Avestan

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

| Avestan | |

|---|---|

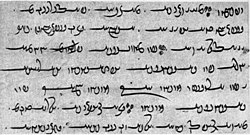

Yasna 28.1, Ahunavaiti Gatha (Bodleian MS J2) | |

| Region | Central Asia |

| Era | Late Bronze Age, Iron Age |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ae |

| ISO 639-2 | ave |

| ISO 639-3 | ave |

| Glottolog | aves1237 |

| Linguasphere | 58-ABA-a |

| Part of a series on |

| Zoroastrianism |

|---|

|

|

|

Avestan (/əˈvɛstən/ ə-VESS-tən)[1] is the liturgical language of Zoroastrianism.[2] It belongs to the Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family and was originally spoken during the Old Iranian period (c. 1500 – 400 BCE)[3][f 1] by the Iranians living in the eastern portion of Greater Iran.[4][5]

After Avestan became extinct, its religious texts were first transmitted orally until being collected and put into writing during the Sasanian period (c. 400 – 500 CE).[6] The extant material falls into two groups:[7] Old Avestan (c. 1500 – 900 BCE)[8] and Younger Avestan (c. 900 – 400 BCE).[9] The immediate ancestor of Old Avestan was the Proto-Iranian language, a sister language to the Proto-Indo-Aryan language, with both having developed from the earlier Proto-Indo-Iranian language.[10] As such, Old Avestan is quite close in both grammar and lexicon to Vedic Sanskrit, the oldest preserved Indo-Aryan language.[11]

Name

[edit]The Avestan texts consistently use the term Arya, i.e., Iranian, for the speakers of Avestan.[12] The same term also appears in ancient Persian and Greek sources as an umbrella term for Iranian languages.[13][14] Despite this, the Avestan texts never use Arya, or any other term, specifically in reference to the language itself and its native name therefore remains unknown.

The modern name Avestan is instead derived from the Avesta, which is the name of the written collection of the Avestan texts.[15] This collection was created during the Sasanian period to complement the, up to then, purely oral tradition. Like Vedic, Avestan is therefore a language which is named after the text corpus in which it is used and simply means language of the Avesta.[16] The name Avesta comes from Persian اوستا (avestâ) itself derived from Middle Persian abestāg. It might originate from a hypothetical Avestan term *upastāvaka (praise song). The language was sometimes called Zend in older works, stemming from a misunderstanding of the Zend (commentaries and interpretations of Zoroastrian scripture) as synonymous with the Avesta itself, due to both often being bundled together as Zend-Avesta.

Classification

[edit]Avestan is usually grouped into two variants: Old Avestan, also known as Gathic Avestan, and Young Avestan.[17] More recently, some scholars have argued for a third intermediate stage called Middle Avestan, but this is not yet universally followed.[18] Old Avestan is much more archaic than Young Avestan, especially in terms of its morphology. It is assumed that the two are separated by several centuries.[19] In addition, Old Avestan differs dialectally, i.e. it is not the direct predecessor of Young Avestan but a closely related dialect. Despite these differences, Old and Young Avestan are usually interpreted as two different variants of the same language instead of two different languages.[17][20][7]

Avestan is an Old Iranian language and, together with Old Persian, one of the two languages from that period for which longer texts are available.[21] Other known Old Iranian languages, like Median and early Scythian, are only known from isolated words and personal names. Young Avestan shows morphological and syntactical similarities with Old Persian, which may indicate that both were spoken around the same time.[9] On the other hand, Old Avestan is substantially more archaic than either of these and largely agrees morphologically with Vedic Sanskrit, i.e., the oldest known Indo-Aryan language.[22] This suggests that only a limited period of time has elapsed since the two separated from their common Indo-Iranian ancestor. The predecessor ancestor of Pashto was close to the language of the Gathas.[23]

Scholars traditionally classify Iranian languages as Eastern or Western according to certain grammatical features, and within this framework Avestan is sometimes classified as Eastern Old Iranian. However, as for instance Sims-Williams and Schmitt have pointed out, the east–west distinction is of limited meaning for Avestan, as the linguistic developments that later distinguish Eastern from Western Iranian had not yet occurred.[24][25] Due to some shared developments with Median, Scholars like Skjaervo and Windfuhr have classified Avestan as a Central Iranian language.[26]

History

[edit]Native Avestan

[edit]The Avestan language is only known from the Avesta and otherwise unattested. As a result, there is no external evidence on which to base the time frame during which the Avestan language was natively spoken and all attempts have to rely on internal evidence. Such attempts were often linked to the life of Zarathustra, being the central figure of Zoroastrianism.[27] Zarathustra was traditionally based in the 6th century BC meaning that Old Avestan would have been spoken during the early Achaemenid period.[28] Given that a substantial time must have passed between Old Avestan and Young Avestan, the latter would have been spoken somewhere during the Hellenistic or the Parthian period of Iranian history.[29]

However, more recent scholarship has increasingly shifted to an earlier dating.[30][31][32] The literature presents a number of reasons for this shift, based on both the Old Avestan and the Young Avestan material. As regards Old Avestan, the Gathas show strong linguistic and cultural similarities with the Rigveda, which in turn is assumed to represent the second half of the second millennium BC.[11][33][34][35] As regards Young Avestan, texts like the Yashts and the Vendidad are situated in the eastern parts of Greater Iran and lack any discernible Persian or Median influence from Western Iran.[36] This is interpreted such that the bulk of this material, which has been produced several centuries after Zarathustra, must still predate the sixth century BC.[37][38][39] As a result, more recent scholarship often assumes that the major parts of the Young Avestan texts mainly reflect the first half of the first millennia BC,[40][41][9] whereas the Old Avestan texts of Zarathustra may have been composed around 1000 BC[42][43][44][45] or even as early as 1500 BC.[46][8][47]

It is not known at what point Avestan ceased to be a spoken language. Even the Young Avestan texts are still quite archaic and show no signs of evolving into a hypothetical Middle Iranian stage of development.[48] In addition, none of the known Middle Iranian languages are the successor of Avestan.[49] The Zend, i.e., the Middle Persian commentaries of the Avesta show that Avestan was no longer fully understood by the Zoroastrian commentators, indicating that it was no longer a living language by the late Sasanian period.

Geographical distribution

[edit]

There are no historical sources that connect Avestan or its native speakers with any specific region. In addition, the Old Avestan texts do not mention any places names that can be identified. On the other hand, the Younger Avestan texts contain a substantial number of geographical references that are known from later sources and therefore allow to delineate the geographical horizon that was known and important to the speakers of Younger Avestan. It is nowadays widely accepted that these place names are situated in the eastern parts of Greater Iran corresponding to the entirety of present-day Afghanistan and Tajikistan as well as parts of Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.[50] Avestan is therefore assumed to have been spoken somewhere within this large region, although its precise location cannot be further specified.[51]

Due to this geographical uncertainty, as well as the lack of any dateable historical events within the texts themselves, linking any given archeological culture with the speakers of Avestan has remained difficult. Among possible candidates, the Yaz culture has been named as likely.[52] This is due to the fact that it is connected with the southward spread of steppe-derived Iranic groups, the presence of farming practices consisted with the Young Avestan society and the lack of burial sites, indicating the Zoroastrian practice of open air excarnation.[53]

Liturgical Avestan

[edit]Both Old and Young Avestan texts are assumed to have been composed by their respective native speakers and were possibly updated and revised for an extended period of time. At two different times, however, they became fixed, purely liturgical, languages and were transmitted by an oral tradition.[54] Scholars like Kellens, Skjærvø and Hoffman have identified a number of distinct stages of this transmission and how they changed the Avestan during its use as the sacred language of Zoroastrianism.[55][56][57]

In the first stage, Old Avestan would have become the liturgical language of the early Zoroastrian community as described in the Young Avestan texts.[57] Karl Hoffmann for instance identifies changes introduced due to slow chanting, the insertion of Young Avestan phonetic features into the material, attempts at standardizations as well as other editorial changes.[58] The Young Avestan texts, however, were still produced, recomposed, and handed down during this time in a fluid oral tradition.[59]

In the next stage, the Young Avestan texts crystallized as well meaning that both the Young and Old Avestan texts became the fixed, liturgical literature of non-Avestan Zoroastrian communities.[60] The transmission of this literature largely took place in Western Iran as evidenced by alterations introduced by native Persian speakers.[61] In addition, different scholars have tried to identify other dialects that may have impacted the pronunciation of certain Avestan features during the transmission, possibly before they reached Persia.[21] Some Young Avestan texts, like the Vendidad, show ungrammatical features and may have been partly recomposed by non-Avestan speakers.[62]

The purely oral transmission came to an end during the 5th or 6th century CE, when the Avestan corpus was committed to written form. This was achieved through the creation of the Avestan alphabet resulting in the Sasanian Avesta.[63] Despite this, the post Sasanian written transmission saw a further deterioration of the Avestan texts. A large portion of the literature was lost after the 10th century BCE[64] and the surviving texts show signs of incorrect pronunciations and copying errors.[21]

Many phonetic features cannot be ascribed with certainty to a particular stage since there may be more than one possibility. Every phonetic form that can be ascribed to the Sasanian archetype on the basis of critical assessment of the manuscript evidence must have gone through the stages mentioned above so that "Old Avestan" and "Young Avestan" really mean no more than "Old Avestan and Young Avestan of the Sasanian period".[21]

Alphabet

[edit]

The script used for writing Avestan developed during the 3rd or 4th century AD. By then the language had been extinct for many centuries, and remained in use only as a liturgical language of the Avesta canon. As is still the case today, the liturgies were memorized by the priesthood and recited by rote.

The script devised to render Avestan was natively known as Din dabireh "religion writing". It has 53 distinct characters and is written right-to-left. Among the 53 characters are about 30 letters that are – through the addition of various loops and flourishes – variations of the 13 graphemes of the cursive Pahlavi script (i.e. "Book" Pahlavi) that is known from the post-Sasanian texts of Zoroastrian tradition. These symbols, like those of all the Pahlavi scripts, are in turn based on Aramaic script symbols. Avestan also incorporates several letters from other writing systems, most notably the vowels, which are mostly derived from Greek minuscules. A few letters were free inventions, as were also the symbols used for punctuation. Also, the Avestan alphabet has one letter that has no corresponding sound in the Avestan language; the character for /l/ (a sound that Avestan does not have) was added to write Pazend texts.

The Avestan script is alphabetic, and the large number of letters suggests that its design was due to the need to render the orally recited texts with high phonetic precision. The correct enunciation of the liturgies was (and still is) considered necessary for the prayers to be effective.

The Zoroastrians of India, who represent one of the largest surviving Zoroastrian communities worldwide, also transcribe Avestan in Brahmi-based scripts. This is a relatively recent development first seen in the c. 12th century texts of Neryosang Dhaval and other Parsi Sanskritist theologians of that era, which are roughly contemporary with the oldest surviving manuscripts in Avestan script. Today, Avestan is most commonly typeset in the Gujarati script (Gujarati being the traditional language of the Indian Zoroastrians). Some Avestan letters with no corresponding symbol are synthesized with additional diacritical marks, for example, the /z/ in zaraθuštra is written with j with a dot below.

Phonology

[edit]Avestan has retained voiced sibilants, and has fricative rather than aspirate series. There are various conventions for transliteration of the Avestan alphabet, the one adopted for this article being:

Vowels:

- a ā ə ə̄ e ē o ō å ą i ī u ū

Consonants:

- k g γ x xʷ č ǰ t d δ θ t̰ p b β f

- ŋ ŋʷ ṇ ń n m y w r s z š ṣ̌ ž h

The glides y and w are often transcribed as <ii> and <uu>. The letter transcribed <t̰> indicates an allophone of /t/ with no audible release at the end of a word and before certain obstruents.[65]

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post-alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal or alveolo-palatal |

Velar | Labiovelar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | ⟨m⟩ /m/ | ⟨n⟩ /n/ | ⟨ń⟩ /ɲ/ | ⟨ŋ⟩ /ŋ/ | ⟨ŋʷ⟩ /ŋʷ/ | |||||

| Plosive | voiceless | ⟨p⟩ /p/ | ⟨t⟩ /t/ | ⟨č⟩ /tʃ/ | ⟨k⟩ /k/ | |||||

| voiced | ⟨b⟩ /b/ | ⟨d⟩ /d/ | ⟨ǰ⟩ /dʒ/ | ⟨g⟩ /ɡ/ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | ⟨f⟩ /ɸ/ | ⟨θ⟩ /θ/ | ⟨s⟩ /s/ | ⟨š⟩ /ʃ/ | ⟨ṣ̌⟩ /ʂ/ | ⟨š́⟩ /ɕ/ | ⟨x⟩ /x/ | ⟨xʷ⟩ /xʷ/ | ⟨h⟩ /h/ |

| voiced | ⟨β⟩ /β/ | ⟨δ⟩ /ð/ | ⟨z⟩ /z/ | ⟨ž⟩ /ʒ/ | ⟨γ⟩ /ɣ/ | |||||

| Approximant | ⟨y⟩ /j/ | ⟨v⟩ /w/ | ||||||||

| Trill | ⟨r⟩ /r/ | |||||||||

According to Beekes, [ð] and [ɣ] are allophones of /θ/ and /x/ respectively (in Old Avestan).

Vowels

[edit]| Front | Central | Back | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | ||

| Close | i ⟨i⟩ | iː ⟨ī⟩ | u ⟨u⟩ | uː ⟨ū⟩ | |||

| Mid | e ⟨e⟩ | eː ⟨ē⟩ | ə ⟨ə⟩ | əː ⟨ə̄⟩ | o ⟨o⟩ | oː ⟨ō⟩ | |

| Open | a ⟨a⟩ | aː ⟨ā⟩ | ɒ ⟨å⟩ | ɒː ⟨ā̊⟩ | |||

| Nasal | ã ⟨ą⟩ | ãː ⟨ą̇⟩ | |||||

Grammar

[edit]Nouns

[edit]| Case | "normal" endings | a-stems: (masc. neut.) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

| Nominative | -s | -ā | -ō (-as), -ā | -ō (yasn-ō) | -a (vīr-a) | -a (-yasna) |

| Vocative | – | -a (ahur-a) | -a (yasn-a), -ånghō | |||

| Accusative | -əm | -ō (-as, -ns), -ā | -əm (ahur-əm) | -ą (haom-ą) | ||

| Instrumental | -ā | -byā | -bīš | -a (ahur-a) | -aēibya (vīr-aēibya) | -āiš (yasn-āiš) |

| Dative | -ē | -byō (-byas) | -āi (ahur-āi) | -aēibyō (yasn-aēibyō) | ||

| Ablative | -at | -byō | -āt (yasn-āt) | |||

| Genitive | -ō (-as) | -å | -ąm | -ahe (ahur-ahe) | -ayå (vīr-ayå) | -anąm (yasn-anąm) |

| Locative | -i | -ō, -yō | -su, -hu, -šva | -e (yesn-e) | -ayō (zast-ayō) | -aēšu (vīr-aēšu), -aēšva |

Verbs

[edit]| Person | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | -mi | -vahi | -mahi |

| 2nd | -hi | -tha | -tha |

| 3rd | -ti | -tō, -thō | -ṇti |

Sample text

[edit]| Latin alphabet |

Avestan alphabet |

English Translation[66] |

|---|---|---|

|

ahyā. yāsā. nəmaŋhā. ustānazastō. rafəδrahyā.manyə̄uš. mazdā. pourwīm. spəṇtahyā. aṣ̌ā. vīspə̄ṇg. š́yaoθanā.vaŋhə̄uš. xratūm. manaŋhō. yā. xṣ̌nəwīṣ̌ā. gə̄ušcā. urwānəm.:: |

|

With outspread hands in petition for that help, O Mazda, I will pray for the works of the holy spirit, O thou the Right, whereby I may please the will of Good Thought and the Ox-Soul. |

Example phrases

[edit]The following phrases were phonetically transcribed from Avestan:[67]

| Avestan | English | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| tapaiti | It's hot | Can also mean "he is hot" or "she is hot" (in temperature) |

| šyawaθa | You move | |

| vō vatāmi | I understand you | |

| mā vātayaθa | You teach me | Literally: "You let me understand" |

| dim nayehi | Thou leadest him/her | |

| dim vō nāyayeiti | He/she lets you lead him/her | Present tense |

| mā barahi | Thou carryest me | |

| nō baraiti | He/she carries us | |

| θβā dim bārayāmahi | We let him/her carry thee | Present tense |

| drawāmahi | We run | |

| dīš drāwayāmahi | We let them run | Present tense |

| θβā hacāmi | I follow thee | |

| dīš hācayeinti | They accompany them | Literally: "They let them follow" |

| ramaiti | He rests | |

| θβā rāmayemi | I calm thee | Literally: "I let thee rest" |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Scholarship dicusses a wide range of possibilities regarding the dating of Avestan. A discussion on this topic is provided below.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Wells, John C. (1990), Longman pronunciation dictionary, Harlow, England: Longman, p. 53, ISBN 0-582-05383-8 entry "Avestan"

- ^ de Vaan & Martínez García 2014, p. 1: "Avestan is the language preserved in the sacred books of the Parsis, the ensemble of which is called the Avesta".

- ^ Cantera 2012, "The Avestan texts were probably composed [...] between the second half of the 2nd millennium bce and the end of the Achaemenid dynasty".

- ^ Schwartz 1985, p. 640: "For the traditional outlook of ancient Eastern Iran, the birthplace of Iranian culture, we must be guided by such realia as may be extracted from the religious texts which comprise the Avesta [...]".

- ^ Witzel 2000, p.48 :"The Vīdẽvdåδ list obviously was composed or redacted by someone who regarded Afghanistan and the lands surrounding it as the home of all Aryans (airiia), that is of all (eastern) Iranians".

- ^ Kellens 1987.

- ^ a b de Vaan & Martínez García 2014, p. 3: "Avestan, of which two varieties are known: Old Avestan (OAv.), also called Gathic Avestan or Avestan of the Gathas [Gāθās], and Young Avestan (YAv.)".

- ^ a b Daniel 2012, p. 47: "All in all, it seems likely that Zoroaster and the Avestan people flourished in eastern Iran at a much earlier date (anywhere from 1500 to 900 B.C.)".

- ^ a b c Skjaervø 2009, p. 43: "Young Avestan must have been quite close to Old Persian, which suggests it was spoken in the first half of the first millennium BC".

- ^ Hoffmann & Forssman 1996, pp. 31-32.

- ^ a b Skjaervø 2009, p. 43: "Old Avestan [...] is closely similar in grammar and vocabulary to the oldest Indic language as seen in the oldest part of the Rgveda and should therefore probably be dated to about the same time.".

- ^ Bailey 1987, "ARYA, an ethnic epithet in the Achaemenid inscriptions and in the Zoroastrian Avestan tradition".

- ^ Gnoli 1987, p. 20.

- ^ Gnoli 2002.

- ^ Kellens 1987, p. 35–44.

- ^ Schmitt 2000, p. 21.

- ^ a b Hoffmann 1989a, "Avestan is attested in two forms, known respectively as Old Avestan (OAv.) or Gathic Avestan and Young Avestan (YAv.)".

- ^ Cantera & Redard 2023, p. 3: "Avestan has three language states: Old Avestan, Middle Avestan and Young Avestan".

- ^ Kellens 1989, p. 36.

- ^ Schmitt 2000, p. 25: "Die Sprachform der avestischen Texte insgesamt ist nicht einheitlich; es lassen sich zwei Hauptgruppen unterscheiden, die nicht nur chronologisch, sondern in einzelnen Punkten auch dialektologisch voneinander zu trennen sind[.]".

- ^ a b c d Hoffmann 1989a.

- ^ "Encyclopaedia Iranica, AFGHANISTAN vi. Paṣ̌tō".

But it seems that the Old Iranic ancestor dialect of Paṣ̌tō must have been close to that of the Gathas.

- ^ Sims-Williams 1996, pp. 649-652.

- ^ Schmitt 1989, pp. 27-28.

- ^ Skjaervø 2009, pp. 50-51.

- ^ Hale 2004, p. 742.

- ^ Shahbazi, Alireza Shapur (1977). "The 'Traditional Date of Zoroaster' Explained". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 40: 25–35. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00040386.

- ^ Hintze 2015, p. 38: "Linguistic, literary and conceptual characteristics suggest that the Old(er) Avesta pre‐dates the Young(er) Avesta by several centuries".

- ^ Daniel 2012, p. 47: "Recent research, however, has cast considerable doubt on this dating and geographical setting".

- ^ Stausberg, Michael (2002). Die Religion Zarathushtras: Geschichte - Gegenwart - Rituale. Vol. 1 (1st ed.). W. Kohlhammer GmbH. p. 27. ISBN 978-3170171183.

Die 'Spätdatierung' wird auch in der jüngeren Forschung gelegentlich vertreten. Die Mehrzahl der Forscher neigt heutzutage allerding der 'Frühdatierung' zu

- ^ Bryant, Edwin (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture. Oxford University Press. p. 130.

Previously, a sixth century B.C.E. date based on Greek sources was accepted by many scholars, but this has now been completely discarded by present-day specialists in the field.

- ^ Daniel 2012, p. 47: "The similarity of the language and metrical system of the Gathas to those of the Vedas, the simplicity of the society depicted throughout the Avesta, and the lack of awareness of great cities, historical rulers, or empires all suggest a different time frame".

- ^ Bryant, Edwin (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture. Oxford University Press. p. 130.

The oldest parts of the Avesta, which is the body of texts preserving the ancient canon of the Iranian Zarthustrian tradition, is linguistically and culturally very close to the material preserved in the Rgveda.

- ^ Foltz, Richard C. (2013). Religions of Iran: From Prehistory to the Present. Oneworld Publications. p. 57. ISBN 978-1780743080.

The archaic nature of the Avestan language and its similarities to that of the Rig Veda, as well as the social and ecological environment it describes, would suggest a date somewhere between these two extremes, but not much later than 1000 BC.

- ^ Witzel 2000, p. 10: "Since the evidence of Young Avestan place names so clearly points to a more eastern location, the Avesta is again understood, nowadays, as an East Iranian text".

- ^ Gnoli, Gherardo (2011). "AVESTAN GEOGRAPHY". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III. Iranica Foundation. pp. 44–47.

"It seems likely that this geographical part of the Avesta was intended to show the extent of the territory that had been acquired in a period that can not be well defined but that must at any rate have been between Zoroaster's reforms and the beginning of the Achaemenian empire. The likely dating is therefore between the ninth and seventh centuries B.C.

- ^ Boyce, Mary (1996). A History Of Zoroastrianism: The Early Period. Brill. p. 191.

Had it been otherwise, and had Zoroastrianism been carried in its infancy to the Medes and Persians, these imperial people must inevitable have found mention in its religious works.

- ^ Skjaervø, P. Oktor (1995). "The Avesta as source for the early history of the Iranians". In Erdosy, George (ed.). The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia. De Gruyter. p. 166. ISBN 9783110144475.

The fact that the oldest Young Avestan texts apparently contain no reference to western Iran, including Media, would seem to indicate that they were composed in eastern Iran before the Median domination reached the area.

- ^ Grenet, Frantz (2005). "An Archaeologist's Approach to Avestan Geography". In Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Stewart, Sarah (eds.). Birth of the Persian Empire Volume I. I.B.Tauris. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-7556-2459-1.

It is difficult to imagine that the text was composed anywhere other than in South Afghanistan and later than the middle of the 6th century BC.

- ^ Vogelsang, Willem (2000). "The sixteen lands of Videvdat - Airyanem Vaejah and the homeland of the Iranians". Persica. 16: 62. doi:10.2143/PERS.16.0.511.

All of the above observations would indicate a date for the composition of the Videvdat list which would antedate, for a considerable time, the arrival in Eastern Iran of the Persian Acheamenids (ca. 550 B.C.)

- ^ Malandra, William W. (2009). "Zoroaster ii. general survey". Encyclopædia Iranica. Iranica Foundation.

Controversy over Zaraθuštra's date has been an embarrassment of long standing to Zoroastrian studies. If anything approaching a consensus exists, it is that he lived ca. 1000 BC give or take a century or so[.]

- ^ Kellens, Jean (2011). "AVESTA i. Survey of the history and contents of the book". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III. Iranica Foundation.

In the last ten years a general consensus has gradually emerged in favor of placing the Gāthās around 1000 BC [...]

- ^ Schmitt 2000, p. 21: "Die ältesten Texte dieses Corpus, die sog. Gathas stammen von Zarathustra selbst, dessen Lebensdaten von der Mehrheit der Forscher heute um das Jahr 1000 v. Chr. angesetzt [...] werden".

- ^ Hale 2004, p. 742: "Current scholarly consensus places his life considerably earlier than the traditional Zoroastrian sources are thought to, favoring a birth date before 1000 BC.".

- ^ Skjaervø 2009, p. 46: "Mid-second millennium:Composition of the ritual texts[...]the last direct evidence of which are the extant Old Avestan texts.".

- ^ Grenet, Frantz (2015). "Zarathustra's Time and Homeland - Geographical Perspectives". In Stausberg, Michael; Vevaina, Yuhan S.-D.; Tessmann, Anna (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. p. 22. ISBN 9781118785539.

All things considered, our chronological and cultural parameters tend to suggest locating Zarathustra (or, at least, the "Gathic community") [...] around c. 1500–1200 BC.

- ^ Kreyenbroek 2022, p. 202: "Still, the language of these Old Iranian texts stopped well short of evolving to a "Middle Iranian" stage".

- ^ Schmitt 2000, p. 21: "[Avestisch] läßt sich räumlich nicht exakt einordnen, da keine aus jüngerer Zeit bezeugten Sprachen es direkt fortsetzt.

- ^ Witzel, Michael. "THE HOME OF THE ARYANS" (PDF). Harvard University. p. 10. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

Since the evidence of Young Avestan place names so clearly points to a more eastern location, the Avesta is again understood, nowadays, as an East Iranian text, whose area of composition comprised – at least – Sīstån/Arachosia, Herat, Merw and Bactria.

- ^ Gnoli, Gherardo (1989), "Avestan geography", Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. 3, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 44–47,

It is impossible to attribute a precise geographical location to the language of the Avesta... With the exception of an important study by P. Tedesco (1921 [...]), who advances the theory of an 'Avestan homeland' in northwestern Iran, Iranian scholars of the twentieth century have looked increasingly to eastern Iran for the origins of the Avestan language and today there is general agreement that the area in question was in eastern Iran—a fact that emerges clearly from every passage in the Avesta that sheds any light on its historical and geographical background

. - ^ Mallory, J. P. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture. page 653. London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5. entry "Yazd culture".

- ^ Kuzmina 2007, p. 430.

- ^ Skjaervø 2011, p. 59: "Originally, this orally transmitted corpus must have been continuously updated linguistically as the spoke language evolved. Twice during this transmission, however, it was decided by priests that the text was no longer to be changed, but was to be preserved in the linguistic form it had at that time".

- ^ Hoffmann 1989a, "Every Avestan text, whether composed originally in Old Avestan or in Young Avestan, went through several stages of transmission before it was recorded in the extant manuscripts. During the course of transmission many changes took place".

- ^ Kellens 1998.

- ^ a b Skjaervø 2009, p. 46.

- ^ Hoffmann & Forssman 1996, p. 34.

- ^ Hintze 2014, "Like other parts of the Avesta, including Young Avestan sections of the Yasna, Visperad, Vidēvdād, and Khorde Avesta, the Yašts were produced throughout the Old Iranian period in the oral culture of priestly composition, which was alive and productive as long as the priests were able to master the Avestan language.".

- ^ Skjaervø 2011, p. 59: "The Old Avestan texts were crystallized, perhaps, some time in the late second millennium BCE, while the Young Avestan texts, including the already crystallized Old Avesta, were themselves, perhaps, crystallized under the Acheamenids, when Zoroastrianism became the religion of the kings".

- ^ Hoffmann 1989b, p. 90: "Mazdayasnische Priester, die die Avesta-Texte rezitieren konnten, müssen aber in die Persis gelangt sein. Denn es ist kein Avesta-Text außerhalb der südwestiranischen, d.h. persischen Überlieferung bekannt[...]. Wenn die Überführung der Avesta-Texte, wie wir annehmen, früh genug vonstatten ging, dann müssen diese Texte in zunehmendem Maße von nicht mehr muttersprachlich avestisch sprechenden Priestern tradiert worden sein".

- ^ Schmitt 2000, p. 26: "Andere Texte sind von sehr viel geringerem Rang und zeigen eine sehr uneinheitliche und oft grammatisch fehlerhafte Sprache, die deutlich verrät, daß die Textverfasser oder -kompilatoren sie gar nicht mehr verstanden haben".

- ^ Schmitt 2000, p. 22.

- ^ Boyce 1984, p. 3.

- ^ Hale 2004.

- ^ "AVESTA: YASNA: Sacred Liturgy and Gathas/Hymns of Zarathushtra". avesta.org.

- ^ Lubotsky, Alexander (2010). Van Sanskriet tot Spijkerschrift: Breinbrekers uit alle talen [From Sanskrit to Cuneiform: Brain teasers from all languages] (in Dutch). Amsterdam University Press. pp. 18, 69–71. ISBN 978-9089641793. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

General sources

[edit]- Bailey, Harold W. (1987). "Arya". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. 2. Iranica Foundation.

- Beekes, Robert S. P. (1988). A Grammar of Gatha-Avestan. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-08332-4.

- Boyce, Mary (1984). Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism. Textual Sources for the Study of Religion. Manchester UP.

- Cantera, Alberto; Redard, Céline (2023). An Introduction to Young Avestan: A Manual for Teaching and Learning. Translated by Niroumand, Richard. Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447120920.

- Cantera, Alberto (2012). "Preface". In Cantera, Alberto (ed.). The transmission of the Avesta. Iranica. Vol. 20. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-06554-2.

- Daniel, Elton L. (2012). The History of Iran. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0313375095.

- Gnoli, Gherardo (1987). The Idea of Iran - An Essay on its Origin. Serie orientale Roma. Vol. 62. Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. ISBN 9788863230697.

- Gnoli, Gherardo (2002). "The "Aryan" language" (PDF). Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam. 26: 84–90. ISSN 0334-4118.

- Hale, Mark (2004). "Avestan". In Roger D. Woodard (ed.). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56256-2.

- Hintze, Almut (2015). "Zarathustra's Time and Homeland - Linguistic Perspectives". In Stausberg, Michael; Vevaina, Yuhan S.-D.; Tessmann, Anna (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 9781118785539.

- Hintze, Almut (2014). "Yašts". Encyclopædia Iranica. Iranica Foundation.

- Hoffmann, Karl (1989a). "Avestan language". Encyclopedia Iranica. Vol. 3. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 47–52.

- Hoffmann, Karl (1989b). Der Sasanidische Archetypus - Untersuchungen zu Schreibung und Lautgestalt des Avestischen (in German). Reichert Verlag. ISBN 9783882264708.

- Hoffmann, Karl; Forssman, Bernhard (1996), Avestische Laut- und Flexionslehre, Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft 84, Institut fur Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck, ISBN 9783851246520

- Kellens, Jean (1987). "Avesta". Encyclopædia Iranica. vol. 3. New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul. pp. 35–44.

- Kellens, Jean (1998). "Considérations sur l'histoire de l'Avesta". Journal Asiatique. 286 (2): 451–519. doi:10.2143/JA.286.2.556497.

- Kellens, Jean (1989). "Avestique". In Schmitt, Rüdiger (ed.). Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum. Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag.

- Kellens, Jean (1990), "Avestan syntax", Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. 3/sup, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul

- Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (August 2022). "Early Zoroastrianism and Orality". Oral Tradition among Religious Communities in the Iranian-Speaking World. Cambridge: Harvard University.

- Kuzmina, Elena E. (2007). J.P. Mallory (ed.). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. Brill. ISBN 978-90-474-2071-2.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (1989). "Die altiranischen Sprachen im Überblick". In Schmitt, Rüdiger (ed.). Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum (in German). Reichert Verlag. ISBN 9783882264135.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2000). Die iranischen Sprachen in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag.

- Schwartz, Martin (1985). "The Old Eastern Iranian World View According to the Avesta". In Gershevitch, I. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2: The Median and Achaemenian Periods. Cambridge University Press. pp. 640–663. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521200912.014. ISBN 9781139054935.

- Skjaervø, P. Oktor (2011). "Avestan Society". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199390427.

- Skjaervø, P. Oktor (2009). "Old Iranian". In Windfuhr, Gernot (ed.). The Iranian Languages. Routledge. ISBN 9780203641736.

- Skjærvø, Prod Oktor (2006), Old Avestan, fas.harvard.edu

- Skjærvø, Prod Oktor (2006), Introduction to Young Avestan, fas.harvard.edu

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas (1996). "EASTERN IRANIAN LANGUAGES". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. VII. Iranica Foundation.

- de Vaan, Michiel; Martínez García, Javier (2014). Introduction to Avestan (PDF). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-25777-1.

- Witzel, Michael (2000). "The Home of the Aryans". In Hinze, A.; Tichy, E. (eds.). Festschrift für Johanna Narten zum 70. Geburtstag (PDF). J. H. Roell. doi:10.11588/xarep.00000114.

Further reading

[edit]- UESUGI, Heindio; CATT, Adam Alvah, eds. (2024). Old Avestan Dictionary. Asian and African Lexicon. Vol. 67. Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa; Tokyo Language of Foreign Studies. ISBN 9784863375420.

External links

[edit]- Information on Avestan language at avesta.org

- Old Iranian Online (including Old and Young Avestan) by Scott L. Harvey and Jonathan Slocum, free online lessons at the Linguistics Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- Old Avestan and Young Avestan at Harvard University

- Corpus Avesticum Berolinense An Online Edition of the Zoroastrian Rituals in the Avestan Language

- Text samples and Avesta Corpus at TITUS.

- Hoffmann, Karl. "Avestan language". Encyclopedia Iranica.

- Boyce, Mary. "Avestan people". Encyclopedia Iranica.

- glottothèque – Ancient Indo-European Grammars online, an online collection of introductory videos to ancient Indo-European languages produced by the University of Göttingen

KSF

KSF