Battle of Columbus (1865)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 15 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 15 min

32°28′01″N 84°59′49″W / 32.467°N 84.997°W

| Battle of Columbus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Major General James H. Wilson |

Major General Howell Cobb General Robert Toombs | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Two cavalry divisions (9,000 cavalry) | 3,250 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 60 | 151 | ||||||

The Battle of Columbus, Georgia (April 16, 1865), was the last conflict in the Union campaign through Alabama and Georgia, known as Wilson's Raid, in the final full month of the American Civil War.

Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson had been ordered to destroy the city of Columbus as a major Confederate manufacturing center. He exploited enemy confusion when troops from both sides crowded on to the same bridge in the dark, and the garrison withheld its cannon fire. Next morning, Wilson laid waste to the city and took many prisoners.

Several authorities claim Columbus should be classified as the last battle of the Civil War, while others point to a battle which occurred after the Confederacy was vanquished, the Battle of Palmito Ranch. The Battle of Columbus is also known as the Battle of Girard, Alabama (now Phenix City).

Events leading to the battle

[edit]

After the Union victory in the Battle of Nashville (December 15–16, 1864), Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas ordered Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson to march into the heart of the Deep South and destroy the major Confederate supply centers at Selma, Alabama, and Columbus, Georgia.

Wilson left Gravelly Springs, Alabama, on March 22, 1865, heading for Selma, a major manufacturing and supply center. The Battle of Selma was fought on April 2, 1865, against the leadership of Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, whose men were hopelessly outnumbered by the Union troops. The battle took place on the same day the Confederate capital of Richmond fell to the Army of the Potomac. Forrest managed to inflict heavy casualties on the attackers, but Wilson's raiders finally broke through the defenses and captured Selma by 7 p.m. that evening. Wilson's men destroyed all the military supplies and looted the city before moving on.

On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House. Confederate General Joe Johnston's army was still intact, as were the armies in Alabama and Mississippi and in the Trans-Mississippi theater. Also, because of the lack of communications, General Wilson was not aware of Lee's surrender. He continued his raids.

On April 12, 1865, Wilson's men marched into the former Confederate capital of Montgomery, Alabama, encountering token resistance from the Confederates.

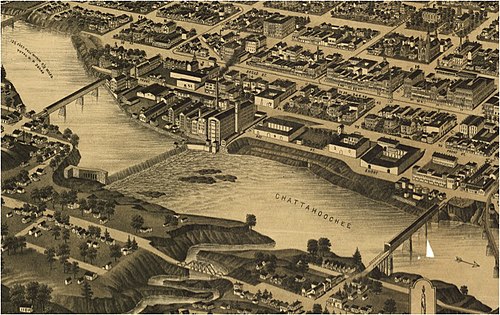

Wilson's next target was the manufacturing city of Columbus, Georgia, the largest-surviving supply city in the South. Columbus was second only to Richmond in providing the industrial support for the war, and Richmond had been taken. Columbus was located on the Chattahoochee River, where there was a major naval construction facility. A new ironclad, the CSS Muscogee, was docked at Columbus waiting to be completed.

Abraham Lincoln was fatally shot in Washington on Good Friday, April 14, and he died the next day, but Wilson had not yet learned of this.

Columbus alerted to the attack

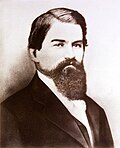

[edit]The Confederates in Columbus were well aware that Wilson's 13,000 men were on the way. Confederate Major General Howell Cobb had been placed in charge of whatever forces he could gather, and he did his best to prepare to defend Columbus.[1]

Cobb had about 3,500 men in his forces, most of them Georgia and Alabama home guard units and civilian volunteers. On April 16, 1865, Columbus newspapers warned citizens to leave the town, since a Union attack was imminent.

The public is hereby notified of the rapid approach of the enemy, but assured that the city of Columbus will be defended to the last. Judging from experience it is believed that the city will be shelled. Notice is, therefore, given to all non-combatants to move away immediately.[2]

General Howell Cobb's defense strategy

[edit]

Cobb decided to defend the city on the western (Alabama) side of the Chattahoochee, in the town of Girard (now known as Phenix City). There the Confederates used trenches, breastworks and earthen forts that had been partially built earlier in the war. Now their completion became imperative.

The main objective was to defend the two covered bridges that connected Girard to Columbus. Cobb had the advantage of knowing that Wilson would have to concentrate on these two narrow locations in order to capture Columbus. Cobb also wanted to keep the high ground in Girard out of Wilson's clutch, lest he have a convenient perch to bombard Columbus.

In addition to preparing strong fortified positions on the high ground in Girard on the west side of the Chattahoochee, Cobb ordered the base of the bridges to be wrapped in cotton and doused with turpentine. In the event that the Confederates were unable to fend off Wilson's raiders, they could, as a last resort, burn the bridges to deny Wilson's troops easy access to Columbus.

The bridges were designed by Horace King, master builder and legislator. In 1807, King was born into slavery but through hard work, he earned his freedom and became one of the most respected bridge builders in the South. Affectionately known as Horace “The Bridge Builder” King and the "Prince of Bridge Builders", he emerged from the Civil War as a legislator in the State of Alabama.[3]

The battle

[edit]Between 1:30 and 2 p.m. on Easter, April 16, 1865, Wilson's raiders arrived at Girard, and the fighting began. Wilson also sent a detachment north of Columbus to West Point, Georgia, to cross the Chattahoochee River there. West Point was defended by the garrison at Fort Tyler. The Battle of West Point and the Battle of Columbus took place on the same day.

At about 2 p.m. Union General Emory Upton's division launched an attack on the lower (southern) bridge. Meeting very little resistance, they thought they would cross the bridge and take Columbus relatively easily. Upton remarked, "Columbus is ours without a shot being fired." But this was a trap. Confederates removed the planks on the east side of the bridge to halt the Federals and allow the Confederates to burn the bridge filled with soldiers.[4][5] Recognizing the peril, Upton was forced to retreat. It seemed that the Confederates might be able to defend Columbus.

Wilson turned his attention to the upper bridge.

As the sun began to set, General Robert Toombs (CSA) telegraphed Governor Joseph E. Brown of Georgia telling him that a skirmish had occurred. He projected a "decided fight" the following day.[6] To Toombs' surprise, General Wilson launched an assault on the upper bridge at 8 p.m., after nightfall. He ordered General Winslow's brigade of the 3rd and 4th Iowa Cavalry regiments to lead the attack.[7] Colonel Frederick Benteen was ordered to lead the charge on the bridge. He later served under Custer at the Battle of Little Big Horn.[8]

A tremendous clash occurred near the entrance of the upper bridge. Confederate John Pemberton was slashed by a sabre.

Around 10 p.m. the Confederate defenses in Girard collapsed, and they attempted a retreat back across the Chattahoochee River into Georgia. At the same time, Winslow's brigade was eager to get across the upper bridge before it too might be set afire by the Confederates. Side by side, both Union and Confederate soldiers raced across the bridge to Columbus. It was too dark, however, for either to see who was who. Though attempts were made to burn the bridge, the Confederates did not want to endanger their own troops.

General Robert Toombs commanded two cannon on the Georgia side of the upper bridge. They were loaded with canister and aimed to bring down those making their way through the covered bridge. But, knowing that the soldiers running across the bridge were a mix of Union and Confederates, Toombs held his fire.

At 11 p.m. Wilson made his way across the bridge. As he crossed, his horse was shot and later died.[9] On the Columbus side of the bridge, Wilson took up headquarters in the house nearest to the bridge: the Mott House (Columbus, Georgia). There on "Mott's Green", Colonel C. A. L. Lamar led a cavalry charge. Lamar was killed after refusing to surrender to a dismounted Union cavalryman.[10] Lamar was identified by General William Tecumseh Sherman, erroneously, as the last Confederate to die in the Civil War.[11][12] Lamar was previously known for his role in underwriting the illegal voyage of Wanderer, which landed 409 Africans on Jekyll Island outside Brunswick, Georgia in 1858.

The day after

[edit]

On the morning of April 17, 1865, General Wilson ordered the destruction of all resources in Columbus that could aid the Confederate war effort. The ironclad CSS Muscogee (also known as the CSS Jackson) was burned and sunk, and the Confederate naval facility, Port Columbus, was entirely destroyed.[13] Confederates scuttled the CSS Chattahoochee to prevent it from falling into Union hands.

A review of the hospital records of the Battle of Columbus reveal the actual number of casualties incurred were considerably higher than previously reported. While the initial Union casualty list reported by General Wilson indicated a loss of 25 men during the assault, the actual number was 60. 10 of these men were killed in battle and 8 others later died of their wounds. Most of these men are buried in Andersonville National Cemetery. The Confederate casualties numbered 151, of whom many are buried in Columbus at Linwood Cemetery. Another 1,600 Confederate prisoners were rounded up and incarcerated in a makeshift Union prison camp. The Union army entirely destroyed the Confederate manufacturing facilities in both Columbus, Georgia and Girard (now Phenix City), Alabama. Collateral damage on either side of the Chattahoochee River was rather extensive as well. For days after the battle, "the flames that consumed the warehouses and factories in the Chattahoochee Valley marked the end of the war." The Union cavalry vanguard departed Columbus on the 18th of April.[13]

On to Macon and the capture of America's most wanted men

[edit]Immediately after the victory at Columbus, Wilson led his raiders east to Macon, Georgia and occupied that city without resistance. Ten days after the Battle of Columbus, the last great army of the Confederacy, under General Joseph E. Johnston, surrendered at Bennett Place, North Carolina. The American Civil War had come to an end.

In early May in central Georgia, Wilson's men apprehended the two most wanted men in America: Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy; and Captain Henry Wirz, commandant of the Confederate prison at Andersonville.

Argument that Columbus was the last battle of the Civil War

[edit]Several sources have held that this was the last battle of the war.[14][15][16][17][18] In 1935, seeking support for a national battlefield park to be established here, the Georgia state government declared this to be the "last battle of the war between the states."[19][20]

Insofar as the surrender of the bulk of Confederates on April 26, 1865, at Bennett Place, North Carolina, marked the effective end of the war (as many state governments maintained), the Battle at Columbus was the last battle of the Civil War. President Andrew Johnson, who had succeeded Lincoln, declared the war over on May 10, 1865. This was the day that President Jefferson Davis was captured. Johnson characterized remaining resisters as no longer combatants, but "fugitives."[21]

The Battle of Palmito Ranch took place on May 13. Some claim that this was the last battle of the war, rejecting President Johnson's definition and preferring to refer to the Confederates there as "organized forces" of the Confederacy.[14][22]

The officers who led Union forces in the battle insisted that Columbus was the last battle of the war. On May 30, 1865 Brevet Major General Emory Upton reported for his division in the Wilson Raid, in the Official Records, that the Battle of Columbus was the "closing conflict of the war."[23] In 1868, General Wilson gave a speech to a soldier's reunion, wherein he detailed the Battle of Columbus and concluded "the last battle had been fought."[24] In 1913 Wilson wrote that there were "no grounds left for doubting that 'Columbus was the last battle of the war.'"[25] General Edward F. Winslow wrote, "I have always considered that engagement, by the number present and the results achieved, to be the final battle of the war."[26] Colonel Theodore Allen wrote, "It is true that there was some desultory fighting and scrapping after the battle at Columbus, Georgia, but nothing of sufficient size to entitle it to the name of a battle."[27]

A movement to preserve the Girard/Columbus battlefield as a national park was active from the 1890s through the 1930s. The director of the National Park Service, Arno B. Cammerer, rejected the proposal in 1934. In response, in 1935 the Georgia state legislature passed a resolution identifying the battle as the last of the Civil War and calling again for a national battlefield park to be established there.[28]

In the 21st century, some people have begun a renewed effort to commemorate the battlefield as a park. Representatives of Auburn University posted an appeal in 2013 to help preserve Ft. Gilmer, one of the earthwork redoubts on the Alabama side of the Chattahoochee River.[29]

In 2015, Columbus State University Professor Virginia Causey addressed the topic of last battle status in an article in the local Ledger-Enquirer paper.[30] She suggested that this status was based on myth, according to a 45-page report prepared by the Department of the Interior in 1934. In 2015 Daniel Bellware rebutted her account in his article "How Columbus Lost the Last Battle of the Civil War."[31]

Bellware said that the report had numerous factual errors, has no date and credits no author calling into question its attribution to the Department of the Interior. The report argues that the engagement in Columbus, which included major generals and thousands of combatants on both sides, does not rise to the level of a battle. However, it concludes that Palmito Ranch, a much smaller engagement with colonels commanding and a few hundred combatants, should be ranked as the last battle of the war. The report refers to former Confederate President Jefferson Davis's account in his book The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. Bellware said that it might be more appropriate to rank the Battle of Columbus as “the last major military engagement of the Civil War,” to avoid the argument of whether a particular engagement qualifies as a battle.

Representation in other media

[edit]- A reenactment of the battle was filmed in Columbus, Georgia in March 1915 for the movie The Spirit of Columbus 1865-1915. [A lost film.] Several battle scenes were incorporated into a story of romance. The movie was screened during the Columbus Homecoming festivities on April 14–17, 1915 to commemorate the battle's fiftieth anniversary.

References

[edit]- ^ The Last Ditch: The Battle of Columbus, DVD

- ^ Columbus Daily Sun, April 16, 1865

- ^ J. David Dameron, Horace King: From Slave to Master Builder and Legislator, Southeast Research Publishing, LLC, Madison, Alabama, 2017.

- ^ "Confederates Set Fire to the Lower Bridge", Groundspeak

- ^ Misulia, 92–95.

- ^ Joe Brown's Army, 107.

- ^ Col. Edward Winslow, Civil War Notebook blog, January 2010

- ^ Wilson's Cavalry Corps, p. 189

- ^ J.H. Wilson, Under the Old Flag, p. 230

- ^ Archaeologists Discover Civil War Artifacts In Georgia : NPR

- ^ General Sherman to Joseph West

- ^ Savannah's Laurel Grove

- ^ a b J. David Dameron, The Battle of Columbus, April 16-17, 1865, Southeast Research Publishing, LLC, Madison, Alabama, 2017.

- ^ a b Richard Gardiner, "The Last Battle of the Civil War and Its Preservation," Journal of America's Military Past XXXVIII (Summer 2013), 5–22

- ^ Charles Misulia, Columbus, Georgia 1865: The Last True Battle of the Civil War

- ^ Journal of the Military Service Institution, Vol. 56, p. 359-375

- ^ "Daniel Bellware, "The Last Battle of the Civil War"". Archived from the original on 2017-08-02. Retrieved 2010-02-26.

- ^ Journal of the United States Cavalry Association, Vol. 18; Colonel Theodore Allen, "The Last Battle of the Civil War"

- ^ "Acts and Resolutions of the Georgia General Assembly". Archived from the original on 2021-01-29. Retrieved 2011-07-30.

- ^ In Brevet Major General Emory Upton's May 30, 1865 report for his division in the Wilson Raid, in the Official Records, he refers to the Battle of Columbus as the "closing conflict of the war." Official Records, I:49, Part One, p. 475. It is not apparent whether this is for his division only but Brevet Major General John T Croxton's division engaged in the later Battle of Munford. The Battle of Boykin's Mill, as well as the Battle of Palmito Ranch and several other small actions took place later than the Columbus Battle. But these took place after President Jefferson Davis was captured on May 10, 1865. Together with Lee's surrender, many historian consider this the end of the Confederate government and therefore, the end of the war. Other actions were taking place between forces without high-level orders.

- ^ Andrew Johnson, Proclamation, May 10, 1865

- ^ Misulia addresses the claims of the Battle of Boykin's Mill, later than Columbus but before Bennett Place, in which similar casualties were suffered, and the April 23 Battle of Munford engaged in by a division of Wilson's Raiders. Supporters of the Columbus claim do not accept the later surrender of the Trans-Mississippi Department under General E. Kirby Smith, which occurred after the Battle of Palmito Ranch, as marking the end of the war. The Columbus argument rests on the premise that when the entity at war has ceased to exist, no "war" per se, can truly exist.

- ^ Official Records, I:49, Part One, p. 475.

- ^ General James H. Wilson, 1868 Speech

- ^ Wilson to Swift, Dec. 3, 1913

- ^ Winslow to Swift, January 23, 1914

- ^ Colonel Theodore Allen, Last Battle of the Civil War

- ^ "GALILEO: Georgia Legislative Documents: Results". neptune3.galib.uga.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-01-29. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- ^ "Fort No. 5: An Endangered Piece of History « Chattahoochee Heritage". www.chattahoocheeheritage.org. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- ^ "The last battle?". Ledger-Enquirer. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- ^ Daniel Bellware, "How Columbus Lost the Last Battle of the Civil War," Muscogiana, Columbus, GA: Columbus State University, Spring 2015

Sources

[edit]- J. David Dameron, "The Battle of Columbus, April 16-17, 1865", Southeast Research Publishing, LLC, 2017

- Charles A. Misulia, Columbus, Georgia, 1865: The Last True Battle of the Civil War Archived 2013-03-15 at the Wayback Machine, University of Alabama Press, 2010

- Richard Gardiner, "The Last Battle of the Civil War and Its Preservation", Journal of America's Military Past XXXVIII (Spring/Summer 2013), pp. 5–22.

- J. David Dameron, "Horace King: From Slave to Master Builder and Legislator", Southeast Research Publishing, LLC, 2017

- Charles Jewett Swift, "The Last Battle of the Civil War at Columbus, Georgia", Journal of the Military Service Institution, Vol. 56, p. 359

- James Pickett Jones "Yankee Blitzkrieg: Wilson's Raid Through Alabama and Georgia", University of Georgia Press, 1976, pp. 126–144.

- Daniel Bellware, "The Last Battle. Period. Really.", Civil War Times Illustrated Vol. 42, April 2003.

External links

[edit]- Charles Swift, "The Last Battle of the Civil War", Rootsweb

- "The Battle of Columbus", WRBL News Report

- "The Last Ditch", a video produced by Jim Bridges

- "The Battle of Columbus", Explore Southern History.com

- Battle of Columbus in Photos, Civil War Album

- "The Last True Battle of The Civil War" —Presentation, Muscogee Genealogy Society

- Alva C. Smith Collection, Columbus State University Archives (Box 39 includes correspondence related to request for a monument)

KSF

KSF