Balsam Lake Mountain Fire Observation Station

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 17 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 17 min

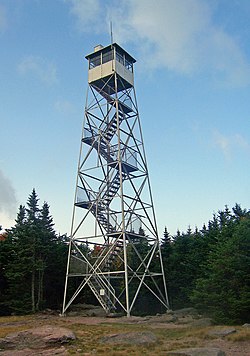

Balsam Lake Mountain Fire Observation Station | |

Tower in 2008 | |

| Location | Summit of Balsam Lake Mountain, Hardenburgh, New York |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Kingston, New York |

| Coordinates | 42°4′11″N 74°34′28″W / 42.06972°N 74.57444°W |

| Area | 10.9 acres (4.4 ha) |

| Built | 1930[2] |

| Architect | Aermotor Corporation |

| MPS | Fire Observation Stations of New York State Forest Preserve MPS |

| NRHP reference No. | 01001038[1] |

| Added to NRHP | September 23, 2001 |

The Balsam Lake Mountain Fire Observation Station is located at the summit of the mountain of that name in the Town of Hardenburgh, New York, United States. It comprises a steel frame fire lookout tower, the observer's cabin and privy and the jeep road to the complex.

Balsam Lake Mountain, the westernmost of the Catskill High Peaks, was the site of the first fire lookout tower in New York in 1887, when a nearby sportsmen's club built it to protect their lands below the mountain.[2][3] It was later taken over by the state, which built several towers culminating in the current one. The tower was staffed until 1988.

After being closed for much of the 1990s, the tower was proposed for demolition as one of five remaining on state-owned Forest Preserve land in the Catskill Park. Hikers and local residents rallied to save it, and after the state's Department of Environmental Conservation changed its mind, it was restored and reopened. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2001,[1] the highest-elevation property in Ulster County to be listed.[note 1]

Property

[edit]The nominated property includes a 500-foot (152 m) square area around the tower and the entire 3-mile (4.8 km) jeep road to the summit from Mill Brook Road between Balsam Lake Mountain and Dry Brook Ridge, now marked as a hiking trail. This gives it a total of 10.9 acres (4.4 ha) of land, most of it owned by the state but some of it property of the descendants of Jay Gould, whose Furlow Lodge estate is in the area.[4][5] The tower and road are considered contributing resources; three other buildings near the tower are related to it in function but are non-contributing.[2]

The tower and other buildings are around a small clearing at the mountain's 3,723-foot (1,135 m) summit. On all sides are boreal forest consisting of thick balsam fir and red spruce. This is the westernmost large stand of this kind of forest in the Catskills as no peaks west of Balsam Lake rise above 3,500 feet (1,067 m), the elevations where it is most commonly found.[2]

The old road arrives from the east; a foot trail leaves the clearing to the south. Along much of its length the road is accompanied by old telephone poles and downed wire from the communication system that once served the tower. It follows red plastic markers down a winding course past a metal DEC gate at the boundary between public and private land to the northeast shoulder of the mountain at 3,300 feet (1,006 m). There it joins and follows another old road, now with the blue markers of the Dry Brook Ridge Trail, down to where it crosses paved Mill Brook Road.[2]

The tower itself is 47+1⁄2 feet (14.5 m) tall. It is a steel frame structure, anchored by bolts on surface plates into the exposed sedimentary bedrock at the summit, gradually sloping up to the enclosed cab at the top. Seven flights of steel stairs provide access from the ground.[2]

Next to the tower, at the corner of the road and the summit clearing east of it, is the observer's cabin. It is a one-story batten-sided gable-roofed hut on a concrete foundation with a metal roof. Just inside the woods to the north is the wooden privy. In the summit clearing there is also a more contemporary wooden picnic table[6] and, at the south end, the remains of an older foundation.[2]

History

[edit]The tower was built, privately at first, to answer a public need. Later it became public property, even as that need declined. Since then it has found a new purpose.

1885–1909: Establishment by Balsam Lake Club

[edit]The forests of the Catskills generally (though not those around Balsam Lake and its neighboring peaks[7]) had been heavily exploited over the course of the 19th century by various forest-product industries, particularly tanning, which depended on the bark of the eastern hemlock for tannin, and left many stands of peeled first-growth trees to rot and die when they had taken all the usable bark. Loggers harvested commercial-grade timber for furniture and made charcoal in open pits in the woods.[8]

Many simply abandoned the lands they owned after they had made their money, leaving them to default to the counties in question, which then owed the unpaid property taxes to the state. The distressed forests also heightened the risk of forest fires and their attendant damage to local communities. In 1885 the Ulster County delegation to the state Assembly resolved both issues by getting the Catskills included with the Adirondacks in the new Forest Preserve. The county's forest lands were transferred to the state to be kept forever wild, and with state ownership came state supervision of fire protection efforts. Nine years later, that legislation would be incorporated into a new version of the state constitution as Article 14, with language closing all the loopholes business-friendly state regulators at the Forest Commission had been trying to use in the meantime.[8][9]

In 1887, two years after the Forest Preserve was created, members of the Balsam Lake club who hunted and fished on its lands near the headwaters of the Beaver Kill south of the mountain, decided to build a tower on the summit to detect fires early. A crew of workmen supervised by the club's warden built a small tower from trees cut near the summit.[3]

That tower stood until 1901, when members of the club went to the summit and found it destroyed by a fire, the probable result of a lightning strike. A new tower, 35 feet (11 m) in height, was built to replace it in 1905. The members of the Balsam Lake club continued to maintain and staff it until 1909, when the state's Forest, Fish and Game Commission (FFGC), a predecessor agency to today's Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), took over the tower.[2][3]

1909–1970: Public use

[edit]Following destructive fires during severe droughts earlier in the decade, FFGC supervisor Hames Whipple had turned to towers as a means of fire detection, since the previous methods of ground patrols[10] had not been successful. He had done so after consulting with E.E. Ring, manager of Maine's state forestry agency, who had put up nine at locations around that state.[11] "In my opinion," Ring wrote him, "one man located at a station will do far more effectual work in discovering and locating fires than a hundred men already patrolling."[12]

The Balsam Lake tower joined those already operated by the state in the Catskills on Belleayre and Hunter mountains. Because of its height compared to the peaks to its west in Delaware County, it offered an excellent vantage point from which to spot fires in that area as well as its immediate surroundings in Ulster County. Views were unobstructed for 12–18 miles (19–29 km) in all directions.[2]

After taking over, the FFGC spent $38 ($1,300 in modern dollars[13]) repairing the tower. The state also added a dedicated telephone line along a truck road it built connecting to Mill Brook Road at the north so the observers stationed at the tower would not have to hike to the tower from the club's very remote location at the end of a long road up an isolated river valley. In its first year, according to the commission's annual report, observers spotted fires as far away as Fallsburg and Liberty in Sullivan County and in the Shawangunks, far to the south and southeast.[2]

In 1918, the state replaced the crude shelter for observers, described by one as a "shanty", with a more permanent cabin. The next year the open wooden tower the club had built was replaced with a 47+1⁄2-foot (14.5 m) Aermotor steel tower.[3] Whether this is the current tower is not clear. The Historic Lookout Register says it was in turn replaced with the current tower in 1930, but records from the Conservation Commission, which the FFGC had become by then, show no expenditure for a new tower.[2] DEC's webpage for the Wild Forest, however, gives 1930 as the construction date for the current tower.[14]

Mike Todd, the observer from the time the cabin was constructed until 1947, was sometimes able to spot fires as far away as Northeastern Pennsylvania, many miles to the southwest. During his tenure he claimed to have shot over 900 porcupines chewing on the cabin to prevent damage.[15] He also took black bears around the tower and on his drive up.[16]

In the early 1960s the state replaced the 1918 cabin with the current one. Unlike older observer's cabins in the Forest Preserve, the one on Balsam Lake lacks a porch. This was the most significant change to any aspect of the fire tower complex after the construction of the current tower.[2] During that time the observers were busy. A drought in 1962 led to many fires, and similar conditions the following year resulted in Governor Nelson Rockefeller ordering the closing of the Forest Preserve in 1963 and again for short periods the following year.[17]

Another observer, Larry Baker, ended a search and rescue operation in 1968. He found some missing Boy Scouts from Long Island who had gotten separated from their group, a short distance from the tower at the lean-to near the south end of the summit.[16] That coincided with the beginning of the end of the era in which the fire towers were an essential component of the region's fire control system. Since the 1950s, better public education about the causes of forest fires, along with improved local fire departments, had led to a decline in fires. Aerial observers, who could cover the whole region several times a day, were becoming a more cost-effective way to detect fires, and the state slowly began closing the towers down and dismantling them.[18]

1971–present: Decline and restoration

[edit]From 1971 onwards, Catskill forest historian Michael Kudish describes the Balsam Lake tower as being staffed "primarily for the entertainment of hikers".[19] One of those was CBS News anchorman Dan Rather, who owns property in Hardenburgh[20] and, observer Tim Hinkley recalls, came up with his daughter one day in 1988. Later that year Hinkley became the Balsam Lake Mountain fire tower's last observer as it was closed.[16] Three years later, with the closure of the Red Hill fire tower in the southern Catskills after a brief reopening due to severe drought, the fire tower era ended.[18]

The tower remained, its lower flight removed in 1993 to prevent public access.[6] Hikers continued to climb it for the views from the steps, but it was no longer maintained and subject to deterioration. In 1990 George Profous, a DEC forester, wrote in a draft planning document that the Red Hill tower, one of the five left in the Catskill Park along with Balsam Lake, should be dismantled as no longer in conformance with state management guidelines for Forest Preserve lands. He hoped that public opposition would emerge and save the remaining towers, which it did.[15]

The Catskill Center for Conservation and Development and DEC helped the communities near the fire towers form the Catskill Fire Tower Restoration Project. Volunteers in the area raised $16,000 through benefit concerts and art exhibits. DEC employees and AmeriCorps volunteers began restoring the tower in 1999, putting in new stairs and a new roof and windows for the cab. After new ironwork was installed, the tower reopened in 2000.[21]

The tower today

[edit]Its views have been described as the finest from any Catskill fire tower,[22] and it is a common destination for hikers. Aspiring members of the Catskill Mountain 3500 Club come because the peak is required for membership,[23] other hikers come to complete the Adirondack/Catskill Fire Tower Challenge,[24] and some come just for the view from the tower itself.

It can be approached from three directions. The two most common use the Dry Brook Ridge Trail, blazed with blue plastic markers, to connect to the red-blazed Balsam Lake Mountain Trail, which makes a short loop across the summit. South of the fire tower it connects to the yellow-blazed Mill Brook Ridge Trail, which offers a longer approach from the west over that mountain.[5]

The northern approach, the most popular,[14] follows the old jeep road in its entirety from Mill Brook Road,[25] the highest trailhead in the Catskills at 2,580 feet (790 m).[note 2] It is longer but less of a climb[14] than the southern approach from the slightly lower trailhead at the end of Beaverkill Road.[26] In 1998 the Mill Brook Ridge Trail was built. It starts from the west end of Alder Lake near Turnwood and runs 6.7 miles (10.8 km) to a junction with the Balsam Lake Mountain Trail 0.1 miles (0.16 km) south of the fire tower. It is considered the most ambitious route[14] but is the least used.[27]

Graham and Doubletop mountains, Balsam Lake's higher neighbors to the east, dominate the view from the fire tower, with Slide, the highest Catskill peak, between them in clear weather.[22] In the best of conditions the Blackhead Range at the northeast corner of the Catskills is visible as well.[27] To the north Dry Brook Ridge appears as a single peak rather than a long ridge, with Bearpen, highest peak in New York outside the Forest Preserve, visible in clear weather.[25] Westward Woodpecker Ridge and the eastern summit of Mill Brook Ridge are closest, and in the distance the view looks down on the lower peaks in eastern Delaware County, with Mount Pisgah, home to Ski Bobcat, standing out above most of them. South the view takes in the Beaver Kill Range, with Peekamoose, Table and Red Hill and its fire tower also visible.[22] In clear weather the Shawangunk Ridge is also visible to the southeast, and Elk Mountain, highest peak in Northeastern Pennsylvania, is on the southwest horizon.[27]

As part of the restoration project, interpretive guides man the tower on weekends during the warmer months.[23] Camping is forbidden on the summit except in winter.[28] Those who wish to stay the night on the mountain can camp in a lean-to on the south slope below the spring at about 3,300 feet (1,000 m).

See also

[edit]- Catskill Mountain fire towers

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Ulster County, New York

Notes

[edit]- ^ The next two highest are the Red Hill and Mount Tremper fire towers, at 2,990 feet (910 m) and 2,740 feet (840 m) respectively.

- ^ The Quaker Clearing trailhead where the south approach begins is the next highest, at 2,500 feet (760 m), with the Slide Mountain trailhead on Ulster County Route 47 third at 2,400 feet (730 m).

References

[edit]- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Wes Haynes (May 2000). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Balsam Lake Mountain Fire Observation Station". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2010-02-20. See also: "Accompanying two photos". Archived from the original on 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- ^ a b c d Podskosch, Martin (2000). Fire Towers of the Catskills: Their History and Lore. Fleischmanns, New York: Purple Mountain Press. p. 35. ISBN 1-930098-10-3.

- ^ Renehan Jr., Ed (April 2005). "Jay Gould's Roxbury". Guide. Catskill Mountain Foundation. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

Another local Gould is Jay's great-grandson Kingdon Gould, Jr., the grandson of George Gould. A Yale-educated attorney and longtime developer of real-estate in the Washington, D.C. area, Kingdon spends his summers at George Gould's Furlow Lodge in nearby Arkville, where he is surrounded by several other Gould homes ...

- ^ a b Central Catskill Trails (Map) (8th ed.). 1:63,360. Cartography by Koch, Ted and Benjamin, Sheryl. New York – New Jersey Trail Conference. 2005. § 6G. ISBN 1-880775-46-8.

- ^ a b Wadsworth, Bruce; Adirondack Mountain Club Schenectady chapter (1988). Guide to Catskill Trails (2nd, with revisions ed.). Lake George, NY: Adirondack Mountain Club. pp. 241–43. ISBN 0-935272-71-2.

- ^ Kudish, Michael (2000). The Catskill Forest: A History. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press. p. 91. ISBN 1-930098-02-2.

The terrain along the Mill Brook Ridge Range is among the least disturbed by people in the Catskills ...

- ^ a b Evers, Alf (1972). The Catskills: From Wilderness to Woodstock. Woodstock: The Overlook Press. pp. 585–89. ISBN 0-87951-162-1.

- ^ "New York State Constitution Article XIV". State of New York, reprinted at adirondack-park.net. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- ^ Podskosch, 14.

- ^ Podskosch, 12.

- ^ Forest, Fish and Game Commission of the State of New York Report 1908, Albany: J.B. Lyon, State Printers, 1909, 45-46, cited at Podskosch, 12.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Balsam Lake Mountain Wild Forest". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 2010. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ a b Herring, Hubert (November 5, 2000). "Phoenicia Journal; Great Views, and a Peek Into the Past". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ^ a b c Podskosch, 36.

- ^ Podskosch, 23.

- ^ a b Podskosch, 24.

- ^ Kudish, 95.

- ^ Gref, Barbara (July 22, 2000). "Rocky Revolution: A little trouble in big paradise". Times-Herald Record. Ottaway Community Newspapers. Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

In this case, 1,000 acres is to be divvied up for lots up to 100 acres for exclusive homes. These will rival the homes of newsman Dan Rather, singer Shania Twain, financiers and CEOs who are already tucked into these woods.

- ^ "Balsam Lake Mountain Fire Tower". Catskill Center for Conservation and Development. Archived from the original on January 12, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ a b c McAllister, Lee; Ochman, Myron (1989). Hiking the Catskills. New York: New York-New Jersey Trail Conference. p. 252. ISBN 0-9603966-6-7.

- ^ a b "Balsam Lake Mountain; Balsam Lake Fire Tower". Catskill Mountain 3500 Club. 2007–2010. Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ "Fire Tower Challenge". Adirondack Mountain Club, Glens Falls-Saratoga chapter. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ a b Kick, Peter (2006). AMC's Best Day Hikes in the Catskills & Hudson Valley. Boston: Appalachian Mountain Club. pp. 240–43. ISBN 1-929173-84-9.

- ^ White, Carol and David (2002). Catskill Day Hikes for All Seasons. Lake George, NY: Adirondack Mountain Club. pp. 140–41. ISBN 0-935272-54-2.

- ^ a b c New York Walk Book (7th ed.). Mahwah, NJ: New York-New Jersey Trail Conference. 2001. p. 246. ISBN 1-880775-30-1.

- ^ "Part 190: Use of State Lands — Page 1: Section 190.3". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 2007–2010. Archived from the original on 15 March 2010. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

d. Except in an emergency, or during the period December 15 to April 30 each year in the Adirondack Park, or during the period December 21 to March 21 each year in the Catskill Park, no person may camp on lands under the jurisdiction of the department which are located at an elevation in excess of 4,000 feet above sea level in the Adirondack Park or in excess of 3,500 feet above sea level in the Catskill Park.

External links

[edit]- Balsam Lake Fire Tower at Catskill Center website

- Balsam Lake Mountain Fire Tower at the Fire Towers of New York Site

KSF

KSF