Barton government

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

Barton government | |

|---|---|

| |

| In office | |

| 1 January 1901 – 24 September 1903 | |

| Monarch | Victoria Edward VII |

| Prime Minister | Sir Edmund Barton |

| Party | Protectionist |

| Status | Caretaker (to 30 March 1901) Minority (from 30 March 1901) |

| Origin | Chosen by Lord Hopetoun |

| Demise | Barton's retirement |

| Predecessor | N/A |

| Successor | Deakin government (I) |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal

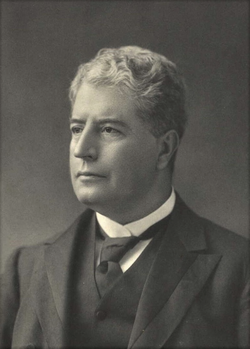

1st Prime Minister of Australia Electoral history |

||

The Barton government was the first federal executive government of the Commonwealth of Australia. It was led by Prime Minister Sir Edmund Barton, from 1 January 1901 until 24 September 1903, when Barton resigned to become one of the three founding judges of the High Court of Australia.[1]

Background

[edit]Federation

[edit]The background to the Barton government saw the six British colonies of Australia vote to federate as one Commonwealth. Sir Henry Parkes was among the leading voices calling for Federation and had kick-started the movement with his Tenterfield Oration of 1889:[2]

Australia [now has] a population of three and a half millions, and the American people numbered only between three and four millions when they formed the great commonwealth of the United States. The numbers were about the same, and surely what the Americans had done by war, the Australians could bring about in peace, without breaking the ties that held them to the mother country.

Known himself as the "Father of Federation", Parkes would die before the project was completed. Shortly before his death in 1896, Parkes called on Edmund Barton to take up the struggle of leading the push for Federation. Barton in turn announced:[3]

There is one great thing which above all activates me in my political life, and will activate me until it is accomplished, and that is the question of the union of the Australian colonies.

After a series of constitutional conventions and referendums, the colonies agreed to federate as a new "commonwealth": the Commonwealth of Australia. The Constitution of Australia, with its provision for the foundation of a bicameral Australian Parliament, was endorsed by the Imperial Parliament in Britain and signed into law by Queen Victoria. Lord Hopetoun, a Lord-in-waiting to Queen Victoria and a former Governor of the Colony of Victoria, was selected as Australia's first Governor-General, and the appointment of the first Cabinet was put in train.

First cabinet

[edit]

Edmund Barton became the newly Federated Australian nation's first prime minister at a grand ceremony in Centennial Park, Sydney, on 1 January 1901.[4] He and his cabinet were sworn in by Australia's first Governor-General, Lord Hopetoun before an estimated crowd of 250,000 people.[3] Hopetoun had first offered the position to the Premier of New South Wales Sir William Lyne (an opponent of Federation), but the other members of Cabinet and the general population saw Barton as the logical choice. The appointment was temporary, to organise the first general election.[3]

Barton was sworn in as prime minister and Minister for External Affairs and his Cabinet consisted of a number of ex-premiers: Sir George Turner of Victoria was Treasurer, Charles Kingston of South Australia was Minister for Trade and Customs, Sir John Forrest of Western Australia was Postmaster-General, Sir James Dickson of Queensland was Minister for Defence, and Sir William Lyne was Minister for Home Affairs. Other than Barton, Alfred Deakin was the only other member of the original Cabinet who had not served as a premier but, like Barton, he had been a strong advocate for Federation. Barton appointed two other honorary Cabinet positions: Richard O'Connor of New South Wales, to serve as Vice-President of the Executive Council, and Elliott Lewis, the Premier of Tasmania.[3]

A reshuffle was necessitated by the death of Dickson on 10 January, with James Drake joining Cabinet as Postmaster-General, and Forrest shifting to Defence. Following the first election, Philip Fysh of Tasmania replaced Elliott Lewis as Minister without Portfolio. Lewis had decided not to be a candidate for federal parliament, and he and Sir James Dickson remain the only people to have served in a federal government without ever having been members of the Australian Parliament.[3]

The vast new Federation had a population of just 3.8 million, was yet to elect a Parliament, and had not settled on a location for a capital city.[5]

Thus, in January 1901, in an election speech, Barton set out such priorities for the nation as: providing for female franchise; setting up a High Court of Australia; selecting a site for a federal capital; setting up a revenue system through tariffs; establishing a system to adjudicate interstate labour disputes; and building an east–west railway across the continent.[6]

First election: Protectionists v Free Traders

[edit]The major issue of the first general election of March 1901 was to be whether or not Australia would be established as a Protectionist or Free Trade nation. Prior to Federation, the Colony of Victoria had settled on Protectionism, while New South Wales had favoured Free Trade. In the absence of strong party affiliations outside the Australian Labor Party (which was divided on the question), candidates tended to be defined in relation to their attitude to trade, and while Barton sought compromise, the Free Trader George Reid pushed for the question to be a central election issue.[3]

Meanwhile, the candidates generally agreed on the need to establish a restrictive immigration system (recalled as the White Australia Policy) to preference British and European migrants. Other key issues included the need for the establishment of a transcontinental railway, a High Court, a system for arbitrating on industrial disputes, and the provision of an old age pension.[3]

Following the March election, Barton's Protectionists won 27 seats in the newly formed 75-member Australian House of Representatives. Reid's Free Trade supporters won 32 seats, leaving the Labor Party, on 16 seats, with the balance of power. Labor confirmed "support in return for concessions" and backed Barton, who became prime minister in a minority government. The 36 seat Senate meanwhile held just 14 Senators declaring themselves in support of the Barton government.[3]

First Parliament

[edit]

The first Parliament was opened on 9 May 1901. Shortly before her death in January 1901, Queen Victoria had designated her grandson, the Duke of Cornwall and York (later King George V) to preside over the opening of the first Parliament of Australia. The ceremony took place with much British pomp and circumstance in Melbourne's Royal Exhibition Building on 9 May 1901 and Parliament was to sit at Victoria's Parliament House, Melbourne for some 26 years, while a suitable site for a federal capital was established.

While much of its business was centred on establishing the machinery of government, among the most significant legislation passed by the first Parliament were immigration restrictions and tariff protections.

The Duke of York toured Australia and opened the first Parliament in 1901. After an expenses dispute, Parliament refused to augment the income received by the Governor-General with an additional annual allowance, and Lord Hopetoun resigned, sailing for Britain in July 1902.[7] South Australia's Governor, Lord Tennyson, became Australia's second Governor-General. The term of the first parliament was from May 1901 to October 1902. It enacted 59 acts, and, in accordance with the provisions of the new Constitution, established the legal, financial and administrative foundations of the Commonwealth.

Immigration

[edit]The new Parliament quickly moved to restrict immigration to maintain Australia's "British character", and the Pacific Island Labourers Bill and the Immigration Restriction Bill were passed shortly before parliament rose for its first Christmas recess. Nevertheless, the Colonial Secretary in Britain made it clear that a race based immigration policy would run "contrary to the general conceptions of equality which have ever been the guiding principle of British rule throughout the Empire", so the Barton government conceived of the "language dictation test", which would allow the government, at the discretion of the minister, to block unwanted migrants by forcing them to sit a test in "any European language". Race had already been established as a premise for exclusion among the colonial parliaments, so the main question for debate was who exactly the new Commonwealth ought to exclude, with the Labor Party rejecting Britain's calls to placate the populations of its non-white colonies and allow "aboriginal natives of Asia, Africa, or the islands thereof". There was opposition from Queensland and its sugar industry to the proposals of the Pacific Islanders Bill to exclude "Kanaka" labourers, however Barton argued that the practice was "veiled slavery" that could lead to a "negro problem" similar to that in the United States and the Bill was passed.[3]

The restrictive measures established by the first parliament gave way to multi-ethnic immigration policies only after the Second World War, with the "dictation test" itself being finally abolished in 1958 by the Menzies government.[8]

Tariffs

[edit]The occasion of the first federal Budget saw the Protectionist supporters of the Barton government clash with the Free Trade Opposition led by George Reid. The Customs Tariff Act took some five months to debate, until finally receiving Royal Assent in September 1902. In the end it was less protectionist than the standard set in the new State of Victoria. The new federation had to establish uniform customs duties and end the trade barriers which had existed between the colonies.[3]

Barton travelled to Britain for the Coronation of King Edward VII and the Colonial Conference of 1902 where he came up against the push for "free trade within the Empire".

Women's suffrage

[edit]In 1902, a historic law granting women's suffrage throughout the Commonwealth was enacted[5] entitled the Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902. Prior to Federation, women had already gained these rights in South Australia and Western Australia.

Foreign policy and defence

[edit]Prior to Federation, Britain's Australian colonies had dispatched forces to assist Britain in the Boer War in South Africa. Britain sought further forces from the new Commonwealth, and Barton secured the agreement of the new Parliament, though Australian Federal forces did not reach South Africa until the final stages of that war. Barton was an Imperial loyalist, and represented Australia at the 1902 Coronation of Edward VII. Whilst in Britain, he was honoured with the title Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Michael and St George (KGCMG). He also secured support for an expanded British naval squadron at Sydney which would assist with training a local force and lobbied for preferential treatment for Australian trade within the British Empire.[5]

Barton received congratulations from the Pope on the tolerance shown to Catholics within Australia, and Barton in return offered assurances that this would continue. The exchange prompted "strenuous disapproval" in the form of a petition from some thousands of Australian Protestants.[3]

Towards the end of his term in office, Britain and Japan concluded the Anglo–Japanese naval agreement, for which Barton managed to secure the approval of the Australian Parliament and the gratitude of Japan in the form of the Order of the Rising Sun First Class.[5]

Barton's resignation

[edit]

According to political historian Brian Carroll, Barton faced a serious crisis when Kingston resigned from his ministry in July 1902 over a dispute with Labor over the jurisdiction of the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill. Many were by this stage concerned as to Barton's fortitude for a political agenda beyond the establishment of a federation. Barton's health declined and in August 1903, he collapsed in his room at Parliament and resigned the following month to take up a position with the newly established High Court of Australia.

He was succeeded as prime minister by his friend, colleague and co-campaigner in the cause of Federation, Alfred Deakin, who also became Minister for External Affairs in a Cabinet which remained largely unchanged.[3]

High Court

[edit]One of the most important issues dealt with by the new parliament was the establishment of a High Court. The Judiciary Act 1903, enacted in August, established the High Court of Australia with three, rather than the five judges originally proposed. On 24 September 1903, Barton resigned as prime minister, to accept appointment to new Court, together with Cabinet colleague Richard O'Connor.[5] The gifted constitutional scholar Samuel Griffith became the first Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia and was instrumental in the shaping of Australia's legal system.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Barton, Sir Edmund (Toby) (1849–1920)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- ^ "ABC Rural". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 13 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Brian Carroll; From Barton to Fraser; Cassell Australia; 1978

- ^ "Barton Index". primeministers.naa.gov.au.

- ^ a b c d e "Barton in Office". primeministers.naa.gov.au.

- ^ "Barton Elections". primeministers.naa.gov.au.

- ^ "Hopetoun, seventh Earl of (1860–1908)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- ^ "Fact Sheets". Archived from the original on 1 September 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ Michael Meek; LBC Nutshell: The Australian Legal System; third Edition; 1999.

KSF

KSF