Battle of Hakodate

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

| Battle of Hakodate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Boshin War | |||||||

Battle of Hakodate, William Henry Webster | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

7,000 1 steam ironclad 9 steam warships |

3,000 11 steam warships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

770 killed and wounded 1 steam warship sunk 1 steam warship destroyed |

1,700 killed and wounded 1,300 captured 2 steam warships sunk 3 steam warships destroyed 3 steam warships captured | ||||||

Location within Hokkaido | |||||||

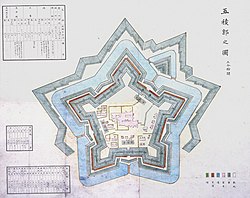

The Battle of Hakodate (箱館戦争, Hakodate Sensō) was fought in Japan from December 4, 1868 to June 27, 1869, between the remnants of the Tokugawa shogunate army, consolidated into the armed forces of the rebel Ezo Republic, and the armies of the newly formed Imperial government (composed mainly of forces of the Chōshū and the Satsuma domains). It was the last stage of the Boshin War, and occurred around Hakodate in the northern Japanese island of Hokkaidō. In Japanese, it is also known as the Battle of Goryokaku (五稜郭の戦い, Goryokaku no tatakai).

Background

[edit]The Boshin War erupted in 1868 between troops favorable to the restoration of political authority to the Emperor and the government of the Tokugawa shogunate. The Meiji government defeated the forces of the Shōgun at the Battle of Toba–Fushimi and subsequently occupied the Shōgun's capital at Edo.

Enomoto Takeaki, vice-commander of the Shogunate Navy, refused to remit his fleet to the new government and departed Shinagawa on August 20, 1868, with four steam warships (Kaiyō, Kaiten, Banryū, Chiyodagata) and four steam transports (Kanrin Maru, Mikaho, Shinsoku, Chōgei) as well as 2,000 sailors, 36 members of the "Yugekitai" (guerilla corps) headed by Iba Hachiro, several officials of the former Bakufu government including the vice-commander in chief of the Shogunate Army Matsudaira Taro, Nakajima Saburozuke, and members of the French Military Mission to Japan, headed by Jules Brunet.

On August 21, the fleet encountered a typhoon off Chōshi, in which Mikaho was lost and Kanrin Maru, heavily damaged, forced to turn back, where she was captured at Shimizu.

The rest of the fleet reached Sendai harbor on August 26, one of the centers of the Northern Coalition (奥羽越列藩同盟) against the new government, composed of the fiefs of Sendai, Yonezawa, Aizu, Shōnai and Nagaoka.

Imperial troops continued to progress north, taking the castle of Wakamatsu, and making the position in Sendai untenable. On October 12, 1868, the fleet left Sendai, after having acquired two more ships (Ōe and the Hōō, previously borrowed by Sendai Domain from the Shogunate), and about 1,000 more troops: former Bakufu troops under Ōtori Keisuke, Shinsengumi troops under Hijikata Toshizō, and Yugekitai under Katsutaro Hitomi, as well as several more French advisors (Fortant, Marlin, Bouffier, Garde), who had reached Sendai overland.

Battle

[edit]Occupation of southern Hokkaidō

[edit]The rebels, numbering around 3,000 and traveling by ship with Enomoto Takeaki reached Hokkaidō in October 1868. They landed on Washinoki Bay, behind Hakodate on October 20. Hijikata Toshizo and Otori Keisuke each led a column in the direction of Hakodate. They eliminated local resistance by forces of Matsumae Domain, which had declared its loyalty to the new Meiji government, and occupied the fortress of Goryōkaku on October 26, which became the command center for the rebel army.

Various expeditions were organized to take full control of the southern peninsula of Hokkaidō. On November 5, Hijikata, commanding 800 troops and supported by the warships Kaiten and Banryo, occupied the castle of Matsumae. On November 14, Hijikata and Matsudaira converged on the city of Esashi, with the added support of the flagship Kaiyo Maru, and the transport ship Shinsoku. Kaiyō Maru was shipwrecked and lost in a tempest near Esashi, and Shinsoku also was lost as it came to its rescue, dealing a terrible blow to the rebel forces.

After eliminating all local resistance, on December 25, the rebels founded the Ezo Republic, with a government organization modeled after that of the United States, with Enomoto Takeaki, as President (総裁). The Meiji government in Tokyo refused to recognise the breakaway republic.

A defense network was established around Hakodate in anticipation of the attack by the troops of the new Imperial government. The Ezo Republic troops were structured under a hybrid Franco-Japanese leadership, with Commander in chief Ōtori Keisuke seconded by Jules Brunet, and each of the four brigades commanded by a French officer (Fortant, Marlin, André Cazeneuve, Bouffier), seconded by eight half-brigade Japanese commanders. Two ex-French Navy officers, Eugène Collache and Henri Nicol, also joined the rebels, and Collache was put in charge of building fortified defenses along the volcanic mountains around Hakodate, while Nicol was in charge of re-organizing the Navy.

In the meantime, an Imperial fleet had been rapidly constituted around the ironclad warship Kōtetsu, which had been purchased by the Meiji government from the United States. Other Imperial ships were Kasuga, Hiryū, Teibō, Yōshun, and Mōshun, which had been supplied by the fiefs of Saga, Chōshū and Satsuma to the newly formed government in 1868. The fleet left Tokyo on March 9, 1869, and headed north.

Miyako Bay

[edit]

The Imperial navy reached the harbor of Miyako on March 20. Anticipating the arrival of the Imperial fleet, the rebels organized a daring plan to seize the powerful new warship Kōtetsu.

Three warships were dispatched for a surprise attack, in what is known as the Battle of Miyako Bay: the Kaiten, on which were riding the elite Shinsengumi as well as the ex-French Navy officer Henri Nicol, the warship Banryu, with the ex-French officer Clateau, and the warship Takao, with ex-French Navy officer Eugène Collache on board. To create surprise, the Kaiten entered Miyako harbor with an American flag. They raised the Ezo Republic flag seconds before boarding the Kōtetsu. The crew of Kōtetsu managed to repel the attack with a Gatling gun, with huge losses to the attackers. The two Ezo warships escaped back to Hokkaidō, but the Takao was pursued and beached itself.

Landing of Imperial forces

[edit]The Imperial troops, numbering 7,000, finally landed on Hokkaidō on April 9, 1869. They progressively took over various defensive positions, until the final stand occurred around the fortress of Goryōkaku and Benten Daiba around the city of Hakodate.

Japan's first major naval engagement between two modern navies, the Naval Battle of Hakodate Bay, occurred towards the end of the conflict, during the month of May 1869.[1]

Before the final surrender, in June 1869, the Ezo Republic French military advisors escaped to a French Navy warship stationed in Hakodate Bay, the Coëtlogon, from where they returned to Yokohama and thence to France.

After having lost close to half their numbers and most of their ships, the military of Ezo Republic surrendered to the Meiji government on June 27, 1869.

Aftermath

[edit]

The battle marked the end of the old feudal regime in Japan, and the end of armed resistance to the Meiji Restoration. After a few years in prison, several of the leaders of the rebellion were rehabilitated, and continued with brilliant political careers in the new unified Japan: Enomoto Takeaki in particular took various ministry functions during the Meiji period.

The new Imperial government, finally secure, established numerous new institutions soon after the end of the conflict. The Imperial Japanese Navy in particular was formally established in July 1869, and incorporated many of the combatants and ships which had participated in the Battle of Hakodate.

The future admiral Tōgō Heihachirō, hero of the 1905 Battle of Tsushima, participated in the battle as a gunner on board the paddle steam warship Kasuga.

Later depictions of the battle

[edit]Although the Battle of Hakodate involved some of the most modern armament of the era (steam warships, and even an ironclad warship, barely invented 10 years earlier with the world's first seagoing ironclad, the French La Gloire), Gatling guns, Armstrong guns, modern uniforms and fighting methods, most of the later Japanese depictions of the battle during the few years after the Meiji Restoration offer an anachronistic representation of traditional samurai fighting with their swords, possibly in an attempt to romanticize the conflict, or to downplay the amount of modernization already achieved during the Bakumatsu period (1853–1868).

Significance

[edit]Modernization

[edit]Although the modernization of Japan is generally explained as starting with the Meiji period (1868), it actually started significantly earlier from around 1853 during the final years of the Tokugawa shogunate (the Bakumatsu period). The 1869 Battle of Hakodate shows two sophisticated adversaries in an essentially modern conflict, where steam power and guns play the key role, although some elements of traditional combat clearly remained. A great deal of Western scientific and technological knowledge had already been entering Japan since around 1720 through rangaku, the study of Western sciences, and since 1853, the Tokugawa shogunate had been extremely active at modernizing the country and opening it to foreign influence. In a sense, the Restoration movement, based on the sonnō jōi ideology was a reaction to this modernization and internationalization, although, in the end, the Meiji Emperor chose to follow a similar policy under the Fukoku kyōhei ("rich country, strong army") principle. Some of his former supporters from Satsuma, such as Saigō Takamori would revolt against this situation, leading to the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877.

French involvement

[edit]A group of French military advisors, members of the 1st French Military Mission to Japan and headed by Jules Brunet, fought side-by-side with troops of the former Tokugawa bakufu, whom they had trained during 1867–1868.

The Battle of Hakodate also reveals a period of Japanese history when France was strongly involved with Japanese affairs. Similarly, the interests and actions of other Western powers in Japan were quite significant, but to a lesser extent than with the French. This French involvement is part of the broader, and often disastrous, foreign activity of the French Empire under Napoleon III, and followed the campaign of Mexico. The members of the French Mission who followed their Japanese allies to the North all resigned or deserted from the French Army before accompanying them. Although they were speedily rehabilitated upon their return to France, and some, such as Jules Brunet continued illustrious careers, their involvement was not premeditated or politically guided, but rather a matter of personal choice and conviction. Although defeated in this conflict, and again defeated in the Franco-Prussian War, France continued to play an important role in Japan's modernization: a Second Military Mission was invited in 1872, and the first true modern fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy was built under the supervision of the French engineer Émile Bertin in the 1880s.

See also

[edit]References and notes

[edit]- ^ Lesser preceding actions were the Battle of Shimonoseki Straits (1863) and Battle of Awa (1868).

- Hillsborough, Romulus (2005). Shinsengumi: The Shogun's Last Samurai Corps. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3627-2.

KSF

KSF