik więźnia ("Auschwitz: Diary of a prisoner"), 1942.

-

"The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland", a paper issued by the Polish government-in-exile addressed to the United Nations, 1942

In 1942, Lieutenant Jan Karski reported to the Polish, British and U.S. governments on the situation in occupied Poland, especially the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto and the general systematic extermination of the Poles and Jews nationally. He did not know about the murder by gas, repeating the common belief at the time that deported Jews were being exterminated with electricity.[2] Karski met with the Polish government-in-exile, including the Prime Minister, Władysław Sikorski, as well as with members of political parties such as the Socialist Party, National Party, Labor Party, People's Party, Jewish Labour Bund and Zionist Party. He also spoke to Anthony Eden, the British Foreign Secretary, and included a detailed statement on what he had seen in Warsaw and in Bełżec. In 1943 in London he met the author and journalist Arthur Koestler. He then traveled to the United States and reported to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. FDR reacted to Karski's report by inquiring jokingly into animal rights abuses (specifically, horses). His report was a major source of information for the Allies.[3]

The Polish Government—as the representatives of the legitimate authority on territories in which the Germans are carrying out the systematic extermination of Polish citizens and of citizens of Jewish origin of many other European countries—consider it their duty to address themselves to the Governments of the United Nations, in the confident belief that they will share their opinion as to the necessity not only of condemning the crimes committed by the Germans and punishing the criminals, but also of finding means offering the hope that Germany might be effectively restrained from continuing to apply her methods of mass extermination.

Karski met also with many other government and civic leaders in the United States, including Felix Frankfurter, Cordell Hull, William Joseph Donovan, and Stephen Wise. Karski presented his report to media, to bishops of various denominations (including Cardinal Samuel Stritch), to members of the Hollywood film industry and artists, but without success. Many of those he spoke to did not believe him, or judged his testimony much exaggerated or saw it as propaganda from the Polish government in exile.[5]

| Part of a series on |

| The Holocaust |

|---|

|

In 1942, members of the Polish government in exile launched an official protest against systematic murders of Poles and Jews in occupied Poland, based on Karski's report. The Poles addressed their protest to the 26 Allies who had signed the Declaration by United Nations on January 1, 1942.[6][7]

In response, the Allied Powers issued an official statement on December 17, 1942, condemning the known German atrocities.[6] The statement was read to the British House of Commons in a debate led by the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, and published on the front page of The New York Times[8] and by many other newspapers such as The Times.[9] At the end of the debate the House of Commons stood for a minute in silence.[10] Eden commented that:

Jews are being transported, in conditions of appalling horror and brutality, to Eastern Europe. In Poland, which has been made the principal Nazi slaughterhouse, the ghettoes established by the German invaders are being systematically emptied of all Jews except a few highly skilled workers required for war industries. None of those taken away are ever heard of again. The able-bodied are slowly worked to death in labour camps. The infirm are left to die of exposure and starvation or are deliberately massacred in mass executions. The number of victims of these bloody cruelties is reckoned in many hundreds of thousands of entirely innocent men, women and children. ... So far as the responsibility is concerned, I would certainly say it is the intention that all persons who can properly be held responsible for these crimes, whether they are the ringleaders or the actual perpetrators of the outrages, should be treated alike, and brought to book.

On December 13, 1942, the Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom Joseph Hertz ordained a day of mourning to mark the suffering of "the numberless victims of the Satanic carnage". The Archbishop of Canterbury, William Temple, wrote a letter to The Times to condemn "a horror beyond what imagination can grasp". These responses were mentioned in BBC Radio broadcasts to Europe in several languages that were made on December 17.[11]

In 1942, Szmul Zygielbojm, a Jewish-Polish socialist politician, leader of the General Jewish Labor Bund in Poland, and member of the National Council of the Polish government in exile, wrote in English a booklet titled Stop Them Now. German Mass Murder of Jews in Poland, with a foreword by Lord Wedgwood.[12]

From April 19, 1943, through April 30, 1943, during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of April 19 to May 16, representatives of the governments of the United Kingdom and the United States held an international conference at Hamilton, Bermuda. They discussed the question of Jewish refugees who had been liberated by Allied forces and of those who still remained in Nazi-occupied Europe. The only agreement made was that the war against the Nazis must be won. The US did not raise its immigration quotas and the British prohibition on Jewish refugees seeking refuge in the British Mandate of Palestine remained in place until mid-1943. A week later, the American Zionist Committee for a Jewish Army ran an advertisement in The New York Times condemning the United States efforts at Bermuda as a mockery of past promises to the Jewish people and of Jewish suffering under German Nazi occupation.[13] Szmul Zygielbojm, a member of the Jewish advisory body to the Polish government-in-exile, committed suicide in protest.[5]

Allied intelligence on Auschwitz-Birkenau

[edit]

From April 1942 to February 1943, British Intelligence intercepted and decoded radio messages sent by the German Order Police, which included daily prisoner returns and death tolls for ten concentration camps, including Auschwitz.[14][15]

The United States Office of Strategic Services (the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and which had been established in 1941–1942 to coordinate intelligence and espionage activities in enemy territory) received reports about Auschwitz during 1942.[16][17]

Auschwitz prisoners reports

[edit]The Polish underground reports

[edit]At the beginning of Operation Reinhard, the principal source of intelligence for the Western Allies about the existence of Auschwitz was the Witold's Report, forwarded via the Polish resistance to the British government in London. It was written by the Polish Army Captain Witold Pilecki who spent a total of 945 days at the camp – the only known person to volunteer to be imprisoned at Auschwitz. He forwarded his report about the camp to Polish resistance headquarters in Warsaw through the underground network known as Związek Organizacji Wojskowej which he organized inside Auschwitz.[18] Pilecki hoped that either the Allies would drop weapons for the Armia Krajowa (AK) to organize an assault on the camp from the outside, or bring in the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade troops to liberate it. A spectacular escape took place on June 20, 1942, when Kazimierz Piechowski (prisoner no. 918) organized a daring passing through the camp's gate along with three friends and co-conspirators, Stanisław Gustaw Jaster, Józef Lempart and Eugeniusz Bendera.[19] The escapees were dressed in stolen uniforms as members of the SS-Totenkopfverbände, fully armed and in an SS staff car. They drove out the main gate in a stolen Steyr 120 with a smuggled first report from Pilecki to Polish resistance. The Germans never recaptured any of them.[20] By 1943 however, Pilecki realized that no rescue plans existed in the West. He escaped from the camp on the night of April 26–27, 1943.[21]

The first written accounts of Auschwitz concentration camp were published in 1940/41 in the Polish underground newspapers Polska żyje ("Poland lives") and Biuletyn Informacyjny.[22] From 1942 members of the Bureau of Information and Propaganda of the Warsaw Area Home Army also began to publish short booklets based on the experiences of escapees. The first was the fictional Auschwitz: Memories of a Prisoner written by Halina Krahelska and published in April 1942 in Warsaw.[23] The second publication was also produced in 1942 in the PPS WRN book Obóz śmierci ("Camp of Death") written by Natalia Zarembina.[24] In the summer of 1942 a book about Auschwitz titled W piekle ("In Hell") was written by the Polish writer, social activist and founder of Żegota, Zofia Kossak-Szczucka[25]

Polish reports about Auschwitz were also published in English versions. A booklet titled Zarembina was translated into English and published by the Polish Labor Group in New York in March 1944 with the title "Oswiecim, Camp of Death (Underground Report)" with a foreword by Florence Jaffray Harriman. In this report from 1942, the gassing of prisoners was described.[26]

Auschwitz site plans, originating from the Polish government, were passed on to the British Foreign Office on August 18, 1944.[27] Władysław Bartoszewski, himself a former Auschwitz inmate (camp number 4427), said in a speech: "The Polish resistance movement kept informing and alerting the free world to the situation. In the last quarter of 1942, thanks to the Polish emissary Jan Karski and his mission, and also by other means, the Governments of the United Kingdom and of the United States were well informed about what was going on in Auschwitz-Birkenau."[28]

The Jewish escapees' reports

[edit]On April 7, 1944, two young Jewish inmates, Rudolf Vrba and Alfréd Wetzler, had escaped from the Auschwitz camp with detailed information about the camp's geography, the gas chambers, and the numbers being killed. The information, later called the Vrba-Wetzler report, is believed to have reached the Jewish community in Budapest by April 27. Roswell McClelland, the U.S. War Refugee Board representative in Switzerland, is known to have received a copy by mid-June, and sent it to the board's executive director on June 16, according to Raul Hilberg.[29] Information based on the report was broadcast on June 15 by the BBC and on June 20 by The New York Times. The full report was first published on November 25, 1944, by the U.S. War Refugee Board, the same day that the last 13 prisoners, all women, were killed in Auschwitz (the women were unmittelbar getötet—killed immediately—leaving open whether they were gassed or otherwise killed).[30]

Allied reconnaissance and bombing missions

[edit]

Auschwitz was first overflown by an Allied reconnaissance aircraft on April 4, 1944, in a mission to photograph the synthetic oil plant at Monowitz forced labor camp (Auschwitz III).[31]

On June 26, seventy-one B-17 heavy bombers on another bombing run had flown above or close to three railway lines to Auschwitz.[32]

On July 7, shortly after the U.S. War Department refused requests from Jewish leaders to bomb the railway lines leading to the camps, 452 bombers of the Fifteenth Air Force flew along and across the five deportation railway lines on their way to bomb Blechhammer oil refineries nearby.[33]

Buna-Werke, the I.G. Farben industrial complex adjacent to the Monowitz forced labor camp (Auschwitz III) located 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) from the Auschwitz I camp, was bombed four times between August 20, 1944, and December 26, 1944.[34] On December 26, the U.S. 455th Bomb Group bombed Monowitz and targets near Birkenau (Auschwitz II); an SS military hospital was hit and five SS personnel were killed.[35]

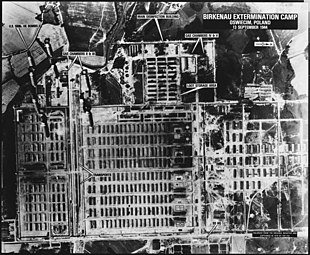

The Auschwitz complex was photographed accidentally several times during missions aimed at nearby military targets.[36] However, the photo-analysts knew nothing of Auschwitz, and the political and military hierarchy did not know that photos of Auschwitz existed.[37] For this reason, the photos played no part in the decision whether or not to bomb Auschwitz.[37] Photo-interpretation expert Dino Brugioni believes that analysts could have easily identified the important buildings in the complex if they had been asked to look.[37]

Chances of success

[edit]The issue of bombing Auschwitz-Birkenau first attracted wide public attention in May 1978 with the publication in Commentary of the article "Why Auschwitz Was Never Bombed" by historian David S. Wyman (subsequently incorporated into his 1984 New York Times bestseller, The Abandonment of the Jews).[38] Since then, several studies have explored the question of whether the Allies had the requisite knowledge and technical capability to bomb the killing facilities at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

In 2000, the edited collection The Bombing of Auschwitz: Should the Allies Have Attempted It? appeared. In the introduction, editor Michael Neufeld wrote: "As David Wyman was able to show at the outset, it is impossible to claim that Auschwitz-Birkenau could not have been bombed. In fact, the Fifteenth Air Force did drop bombs on it by accident on 13 September 1944, when SS barracks were hit by bombs falling short of their intended industrial targets. The question rather becomes one of the likelihood of hitting the four main gas chamber/crematoria complexes along the west side of Birkenau, and the likelihood that bombs would have fallen in profusion on the rows and rows of adjacent prisoner barracks. Accuracy is thus the central issue".[39]

Submitted proposals to bomb Auschwitz and reactions

[edit]The first proposal to bomb Auschwitz was made on May 16, 1944, by a Slovak rabbi, Michael Dov Weissmandl, a leader in an underground Slovak organization known as the Working Group to the Jewish Agency. According to Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer, Weissmandl's proposal is the basis of subsequent proposals.[40] At about the same time, two officials of the Jewish Agency in Palestine separately made similar suggestions. Yitzhak Gruenbaum made his to the U.S. Consul-General in Jerusalem, Lowell C. Pinkerton, and Moshe Shertok made his to George Hall, the British under secretary of state for foreign affairs. However, the idea was promptly squashed by the Executive Board of the Jewish Agency. On June 11, 1944, the Executive of the Jewish Agency considered the proposal, with David Ben-Gurion in the chair, and it specifically opposed the bombing of Auschwitz. Ben Gurion summed up the results of the discussion: "The view of the board is that we should not ask the Allies to bomb places where there are Jews."[41]

In the meantime, George Mantello distributed the Auschwitz Protocols (including the Vrba–Wetzler report) and triggered a significant grass roots protest in Switzerland, including Sunday masses, street protests and the Swiss Press Campaign. On June 19, 1944 the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem received the reports summary. David Ben-Gurion and the Jewish Agency had reversed its opposition immediately upon learning that Auschwitz was indeed a death camp, and urged U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to bomb the camp and the train tracks leading to the camp.[42]

Shortly thereafter, Benjamin Akzin, a junior official on the War Refugee Board staff made a similar recommendation. It was put in writing in an inter-office memorandum dated June 29 to his superior, a senior staff member, Lawrence S. Lesser. These recommendations were totally rejected by leading Jewish organizations. On June 28, Lesser met with A. Leon Kubowitzki, the head of the Rescue Department of the World Jewish Congress, who flatly opposed the idea. On July 1, Kubowitzki followed up with a letter to War Refugee Board Director John W. Pehle, recalling his conversation with Lesser and stating:

The destruction of the death installations can not be done by bombing from the air, as the first victims would be the Jews who are gathered in these camps, and such a bombing would be a welcome pretext for the Germans to assert that their Jewish victims have been massacred not by their killers, but by the Allied bombers.

The American reactions

[edit]In June 1944, John Pehle of the War Refugee Board and Benjamin Akzin, a Zionist activist in America, urged the United States Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy to bomb the camps. McCloy told his assistant to "kill" the request,[43] as the United States Army Air Forces had decided in February 1944 not to bomb anything "for the purposes of rescuing victims of enemy oppression", but to concentrate on military targets.[44] However, Rubinstein says that Akzin was not involved in discussions between Pehle and McCloy, and that Pehle specifically told McCloy that he was transmitting an idea proposed by others, that he had "several doubts about the matter", and that he was not "at this point at least, requesting the War Department to take any action on this proposal other than to appropriately explore it".[41]

On August 2, General Carl Andrew Spaatz, commander of the United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe, expressed sympathy for the idea of bombing Auschwitz.[45] Several times thereafter, in the summer and early autumn of 1944, the War Refugee Board relayed to the War Department suggestions by others that Auschwitz and/or the rail lines could be bombed. It repeatedly noted that it was not endorsing anything. On October 4, 1944, the War Department sent (and only this time) a rescue-oriented bombing proposal to General Spaatz in England for consideration. Although Spaatz's officers had read Mann's message reporting acceleration of extermination activities in the camps in Poland, they could perceive no advantage to the victims in smashing the killing machinery, and decided not to bomb Auschwitz. Nor did they seem to understand, despite Mann's statement that "the Germans are increasing their extermination activities", that wholesale massacres had already been perpetrated.[46]

Finally, on November 8, 1944, having half-heartedly changed sides, Pehle ordered McCloy to bomb the camp. He said it could help some of the inmates to escape and would be good for the "morale of underground groups". According to Kai Bird, Nahum Goldmann apparently also changed his mind. Sometime in the autumn of 1944, Goldmann went to see McCloy in his Pentagon office and personally raised the bombing issue with him. However, by November 1944, Auschwitz was more or less completely shut down.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, sensitive to the importance of his Jewish constituency, consulted with Jewish leaders. He followed their advice to not emphasize the Holocaust for fear of inciting anti-semitism in the U.S. Historians Richard Breitman and Allan J. Lichtman argue that after Pearl Harbor:

Roosevelt and his military and diplomatic advisers sought to unite the nation and blunt Nazi propaganda by avoiding the appearance of fighting a war for the Jews. They tolerated no potentially divisive initiatives or any diversion from their campaign to win the war as quickly and decisively as possible. ... Success on the battlefield, Roosevelt and his advisers believed, was the only sure way to save the surviving Jews of Europe.[47]

Breitman and Lichtman also argue:

Roosevelt played no apparent role in the decision not to bomb Auschwitz. Even if the matter had reached his desk, however, he would not likely have contravened his military. Every major American Jewish leader and organization that he respected remained silent on the matter, as did all influential members of Congress and opinion-makers in the mainstream media.[48]

The British reactions

[edit]The British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, did not see bombing as a solution, given that bombers were inaccurate and would also kill prisoners on the ground. The land war would have to be won first. Bombers were used against German cities and to carpet-bomb the front lines.[citation needed] According to Martin Gilbert,[31] Churchill pushed for bombing. Concerning the concentration camps, he wrote to his Foreign Secretary on July 11, 1944: "all concerned in this crime who may fall into our hands, including the people who only obeyed orders by carrying out these butcheries, should be put to death".[49] The British Air Ministry was asked to examine the feasibility of bombing the camps and decided not to for "operational reasons", which were not specified in wartime. In August 1944, 60 tons of supplies were flown to assist the uprising in Warsaw and, considering the dropping accuracy at that time, were to be dropped "into the south-west quarter of Warsaw". For various reasons, only seven aircraft reached the city.[50]

Post-war analysis

[edit]Michael Berenbaum has argued that it is not only a historical question, but "a moral question emblematic of the Allied response to the plight of the Jews during the Holocaust".[1] David Wyman has asked: "How could it be that the governments of the two great Western democracies knew that a place existed where 2,000 helpless human beings could be killed every 30 minutes, knew that such killings actually did occur over and over again, and yet did not feel driven to search for some way to wipe such a scourge from the earth?"[51] Kevin Mahoney, in an analysis of three requests submitted to the allies to bombard railway lines leading to Auschwitz, concludes that:

The fate of the three requests to the MAAF in late August and early September 1944 dramatically illustrates why all proposals to bomb the rail facilities used to deport the Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz during 1944, as well as to bomb the camp itself, failed. None was able to outweigh overriding military aims in pursuit of final victory over the Germans.[52]

See also

[edit]- The Abandonment of the Jews

- Functionalism–intentionalism debate

- History of the Jews in Hungary

- International response to the Holocaust

- Operation Jericho

- Outside support during the Warsaw Uprising

- Witold's Report

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Berenbaum, Michael. "Why wasn't Auschwitz bombed?" Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Joel Zisenwine (2013). "British Intelligence and information about murder by gas – A reappraisal". Yad Vashem Studies. 41 (1): 151–186.[page needed]

- ^ Władysław Bartoszewski (January 27, 2005), Address by the former Foreign Minister of Poland at the ceremony of the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau. [dead link] InternationalePolitik.de, pp. 156–157 in PDF.

- ^ Polish Government in Exile, "The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland – note addressed to the Governments of the United Nations on December 10th, 1942". London, New York, Melbourne, 1942, p. 10.

- ^ a b E. Thomas Wood and Stanislaw M. Jankowski (1994), Believing the Unbelievable, Karski: How One Man Tried to Stop the Holocaust

- ^ a b Engel (2014)

- ^ Republic of Poland, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1942). The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland. London: Hutchinson and Company. OCLC 23800633. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ^ "11 Allies Condemn Nazi War on Jews". The New York Times. December 18, 1942. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ "Barbarity to Jews: Retribution by Allies: Commons endorse a pledge". The Times, December 18, 1942.

- ^ "JEWS (GERMAN BARBARITIES) United Nations Declaration". Hansard, HC Deb 17 December 1942 vol 385 cc. 2082–87. Accessed September 13, 2019.

- ^ "On This Day, 17 December 1942: Britain condemns massacre of Jews". BBC News. Accessed December 15, 2022.

- ^ Szmul Zygielbojm (1942), "Stop Them Now. German Mass Murder of Jews in Poland", London: Liberty Publications.

- ^ "To 5,000,000 Jews in the Nazi Death-Trap Bermuda was a Cruel Mockery", The New York Times, May 4, 1943, p. 17.

- ^ "Daily proforma returns contained in GPCC series monthly reports, for ten concentration camps". Kew, London: The National Archives. 1942–1943.

1942–1943 Daily proforma returns contained in GPCC [German Police Concentration Camp] series monthly reports, for ten concentration camps, including Auschwitz, Buchenwald and Dachau, include daily intakes and deaths, with inmate totals listed by nationality headed by Jews

- ^ "Bletchley Park Concentration Camp Decodes". WhatRreallyHhappend.INFO. 1942–1943.

These decoded 'German Police Concentration Camp' or GPCC HORHUG figures, described as the concentration camp 'vital statistics', contained totals for the inmate populations at several concentration camps, including Dachau, Auschwitz and Buchenwald. ... GC and CS interpreted column (c) – 'departures by any means' – as being accounted for primarily by deaths. The returns from Auschwitz, the largest of the camps with 20,000 prisoners, mentioned illness as the main cause of death, but included references to shootings and hangings. There were no references in the decrypts to gassing.

- ^ "O.S.S. records RG 226, COI/OSS Central Files 1942–1946 (Entry 92): Report from Poland on German Concentration Camp at Auschwitz Sept. 1942". U.S. National Archives. 1942.

- ^ "O.S.S. records RG 226, Entry 210 – Reports prepared by Dr. Alexander S. Lipsett, June–August 1942". National Archives and Records Administration.

Information on Poland, with statement that 'over 3,000 prisoners have died in the Polish concentration camp at Oswiecim [Auschwitz] during the past eight months'

[permanent dead link] - ^ Jozef Garlinski, Fighting Auschwitz: the Resistance Movement in the Concentration Camp, Fawcett, 1975, ISBN 0-449-22599-2, reprinted by Time Life Education, 1993. ISBN 0-8094-8925-2

- ^ Kazimierz Piechowski, Eugenia Bozena Kodecka-Kaczynska, Michal Ziokowski, Byłem Numerem: swiadectwa z Auschwitz. Wydawn. Siostr Loretanek, hardcover, ISBN 83-7257-122-8.[page needed]

- ^ Gabriela Nikliborc (January 13, 2009). "Auschwitz-Birkenau – The Film about the Amazing Escape from Auschwitz – Now Available on DVD". En.auschwitz.org.pl. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

Uciekinier [The Escapee] directed and written by Marek Tomasz Pawłowski for Telewizja Polska; 56 minutes. Poland 2007.

- ^ Cyra, Adam; Pilecki, Witold (2000). "II". Ochotnik do Auschwitz; Witold Pilecki (1901–1948). Oświęcim: Chrześcijańskie Stowarzyszenie Rodzin Oświęcimskich. ISBN 978-83-912000-3-2.

- ^ Władysław Bartoszewski, "Warszawski pierścień śmierci 1939–1944", Zachodnia Agencja Prasowa, Warsaw 1967, Interpress, Warsaw 1970, Świat Książki, Warsaw 2008, ISBN 978-83-247-1242-7. Published also in English in 1968.

- ^ Halina Krahelska, Oświęcim. Pamiętnik więźnia, BIP Okręgu Warszawskiego AK (Bureau of Information and Propaganda of Warsaw Area Home Army), Warsaw 1942.

- ^ Natalia Zarembina, Obóz śmierci, Wydawnictwo WRN, Warsaw 1942.

- ^ Zofia Kossak-Szczucka, W piekle, Front Odrodzenia Polski, Warszawa 1942.

- ^ "Oswiecim, Camp of Death (Underground Report)"

- ^ "A letter to the U.K. foreign office, with plans of Auschwitz". August 18, 1944.

- ^ Address by the former Foreign Minister of Poland Wladysław Bartoszewski at the ceremony of the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, 27 January 2005 [dead link] see pp. 156–157

- ^ Hilberg, Raul. The Destruction of the European Jews, Yale University Press, 2003, p. 1215.

- ^ Czech, Danuta (ed.). Kalendarium der Ereignisse im Konzentrationslager Auschwitz-Birkenau 1939–1945, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 1989, pp.920 and 933, using information from a series called Hefte von Auschwitz, and cited in Karny, Miroslav. "The Vrba and Wetzler report", in Berenbaum, Michael & Gutman, Yisrael (eds.). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp, p. 564, Indiana University Press and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 1994.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Martin (January 27, 2005). "Could Britain have done more to stop the horrors of Auschwitz?" The Times. Accessed December 15, 2022.

- ^ Marrus, Michael Robert (January 1, 1989). The End of the Holocaust. Walter de Gruyter. p. 319. ISBN 978-3-11-097651-9.[verification needed]

- ^ Gutman, Yisrael; Berenbaum, Michael; Wyman, David (January 1, 1998). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Indiana University Press. p. 577. ISBN 978-0-253-20884-2.

In May, General Ira C. Eaker, commander of Allied air forces in Italy, pointed out that strikes on Blechhammer could be carried out simultaneously with attacks on war industries at Auschwitz and Odertal. By May 1944, the 15th Air Force had turned its primary attention to oil targets. ... the close attention paid to oil in 1944 and 1945 was one of the most decisive factors in Germany's defeat. ... In late June, the 15th Air Force was about to move the oil war [into upper Silesia], ... Eight important oil plants were clustered within a rough half-circle 35 miles in radius, with Auschwitz near the northeast end of the arc and Blechhammer near the northwest end. Blechhammer was the main target. Fleets ranging from 102 to 357 heavy bombers hit it on ten occasions between July 7 and November 20. But Blechhammer was not the only industrial target. All eight plants shook under the impact of tons of high explosives. Among them was the industrial section of Auschwitz itself.

- ^ Gutman, Yisrael; Berenbaum, Michael; Wyman, David (January 1, 1998). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Indiana University Press. p. 578. ISBN 978-0-253-20884-2.

Late in the morning on Sunday. August 20. 127 Flying Fortresses, escorted by 100 Mustang fighters, dropped 1,336 500-pound high-explosive bombs on the factory areas of Auschwitz, less than five miles east of the gas chambers. The weather was excellent ... ideal for accurate visual bombing. Antiaircraft fire and the 19 German fighter planes there were ineffective. Only one U.S. bomber went down; no Mustangs were hit.

- ^ "Auschwitz through the lens of the SS: Photos of Nazi leadership at the camp". Archived October 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dino Brugioni and Robert Poirier, The Holocaust revisited: A retrospective analysis of the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination complex; CIA report 1978 Archived May 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c Dino Brugioni (January–March 1983), "Auschwitz and Birkenau: Why the World War II photo interpreters failed to Identify the extermination complex", Military Intelligence, vol. 9, no. 1: pp. 50–55.

- ^ Wyman, David S. (May 1978). "Why Auschwitz Was Never Bombed". Commentary (65): 37–46.

- ^ Michael J. Neufeld and Michael Berenbaum, eds. (2000). The Bombing of Auschwitz: Should the Allies Have Attempted it?. New York: St. Martin’s Press, p. 7.

- ^ Bauer 2002, p. 234.

- ^ a b William D. Rubinstein, The Myth of Rescue, London, Routledge 1997, especially Chapter 4, "The Myth of Bombing Auschwitz".

- ^ Shamir, Shlomo (October 12, 2009). "Study: Ben-Gurion changed his mind on Allied bombing of Auschwitz". Haaretz.

Relying on newly declassified documents from the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem, Medoff states that the Jewish Agency and Ben-Gurion had urged U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to bomb the camp and the train tracks leading to the camp after they had learned of the existence of the crematoriums and gas chambers. Medoff relies primarily on the minutes and protocols of Jewish Agency meetings in June 1944.

- ^ Gilbert, Martin (November 8, 1993). "Churchill and the Holocaust: The Possible and Impossible". Archived from the original on November 1, 2013.

when the request [to bomb Auschwitz] was put to the American Air Force Commander, General R. Eaker, when he visited the Air Ministry a few days later, he gave it his full support. He regarded it as something that the American daylight bombers could and should do

- ^ "The man who wanted to bomb Auschwitz". The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation.

- ^ Breitman, Richard; Lichtman, Allan J. (2013). FDR and the Jews. Harvard University Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-674-07365-4.

On August 2, general Carl Spaatz, commander of the U.S strategic air forces, expressed sympathy for the idea of bombing Auschwitz

- ^ Marrus, Michael Robert (January 1, 1989). The End of the Holocaust. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 316–320. ISBN 978-3-11-097651-9.

Anderson put an end to the proposal: 'I do not consider that the unfortunate Poles herded in these concentration camps would have their status improved by the destruction of the extermination chambers. There is also the possibility of some of the bombs landing on the prisoners as well, and in that event, the Germans would be provided with a fine alibi for any wholesale massacre that they might perpetrate. I therefore recommend that no encouragement be given to this project.' Although Spaatz's officers had read Mann's message reporting acceleration of extermination activities in the camps in Poland, they could perceive no advantage to the victims, in smashing the killing machinery.

[verification needed] - ^ Richard Breitman and Allan J. Lichtman (2013), FDR and the Jews, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Breitman and Lichtman, p. 321.

- ^ Churchill, Winston. Triumph and Tragedy. Penguin 2005, p. 597.

- ^ Churchill, 2005. pp. 115–117.

- ^ Wyman, David S. "Why Auschwitz wasn't bombed", in Gutman, Yisrael & Berenbaum, Michael. Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Indiana University Press, 1998, p. 583.

- ^ Mahoney, K. A. (December 1, 2011). "An American Operational Response to a Request to Bomb Rail Lines to Auschwitz". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 25 (3): 438–446. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcr049. ISSN 8756-6583. S2CID 144903891.

References

[edit]- Bauer, Yehuda (2002). Rethinking the Holocaust. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300093001.

- Berenbaum, Michael. "Why wasn't Auschwitz bombed?". Encyclopædia Britannica.[verification needed]

- Breitman, Richard; Lichtman, Allan J. (2013). FDR and the Jews. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-07365-4.

- Churchill, Winston (2005) [1953]. Triumph and Tragedy. Penguin.

- Hilberg, Raul (2003). The Destruction of the European Jews. Yale University Press.

- Wyman, David S. (1998) [1994]. "Why Auschwitz wasn't bombed". In Yisrael Gutman; Michael Berenbaum (eds.). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20884-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Beir, Robert L. (2013). Roosevelt and the Holocaust: How FDR saved the Jews and brought hope to a nation. Simon and Schuster.

- Neufield, Michael J. and Michael Berenbaum, eds. (2000) The Bombing of Auschwitz: Should the Allies Have Attempted It? St Martins Press.

- Engel, David (2014). In the Shadow of Auschwitz: The Polish Government-in-exile and the Jews, 1939–1942. UNC Press Books. ISBN 9781469619576.

- Erdheim, Stuart (1997). "Could the Allies Have Bombed Auschwitz-Birkenau?" Holocaust and Genocide Studies, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 129–170.

- Fleming, Michael (2014). Auschwitz, the Allies and Censorship of the Holocaust. Cambridge University Press.

- Fleming, Michael (2020). "The reassertion of the elusiveness narrative: Auschwitz and Holocaust knowledge". Holocaust Studies 26.4: 510–530.

- Foregger, Richard (1990). "Technical Analysis of Methods to Bomb the Gas Chambers at Auschwitz". Holocaust and Genocide Studies 5#4: 403–421.

- Foregger, Richard (October 1995). "Two Sketch Maps of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Extermination Camps". Journal of Military History 59#4: pp. 687–696.

- Friedman, Max Paul (Spring 2005). "The U.S. State Department and the Failure to Rescue: New Evidence on the Missed Opportunity at Bergen-Belsen". Holocaust and Genocide Studies 19#1: pp. 26–50.

- Gilbert, Martin (1981). Auschwitz and the Allies. New York: Holt, Rinehart, Winston. Part Three: Auschwitz Revealed.

- Groth, Alexander J. (2014). "Absolving the Allies? Another Look at the Anglo—American Response to the Holocaust". Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs 8.1: 115–130.

- Groth, Alexander J. (2012). "The Holocaust: America, and American Jewry Revisited". Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs. 6 (2): 137–141. doi:10.1080/23739770.2012.11446510. S2CID 147069959.

- Groth, Alexander J.; Medoff, Rafael; Cohen, Michael J. (2012). "When Did They Know and What Could They Have Done? More on the Allies' Response to the Holocaust". Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs. 7 (1).

- Kitchens, James H. (April 1994). "The Bombing of Auschwitz Re-examined". The Journal of Military History. 58 (2): 233–266. doi:10.2307/2944021. JSTOR 2944021.

- Levy, Richard H. (1996). "The Bombing of Auschwitz Revisited: A Critical Analysis". Holocaust and Genocide Studies 10.3: 267–298.

- Levy, Richard H., ed. (2000). The Bombing of Auschwitz Revisited: A Critical Analysis. St. Martins Press. pp. 101, et seq.

- Mahoney, Kevin A. (2011). "An American operational response to a request to bomb rail lines to Auschwitz". Holocaust and Genocide Studies 25.3: 438–446.

- Medoff, Rafael (1996). "New perspectives on how America, and American Jewry, responded to the Holocaust". American Jewish History 84.3: 253–266.

- Pomakoy, Keith (2011). Helping Humanity: American Policy and Genocide Rescue. Lexington Books.

- Orbach, D.; Solonin, M. (April 1, 2013). "Calculated Indifference: The Soviet Union and Requests to Bomb Auschwitz". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 27 (1): 90–113. doi:10.1093/hgs/dct002. ISSN 8756-6583. S2CID 144858061.

- Westermann, Edward B. (2001). "The Royal Air Force and the Bombing of Auschwitz: First Deliberations, January 1941". Holocaust and Genocide Studies 15.1: 70–85.

- White, Joseph Robert (2002). "Target auschwitz: Historical and hypothetical German responses to allied attack".[dead link] Holocaust and Genocide Studies 16.1: 54–76.

- Wyman, David S. (1984). The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust, 1941–1945. New York: Pantheon Books.

Bibliography

[edit]- Republic of Poland Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Polish Government-in-Exile (1941). German Occupation of Poland. Extract of Note Addressed to The Allied and Neutral Powers. Polish White Book. New York: The Greystone Press, Wydawnictwo 'RÓJ' in Exile.

- Authority of the Polish Ministry of Information (1942). The Black Book of Poland. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons.

External links

[edit]- "The Auschwitz Bombing Controversy in Context" – online lecture by Dr. David Silberklang of Yad Vashem

- "Why didn't the Allies bomb Auschwitz?" BBC News, 23 January 2005

KSF

KSF