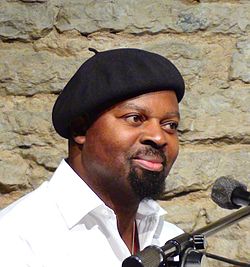

Ben Okri

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 18 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 18 min

Ben Okri | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Ben Golden Emuobowho Okri 15 March 1959 Minna, Nigeria |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | Nigeria UK |

| Genre | Fiction, essays, poetry |

| Literary movement | Postmodernism, Postcolonialism |

| Notable works | The Famished Road (1991), A Way of Being Free (1997), Starbook (2007), A Time for New Dreams (2011) |

| Notable awards | Booker Prize 1991 |

| Website | |

| benokri | |

Sir Ben Golden Emuobowho Okri OBE FRSL (born 15 March 1959) is a Nigerian-born British poet and novelist.[1] Considered one of the foremost African authors in the postmodern and post-colonial traditions,[2][3] Okri has been compared favourably to authors such as Salman Rushdie and Gabriel García Márquez.[4] In 1991, his novel The Famished Road won the Booker Prize.[5] Okri was knighted at the 2023 Birthday Honours for services to literature.[6]

Biography

[edit]Early years and education

[edit]Ben Okri is a member of the Urhobo people; his father was Urhobo, and his mother was half-Igbo ("from a royal family").[1][7] He was born in Minna in west central Nigeria to Grace and Silver Okri in 1959.[7] His father, Silver, moved his family to London, England, when Okri was less than two years old[3] so that he could study law.[8] Okri thus spent his earliest years in London and attended primary school in Peckham.[2] In 1966, Silver moved his family back to Nigeria,[9] where he practised law in Lagos, providing free or discounted services for those who could not afford it.[7] After attending schools in Ibadan and Ikenne, Okri began his secondary education at Urhobo College at Warri,[10][11] in 1968, when he was the youngest in his class.[9] His exposure to the Nigerian civil war[12] and a culture in which his peers at the time claimed to have had visions of spirits[3] provided inspiration for Okri's fiction.

At the age of 14, after being rejected for admission to a short university programme in physics because of his youth and lack of qualifications, Okri experienced a revelation that poetry was his chosen calling.[13] He began writing articles on social and political issues, but these never found a publisher.[13] He then wrote short stories based on those articles, and some were published in women's journals and evening papers.[13] Okri has said that his criticism of the government in some of this early work led to his name being placed on a death list, and necessitated his departure from the country.[3]

Move to England, 1978

[edit]In 1978, he moved back to England and studied comparative literature at Essex University with a grant from the Nigerian government.[14][13] But when funding for his scholarship fell through, Okri found himself homeless, sometimes living in parks and sometimes with friends. He has called this period "very, very important" to his work: "I wrote and wrote in that period... If anything [the desire to write] actually intensified."[13]

Okri's success as a writer began when he published his debut novel, Flowers and Shadows, in 1980, at the age of 21.[1] From 1983 to 1986, he served as poetry editor of West Africa magazine,[9] and he regularly contributed to the BBC World Service between 1983 and 1985, continuing to publish throughout this period.[1]

His reputation as an author was secured when his novel The Famished Road won the Booker Prize for Fiction in 1991,[1][15] making him the prize's youngest ever winner at 32.[16] The novel was written during the time from 1988 that Okri lived in a Notting Hill flat that he rented from publisher friend Margaret Busby,[17][18] and he has said:

- "Something about my writing changed round about that time. I acquired a kind of tranquillity. I had been striving for something in my tone of voice as a writer—it was there that it finally came together.... That flat is also where I wrote the short stories that became [1988's] Stars of the New Curfew."[14]

In 1997, Okri was elected vice-president of the English Centre for International PEN and in 1999 was appointed a member of the board of the Royal National Theatre.[1][19]

On 26 April 2012, he was appointed vice-president of the Caine Prize for African Writing, having been on the advisory committee and associated with the prize since it was established 13 years earlier.[20]

Okri was appointed as a vice-president of the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama in 2022.[21]

Literary career

[edit]

Since the 1980 publication of Flowers and Shadows, Okri has risen to international acclaim, and he often is described as one of Africa's leading writers.[2][3]

His best known work, The Famished Road, which won the 1991 Booker Prize,[22] along with Songs of Enchantment (1993)[23][24] and Infinite Riches (1998) make up a trilogy that follows Azaro, a spirit-child narrator, through the social and political turmoil of an African nation reminiscent of Okri's remembrance of war-torn Nigeria.[1]

Okri's work is particularly difficult to categorise. It has been widely called postmodern,[25] but some scholars have noted that the seeming realism with which he depicts the spirit-world challenges this categorisation. If Okri does attribute reality to a spiritual world, it is claimed, then his "allegiances are not postmodern [because] he still believes that there is something ahistorical or transcendental conferring legitimacy on some, and not other, truth-claims."[25] Alternative characterisations of Okri's work suggest an allegiance to Yoruba folklore,[26] New Ageism,[25][27] spiritual realism,[27] magical realism,[28] visionary materialism,[28] and existentialism.[29]

Against these analyses, Okri has always rejected the categorisation of his work as magical realism, claiming that this categorisation is the result of laziness by critics and likening it to the observation that "a horse ... has four legs and a tail. That doesn't describe it."[3] He has instead described his fiction as obeying a kind of "dream logic"[12] and said that it is often preoccupied with the "philosophical conundrum ... what is reality?"[13] insisting that:

- I grew up in a tradition where there are simply more dimensions to reality: legends and myths and ancestors and spirits and death ... Which brings the question: what is reality? Everyone's reality is different. For different perceptions of reality we need a different language. We like to think that the world is rational and precise and exactly how we see it, but something erupts in our reality which makes us sense that there's more to the fabric of life. I'm fascinated by the mysterious element that runs through our lives. Everyone is looking out of the world through their emotion and history. Nobody has an absolute reality.[12]

Okri has noted the effect of personal choices: "Beware of the stories you read or tell; subtly, at night, beneath the waters of consciousness, they are altering your world."[30]

As well as novels, Okri's published books include collections of poetry, essays and short stories. His short fiction has been described as more realistic and less fantastic than his novels, but it also depicts Africans in communion with spirits,[1] while his poetry and nonfiction have a more overt political tone, focusing on the potential of Africa and the world to overcome the problems of modernity.[1][31]

Okri has also written plays and film scripts, such as the text to Peter Krüger's film N – The Madness of Reason, which won the 2015 Ensor Award for Best Film.[32] In 2018, Okri adapted Albert Camus's novella The Outsider as a play for the Print Room at The Coronet Theatre.[33]

In April 2019, Okri gave the keynote address at the second Berlin African Book Festival, curated by Tsitsi Dangarembga.[34]

Okri's volume of collected poems, A Fire in My Head: Poems for the Dawn, was published in 2021, its title inspired by a line in Wole Soyinka's poem "Death in the Dawn": "May you never walk / when the road waits, famished."[35]

Alongside his writing, Okri has maintained an interest in visual art since his youth, and in 2023, he collaborated with colourist painter Rosemary Clunie in Firedreams, at the Bomb Factory, Marylebone, an exhibition of "WordArt" that featured large-scale paintings and sculptural obstructions.[36][37] Okri and Clunie, his long-time friend, had previously brought together their paintings and stories in the 2017 book The Magic Lamp: Dreams of Our Age.[32][38]

Influences

[edit]Okri has described his work as influenced as much by the philosophical texts on his father's bookshelves as by literature,[13] and cites the influence of Francis Bacon and Michel de Montaigne on his A Time for New Dreams.[39] His literary influences include Aesop's Fables, Arabian Nights, Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream,[12] and Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.[13] Okri's 1999 epic poem, Mental Fight, is named after a quotation from the poet William Blake's "And did those feet ...",[40] and critics have noted a close relationship between Blake and Okri's poetry.[28]

Okri also was influenced by the oral tradition of his people and, particularly, by his mother's storytelling: "If my mother wanted to make a point, she wouldn't correct me, she'd tell me a story."[12] His firsthand experiences of civil war in Nigeria are said to have inspired many of his works.[12]

On the final day of the 2021 COP26 climate meeting in Glasgow, Okri wrote about the existential threat posed by the climate crisis and how ill‑equipped humans seem to confront the prospect of their self-inflicted extinction. Indeed, Okri says: "We have to find a new art and a new psychology to penetrate the apathy and the denial that are preventing us making the changes that are inevitable if our world is to survive."[41]

Honours and awards

[edit]Okri was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2001 Birthday Honours for services to literature[42][43] and knighted in the 2023 Birthday Honours, also for services to literature.[44]

- 1987: Commonwealth Writers Prize (Africa Region, Best Book) – Incidents at the Shrine[45]

- 1987: Aga Khan Prize for Fiction – The Dream Vendor's August[46]

- 1988: Guardian Fiction Prize – Stars of the New Curfew (shortlisted)[47]

- 1991–1993: Fellow Commoner in Creative Arts (FCCA), Trinity College, Cambridge[48]

- 1991: Booker Prize – The Famished Road[49]

- 1993: Chianti Ruffino-Antico Fattore International Literary Prize – The Famished Road[50]

- 1994: Premio Grinzane Cavour (Italy) -The Famished Road[45]

- 1995: Crystal Award (World Economic Forum)[51]

- 1997: Honorary Doctorate of Literature, awarded by University of Westminster[52]

- 1997: Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature[53]

- 1999: Premio Palmi (Italy) – Dangerous Love[54]

- 2002: Honorary Doctorate of Literature, awarded by University of Essex[55]

- 2003: Chosen as one of 100 Great Black Britons[56]

- 2004: Honorary Doctor of Literature, awarded by University of Exeter[57]

- 2008: International Literary Award Novi Sad (International Novi Sad Literature Festival, Serbia)[58]

- 2009: Honorary Doctorate of Utopia, awarded by Universiteit voor het Algemeen Belang, Belgium[59]

- 2010: Honorary Doctorate, awarded by the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London[60]

- 2010: Honorary Doctorate of Arts, awarded by the University of Bedfordshire[61]

- 2014: Honorary Doctorate from the University of Pretoria[62][63]

- 2014: Honorary Fellow, Mansfield College, Oxford[64]

- 2014: Bad Sex in Fiction Award, Literary Review[65][66]

- 2020: Honorary Doctorate of Literature awarded by Nelson Mandela University[67]

Works

[edit]Novels

[edit]- Flowers and Shadows (Harlow: Longman, 1980)[68]

- The Landscapes Within (Harlow: Longman, 1981)[69]

- The Famished Road (London: Jonathan Cape, 1991)[70]

- Songs of Enchantment (London: Jonathan Cape, 1993)[71]

- Astonishing the Gods (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995)[72]

- Dangerous Love (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1996)[73]

- Infinite Riches (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1998)[74]

- In Arcadia (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2002)[75]

- Starbook (London: Rider Books, 2007)[7]

- The Age of Magic (London: Head of Zeus, 2014)[76]

- The Freedom Artist (London: Head of Zeus, 2019)[77]

- Every Leaf a Hallelujah (London: Head of Zeus, 2021)[78]

- The Last Gift of the Master Artists (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022)[79]

Poetry, essays and short story collections

[edit]- Incidents at the Shrine (short stories; London: Heinemann, 1986)[80]

- Stars of the New Curfew (short stories; London: Secker & Warburg, 1988)[81]

- An African Elegy (poetry; London: Jonathan Cape, 1992)[82]

- Birds of Heaven (essays; London: Phoenix House, 1996)[83]

- A Way of Being Free (essays; London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson: 1997; London: Phoenix House, 1997)[84]

- Mental Fight (poetry: London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1999; London: Phoenix House, 1999)[85]

- Tales of Freedom (short stories; London: Rider & Co., 2009)[86]

- A Time for New Dreams (essays; London: Rider & Co., 2011)[87]

- Wild (poetry; London: Rider & Co., 2012)[88]

- The Mystery Feast: Thoughts on Storytelling (West Hoathly: Clairview Books, Ltd, 2015)[89]

- The Magic Lamp: Dreams of Our Age, with paintings by Rosemary Clunie (Apollo/Head of Zeus, 2017)[90][91]

- Prayer for the Living: Stories (London: Head of Zeus, 2019)[92][93]

- A Fire in My Head: Poems for the Dawn (London: Head of Zeus, 2021)[94][95]

- Tiger Work (London: Apollo, an imprint of Head of Zeus, 2023)[96]

As editor

[edit]- Rise Like Lions: Poetry for the Many (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2018, ISBN 9781473676152)[97][98]

- African Stories (London: Everyman's Library Pocket Classics, 2025, ISBN 9781841596372)[99]

Film

[edit]- N – The Madness of Reason (feature film, directed by Peter Krüger, 2014)[100]

Online fiction

[edit]- "A Wrinkle In The Realm". The New Yorker. 1 February 2021.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Ben Okri", British Council, Writers Directory. Archived 2 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c "Ben Okri", Editors, The Guardian, 22 July 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Anrys, Stefaan (26 August 2009). "Interview with Booker Prize laureate Ben Okri". Mondiaal Nieuws.

- ^ Dorsman, Robert (2000), "Ben Okri", Poetry International Web. Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Ben Okri | The Booker Prizes". thebookerprizes.com. 15 March 1959. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Davies, Caroline (16 June 2023). "Martin Amis, Ian McEwan and Anna Wintour honoured in king's birthday list". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d Jaggi, Maya (10 August 2007). "Free spirit". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Rix, Juliet (25 June 2010). "Ben Okri: My family values". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c Frailey, Paul (28 December 2011). "Ben Okri (1959–)". BlackPast. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (11 March 2021). "Ben Okri". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Ben Okri profile, The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d e f Sethi, Anita (1 September 2011). "Ben Okri: novelist as dream weaver". TheNational.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Interview: Ben Okri – Booker prize-winning novelist and poet", The Scotsman, 5 March 2010.

- ^ a b Venning, Nicola (3 August 2014). "Time and place: Ben Okri". The Sunday Times.

- ^ "Ben Okri: 'The Famished Road was written to give myself reasons to live'", The Guardian, 15 March 2016.

- ^ "Ben Okri", The Cultural Frontline, BBC World Service, 1 May 2016.

- ^ Davies, Paul (1 February 2023). "Video Interview | 'You do this or you die': how Ben Okri wrote The Famished Road". The Booker Prizes. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ Okri, Ben (20 May 2023). "How I wrote the Famished Road". The Sun. Nigeria.

- ^ Tunca, Daria (2011). "Okri, Ben (1959- )". In Gates Jr, Henry Louis; Emmanuel K. Akyeampong (eds.). Dictionary of African Biography (PDF). Vol. 5: Oding-Teres. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 23–25.

- ^ Allen, Katie (26 April 2012). "Okri made Caine Prize vice-president". The Bookseller.

- ^ "Central announces its new Vice Presidents". The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama. 28 November 2022. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "The Booker Prizes Backlist | The Booker Prizes". thebookerprizes.com. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "Songs of Enchantment". Publishers Weekly. 30 August 1993. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ "Songs of Enchantment". Kirkus Reviews. 15 July 1993. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ a b c McCabe, Douglas (2005). "'Higher Realities': New Age Spirituality in Ben Okri's The Famished Road." Research in African Literatures, vol. 36, no. 4, 1–21.

- ^ Quayson, Ato (1997), Transformations in Nigerian Writing (Oxford: James Currey).

- ^ a b Appiah, Anthony K. (3–10 August 1992), "Spiritual Realism". Review of The Famished Road, by Ben Okri. The Nation, 146–148.

- ^ a b c Green, Matthew J. A. (2009), "Dreams of Freedom: Magical Realism and Visionary Materialism in Okri and Blake", Romanticism, vol. 15, no. 1, 18–32.

- ^ Obumselu, Ben (2011), "Ben Okri's The Famished Road: A Re-Evaluation." Tydskrif vir Letterkunde, vol. 48, no. 1, 26–38.

- ^ "A Thought for Today ... Ben Okri", Wordsmith.org, 15 March 2017.

- ^ Okri, Ben, "A Time for New Dreams", an interview with Claire Armitstead, RSA. London, 4 April 2011. Archived 19 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b "Poet, Novelist, Artist". benokri.co.uk.

- ^ "Ben Okri | Fellow". Society of Authors. Retrieved 14 December 2024.

- ^ Murua, James (9 April 2019). "A snapshot of the African Book Festival 2019 in Berlin, Germany". James Murua's Literature Blog. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- ^ O' Malley, JP (9 December 2022). "Nigeria's Ben Okri: 'At its best, poetry draws our attention away from smallness'". The Africa Report.

- ^ "Firedreams, Ben Okri and Rosemary Clunie - Bomb Factory Marylebone". The Bomb Factory. The Bomb Factory Art Foundation. 17 March 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ "'Ben Okri & Rosemary Clunie: firedreams' at The Bomb Factory, London". Lisson Gallery London. 22 March 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ Okri, Ben (21 March 2023). "Ben Okri on swapping novels for painting: 'Could these two great rivers of creativity merge?'". The Guardian.

- ^ Vogel, Saskia (7 April 2011). "Interview: Ben Okri". Granta Magazine.

- ^ Okri, Ben (1999), Mental Fight: An Anti-Spell for the 21st Century (London: Phoenix House), 1.

- ^ Okri, Ben (12 November 2021). "Artists must confront the climate crisis – we must write as if these are the last days". The Guardian. London, United Kingdom. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Ben Okri: A writer honoured". BBC News. 13 June 2001. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ "Ben Okri features in Glo/CNN African Voices". Vanguard News. 24 June 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "No. 64082". The London Gazette (Supplement). 17 June 2023. p. B2.

- ^ a b "Ben Okri | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ "Acclaimed Author – Ben Okri". The London Nigerian - Community News and Events for Nigerians in UK. 16 September 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Flood, Alison (13 February 2012). "Ben Okri erupts at editor over 'rewriting' claim". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Creative Arts Fellowship marks 50 years". Trinity College, Cambridge. 21 September 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "The Famished Road | The Booker Prizes". thebookerprizes.com. January 1991. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Ben Okri - Literature". literature.britishcouncil.org. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Ben Okri". www.penguin.co.uk. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Aghadiuno, Eric. "Ben Okri - OnlineNigeria.com". onlinenigeria.com. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Okri, Ben". Royal Society of Literature. 1 September 2023. Retrieved 30 June 2025.

- ^ "UniVerse :: A United Nations of Poetry :: Ben Okri". www.universeofpoetry.org. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Honorary Graduates - Honorary Graduates - University of Essex". www1.essex.ac.uk. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ 100 Great Black Britons Archived 24 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine website.

- ^ "Ben Okri". CCCB. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Novi Sad International Literature Festival - Literature Across Frontiers". www.lit-across-frontiers.org. 27 August 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Honorary Degree in Utopia for Ben Okri - Antwerp, Belgium 2010", YouTube, 10 March 2015.

- ^ "SOAS Awards Honorary Doctorate to Mr Ben Okri OBE". www.soas.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "About Ben Okri | Awards and honours". benokri.co.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2025.

- ^ "South African university honours Nigerian author, Ben Okri". Vanguard News. 23 April 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ "Nigerian writer,Ben Okri to be honoured by South African varsity". PM News. Nigeria. 23 April 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2025.

- ^ "Booker Prize-winning author in conversation for Ken Hom annual lecture - Oxford Brookes University". www.brookes.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Beckman, Jonathan (December 2014). "Twitching Fairy Penguin". Literary Review'.

- ^ "Bad Sex in Fiction: Ben Okri scoops 2014 prize", BBC News, 3 December 2014.

- ^ "Ben Okri 2020 | Doctor of Literature (Honoris Causa)". Nelson Mandela University. Retrieved 3 May 2025.

- ^ Okri, Ben. (1989) [1980]. Flowers and shadows. Longman. ISBN 0-582-03536-8. OCLC 1043417403.

- ^ "The Ben Okri Bibliography: Primary Sources". www.cerep.ulg.ac.be. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Nigerian Wins British Fiction Award". The New York Times. 23 October 1991. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Taylor, Paul (21 March 1993). "BOOK REVIEW / Dreams of a boy on earth: 'Songs of Enchantment' - Ben Okri: Cape, 14.99 pounds". The Independent.

- ^ "Ben Okri, Writer, Author, Nigeria Personality Profiles". www.nigeriagalleria.com. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Dangerous Love. Bloomsbury | House of Zeus. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ "Ben Okri: A Selective Bibliography". Callaloo. 38 (5): 1004–1005. 2015. doi:10.1353/cal.2015.0165. ISSN 1080-6512.

- ^ Hickling, Alfred (12 October 2002). "Review: In Arcadia by Ben Okri". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "Author Okri receives bad sex prize". BBC News. 3 December 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Merritt, Stephanie. "Book of the day | The Freedom Artist by Ben Okri review – wake-up call of a world without books". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ Ellingham, Miles (18 December 2021). "Every Leaf a Hallelujah by Ben Okri — a plea from the forest". Financial Times. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ^ Okri, Ben (31 January 2023). The Last Gift of the Master Artists. Other Press, LLC. ISBN 978-1-63542-279-5.

- ^ "Ben Okri: A Selective Bibliography". Callaloo. 38 (5). Project MUSE: 1004–1005. 2015. doi:10.1353/cal.2015.0165. ISSN 1080-6512.

- ^ Alleyne, Richard (11 February 2012). "Ben Okri 'disappointment' at editor he claims re-wrote his work". Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ mjs76. "Visiting Professor - Ben Okri OBE FRSL — University of Leicester". www2.le.ac.uk. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Gray, Rosemary (1 July 2018). "Ben Okri's Aphorisms: "Music on the Wings of a Soaring Bird"". Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies. 7 (2): 17–24. doi:10.2478/ajis-2018-0042. hdl:2263/71561.

- ^ A Way of Being Free. Head of Zeus. 9 October 2014. ISBN 9781784081843.

- ^ Hattersley, Roy (21 August 1999). "A man in two minds". The Guardian.

- ^ Daniel, Lucy (30 April 2009). "Tales of Freedom by Ben Okri: review". Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ "The Ben Okri Bibliography: On the Internet". www.cerep.ulg.ac.be. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Birat, Kathie (2015). "'Through a Bending Light': Ben Okri's Poetic Commitment". Commonwealth Essays and Studies. 38 (1): 45–55. doi:10.4000/ces.4959. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Okri, Ben (4 November 2015). "Under the Sun: a meditation by Ben Okri on stories". The Irish Times.

- ^ Coughlan, Philipa (1 February 2019). "The Magic Lamp: Dreams of Our Age by Ben Okri". NB Magazine. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Swirsky, Rebecca (10 March 2018). "Ben Okri's The Magic Lamp is a collection of morally ambiguous tales for our trying times". New Statesman. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Prayer for the Living. Head of Zeus.

- ^ Oloko, Babi (2 February 2021). "The Immensity of Brevity: On Ben Okri's 'Prayer for the Living'". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Hackett, Tamsin (1 July 2020). "Ben Okri's first poetry collection in eight years goes to Head of Zeus". The Bookseller.

- ^ Peterson, Angeline (15 January 2021). "Ben Okri's First Poetry Collection in Nine Years is Out Now". Brittle Paper. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ "Tiger Work by Ben Okri: 9781635423365 | PenguinRandomHouse.com: Books". PenguinRandomhouse.com. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Rise Like Lions". Hodder & Stoughton.

- ^ Jackson, Jeff (September 2018). "Books | Rise Like Lions: Poetry for the Many". Socialist Review (438). Retrieved 3 May 2025.

- ^ "African Stories". penguin.co.uk. Penguin Random House. Retrieved 3 May 2025.

- ^ "N – The Madness of Reason", Blinkerfilm, 9 March 2015. Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

Further reading

[edit]- Irene, Michael Oshoke. 2015. Re-inventing oral tradition in Ben Okri's trilogy : The Famished Road, Songs of Enchantment and Infinite Riches. Anglia Ruskin University, doctoral dissertation.

- Abdelghany, Réhab, "A Question of Power: Ben Okri's 'Meditations on Greatness' at Africa Writes", Africa in Words, 24 August 2015.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Ben Okri's AALBC.com Author Profile

- Ben Okri's official Facebook Page

- Ben Okri's MySpace page

- Ben Okri's official page on the Booker Prizes website.

- Full length You Tube video of Ben Okri winning the 1991 Booker Prize.

- The Ben Okri Bibliography – an extensive bibliography of works by and about Okri, also including a short biography and an introduction to his work.

Interviews

[edit]- Audio: Ben Okri in conversation on the BBC World Service discussion programme The Forum, 19 July 2009.

- Ben Okri on RSA Audio, 4 April 2011.

- Simon Joseph Jones, "Soul Man | Ben Okri" (interview), High Profiles, 31 October 2002.

- Ben Okri: transcript of interview for the Why Are We Here? documentary series.

- "Ben Okri on the Strange Magic of Our Preoccupations". In Conversation with Mitzi Rapkin on the First Draft Podcast; via Literary Hub, February 8, 2021.

Selected poems

[edit]- "O That Abstract Garden", a poem by Ben Okri. Archived 12 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- "The Awakening Age", on the line millennium poem by Okri.

- "Poetic tribute to England clash", BBC News, 11 June, 2002. "Draw" – a poem written by Okri to mark the England World Cup match with Nigeria.

- "40 Artists, 40 Days", Tate, 2012. "Lines in Potentis", a poem by Okri. Archived 14 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Children of the Dream", The Guardian, 21 August 2003 – a poem by Okri celebrating the 40th anniversary of Martin Luther King's "I have a dream" speech.

- "Dancing With Change" (Ode Wire, April 2007 issue), a poem by Ben Okri.

- "I sing a new freedom" (Ebury Publishing, 3 April 2009), a poem by Ben Okri.

- "As clouds pass above our heads..." (Ebury Publishing, 2 February 2010), a poem by Ben Okri.

KSF

KSF