Benign prostatic hyperplasia

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 38 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 38 min

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Benign enlargement of the prostate (BEP, BPE), adenofibromyomatous hyperplasia, benign prostatic hypertrophy,[1] benign prostatic obstruction[1] |

| |

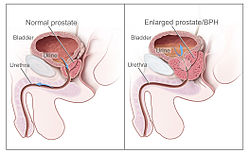

| Diagram of a normal prostate (left) and benign prostatic hyperplasia (right) | |

| Specialty | Urology |

| Symptoms | Frequent urination, trouble starting to urinate, weak stream, inability to urinate, loss of bladder control[1] |

| Complications | Urinary tract infections, bladder stones, kidney failure[2] |

| Usual onset | Age over 40[1] |

| Causes | Unclear[1] |

| Risk factors | Family history, obesity, type 2 diabetes, not enough exercise, erectile dysfunction[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and examination after ruling out other possible causes[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Heart failure, diabetes, prostate cancer[2] |

| Treatment | Lifestyle changes, medications, several procedures, surgery[1][2] |

| Medication | Alpha blockers such as terazosin, 5α-reductase inhibitors such as finasteride[1] |

| Frequency | 94 million men affected globally (2019)[3] |

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), also called prostate enlargement, is a noncancerous increase in size of the prostate gland.[1] Symptoms may include frequent urination, trouble starting to urinate, weak stream, inability to urinate, or loss of bladder control.[1] Complications can include urinary tract infections, bladder stones, and chronic kidney problems.[2]

The cause is unclear.[1] Risk factors include a family history, obesity, type 2 diabetes, not enough exercise, and erectile dysfunction.[1] Medications like pseudoephedrine, anticholinergics, and calcium channel blockers may worsen symptoms.[2] The underlying mechanism involves the prostate pressing on the urethra thereby making it difficult to pass urine out of the bladder.[1] Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms and examination after ruling out other possible causes.[2]

Treatment options include lifestyle changes, medications, a number of procedures, and surgery.[1][2] In those with mild symptoms, weight loss, decreasing caffeine intake, and exercise are recommended, although the quality of the evidence for exercise is low.[2][4] In those with more significant symptoms, medications may include alpha blockers such as terazosin or 5α-reductase inhibitors such as finasteride.[1] Surgical removal of part of the prostate may be carried out in those who do not improve with other measures.[2] Some herbal medicines that have been studied, such as saw palmetto, have not been shown to help.[2] Other herbal medicines somewhat effective at improving urine flow include beta-sitosterol[5] from Hypoxis rooperi (African star grass), pygeum (extracted from the bark of Prunus africana),[6] pumpkin seeds (Cucurbita pepo), and stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) root.[7]

As of 2019[update], about 94 million men aged 40 years and older are affected globally.[3] BPH typically begins after the age of 40.[1] The prevalence of clinically diagnosed BPH peaks at 24% in men aged 75–79 years.[3] Based on autopsy studies, half of males aged 50 and over are affected, and this figure climbs to 80% after the age of 80.[3] Although prostate specific antigen levels may be elevated in males with BPH, the condition does not increase the risk of prostate cancer.[8]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

BPH is the most common cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), which are divided into storage, voiding, and symptoms which occur after urination.[12] Storage symptoms include the need to urinate frequently, waking at night to urinate, urgency (compelling need to void that cannot be deferred), involuntary urination, including involuntary urination at night, or urge incontinence (urine leak following a strong sudden need to urinate).[13] Voiding symptoms include urinary hesitancy (a delay between trying to urinate and the flow actually beginning), intermittency (not continuous),[14] involuntary interruption of voiding, weak urinary stream, straining to void, a sensation of incomplete emptying, and uncontrollable leaking after the end of urination.[15][16][17] These symptoms may be accompanied by bladder pain or pain while urinating, called dysuria.[18]

Bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) can be caused by BPH.[19] Symptoms are abdominal pain, a continuous feeling of a full bladder, frequent urination, acute urinary retention (inability to urinate), pain during urination (dysuria), problems starting urination (urinary hesitancy), slow urine flow, starting and stopping (urinary intermittency), and nocturia.[20]

BPH can be a progressive disease, especially if left untreated. Incomplete voiding results in residual urine or urinary stasis, which can lead to an increased risk of urinary tract infection.[21]

Causes

[edit]Hormones

[edit]Most experts consider androgens (testosterone and related hormones) to play a permissive role in the development of BPH. This means that androgens must be present for BPH to occur, but do not necessarily directly cause the condition. This is supported by evidence suggesting that castrated boys do not develop BPH when they age. In a study of 26 eunuchs from the palace of the Qing dynasty still living in Beijing in 1960, the prostate could not be felt in 81% of the studied eunuchs.[22] The average time since castration was 54 years (range, 41–65 years). On the other hand, some studies suggest that administering exogenous testosterone is not associated with a significant increase in the risk of BPH symptoms, so the role of testosterone in prostate cancer and BPH is still unclear. Further randomized controlled trials with more participants are needed to quantify any risk of giving exogenous testosterone.[23]

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a metabolite of testosterone, is a critical mediator of prostatic growth. DHT is synthesized in the prostate from circulating testosterone by the action of the enzyme 5α-reductase, type 2. DHT can act in an autocrine fashion on the stromal cells or in paracrine fashion by diffusing into nearby epithelial cells. In both of these cell types, DHT binds to nuclear androgen receptors and signals the transcription of growth factors that are mitogenic to the epithelial and stromal cells. DHT is ten times more potent than testosterone because it dissociates from the androgen receptor more slowly. The importance of DHT in causing nodular hyperplasia is supported by clinical observations in which an inhibitor of 5α-reductase such as finasteride is given to men with this condition. Therapy with a 5α-reductase inhibitor markedly reduces the DHT content of the prostate and, in turn, reduces prostate volume and BPH symptoms.[24][25]

Testosterone promotes prostate cell proliferation,[26] but relatively low levels of serum testosterone are found in patients with BPH.[27][28] One small study has shown that medical castration lowers the serum and prostate hormone levels unevenly, having less effect on testosterone and dihydrotestosterone levels in the prostate.[29]

Besides testosterone and DHT, other androgens are also known to play a crucial role in BPH development. C

21 11-oxygenated steroids (pregnanes) have been identified are precursors to 11-oxygenated androgens which are also potent agonists for the androgen receptor.[30] Specifically, steroids like 11β-hydroxyprogesterone and 11-ketoprogesterone can be converted to 11-ketodihydrotestosterone, an 11-oxo form of DHT with the same potency. These precursors have also been detected in tissue biopsy samples from patients with BPH, as well as in their serum levels.[31][32][33] Besides that, androgens biosynthesized via a backdoor pathway can contribute to the development of BPH.[31]

While there is some evidence that estrogen may play a role in the cause of BPH, this effect appears to be mediated mainly through local conversion of androgens to estrogen in the prostate tissue rather than a direct effect of estrogen itself.[34] In canine in vivo studies castration, which significantly reduced androgen levels but left estrogen levels unchanged, caused significant atrophy of the prostate.[35] Studies looking for a correlation between prostatic hyperplasia and serum estrogen levels in humans have generally shown none.[28][36]

In 2008, Gat et al. published evidence that BPH is caused by failure in the spermatic venous drainage system resulting in increased hydrostatic pressure and local testosterone levels elevated more than 100-fold above serum levels.[37] If confirmed, this mechanism explains why serum androgen levels do not seem to correlate with BPH and why giving exogenous testosterone would not make much difference.

Diet

[edit]Studies indicate that dietary patterns may affect the development of BPH, but further research is needed to clarify any important relationship.[38] Studies from China suggest that greater protein intake may be a factor in the development of BPH. Men older than 60 in rural areas had very low rates of clinical BPH, while men living in cities and consuming more animal protein had a higher incidence.[39][40] On the other hand, a study in Japanese-American men in Hawaii found a strong negative association with alcohol intake, but a weak positive association with beef intake.[41] In a large prospective cohort study in the US (the Health Professionals Follow-up Study), investigators reported modest associations between BPH (men with strong symptoms of BPH or surgically confirmed BPH) and total energy and protein, but not fat intake.[42] There is also epidemiological evidence linking BPH with metabolic syndrome (concurrent obesity, impaired glucose metabolism and diabetes, high triglyceride levels, high levels of low-density cholesterol, and hypertension).[43]

Degeneration

[edit]Benign prostatic hyperplasia is an age-related disease. Misrepair-accumulation aging theory[44] suggests that the development of benign prostatic hyperplasia is a consequence of fibrosis and weakening of the muscular tissue in the prostate.[45] The muscular tissue is important in the functionality of the prostate, and provides the force for excreting the fluid produced by prostatic glands. However, repeated contractions and dilations of myofibers will unavoidably cause injuries and broken myofibers. Myofibers have a low potential for regeneration; therefore, collagen fibers need to be used to replace the broken myofibers. Such misrepairs make the muscular tissue weak in functioning, and the fluid secreted by glands cannot be excreted completely. Then, the accumulation of fluid in glands increases the resistance of muscular tissue during the movements of contractions and dilations, and more and more myofibers will be broken and replaced by collagen fibers.[46]

Pathophysiology

[edit]

As men age, the enzymes aromatase and 5-alpha reductase increase in activity. These enzymes are responsible for converting androgen hormones into estrogen and dihydrotestosterone, respectively. This metabolism of androgen hormones leads to a decrease in testosterone but increased levels of DHT and estrogen.

Both the glandular epithelial cells and the stromal cells (including muscular fibers) undergo hyperplasia in BPH.[2] Most sources agree that of the two tissues, stromal hyperplasia predominates, but the exact ratio of the two is unclear.[47]: 694

Anatomically the median and lateral lobes are usually enlarged, due to their highly glandular composition. The anterior lobe has little in the way of glandular tissue and is seldom enlarged. (Carcinoma of the prostate typically occurs in the posterior lobe – hence the ability to discern an irregular outline per rectal examination). The earliest microscopic signs of BPH usually begin between the age of 30 and 50 years old in the PUG, which is posterior to the proximal urethra.[47]: 694 In BPH, the majority of growth occurs in the transition zone (TZ) of the prostate.[47]: 694 In addition to these two classic areas, the peripheral zone (PZ) is also involved to a lesser extent.[47]: 695 Prostatic cancer typically occurs in the PZ. However, BPH nodules, usually from the TZ are often biopsied anyway to rule out cancer in the TZ.[47]: 695 BPH can be a progressive growth that in rare instances leads to exceptional enlargement.[48] In some males, the prostate enlargement exceeds 200 to 500 grams.[48] This condition has been defined as giant prostatic hyperplasia (GPH).[48]

Diagnosis

[edit]The clinical diagnosis of BPH is based on a history of LUTS (lower urinary tract symptoms), a digital rectal exam, and the exclusion of other causes of similar signs and symptoms. The degree of LUTS does not necessarily correspond to the size of the prostate. An enlarged prostate gland on rectal examination that is symmetric and smooth supports a diagnosis of BPH.[2] However, if the prostate gland feels asymmetrical, firm, or nodular, this raises concern for prostate cancer.[2]

Validated questionnaires such as the American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUA-SI), the International Prostate Symptom Score (I-PSS), and more recently the UWIN score (urgency, weak stream, incomplete emptying, and nocturia) are useful aids to making the diagnosis of BPH and quantifying the severity of symptoms.[2][49][50]

Laboratory investigations

[edit]Urinalysis is typically performed when LUTS are present and BPH is suspected to evaluate for signs of a urinary tract infection, glucose in the urine (suggestive of diabetes), or protein in the urine (suggestive of kidney disease).[2] Bloodwork including kidney function tests and prostate specific antigen (PSA) are often ordered to evaluate for kidney damage and prostate cancer, respectively.[2] However, checking blood PSA levels for prostate cancer screening is controversial and not necessarily indicated in every evaluation for BPH.[2] Benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer are both capable of increasing blood PSA levels and PSA elevation is unable to differentiate these two conditions well.[2] If PSA levels are checked and are high, then further investigation is warranted. Measures including PSA density, free PSA, rectal examination, and transrectal ultrasonography may help determine whether a PSA increase is due to BPH or prostate cancer.[2]

Imaging and other investigations

[edit]Uroflowmetry is done to measure the rate of urine flow and total volume of urine voided when the subject is urinating.[51]

Abdominal ultrasound examination of the prostate and kidneys is often performed to rule out hydronephrosis and hydroureter. Incidentally, cysts, tumours, and stones may be found on ultrasound. Post-void residual volume of more than 100 ml may indicate significant obstruction.[52] Prostate size of 30 cc or more indicates enlargement of the prostate.[53]

Prostatic calcification can be detected through transrectal ultrasound (TRUS). Calcification is due to solidification of prostatic secretions or calcified corpora amylacea (hyaline masses on the prostate gland). Calcification is also found in a variety of other conditions such as prostatitis, chronic pelvic pain syndrome, and prostate cancer.[54][55] For those with elevated levels of PSA, TRUS guided biopsy is performed to take a sample of the prostate for investigation.[56] Although MRI is more accurate than TRUS in determining prostate volume, TRUS is less expensive and almost as accurate as MRI. Therefore, TRUS is still preferred to measure prostate volume.[57]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]Medical conditions

[edit]The differential diagnosis for LUTS is broad and includes various medical conditions, neurologic disorders, and other diseases of the bladder, urethra, and prostate such as bladder cancer, urinary tract infection, urethral stricture, urethral calculi (stones), chronic prostatitis, and prostate cancer.[2] Neurogenic bladder can cause urinary retention and cause symptoms similar to those of BPH. This may occur as a result of uncoordinated contraction of the bladder muscle or impairment in the timing of bladder muscle contraction and urethral sphincter relaxation.[2] Notable causes of neurogenic bladder include disorders of the central nervous system such as Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, and spinal cord injuries as well as disorders of the peripheral nervous system such as diabetes mellitus, vitamin B12 deficiency, and alcohol-induced nerve damage.[2] Individuals affected by heart failure often experience nighttime awakenings to urinate due to redistribution of fluid accumulated in swollen legs.[2]

Medications

[edit]Certain medications can increase urination difficulties by increasing bladder outlet resistance due to increased smooth muscle tone at the prostate or bladder neck and contribute to LUTS.[2] Alpha-adrenergic agonist medications, such as decongestants with pseudoephedrine can increase bladder outlet resistance.[2] In contrast, calcium channel blockers and anticholinergic medications can worsen urinary retention by promoting bladder muscle relaxation.[2] Diuretic medications such as loop diuretics (e.g., furosemide) or thiazides (e.g., chlorthalidone) can cause or worsen urinary frequency and nighttime awakenings to urinate.[2]

-

Micrograph showing nodular hyperplasia (left off center) of the prostate from a transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). H&E stain.

-

Microscopic examination of different types of prostate tissues (stained with immunohistochemical techniques): A. Normal (non-neoplastic) prostatic tissue (NNT). B. Benign prostatic hyperplasia. C. High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. D. Prostatic adenocarcinoma (PCA).

Management

[edit]When treating and managing benign prostatic hyperplasia, the aim is to prevent complications related to the disease and improve or relieve symptoms.[58] Approaches used include lifestyle modifications, medications, catheterization, and surgery.

Lifestyle

[edit]

Lifestyle alterations to address the symptoms of BPH include physical activity,[59] decreasing fluid intake before bedtime, moderating the consumption of alcohol and caffeine-containing products, and following a timed voiding schedule.

Patients can also attempt to avoid products and medications with anticholinergic properties that may exacerbate urinary retention symptoms of BPH, including antihistamines, decongestants, opioids, and tricyclic antidepressants; however, changes in medications should be done with input from a medical professional.[60]

Physical activity

[edit]Physical activity has been recommended as a treatment for urinary tract symptoms. A 2019 Cochrane review of six studies involving 652 men assessing the effects of physical activity alone, and physical activity as a part of a self-management program, among others. However, the quality of evidence was very low and therefore it remains uncertain whether physical activity is helpful in men experiencing urinary symptoms caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia.[61]

Voiding position

[edit]Voiding position when urinating may influence urodynamic parameters (urinary flow rate, voiding time, and post-void residual volume).[62] A meta-analysis found no differences between the standing and sitting positions for healthy males, but that, for elderly males with lower urinary tract symptoms, voiding in the sitting position-- [63]

- decreased the post-void residual volume;

- increased the maximum urinary flow, comparable with pharmacological intervention; and

- decreased the voiding time.

This urodynamic profile is associated with a lower risk of urologic complications, such as cystitis and bladder stones.

Medications

[edit]The two main medication classes for BPH management are alpha blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors.[64]

Alpha-blockers

[edit]Selective α1-blockers are the most common choice for initial therapy.[65][66][67] They include alfuzosin,[68][69] doxazosin,[70] silodosin, tamsulosin, terazosin, and naftopidil.[58] They have a small to moderate benefit at improving symptoms.[71][58][72] Selective alpha-1 blockers are similar in effectiveness but have slightly different side effect profiles.[71][58][72] Alpha blockers relax smooth muscle in the prostate and the bladder neck, thus decreasing the blockage of urine flow. Common side effects of alpha-blockers include orthostatic hypotension (a head rush or dizzy spell when standing up or stretching), ejaculation changes, erectile dysfunction,[73] headaches, nasal congestion, and weakness. For men with LUTS due to an enlarged prostate, the effects of naftopidil, tamsulosin, and silodosin on urinary symptoms and quality of life may be similar.[58] Naftopidil and tamsulosin may have similar levels of unwanted sexual side effects but fewer unwanted side effects than silodosin.[58]

Tamsulosin and silodosin are selective α1 receptor blockers that preferentially bind to the α1A receptor in the prostate instead of the α1B receptor in the blood vessels. Less-selective α1 receptor blockers such as terazosin and doxazosin may lower blood pressure. The older, less selective α1-adrenergic blocker prazosin is not a first-line choice for either high blood pressure or prostatic hyperplasia; it is a choice for patients who present with both problems at the same time. The older, broadly non-selective alpha-blocker medications such as phenoxybenzamine are not recommended for control of BPH.[74] Non-selective alpha-blockers such as terazosin and doxazosin may also require slow dose adjustments as they can lower blood pressure and cause syncope (fainting) if the response to the medication is too strong.

5α-reductase inhibitors

[edit]The 5α-reductase inhibitors finasteride and dutasteride may also be used in people with BPH.[75] These medications inhibit the 5α-reductase enzyme, which, in turn, inhibits the production of DHT, a hormone responsible for enlarging the prostate. Effects may take longer to appear than alpha blockers, but they persist for many years.[76] When used together with alpha-blockers, no benefit was reported in short-term trials, but in a longer-term study (3–4 years) there was a greater reduction in BPH progression to acute urinary retention and surgery than with either agent alone, especially in people with more severe symptoms and larger prostates.[77][78][79] Other trials have confirmed reductions in symptoms, within 6 months in one trial, an effect that was maintained after withdrawal of the alpha blocker.[78][80] Side effects include decreased libido and ejaculatory or erectile dysfunction.[81][82] The 5α-reductase inhibitors are contraindicated in pregnant women because of their teratogenicity due to interference with fetal testosterone metabolism, and as a precaution, pregnant women should not handle crushed or broken tablets.[83]

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors (PDE)

[edit]A 2018 Cochrane review of studies on men over 60 with moderate to severe lower urinary tract symptoms analyzed the impacts of phosphodiesterase inhibitors (PDE) in comparison to other drugs.[90] These drugs may improve urinary symptoms slightly and reduce urinary bother but may also cause more side effects than placebo. The evidence in this review found that there is probably no difference between PDE and alpha blockers, however when used in combination they may provide a greater improvement in symptoms (with more side effects). PDE also likely improves symptoms when used with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors.

Several phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors are also effective but may require multiple doses daily to maintain adequate urine flow.[91][92] Tadalafil, a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, was considered then rejected by NICE in the UK for the treatment of symptoms associated with BPH.[93] In 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved tadalafil to treat the signs and symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia, and for the treatment of BPH and erectile dysfunction (ED), when the conditions occur simultaneously.[94]

Others

[edit]Antimuscarinics such as tolterodine may also be used, especially in combination with alpha-blockers.[95] They act by decreasing acetylcholine effects on the smooth muscle of the bladder, thus helping control symptoms of an overactive bladder.[96]

Self-catheterization

[edit]Intermittent urinary catheterization is used to relieve the bladder in people with urinary retention. Self-catheterization is an option in BPH when it is difficult or impossible to empty the bladder.[97] Urinary tract infection is the most common complication of intermittent catheterization.[98] Several techniques and types of catheter are available, including sterile (single-use) and clean (multiple use) catheters, but, based on current information, none is superior to others in reducing the incidence of urinary tract infection.[99]

Surgery

[edit]

If medical treatment is not effective, surgery may be performed. Surgical techniques used include the following:

- Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP): the gold standard.[100] TURP is thought to be the most effective approach for improving urinary symptoms and urinary flow, however, this surgical procedure may be associated with complications in up to 20% of men.[100] Surgery carries some risk of complications, such as retrograde ejaculation (most commonly), erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, urethral strictures.[101]

- Transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP): rarely performed; the technique is similar to TURP but less definitive.

- Open prostatectomy: not usually performed nowadays due to its high morbidity, even if the results are excellent.

Other less invasive surgical approaches (requiring spinal anesthesia) include:

- Holmium laser ablation of the prostate (HoLAP)

- Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLeP)

- Thulium laser transurethral vaporesection of the prostate (ThuVARP)

- Photoselective vaporization of the prostate (PVP)

- Aquablation therapy: a type of surgery using a water jet to remove prostatic tissue.

Minimally invasive procedures

[edit]Some less invasive procedures are available according to patients' preferences and co-morbidities. These are performed as outpatient procedures with local anesthesia.

- Prostatic artery embolization: an endovascular procedure performed in interventional radiology.[102] Through catheters, embolic agents are released in the main branches of the prostatic artery, in order to induce a decrease in the size of the prostate gland, thus reducing the urinary symptoms.[103]

- Water vapor thermal therapy (marketed as Rezum): This is a newer office procedure for removing prostate tissue using steam aimed at preserving sexual function.

- Prostatic urethral lift (marketed as UroLift): This intervention consists of a system of a device and an implant designed to pull the prostatic lobe away from the urethra.[104]

- Transurethral microwave thermotherapy (TUMT) is an outpatient procedure that is less invasive compared to surgery and involves using microwaves (heat) to shrink prostate tissue that is enlarged.[100]

- Temporary implantable nitinol device (TIND and iTIND): is a device that is placed in the urethra that, when released, is expanded, reshaping the urethra and the bladder neck.[105]

Alternative medicine

[edit]While herbal remedies are commonly used, a 2016 review found the herbs studied to be no better than placebos.[164] Particularly, several reviews found that saw palmetto extract, while one of the most commonly used, is no better than a placebo both in symptom relief and in decreasing prostate size.[165][166][167]

Epidemiology

[edit]

Globally, benign prostatic hyperplasia affects about 94 million males as of 2019[update].[3]

The prostate gets larger in most men as they get older. For a symptom-free man of 46 years, the risk of developing BPH over the next 30 years is 45%. Incidence rates increase from 3 cases per 1000 man-years at age 45–49 years, to 38 cases per 1000 man-years by the age of 75–79 years. While the prevalence rate is 2.7% for men aged 45–49, it increases to 24% by the age of 80 years.[169]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Prostate Enlargement (Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia)". NIDDK. September 2014. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Kim EH, Larson JA, Andriole GL (2016). "Management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia". Annual Review of Medicine (Review). 67: 137–151. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-063014-123902. PMID 26331999.

- ^ a b c d e Awedew AF, Han H, Abbasi B, Abbasi-Kangevari M, Ahmed MB, Almidani O, et al. (GBD 2019 Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Collaborators) (November 2022). "The global, regional, and national burden of benign prostatic hyperplasia in 204 countries and territories from 2000 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019". The Lancet. Healthy Longevity. 3 (11): e754 – e776. doi:10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00213-6. PMC 9640930. PMID 36273485.

- ^ Silva V, Grande AJ, Peccin MS (April 2019). "Physical activity for lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic obstruction". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (4): CD012044. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012044.pub2. PMC 6450803. PMID 30953341.

- ^ Wilt T, Ishani A, MacDonald R, Stark G, Mulrow C, Lau J (1999). Wilt TJ (ed.). "Beta-sitosterols for benign prostatic hyperplasia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1999 (2): CD001043. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001043. PMC 8407049. PMID 10796740.

- ^ Wilt T, Ishani A, Mac Donald R, Rutks I, Stark G (1998). Wilt TJ (ed.). "Pygeum africanum for benign prostatic hyperplasia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1998 (1): CD001044. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001044. PMC 7032619. PMID 11869585.

- ^ Wilt TJ, Ishani A, Rutks I, MacDonald R (December 2000). "Phytotherapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia". Public Health Nutrition. 3 (4A): 459–472. doi:10.1017/S1368980000000549. PMID 11276294.

- ^ Chang RT, Kirby R, Challacombe BJ (April 2012). "Is there a link between BPH and prostate cancer?". The Practitioner. 256 (1750): 13–6, 2. PMID 22792684.

- ^ Berry SJ, Coffey DS, Walsh PC, Ewing LL (September 1984). "The development of human benign prostatic hyperplasia with age". The Journal of Urology. 132 (3): 474–479. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)49698-4. PMID 6206240.

- ^ Chute CG, Panser LA, Girman CJ, Oesterling JE, Guess HA, Jacobsen SJ, et al. (July 1993). "The prevalence of prostatism: a population-based survey of urinary symptoms". The Journal of Urology. 150 (1): 85–89. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)35405-8. PMID 7685427.

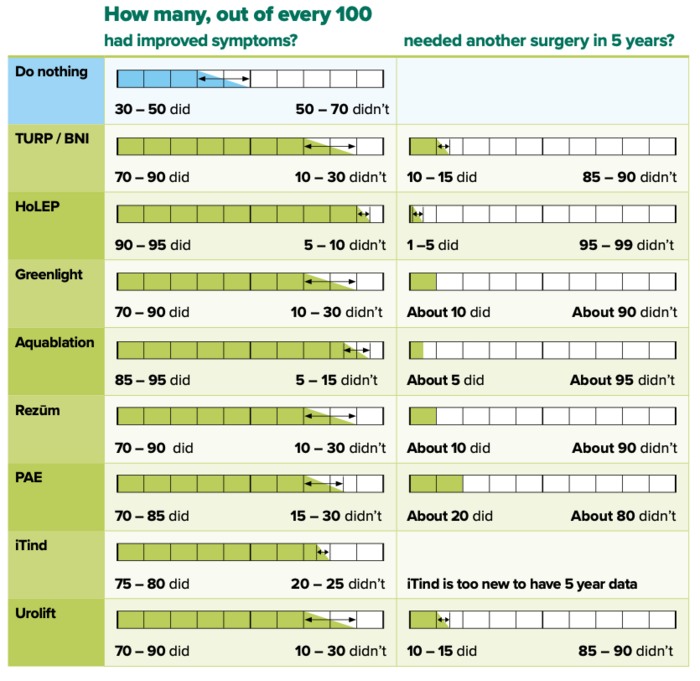

- ^ a b c d e f g "NHS England » Decision support tool: making a decision about enlarged prostate (BPE)". www.england.nhs.uk. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Lower urinary tract symptoms in men: management, NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence)

- ^ "Urge incontinence". MedlinePlus. US National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ White JR, O'Brien III DP, Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW (1990). "Incontinence and Stream Abnormalities". Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations (3rd ed.). Boston: Butterworths. ISBN 9780409900774. PMID 21250138.

- ^ Robinson J (11 February 2008). "Post-micturition dribble in men: causes and treatment". Nursing Standard. 22 (30): 43–46. doi:10.7748/ns2008.04.22.30.43.c6440. PMID 18459613.

- ^ Sarma AV, Wei JT (July 2012). "Clinical practice. Benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms". The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (3): 248–257. doi:10.1056/nejmcp1106637. PMID 22808960.

- ^ "Urination – difficulty with flow". MedlinePlus. US National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ "Urination – painful". MedlinePlus. US National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ "Bladder outlet obstruction". MedlinePlus. US National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ^ "Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Truzzi JC, Almeida FM, Nunes EC, Sadi MV (July 2008). "Residual urinary volume and urinary tract infection--when are they linked?". The Journal of Urology. 180 (1): 182–185. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.044. PMID 18499191.

- ^ Wu CP, Gu FL (1991). "The prostate in eunuchs". Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 370: 249–255. PMID 1924456.

- ^ "Testosterone and Aging: Clinical Research Directions". NCBI Bookshelf. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "Proscar (finasteride) Prescribing Information" (PDF). FDA – Drug Documents. Merck and Company. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ Bartsch G, Rittmaster RS, Klocker H (April 2002). "Dihydrotestosterone and the concept of 5alpha-reductase inhibition in human benign prostatic hyperplasia". World Journal of Urology. 19 (6): 413–425. doi:10.1007/s00345-002-0248-5. PMID 12022710. S2CID 3257666.

- ^ Feldman BJ, Feldman D (October 2001). "The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 1 (1): 34–45. doi:10.1038/35094009. PMID 11900250. S2CID 205020623.

- ^ Lagiou P, Mantzoros CS, Tzonou A, Signorello LB, Lipworth L, Trichopoulos D (1997). "Serum steroids in relation to benign prostatic hyperplasia". Oncology. 54 (6): 497–501. doi:10.1159/000227609. PMID 9394847.

- ^ a b Roberts RO, Jacobson DJ, Rhodes T, Klee GG, Leiber MM, Jacobsen SJ (October 2004). "Serum sex hormones and measures of benign prostatic hyperplasia". The Prostate. 61 (2): 124–131. doi:10.1002/pros.20080. PMID 15305335. S2CID 24288565.

- ^ Page ST, Lin DW, Mostaghel EA, Hess DL, True LD, Amory JK, et al. (October 2006). "Persistent intraprostatic androgen concentrations after medical castration in healthy men". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 91 (10): 3850–3856. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-0968. PMID 16882745.

- ^ Dimitrakov J, Joffe HV, Soldin SJ, Bolus R, Buffington CA, Nickel JC (February 2008). "Adrenocortical hormone abnormalities in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". Urology. 71 (2): 261–266. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.09.025. PMC 2390769. PMID 18308097.

- ^ a b du Toit T, Swart AC (February 2020). "The 11β-hydroxyandrostenedione pathway and C11-oxy C21 backdoor pathway are active in benign prostatic hyperplasia yielding 11keto-testosterone and 11keto-progesterone". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 196: 105497. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.105497. PMID 31626910. S2CID 204734045.

- ^ Masiutin MG, Yadav MK (November 2022). ""Re: Adrenocortical Hormone Abnormalities in Men With Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome"". Urology. 169: 273. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2022.07.051. PMID 35987379. S2CID 251657694.

- ^ Dimitrakoff J, Nickel JC (November 2022). "Author Reply". Urology. 169: 273–274. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2022.07.049. PMID 35985522. S2CID 251658492.

- ^ Ho CK, Nanda J, Chapman KE, Habib FK (June 2008). "Oestrogen and benign prostatic hyperplasia: effects on stromal cell proliferation and local formation from androgen". The Journal of Endocrinology. 197 (3): 483–491. doi:10.1677/JOE-07-0470. PMID 18492814.

- ^ Niu YJ, Ma TX, Zhang J, Xu Y, Han RF, Sun G (March 2003). "Androgen and prostatic stroma". Asian Journal of Andrology. 5 (1): 19–26. PMID 12646998.

- ^ Ansari MA, Begum D, Islam F (2008). "Serum sex steroids, gonadotrophins and sex hormone-binding globulin in prostatic hyperplasia". Annals of Saudi Medicine. 28 (3): 174–178. doi:10.4103/0256-4947.51727. PMC 6074428. PMID 18500180.

- ^ Gat Y, Gornish M, Heiblum M, Joshua S (October 2008). "Reversal of benign prostate hyperplasia by selective occlusion of impaired venous drainage in the male reproductive system: novel mechanism, new treatment". Andrologia. 40 (5): 273–281. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0272.2008.00883.x. PMID 18811916. S2CID 205442245.

- ^ Heber D (April 2002). "Prostate enlargement: the canary in the coal mine?". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 75 (4): 605–606. doi:10.1093/ajcn/75.4.605. PMID 11916745.

- ^ Zhang SX, Yu B, Guo SL, Wang YW, Yin CK (February 2003). "[Comparison of incidence of BPH and related factors between urban and rural inhabitants in district of Wannan]". Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue = National Journal of Andrology. 9 (1): 45–47. PMID 12680332.

- ^ Gu F (March 1997). "Changes in the prevalence of benign prostatic hyperplasia in China". Chinese Medical Journal. 110 (3): 163–166. PMID 9594331.

- ^ Chyou PH, Nomura AM, Stemmermann GN, Hankin JH (1993). "A prospective study of alcohol, diet, and other lifestyle factors in relation to obstructive uropathy". The Prostate. 22 (3): 253–264. doi:10.1002/pros.2990220308. PMID 7683816. S2CID 32639108.

- ^ Suzuki S, Platz EA, Kawachi I, Willett WC, Giovannucci E (April 2002). "Intakes of energy and macronutrients and the risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 75 (4): 689–697. doi:10.1093/ajcn/75.4.689. PMID 11916755.

- ^ Gacci M, Corona G, Vignozzi L, Salvi M, Serni S, De Nunzio C, et al. (January 2015). "Metabolic syndrome and benign prostatic enlargement: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BJU International. 115 (1): 24–31. doi:10.1111/bju.12728. hdl:2158/953282. PMID 24602293. S2CID 22937831.

- ^ Wang J, Michelitsch T, Wunderlin A, Mahadeva R (March 2009). "Aging as a consequence of misrepair--A novel theory of aging". Nature Precedings. arXiv:0904.0575. doi:10.1038/npre.2009.2988.1.

- ^ Wang-Michelitsch J, Michelitsch T (2015). "Tissue fibrosis: a principal evidence for the central role of Misrepairs in aging". arXiv:1503.01376 [cs.DM].

- ^ Roehrborn CG (2005). "Benign prostatic hyperplasia: an overview". Reviews in Urology. 7 (Suppl 9): S3 – S14. PMC 1477638. PMID 16985902.

- ^ a b c d e Wasserman NF (September 2006). "Benign prostatic hyperplasia: a review and ultrasound classification". Radiologic Clinics of North America. 44 (5): 689–710, viii. doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2006.07.005. PMID 17030221.

- ^ a b c Ojewola RW, Tijani KH, Fatuga AL, Onyeze CI, Okeke CJ (2020). "Management of a giant prostatic enlargement: Case report and review of the literature". The Nigerian Postgraduate Medical Journal. 27 (3). Medknow: 242–247. doi:10.4103/npmj.npmj_69_20. PMID 32687126. S2CID 220652018.

- ^ Parsons JK (December 2010). "Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia and Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: Epidemiology and Risk Factors". Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports. 5 (4): 212–218. doi:10.1007/s11884-010-0067-2. PMC 3061630. PMID 21475707.

- ^ Eid K, Krughoff K, Stoimenova D, Smith D, Phillips J, O'Donnell C, et al. (January 2014). "Validation of the Urgency, Weak stream, Incomplete emptying, and Nocturia (UWIN) score compared with the American Urological Association Symptoms Score in assessing lower urinary tract symptoms in the clinical setting". Urology. 83 (1): 181–185. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2013.08.039. PMID 24139351.

- ^ Gammie A, Drake MJ (August 2018). "The fundamentals of uroflowmetry practice, based on International Continence Society good urodynamic practices recommendations". Neurourology and Urodynamics. 37 (S6): S44 – S49. doi:10.1002/nau.23777. PMID 30614059. S2CID 58586667.

- ^ Foo KT (June 2013). "The Role of Transabdominal Ultrasound in Office Urology". Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare. 22 (2): 125–130. doi:10.1177/201010581302200208. ISSN 2010-1058. S2CID 74205747.

- ^ Aprikian S, Luz M, Brimo F, Scarlata E, Hamel L, Cury FL, et al. (July 2019). "Improving ultrasound-based prostate volume estimation". BMC Urology. 19 (1): 68. doi:10.1186/s12894-019-0492-2. PMC 6657110. PMID 31340802.

- ^ Kitzing YX, Prando A, Varol C, Karczmar GS, Maclean F, Oto A (January 2016). "Benign Conditions That Mimic Prostate Carcinoma: MR Imaging Features with Histopathologic Correlation". Radiographics. 36 (1): 162–175. doi:10.1148/rg.2016150030. PMC 5496681. PMID 26587887.

- ^ Singh S, Martin E, Tregidgo HF, Treeby B, Bandula S (October 2021). "Prostatic calcifications: Quantifying occurrence, radiodensity, and spatial distribution in prostate cancer patients". Urologic Oncology. 39 (10): 728.e1–728.e6. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.12.028. PMC 8492071. PMID 33485763.

- ^ Mitterberger M, Horninger W, Aigner F, Pinggera GM, Steppan I, Rehder P, et al. (March 2010). "Ultrasound of the prostate". Cancer Imaging. 10 (1): 40–48. doi:10.1102/1470-7330.2010.0004. PMC 2842183. PMID 20199941.

- ^ Lee JS, Chung BH (2007). "Transrectal ultrasound versus magnetic resonance imaging in the estimation of prostate volume as compared with radical prostatectomy specimens". Urologia Internationalis. 78 (4): 323–327. doi:10.1159/000100836. PMID 17495490. S2CID 10731245.

- ^ a b c d e f Hwang EC, Gandhi S, Jung JH, Imamura M, Kim MH, Pang R, et al. (October 2018). "Naftopidil for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms compatible with benign prostatic hyperplasia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (10): CD007360. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007360.pub3. PMC 6516835. PMID 30306544.

- ^ Silva V, Grande AJ, Peccin MS (April 2019). "Physical activity for lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic obstruction". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (4): CD012044. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012044.pub2. PMC 6450803. PMID 30953341.

- ^ "Benign prostatic hyperplasia". University of Maryland Medical Center. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017.

- ^ Silva V, Grande AJ, Peccin MS, et al. (Cochrane Urology Group) (April 2019). "Physical activity for lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic obstruction". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (4): CD012044. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012044.pub2. PMC 6450803. PMID 30953341.

- ^ De Jong Y, Pinckaers JH, Ten Brinck RM, Lycklama à Nijeholt AA. "Influence of voiding posture on urodynamic parameters in men: a literature review" (PDF). Nederlands Tijdschrift voor urologie. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ de Jong Y, Pinckaers JH, ten Brinck RM, Lycklama à Nijeholt AA, Dekkers OM (2014). "Urinating standing versus sitting: position is of influence in men with prostate enlargement. A systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS ONE. 9 (7): e101320. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j1320D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101320. PMC 4106761. PMID 25051345.

- ^ Silva J, Silva CM, Cruz F (January 2014). "Current medical treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms/BPH: do we have a standard?". Current Opinion in Urology. 24 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1097/mou.0000000000000007. PMID 24231531. S2CID 40954757.

- ^ Roehrborn CG, Nuckolls JG, Wei JT, Steers W, et al. (BPH Registry and Patient Survey Steering Committee) (October 2007). "The benign prostatic hyperplasia registry and patient survey: study design, methods, and patient baseline characteristics". BJU International. 100 (4): 813–819. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07061.x. hdl:2027.42/73286. PMID 17822462. S2CID 21001077.

- ^ Black L, Naslund MJ, Gilbert TD, Davis EA, Ollendorf DA (March 2006). "An examination of treatment patterns and costs of care among patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia". The American Journal of Managed Care. 12 (4 Suppl): S99 – S110. PMID 16551208.

- ^ Hutchison A, Farmer R, Verhamme K, Berges R, Navarrete RV (January 2007). "The efficacy of drugs for the treatment of LUTS/BPH, a study in 6 European countries". European Urology. 51 (1): 207–15, discussion 215–6. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2006.06.012. PMID 16846678.

- ^ MacDonald R, Wilt TJ (October 2005). "Alfuzosin for treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms compatible with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review of efficacy and adverse effects". Urology. 66 (4): 780–788. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2005.05.001. PMID 16230138.

- ^ Roehrborn CG (December 2001). "Efficacy and safety of once-daily alfuzosin in the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms and clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial". Urology. 58 (6): 953–959. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(01)01448-0. PMID 11744466.

- ^ MacDonald R, Wilt TJ, Howe RW (December 2004). "Doxazosin for treating lower urinary tract symptoms compatible with benign prostatic obstruction: a systematic review of efficacy and adverse effects". BJU International. 94 (9): 1263–1270. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05154.x. PMID 15610102. S2CID 6640867.

- ^ a b Wilt TJ, Mac Donald R, Rutks I (2003). Wilt T (ed.). "Tamsulosin for benign prostatic hyperplasia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD002081. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002081. PMID 12535426.

- ^ a b Djavan B, Marberger M (1999). "A meta-analysis on the efficacy and tolerability of alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonists in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic obstruction". European Urology. 36 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1159/000019919. PMID 10364649. S2CID 73366414.

- ^ Santillo VM, Lowe FC (2006). "Treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia in patients with cardiovascular disease". Drugs & Aging. 23 (10): 795–805. doi:10.2165/00002512-200623100-00003. PMID 17067183. S2CID 24428368.

- ^ AUA Practice Guidelines Committee (August 2003). "AUA guideline on management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (2003). Chapter 1: Diagnosis and treatment recommendations". The Journal of Urology. 170 (2 Pt 1): 530–547. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000078083.38675.79. PMID 12853821.

- ^ Blankstein U, Van Asseldonk B, Elterman DS (February 2016). "BPH update: medical versus interventional management" (PDF). The Canadian Journal of Urology. 23 (Suppl 1): 10–15. PMID 26924590. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2016.

- ^ Roehrborn CG, Bruskewitz R, Nickel JC, McConnell JD, Saltzman B, Gittelman MC, et al. (Proscar Long-Term Efficacy Safety Study Group) (March 2004). "Sustained decrease in incidence of acute urinary retention and surgery with finasteride for 6 years in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia". The Journal of Urology. 171 (3): 1194–1198. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000112918.74410.94. PMID 14767299.

- ^ Roehrborn CG, Barkin J, Tubaro A, Emberton M, Wilson TH, Brotherton BJ, et al. (April 2014). "Influence of baseline variables on changes in International Prostate Symptom Score after combined therapy with dutasteride plus tamsulosin or either monotherapy in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms: 4-year results of the CombAT study". BJU International. 113 (4): 623–635. doi:10.1111/bju.12500. PMID 24127818. S2CID 38243275.

- ^ a b Greco KA, McVary KT (December 2008). "The role of combination medical therapy in benign prostatic hyperplasia". International Journal of Impotence Research. 20 (Suppl 3): S33 – S43. doi:10.1038/ijir.2008.51. PMID 19002123.

- ^ Kaplan SA, McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, Meehan AG, Lee MW, Noble WR, et al. (Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS) Research Group) (January 2006). "Combination therapy with doxazosin and finasteride for benign prostatic hyperplasia in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms and a baseline total prostate volume of 25 ml or greater". The Journal of Urology. 175 (1): 217–20, discussion 220–1. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00041-8. PMID 16406915.

- ^ Barkin J, Guimarães M, Jacobi G, Pushkar D, Taylor S, van Vierssen Trip OB (October 2003). "Alpha-blocker therapy can be withdrawn in the majority of men following initial combination therapy with the dual 5alpha-reductase inhibitor dutasteride". European Urology. 44 (4): 461–466. doi:10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00367-1. PMID 14499682.

- ^ Gormley GJ, Stoner E, Bruskewitz RC, Imperato-McGinley J, Walsh PC, McConnell JD, et al. (October 1992). "The effect of finasteride in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Finasteride Study Group". The New England Journal of Medicine. 327 (17): 1185–1191. doi:10.1056/NEJM199210223271701. PMID 1383816.

- ^ Gacci M, Ficarra V, Sebastianelli A, Corona G, Serni S, Shariat SF, et al. (June 2014). "Impact of medical treatments for male lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia on ejaculatory function: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 11 (6): 1554–1566. doi:10.1111/jsm.12525. PMID 24708055.

- ^ Deters L. "Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy Treatment & Management". Medscape. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ a b McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, Bautista OM, Andriole GL, Dixon CM, Kusek JW, et al. (December 2003). "The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (25): 2387–2398. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa030656. PMID 14681504.

- ^ a b Roehrborn CG, Siami P, Barkin J, Damião R, Major-Walker K, Nandy I, et al. (January 2010). "The effects of combination therapy with dutasteride and tamsulosin on clinical outcomes in men with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: 4-year results from the CombAT study". European Urology. 57 (1): 123–131. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2009.09.035. PMID 19825505.

- ^ a b Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Rovner ES, Carlsson M, Bavendam T, Guan Z (November 2006). "Tolterodine and tamsulosin for treatment of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and overactive bladder: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 296 (19): 2319–2328. doi:10.1001/jama.296.19.2319. PMID 17105794.

- ^ van Dijk MM, de la Rosette JJ, Michel MC (1 February 2006). "Effects of alpha(1)-adrenoceptor antagonists on male sexual function". Drugs. 66 (3): 287–301. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666030-00002. PMID 16526818.

- ^ Descazeaud A, de La Taille A, Giuliano F, Desgrandchamps F, Doridot G (March 2015). "[Negative effects on sexual function of medications for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms related to benign prostatic hyperplasia]". Progres en Urologie. 25 (3): 115–127. doi:10.1016/j.purol.2014.12.003. PMID 25605342.

- ^ "Evidence | Lower urinary tract symptoms in men: management | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. 23 May 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Pattanaik S, Mavuduru RS, Panda A, Mathew JL, Agarwal MM, Hwang EC, et al. (Cochrane Urology Group) (November 2018). "Phosphodiesterase inhibitors for lower urinary tract symptoms consistent with benign prostatic hyperplasia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (11): CD010060. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010060.pub2. PMC 6517182. PMID 30480763.

- ^ Wang Y, Bao Y, Liu J, Duan L, Cui Y (January 2018). "Tadalafil 5 mg Once Daily Improves Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Erectile Dysfunction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. 10 (1): 84–92. doi:10.1111/luts.12144. PMID 29341503. S2CID 23929021.

- ^ Pattanaik S, Mavuduru RS, Panda A, Mathew JL, Agarwal MM, Hwang EC, et al. (November 2018). "Phosphodiesterase inhibitors for lower urinary tract symptoms consistent with benign prostatic hyperplasia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (11): CD010060. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010060.pub2. PMC 6517182. PMID 30480763.

- ^ "Hyperplasia (benign prostatic) – tadalafil (terminated appraisal) (TA273)". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). 23 January 2013. Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "FDA approves Cialis to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Rovner ES, Carlsson M, Bavendam T, Guan Z (November 2006). "Tolterodine and tamsulosin for treatment of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and overactive bladder: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 296 (19): 2319–2328. doi:10.1001/jama.296.19.2319. PMID 17105794.

- ^ Abrams P, Andersson KE (November 2007). "Muscarinic receptor antagonists for overactive bladder". BJU International. 100 (5): 987–1006. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.2007.07205.x. PMID 17922784. S2CID 30983780.

- ^ "Prostate enlargement (benign prostatic hyperplasia)". Harvard Health Content. Harvard Health Publications. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ Wyndaele JJ (October 2002). "Complications of intermittent catheterization: their prevention and treatment". Spinal Cord. 40 (10): 536–541. doi:10.1038/sj.sc.3101348. PMID 12235537.

- ^ Prieto JA, Murphy CL, Stewart F, Fader M (October 2021). "Intermittent catheter techniques, strategies and designs for managing long-term bladder conditions". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD006008. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006008.pub5. PMC 8547544. PMID 34699062.

- ^ a b c Franco JV, Garegnani L, Escobar Liquitay CM, Borofsky M, Dahm P (June 2021). "Transurethral microwave thermotherapy for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (6): CD004135. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004135.pub4. PMC 8236484. PMID 34180047.

- ^ "Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) - Risks". nhs.uk. 24 October 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Kuang M, Vu A, Athreya S (May 2017). "A Systematic Review of Prostatic Artery Embolization in the Treatment of Symptomatic Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia". CardioVascular and Interventional Radiology. 40 (5): 655–663. doi:10.1007/s00270-016-1539-3. PMID 28032133. S2CID 12154537.

- ^ Pisco J, Bilhim T, Pinheiro LC, Fernandes L, Pereira J, Costa NV, et al. (May 2016). "Prostate Embolization as an Alternative to Open Surgery in Patients with Large Prostate and Moderate to Severe Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms". Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 27 (5): 700–708. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2016.01.138. PMID 27019980.

- ^ McNicholas TA (May 2016). "Benign prostatic hyperplasia and new treatment options - a critical appraisal of the UroLift system". Medical Devices: Evidence and Research. 9: 115–123. doi:10.2147/MDER.S60780. PMC 4876946. PMID 27274321.

- ^ Porpiglia F, Fiori C, Bertolo R, Garrou D, Cattaneo G, Amparore D (August 2015). "Temporary implantable nitinol device (TIND): a novel, minimally invasive treatment for relief of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) related to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): feasibility, safety and functional results at 1 year of follow-up". BJU International. 116 (2): 278–287. doi:10.1111/bju.12982. hdl:2318/1623503. PMID 25382816. S2CID 5712711.

- ^ Gratzke C, Barber N, Speakman MJ, Berges R, Wetterauer U, Greene D, et al. (May 2017). "Prostatic urethral lift vs transurethral resection of the prostate: 2-year results of the BPH6 prospective, multicentre, randomized study". BJU International. 119 (5): 767–775. doi:10.1111/bju.13714. PMID 27862831.

- ^ Chughtai B, Elterman D, Shore N, Gittleman M, Motola J, Pike S, et al. (July 2021). "The iTind Temporarily Implanted Nitinol Device for the Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Secondary to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled Trial". Urology. 153: 270–276. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2020.12.022. PMID 33373708.

- ^ a b c Gilling PJ, Barber N, Bidair M, Anderson P, Sutton M, Aho T, et al. (March 2019). "Randomized Controlled Trial of Aquablation versus Transurethral Resection of the Prostate in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: One-year Outcomes". Urology. 125: 169–173. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2018.12.002. PMID 30552937.

- ^ "Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Surgical Therapy & New Technology II (MP09)". Journal of Urology. 206 (Supplement 3). September 2021. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000001982. ISSN 0022-5347.

- ^ Cho SY, Park S, Jeong MY, Ro YK, Son H (August 2012). "120W GreenLight High Performance System laser for benign prostate hyperplasia: 68 patients with 3-year follow-up and analysis of predictors of response". Urology. 80 (2): 396–401. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2012.01.063. PMID 22857762.

- ^ a b Sievert KD, Schonthaler M, Berges R, Toomey P, Drager D, Herlemann A, et al. (July 2019). "Minimally invasive prostatic urethral lift (PUL) efficacious in TURP candidates: a multicenter German evaluation after 2 years". World Journal of Urology. 37 (7): 1353–1360. doi:10.1007/s00345-018-2494-1. PMC 6620255. PMID 30283994.

- ^ a b c Sønksen J, Barber NJ, Speakman MJ, Berges R, Wetterauer U, Greene D, et al. (October 2015). "Prospective, randomized, multinational study of prostatic urethral lift versus transurethral resection of the prostate: 12-month results from the BPH6 study". European Urology. 68 (4): 643–652. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2015.04.024. PMID 25937539.

- ^ a b McVary KT, Gange SN, Gittelman MC, Goldberg KA, Patel K, Shore ND, et al. (May 2016). "Minimally Invasive Prostate Convective Water Vapor Energy Ablation: A Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled Study for the Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Secondary to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia". The Journal of Urology. 195 (5): 1529–1538. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2015.10.181. PMID 26614889.

- ^ Darson MF, Alexander EE, Schiffman ZJ, Lewitton M, Light RA, Sutton MA, et al. (21 August 2017). "Procedural techniques and multicenter postmarket experience using minimally invasive convective radiofrequency thermal therapy with Rezūm system for treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia". Research and Reports in Urology. 9: 159–168. doi:10.2147/RRU.S143679. PMC 5572953. PMID 28861405.

- ^ "Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Surgical Therapy & New Technology II (MP09)". Journal of Urology. 206 (Supplement 3). September 2021. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000001982. ISSN 0022-5347.

- ^ a b Campobasso D, Siena G, Chiodini P, Conti E, Franzoso F, Maruzzi D, et al. (June 2023). "Composite urinary and sexual outcomes after Rezum: an analysis of predictive factors from an Italian multi-centric study". Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases. 26 (2): 410–414. doi:10.1038/s41391-022-00587-6. PMID 36042295.

- ^ a b c Bilhim T, Costa NV, Torres D, Pinheiro LC, Spaepen E (September 2022). "Long-Term Outcome of Prostatic Artery Embolization for Patients with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Single-Centre Retrospective Study in 1072 Patients Over a 10-Year Period". CardioVascular and Interventional Radiology. 45 (9): 1324–1336. doi:10.1007/s00270-022-03199-8. PMID 35778579.

- ^ Pisco JM, Rio Tinto H, Campos Pinheiro L, Bilhim T, Duarte M, Fernandes L, et al. (September 2013). "Embolisation of prostatic arteries as treatment of moderate to severe lower urinary symptoms (LUTS) secondary to benign hyperplasia: results of short- and mid-term follow-up". European Radiology. 23 (9): 2561–2572. doi:10.1007/s00330-012-2714-9. hdl:10400.17/1192. PMID 23370938.

- ^ Carnevale FC, Iscaife A, Yoshinaga EM, Moreira AM, Antunes AA, Srougi M (January 2016). "Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP) Versus Original and PErFecTED Prostate Artery Embolization (PAE) Due to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH): Preliminary Results of a Single Center, Prospective, Urodynamic-Controlled Analysis". CardioVascular and Interventional Radiology. 39 (1): 44–52. doi:10.1007/s00270-015-1202-4. PMID 26506952.

- ^ a b Chughtai B, Elterman D, Shore N, Gittleman M, Motola J, Pike S, et al. (July 2021). "The iTind Temporarily Implanted Nitinol Device for the Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Secondary to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled Trial". Urology. 153: 270–276. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2020.12.022. PMID 33373708.

- ^ a b Rieken M, Ebinger Mundorff N, Bonkat G, Wyler S, Bachmann A (February 2010). "Complications of laser prostatectomy: a review of recent data". World Journal of Urology. 28 (1): 53–62. doi:10.1007/s00345-009-0504-z. PMID 20052586.

- ^ Kim A, Hak AJ, Choi WS, Paick SH, Kim HG, Park H (August 2021). "Comparison of Long-term Effect and Complications Between Holmium Laser Enucleation and Transurethral Resection of Prostate: Nations-Wide Health Insurance Study". Urology. 154: 300–307. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2021.04.019. PMID 33933503.

- ^ Al-Ansari A, Younes N, Sampige VP, Al-Rumaihi K, Ghafouri A, Gul T, et al. (September 2010). "GreenLight HPS 120-W laser vaporization versus transurethral resection of the prostate for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a randomized clinical trial with midterm follow-up". European Urology. 58 (3): 349–355. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2010.05.026. PMID 20605316.

- ^ a b Thomas JA, Tubaro A, Barber N, d'Ancona F, Muir G, Witzsch U, et al. (January 2016). "A Multicenter Randomized Noninferiority Trial Comparing GreenLight-XPS Laser Vaporization of the Prostate and Transurethral Resection of the Prostate for the Treatment of Benign Prostatic Obstruction: Two-yr Outcomes of the GOLIATH Study". European Urology. 69 (1): 94–102. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.054. PMID 26283011.

- ^ Law KW, Tholomier C, Nguyen DD, Sadri I, Couture F, Zakaria AS, et al. (December 2021). "Global Greenlight Group: largest international Greenlight experience for benign prostatic hyperplasia to assess efficacy and safety". World Journal of Urology. 39 (12): 4389–4395. doi:10.1007/s00345-021-03688-4. PMID 33837819.

- ^ Cindolo L, Ruggera L, Destefanis P, Dadone C, Ferrari G (March 2017). "Vaporize, anatomically vaporize or enucleate the prostate? The flexible use of the GreenLight laser". International Urology and Nephrology. 49 (3): 405–411. doi:10.1007/s11255-016-1494-6. PMID 28044238.

- ^ Calves J, Thoulouzan M, Perrouin-Verbe MA, Joulin V, Valeri A, Fournier G (July 2019). "Long-term Patient-reported Clinical Outcomes and Reoperation Rate after Photovaporization with the XPS-180W GreenLight Laser" (PDF). European Urology Focus. 5 (4): 676–680. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2017.10.006. PMID 29102672.

- ^ Ajib K, Mansour M, Zanaty M, Alnazari M, Hueber PA, Meskawi M, et al. (July 2018). "Photoselective vaporization of the prostate with the 180-W XPS-Greenlight laser: Five-year experience of safety, efficiency, and functional outcomes". Canadian Urological Association Journal. 12 (7): E318 – E324. doi:10.5489/cuaj.4895. PMC 6118054. PMID 29603912.

- ^ Babar M, Azhar U, Loloi J, Sayed R, Labagnara K, Zhu M, et al. (April 2023). "MP51-13 Four-Year Rezum Outcomes in Relationship to the Number of Injections: Is the "Less Is More" Treatment Approach Durable?". Journal of Urology. 209 (Supplement 4). doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003299.13. ISSN 0022-5347.

- ^ a b Roehrborn CG (August 2016). "Prostatic Urethral Lift: A Unique Minimally Invasive Surgical Treatment of Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Secondary to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia". The Urologic Clinics of North America. Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. 43 (3): 357–369. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2016.04.008. PMID 27476128.

- ^ McNicholas TA, Woo HH, Chin PT, Bolton D, Fernández Arjona M, Sievert KD, et al. (August 2013). "Minimally invasive prostatic urethral lift: surgical technique and multinational experience". European Urology. 64 (2): 292–299. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2013.01.008. PMID 23357348.

- ^ Loloi J, Wang S, Labagnara K, Plummer M, Douglass L, Watts K, et al. (May 2024). "Predictors of reoperation after transurethral resection of the prostate in a diverse, urban academic centre". Journal of Clinical Urology. 17 (3): 238–245. doi:10.1177/20514158221132102. ISSN 2051-4158.

- ^ Guo S, Müller G, Lehmann K, Talimi S, Bonkat G, Püschel H, et al. (April 2015). "The 80-W KTP GreenLight laser vaporization of the prostate versus transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP): adjusted analysis of 5-year results of a prospective non-randomized bi-center study". Lasers in Medical Science. 30 (3): 1147–1151. doi:10.1007/s10103-015-1721-x. PMID 25698433.

- ^ Kim A, Hak AJ, Choi WS, Paick SH, Kim HG, Park H (August 2021). "Comparison of Long-term Effect and Complications Between Holmium Laser Enucleation and Transurethral Resection of Prostate: Nations-Wide Health Insurance Study". Urology. 154: 300–307. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2021.04.019. PMID 33933503.

- ^ a b Ray AF, Powell J, Speakman MJ, Longford NT, DasGupta R, Bryant T, et al. (August 2018). "Efficacy and safety of prostate artery embolization for benign prostatic hyperplasia: an observational study and propensity-matched comparison with transurethral resection of the prostate (the UK-ROPE study)". BJU International. 122 (2): 270–282. doi:10.1111/bju.14249. PMID 29645352.

- ^ a b Pisco JM, Rio Tinto H, Campos Pinheiro L, Bilhim T, Duarte M, Fernandes L, et al. (September 2013). "Embolisation of prostatic arteries as treatment of moderate to severe lower urinary symptoms (LUTS) secondary to benign hyperplasia: results of short- and mid-term follow-up". European Radiology. 23 (9): 2561–2572. doi:10.1007/s00330-012-2714-9. hdl:10400.17/1192. PMID 23370938.

- ^ Knight L, Dale M, Cleves A, Pelekanou C, Morris R (September 2022). "UroLift for Treating Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A NICE Medical Technology Guidance Update". Applied Health Economics and Health Policy. 20 (5): 669–680. doi:10.1007/s40258-022-00735-y. PMC 9385790. PMID 35843995.

- ^ "Evidence | Lower urinary tract symptoms in men: management | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. 23 May 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Cacciamani GE, Cuhna F, Tafuri A, Shakir A, Cocci A, Gill K, et al. (October 2019). "Anterograde ejaculation preservation after endoscopic treatments in patients with bladder outlet obstruction: systematic review and pooled-analysis of randomized clinical trials". Minerva Urologica e Nefrologica = the Italian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 71 (5): 427–434. doi:10.23736/s0393-2249.19.03588-4. PMID 31487977.

- ^ Lokeshwar SD, Valancy D, Lima TF, Blachman-Braun R, Ramasamy R (October 2020). "A Systematic Review of Reported Ejaculatory Dysfunction in Clinical Trials Evaluating Minimally Invasive Treatment Modalities for BPH". Current Urology Reports. 21 (12): 54. doi:10.1007/s11934-020-01012-y. PMID 33104947.

- ^ Calik G, Laguna MP, Gravas S, Albayrak S, de la Rosette J (July 2021). "Preservation of antegrade ejaculation after surgical relief of benign prostatic obstruction is a valid endpoint". World Journal of Urology. 39 (7): 2277–2289. doi:10.1007/s00345-021-03682-w. PMID 33796882.

- ^ Kuntz RM, Ahyai S, Lehrich K, Fayad A (September 2004). "Transurethral holmium laser enucleation of the prostate versus transurethral electrocautery resection of the prostate: a randomized prospective trial in 200 patients". The Journal of Urology. 172 (3): 1012–1016. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000136218.11998.9e. PMID 15311026.

- ^ Capitán C, Blázquez C, Martin MD, Hernández V, de la Peña E, Llorente C (October 2011). "GreenLight HPS 120-W laser vaporization versus transurethral resection of the prostate for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia: a randomized clinical trial with 2-year follow-up". European Urology. 60 (4): 734–739. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2011.05.043. PMID 21658839.

- ^ Ghobrial FK, Shoma A, Elshal AM, Laymon M, El-Tabey N, Nabeeh A, et al. (January 2020). "A randomized trial comparing bipolar transurethral vaporization of the prostate with GreenLight laser (xps-180watt) photoselective vaporization of the prostate for treatment of small to moderate benign prostatic obstruction: outcomes after 2 years". BJU International. 125 (1): 144–152. doi:10.1111/bju.14926. PMID 31621175.

- ^ Krambeck AE, Handa SE, Lingeman JE (March 2010). "Experience with more than 1,000 holmium laser prostate enucleations for benign prostatic hyperplasia". The Journal of Urology. 183 (3): 1105–1109. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.034. PMID 20092844.

- ^ Elshal AM, Soltan M, El-Tabey NA, Laymon M, Nabeeh A (December 2020). "Randomised trial of bipolar resection vs holmium laser enucleation vs Greenlight laser vapo-enucleation of the prostate for treatment of large benign prostate obstruction: 3-years outcomes". BJU International. 126 (6): 731–738. doi:10.1111/bju.15161. PMID 32633020.

- ^ Geavlete B, Georgescu D, Multescu R, Stanescu F, Jecu M, Geavlete P (October 2011). "Bipolar plasma vaporization vs monopolar and bipolar TURP-A prospective, randomized, long-term comparison". Urology. 78 (4): 930–935. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2011.03.072. PMID 21802121.

- ^ Rai P, Srivastava A, Dhayal IR, Singh S (February 2018). "Comparison of Safety, Efficacy and Cost Effectiveness of Photoselective Vaporization with Bipolar Vaporization of Prostate in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia". Current Urology. 11 (2): 103–109. doi:10.1159/000447202. PMC 5836246. PMID 29593470.

- ^ Law KW, Tholomier C, Nguyen DD, Sadri I, Couture F, Zakaria AS, et al. (December 2021). "Global Greenlight Group: largest international Greenlight experience for benign prostatic hyperplasia to assess efficacy and safety". World Journal of Urology. 39 (12): 4389–4395. doi:10.1007/s00345-021-03688-4. PMID 33837819.

- ^ Bachmann A, Tubaro A, Barber N, d'Ancona F, Muir G, Witzsch U, et al. (May 2014). "180-W XPS GreenLight laser vaporisation versus transurethral resection of the prostate for the treatment of benign prostatic obstruction: 6-month safety and efficacy results of a European Multicentre Randomised Trial--the GOLIATH study". European Urology. 65 (5): 931–942. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2013.10.040. PMID 24331152.

- ^ Gratzke C, Barber N, Speakman MJ, Berges R, Wetterauer U, Greene D, et al. (May 2017). "Prostatic urethral lift vs transurethral resection of the prostate: 2-year results of the BPH6 prospective, multicentre, randomized study". BJU International. 119 (5): 767–775. doi:10.1111/bju.13714. PMID 27862831.

- ^ Gao YA, Huang Y, Zhang R, Yang YD, Zhang Q, Hou M, et al. (March 2014). "Benign prostatic hyperplasia: prostatic arterial embolization versus transurethral resection of the prostate--a prospective, randomized, and controlled clinical trial". Radiology. 270 (3): 920–928. doi:10.1148/radiol.13122803. PMID 24475799.

- ^ Dixon C, Cedano ER, Pacik D, Vit V, Varga G, Wagrell L, et al. (November 2015). "Efficacy and Safety of Rezūm System Water Vapor Treatment for Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Secondary to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia". Urology. 86 (5): 1042–1047. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2015.05.046. PMID 26216644.

- ^ Kaplan-Marans E, Cochran J, Wood A, Dubowitch E, Lee M, Schulman A (September 2021). "PD18-04 Urolife and Rezum: A Comparison of Device Related Adverse Events in a National Registry". Journal of Urology. 206 (Supplement 3). doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000002007.04. ISSN 0022-5347.

- ^ Pisco JM, Bilhim T, Costa NV, Torres D, Pisco J, Pinheiro LC, et al. (March 2020). "Randomised Clinical Trial of Prostatic Artery Embolisation Versus a Sham Procedure for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia". European Urology. 77 (3): 354–362. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2019.11.010. hdl:10400.17/3575. PMID 31831295.

- ^ Carnevale FC, Iscaife A, Yoshinaga EM, Moreira AM, Antunes AA, Srougi M (January 2016). "Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP) Versus Original and PErFecTED Prostate Artery Embolization (PAE) Due to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH): Preliminary Results of a Single Center, Prospective, Urodynamic-Controlled Analysis". CardioVascular and Interventional Radiology. 39 (1): 44–52. doi:10.1007/s00270-015-1202-4. PMID 26506952.

- ^ Gilling P, Barber N, Bidair M, Anderson P, Sutton M, Aho T, et al. (February 2020). "Three-year outcomes after Aquablation therapy compared to TURP: results from a blinded randomized trial" (PDF). The Canadian Journal of Urology. 27 (1) (published 2020): 10072–10079. PMID 32065861.

- ^ Desai M, Bidair M, Bhojani N, Trainer A, Arther A, Kramolowsky E, et al. (January 2019). "WATER II (80-150 mL) procedural outcomes". BJU International. 123 (1): 106–112. doi:10.1111/bju.14360. PMID 29694702.

- ^ De Los Reyes TJ, Bhojani N, Zorn KC, Elterman DS (1 September 2020). "WATER II Trial (Aquablation)". Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports. 15 (3): 225–228. doi:10.1007/s11884-020-00596-y. ISSN 1931-7220.

- ^ Porpiglia F, Fiori C, Bertolo R, Garrou D, Cattaneo G, Amparore D (August 2015). "Temporary implantable nitinol device (TIND): a novel, minimally invasive treatment for relief of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) related to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): feasibility, safety and functional results at 1 year of follow-up". BJU International. 116 (2): 278–287. doi:10.1111/bju.12982. hdl:2318/1623503. PMID 25382816.

- ^ Elterman D, Alshak MN, Martinez Diaz S, Shore N, Gittleman M, Motola J, et al. (January 2023). "An Evaluation of Sexual Function in the Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Secondary to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia in Men Treated with the Temporarily Implanted Nitinol Device". Journal of Endourology. 37 (1): 74–79. doi:10.1089/end.2022.0226. PMC 9810348. PMID 36070450.

- ^ Kadner G, Valerio M, Giannakis I, Manit A, Lumen N, Ho BS, et al. (December 2020). "Second generation of temporary implantable nitinol device (iTind) in men with LUTS: 2 year results of the MT-02-study". World Journal of Urology. 38 (12): 3235–3244. doi:10.1007/s00345-020-03140-z. PMID 32124019.

- ^ "NHS England » Decision support tool: making a decision about enlarged prostate (BPE)". www.england.nhs.uk. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Keehn A, Taylor J, Lowe FC (July 2016). "Phytotherapy for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia". Current Urology Reports. 17 (7): 53. doi:10.1007/s11934-016-0609-z. PMID 27180172. S2CID 25609876.

- ^ Bent S, Kane C, Shinohara K, Neuhaus J, Hudes ES, Goldberg H, et al. (February 2006). "Saw palmetto for benign prostatic hyperplasia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (6): 557–566. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa053085. PMID 16467543. S2CID 13815057.

- ^ Dedhia RC, McVary KT (June 2008). "Phytotherapy for lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia". The Journal of Urology. 179 (6): 2119–2125. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.094. PMID 18423748.

- ^ Franco JV, Trivisonno L, Sgarbossa NJ, Alvez GA, Fieiras C, Escobar Liquitay CM, et al. (June 2023). "Serenoa repens for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic enlargement". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (6): CD001423. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001423.pub4. PMC 10286776. PMID 37345871.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ Verhamme KM, Dieleman JP, Bleumink GS, van der Lei J, Sturkenboom MC, Artibani W, et al. (Triumph Pan European Expert Panel) (October 2002). "Incidence and prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia in primary care--the Triumph project". European Urology. 42 (4): 323–328. doi:10.1016/S0302-2838(02)00354-8. PMID 12361895.

KSF

KSF